Alfred Niger, a Black voting rights activist from Providence, may have provided the final straw that broke the back of the Dorr Rebellion. His attempt to vote in an 1841 election sanctioned by the Suffrage Association, the band of activists who perpetrated the rebellion, forced the suffragists to choose once and for all whether or not to allow Black men to vote alongside whites. Their denial of Niger at the polls set in motion their ultimate downfall.

Traditionally, the defeat of the Dorr Rebellion has been attributed to either the zealous overreach of the suffrage activists and their once-reluctant leader, Thomas Wilson Dorr, or the strength of the state’s conservative establishment. By the early 1840s, one needed to be a white man and own $134 worth of real estate in order to vote, a provision descended from the state’s 1664 royal charter, which still reigned in the absence of a state constitution. Periodically, beginning in 1811, white men left off the voter rolls and their wealthy allies petitioned the state government to relax this onerous requirement. Following the spirited national election of 1840, white male suffrage gained enough momentum to become a full-scale movement, which erupted into rebellion, brought about an illegitimate government under Dorr, and ended in disaster when the state crushed a small, Dorr-led military campaign.

One result, often mentioned as an afterthought in most of the historiography, was that Black men were given the right to vote when the state implemented a new constitution in 1843. Their re-enfranchisement was the only instance in which the vote was extended to Black men prior to the Civil War; most states, like Rhode Island, passed laws to disfranchise them in the first few decades of the nineteenth century.

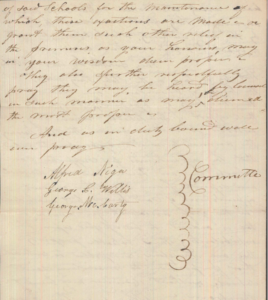

Historians have recognized that the role Black men played in defending Providence when rebels seemed poised to attack played a significant role in their enfranchisement. Only recently, however, has the literature about the Dorr Rebellion acknowledged the larger role Providence’s Black community leaders played in the overall struggle. Erik Chaput’s work, notably his book The People’s Martyr and an article he co-wrote with Russell DeSimone, has offered a more well-rounded view of the importance of race in the development of events. Black leaders, in fact, had been carefully crafting their own case for the right to vote since they were formally disfranchised by the insertion of the word “white” into the state’s voter eligibility statute in 1822. Alfred Niger was a crucial part of this movement, and this article seeks to tell his story in full for the first time.

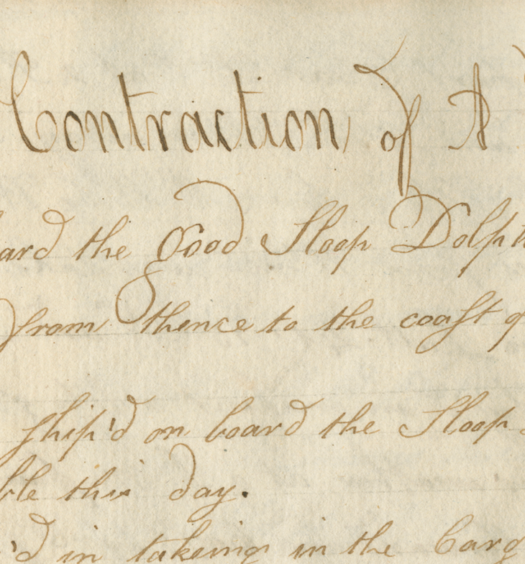

Copy of last page of the 1831 petition in which the Black community of Providence objected to being taxed without being allowed to vote or send their children to schools. The signatures are of Alfred Niger, George B. Willis and George McCarty (Rhode Island State Archives)

The Activist Barber

Alfred Niger was born, most likely in 1796, in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, one of at least four sons born to Theophilus and Submit Niger. It is unknown whether or not his parents were enslaved at the time of his birth. If his mother was, Alfred would have himself been enslaved, or at least bound to serve in a forced apprenticeship, until either his twenty-fifth or twenty-first birthday. Connecticut (at the same time as Rhode Island) had passed a gradual emancipation law in 1784 that stipulated that children born to enslaved mothers would be enslaved until their twenty-fifth birthday; a law in early 1797 reduced the term to the age of twenty-one. Little is known about his early life, but we know Alfred lived in Connecticut until at least 1808, when he, his parents, and brothers Henry, Theophilus, and William, were all baptized into the Congregational faith.

At some point between then and 1820, when he was listed as a resident Providence in the Providence Patriot, Niger moved to the town – though the circumstances that led him there are unknown. He was listed in Providence’s 1824 town directory as working as a barber on 87 High Street. Three years later, he married Julia Ann Bowen, with whom he would have at least seven children (the census and vital records are ambiguous about the precise number) before her death in 1852. His first son, born in 1832, bore the name Alexander Petion Niger, the first and middle names being the anglicized first and last names of the first president of the Republic of Haiti – signaling, undoubtedly, the pride he took in his Blackness.

The occupation he chose had a significant impact on his ascension to community leadership. In a period in which most Black northerners made their living in manual labor or service jobs, barbering as a profession offered a way to accumulate wealth and do so independently. Coupled with the fact that white clientele could offer valuable connections with city elites, their service to – and space for – the Black community helped Black barbers, through constant public contact, become visible leaders.

Niger would have come into a Black community rising in prominence despite several setbacks. In 1819, a committee of Black city leaders had come together, with the help of Quaker philanthropist and abolitionist Moses Brown, and built the African Union Meeting House. From this space, the Black community formed several of their own church denominations, opened a school, formed mutual benefit societies, and met in committees to petition the city and state. This major development, however, was clouded by, first, the state legislature’s addition of the word “white” into the state’s voting qualifications in January of 1822.

That was followed by a night of horrific violence on October 18, 1824, in which a white mob, incensed by a group of Black people refusing to yield the sidewalk to a group of white people, tore down several buildings in a largely Black neighborhood known colloquially as “Hard-Scrabble.” The Hard-Scrabble riot killed no one, but one white rioter was shot by someone defending his home. Further, one Black man who had his home torn down chose to live with the roof over his basement rather than accept the aid offered by a white women’s benevolent society, signaling a resilience that became a hallmark of Black Providence during the antebellum period.

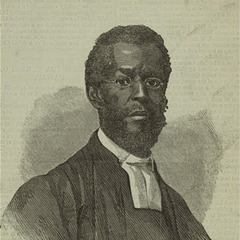

Niger’s first apparent foray into community leadership was in 1826 when he, George C. Wyllis, Ichabod Northup, and Peter Browning formed a Prince Hall (Black) Mason Lodge in Providence. Niger’s connections with Wyllis and Northup, especially, would be long-lasting and the three would help reap significant benefits for their community. Over the next few years, frustrated by disfranchisement and the Providence Town Council’s refusal to create a school for children of color as mandated by an 1828 General Assembly directive, Black leaders came up with the idea to petition the General Assembly directly. One petition submitted at the General Assembly’s fall 1829 session, whose text has not been recovered, asked for Black Rhode Islanders’ relief from taxation because they could not vote, could not educate their children in the public school system, and could not take out licenses to open certain businesses or sell liquor. It was most likely written, at least in part, by Niger; though the petition was not attributed to any writer, the fact that his effective writing ability would later become part of Black Providence’s arsenal in the fight for full Black citizenship makes his contribution a near certainty. The petition died quietly in the Assembly’s committee on finance.

On January 6, 1831, in the midst of a stormy political year (the opposition to Democratic-Republican leadership in the state seemed poised to retake control of the legislature for the first time since 1817), Black leaders convened in the African Union Meeting House and came up with their clearest strategy yet. That night, George Waterman chaired and James E. Ellis, another barber, served as secretary for a meeting called to debate the question of continued payment of taxes. Alfred Niger, along with George C. Wyllis and George McCarty, were elected to a committee tasked with drafting a petition to the state legislature laying out the resolutions of those assembled. Their petition laid out two problems: first, that Black Providence residents were subjected to taxation without a say in who could represent them. Taxation without representation called to mind the very cause the American Revolutionaries fought for; many of the Black Providence residents had fathers and grandfathers who had fought alongside white troops in the famous First Rhode Island Regiment. Secondly, Providence still refused to build a school for children of color with their tax dollars, leading to the startling situation in which Black Providence taxpayers helped pay the way for the education of exclusively white children. Niger and the drafting committee offered two potential solutions: they asked either for relief from taxation or, more preferably, continued presence on the tax rolls accompanied by the right to vote. This petition stirred some debate in the Assembly, but was ultimately not acted upon.

Perhaps it was this political action by Black leaders, coupled with the return of an elite anti-Jacksonian to power that incensed white Providence mobs to attack a largely black neighborhood for the second time in seven years. The four-night riot in the “Snow Town” neighborhood commenced nine months after the petition, in September 1831. This one culminated in the deaths of five white men at the hands of the state militia, and, a few weeks later, one Black man suspected of having shot one of the white rioters died of smallpox in jail.

Along with Providence’s Black community as a whole, Niger continued to rise. Beginning in 1830, and for six straight years, he represented Providence (alongside Wyllis and, for one year, Nathan Gilbert) as the community’s elected corresponding secretary to the Conventions of People of Color, annual meetings of Black leaders from around the North who discussed ways to improve the conditions for Black communities. In 1835, Niger and another young up-and-coming Rhode Island activist, Charles Lenox Remond from Newport, boarded with famous Pennsylvania abolitionist William Whipper for that year’s convention. Niger, Whipper, and the lesser-known Augustus Price, were appointed to draft the convention’s “address to the people of the United States, giving an exposition of the principles of our society, and the wants of our people.” Niger, Whipper, and Price laid out the case for Black men’s fitness for citizenship, vowing to promote within their communities the republican tenets of sobriety, Christianity, wealth accumulation, and education. To white Americans, they pointed out that in these facets, Black Americans already outshined whites, and on this basis, appealed for both an end to slavery and promotion to equality of citizenship. Sarcastically, they said their commitment to uplift of the human race removed any desire to subjugate whites to non-citizenship because of their lack of adherence to these republican qualities.

Niger’s activism, like those of most Black leaders in the North, was also dedicated to the most important democratic movement in the antebellum period: the movement to abolish slavery. Niger’s leadership brought him, through white abolitionist Henry Benson, into contact with William Lloyd Garrison of Boston. Garrison served as editor of the Liberator, a widely distributed abolitionist newspaper, and became arguably the second most famous abolitionist behind Frederick Douglass. By late 1831, Niger served as one of Rhode Island’s first agents of the Liberator (alongside barber James E. Ellis and Benson). His and other Black Providence leaders’ letters to Garrison and the Liberator kept the larger abolitionist community informed on their activities, especially those involving their steady campaign to win back the right to vote.

Niger was also a Providence delegate to the Garrison-led New England Anti-Slavery Society in the early 1830s, and this association led him and others to, in 1836, create the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Society (RIASS). Niger and Freewill Baptist Deacon Winsor Gardner, an African Union Meeting House stalwart, were the only Black men in attendance. From then until the end of the suffrage movement, the RIASS was to be Black Providence leaders’ most powerful ally –- likely because of Niger’s leadership within it. By its second year, 1837, Niger had ascended to the RIASS’s powerful Executive Committee. He undoubtedly had a hand in writing the committee’s resolutions that year, two of which were dedicated to prioritizing, concurrently to ending slavery in the South, the idea that all distinctions of color, which were infringements on the Declaration of Independence’s ideas about equality in mankind, should be abolished. As Niger and his cohort of Black leaders had maintained, Black residents should have the same citizenship rights as whites.

Also on the RIASS Executive Committee that year was Thomas Wilson Dorr. Over the next few years, Dorr drifted into Locofoco Democrat circles, and though he continued to champion Black citizenship rights, his abolitionism abated somewhat as the fight for getting the suffrage extended to more whites took off. The Rhode Island Suffrage Association, born in the wake of the raucous 1840 presidential election, aimed at abolishing (or reducing) the property requirements for voting. Throughout most of its existence, it’s leaders remained ambivalent to including Black leaders who, sensing potential allies, made overtures toward partnering in the fight.

In early October 1841, just before the opening session of the People’s Constitutional convention, Rev. Alexander Crummell, the young black minister of Christ Church in Providence, presented to Thomas Dorr a petition from members of the Providence black community, protesting the commitment of many of the delegates to universal white male suffrage. As an educated minister Crummell often served as the de facto scribe and spokesman for the city’s black community. The petition was signed by Ichabod Northup, Samuel Rodman, James Hazard, George Smith and Ransom Parker, all leading members of the black community.

Suffrage Association leaders said little about race until the late summer of 1841. The Association published opinion pieces both for and against the idea that their commitment to purifying the voting statute included extending the right to vote to Black men. Those in favor of including Black voices in the political process mirrored Black leaders’ arguments that the nation’s founding documents said nothing that implied equality was reserved for whites; those against inclusion fretted that including Black voting was “inexpedient,” in that Black voting would become a millstone and weigh down the movement’s soaring popularity. One pro-Black editorial presciently observed that it was an arbitrary qualification like the color line that would hamper the movement.

In the meantime, Niger and George McCarty submitted a petition to the General Assembly’s January 1841 session on behalf of a group of fifteen Black leaders. Though the text of this petition has been lost as well, according to reports of the legislative session, the petition essentially invoked the language of that of 1831: it requested either the right of suffrage or relief from taxation. This time, the Assembly called the Black leaders’ bluff, passing an act that removed Black people from the tax rolls. The May session of the legislature saw a petition drafted chiefly by two other Providence Black men, Ichabod Northup and James Hazzard (a wealthy clothes dealer), that denounced the January petition and demanded re-enrollment on the tax lists, so that in the future, their status as non-taxpayers could not be used against them in their suffrage efforts. Niger’s name is conspicuously absent from the Northup and Hazard petition’s dozens of signees, but events were moving so rapidly that it was not long before he would atone for his cohort’s January blunder.

The Mustard Seed

Though the Suffrage Association continued to rebuff Black leaders and some of its members’ calls for eschewing a color provision, its call for an election of delegates to a “People’s Convention” in October asked for “all American citizens” to vote. It did not include the word “white” before the term “citizens.” The election was to be held August 28, 1841.

Niger and RIASS allies saw an opportunity. By his attempting to vote, Niger could force the Association to confront whether it would extend Black men the right to vote. The Association would be on the record for all to see.

Niger showed up to the polling place in Providence’s Sixth Ward, where he would have been assigned to vote. At first matters looked promising. The election supervisor permitted him to vote; and other “light-skinned” people of color were apparently voting elsewhere. However, the supervisor soon overruled himself, declaring that people of color were not allowed to vote. In a move that was probably planned, Niger’s white abolitionist “friends” then declared that if Niger could not vote, then neither would they.

Niger’s action quickly wreaked havoc upon the conscience of the white suffrage movement. The event became a spectacle, resulting in one of the polling clerks resigning in protest and, over the next few weeks, unleashing a torrent of criticism directed at the Suffrage Association for its failure to adhere to the rules it set for its own election. The Suffrage Association’s president, in a reflection of his organization’s crippling inability to define its principles, warned that Niger’s action would, in maritime terms, be the “rock” on which the movement would split and sink.

At a meeting on September 24, one anti-Black member of the Suffrage Association tried, in an antic designed to make the organization’s position on race clear once and for all, to nominate Niger as its treasurer (with or without his knowledge). This “firebrand” threw the meeting into chaos, with many noting that the longer they called for “all” and not “white” citizens to participate, the more they opened themselves up to ridicule regarding the Niger incident. The president ended the meeting in short order without resolving the issue.

One Providence Journal writer, under the pseudonym “Town Born,” began chastising the Suffrage Association, warning that Alfred Niger was likely to become a “mustard seed” that would spread and overshadow the whole project. He also urged Black leaders to remain united.

Though they had been rebuffed by both the established state government and the Suffrage Association plotting a new government, Niger had moved the Black leadership team to center stage in a rapidly unfolding drama. The dramatic events continued apace.

As the Suffrage Association met in October of 1841 with the goal of writing a new state constitution, a group headed by Ichabod Northup handed a petition to Thomas Dorr, the most influential delegate to the People’s Convention. The petition remonstrated in harsh language against potential proposals to include the word “white” in the voting statute, claiming the word would be a “poisoned chalice” that would come back to haunt the Association. Dorr passionately defended the Black petitioners, but ultimately settled in favor of the majority’s will. The “People’s Constitution,” as it was called, did contain the word “white,” but promised to reconvene in a few weeks to decide other loose ends.

The legitimate state government, becoming popularly known as that of the “Landholders,” met on November 4, a few weeks after the Suffrage Association’s convention with the intention of taking up suffrage reform. To this convention, the same Black leadership team under Northup offered a much more deferential petition, asking the state government on the grounds of their historical loyalty – from when their fathers and grandfathers fought in its defense in the American Revolution through the current agitation – to abolish the color distinction in the right to vote. Dorr, one of a few men present at both the Landholders’ and People’s conventions, duly moved to strike “white” from the voting requirement, but this was quickly rejected.

Black leaders had been rebuffed by both conventions. When the subsequent winter and spring saw the Landholders and People at an impasse, however, they saw an opportunity to break the stalemate.

The abolitionist movement had been jolted awake by both the blatant rejection of Black rights and a passionate call to action from the Black-owned New York newspaper The Colored American. The National Anti-Slavery Standard lambasted defenses of the “white” provision as “the old scape-goat of Satan,” and the Liberator called out the People’s constitution “meanness, hypocrisy.”

A few days after the Landholders’ convention broke up, from November 11-13, the RIASS held its annual meeting. Alfred Niger served as one of the meeting’s Vice Presidents, and saw the fruits of his action on August 28 explode into a movement. Several of the most famous abolitionists like up-and-comer Frederick Douglass and young star Charles Lenox Remond from Newport were in attendance. One representative from the Suffrage Association who tried to explain away the “white” provision as politically expedient was shouted off the podium by William Lloyd Garrison and an unnamed Black man, and thereafter, resolution after resolution harangued both the People’s Constitution and the state government. Further, more than $1,000 was raised, much of it by Black men and women present, to sponsor a speaking tour across the state meant to urge Rhode Islanders to reject any proposed constitution – legitimate or otherwise – that included a “white” provision. Sensing they held the balance of power, the RIASS hoped a public opinion campaign focused on the color line would force either the state government or the Suffrage Association to see that the only path toward victory ran through Black voting rights.

When the People’s Convention met again later in November, the Black-led movement had some effect. A clause was added to the People’s Constitution that punted the question of Black voting. It provided that should the constitution be implemented, a referendum would be held the following year letting the white voters (including those newly enfranchised) to decide the fate of the “white” provision. Though later defended by some white abolitionists, this clause made a mockery of principle and was seen by Black leaders and the RIASS as nothing but token outreach. In December 1841, Frederick Douglass, Abby Kelley, and other abolitionists spoke at churches and auditoria around the state, often having to dodge flying eggs, snowballs, and bricks. Still, neither the Suffrage Association nor the state government budged, but the speakers at a minimum helped keep alive the fire that Niger had started in August, and made those who resisted Black voting now look like an unrepublican mob violently suppressing free speech.

In late December, the Suffrage Association held an unsanctioned election to determine whether or not its constitution should be implemented. So many white men vote that its supporters felt comfortable declaring its constitution legitimate, and the reigning state constitution and government null.

The General Assembly held its own constitutional convention in February 1842. The document it produced left intact the “white” provision. Its constitution was rejected narrowly by voters in a March referendum in which more people voted on it than the People’s Constitution. Doubtless, a RIASS Executive Committee circular reiterating its opposition to any constitution with the word “white” in it, published before the March vote, had a hand in the “Landholders’” constitution’s defeat.

The so-called “People’s Government” held an election in April in which Thomas Dorr was chosen as governor and a slate of candidates selected to fill “General Assembly” positions. The contest for legitimacy reached a climax when, in May, Dorr raised a militia force that he led in an attack on the state arsenal. When his men failed in an attempt to fire their cannon, he and his militia fled to Chepachet where they plotted their next move. The state government, now united under the banner of the “Law and Order Party” moved to more forcibly secure its legitimacy, declaring martial law in Providence in advance of a planned attack on Dorr’s forces in Chepachet in June. Concurrently with the declaration of martial law, the General Assembly announced that yet another constitutional convention would be held in September.

Drawing showing armed Dorr Rebellion supporters setting siege to the Providence Arsenal on May 17, 1841; it did not succeed (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Black Providence leaders saw victory in sight. They held meetings across the city and offered 200-400 men to help the Law and Order government capture Dorr and defend the city. Voting to eschew forming their own militia units in favor of joining white soldiers in integrated units, they were eagerly accepted. Black men also served in the campaign on Chepachet and as firefighters and peacekeepers inside city limits. Their service, like that of their fathers and grandfathers in the Revolutionary War’s First Rhode Island Regiment, was a public relations boon. The abolitionist and pro-Law and Order press published editorials praising Black Providence men for their keeping the city safe and offering their services to a government that had unduly spurned them for the past two decades.

“The Providence City Guards celebrating their Victory over the Dorrites.” Troops from Providence, including several Black men, who helped defeat the Dorr Rebels are shown enjoying a celebratory feast. From the 1841 Broadside “Governor King’s Extra” (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

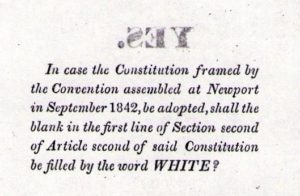

When the Law and Order constitution was drafted in September, Providence delegates especially fought for exclusion of the word “white” in the voting statute. They were only able to secure an odd blank space in the statute, with voters in a referendum deciding on, first, the implementation of the constitution itself, and secondly, whether or not the blank space should be filled with the word “white.” When it came time to vote in November 1842, the “white” provision was voted down handily, largely due to Providence voters rejecting it by a 13:1 margin. From a movement begun gingerly by Niger and his cohort of leaders in the 1820s, then accelerated by the spark he provided at the polls in August 1841, came victory – Black Rhode Island men were now voters.

Alfred Niger, however, is nowhere to be found between the November 1841 RIASS meeting and later political activism. This may be because, in June 1842, just before Black leaders joined the Law and Order cause in earnest, he lost his five-year-old son Edward to an accident involving a horse. Perhaps stricken with grief, a sentiment he must have felt acutely several more times over the next twenty years of his life (two of his daughters predeceased him in the 1850s), he temporarily removed himself from the leadership ranks. He was back, however, to partake in the strong alliance Black Providence leaders formed with the statewide Law and Order and national Whig Parties. The election cycle of 1846 found Niger and Wyllis chairing another meeting of Black leaders, this one affirming its support of the Law and Order ticket in that year’s state elections. The party, they resolved, had earned their vote by enfranchising them four years earlier, an action that they saw has having benefited their community greatly. Niger also continued his anti-slavery activism despite the decline of the RIASS, serving in 1846 as a delegate from Providence to the American Anti-Slavery Society.

An election ticket for the referendum held in 1842 to determine whether or not Black men would be allowed to vote based on the same conditions as white men (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Alfred Niger’s wife, Julia Ann Niger, died in 1852. Few Black people earned a death notice in the Providence Journal, but, perhaps out of respect for Alfred, Julia did. Two years later, he was again involved in politics, this time as part of Providence’s large interracial gathering protesting the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s allowance for the “encroachment of the slave power.” Over the next two years, however, his daughters Margaret and Mariah died at ages twenty-five and seventeen, respectively.

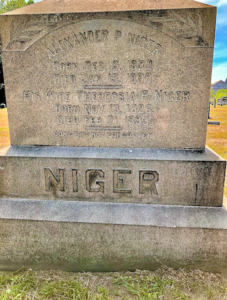

Niger’s sons followed in their father’s footsteps by becoming professionals in Providence’s Black community. Alexander became, according to one historical account of the Providence print industry, the first Black man to work in printing in the city. He probably also became the first Black member of a typographical union in Providence when he was one of its founding members in 1857. Another son, Frederick Niger, served as a print shop apprentice when the Civil War started. He died in 1863. Son Henry Niger became a barber like his father.

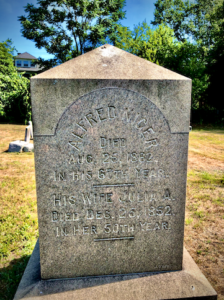

Alfred Niger died on August 25, 1862, and his funeral was held a few days later at his home on 28 Spring Street. Niger helped lead the Black community in Providence to conduct the only pre-Civil War movement in the United States to regain the right of Black men to vote, a monumental achievement that has only been given passing glances by historical scholarship. With the proliferation of histories of the abolition of slavery, of leaders in Black communities all across the country, and of the Black freedom struggle in general, the life and achievements of Alfred Niger deserve our attention.

The gravestone of Alfred Niger at Locust Grove Cemetery in the Elmwood section of Providence (the Author)

The gravestone of Alexander Niger at Locust Grove Cemetery in the Elmwood section of Providence. The son of Alfred, Alexander was a successful printer in Providence (the Author)

[Banner image: “The Providence City Guards celebrating their Victory over the Dorrites.” Troops from Providence, including several Black men, who helped defeat the Dorr Rebels are shown enjoying a celebratory feast. From the 1841 Broadside “Governor King’s Extra” (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)]

Further Reading:

For information on the history of antebellum Providence’s Black community, see Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (Cornell University Press, 1998); John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003); Robert Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Greenwood Press, 1982); Jay Caughtry (ed.), Creative Survival: The Providence Black Community in the Nineteenth Century (Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, 1984); Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York University Press, 2016); and Irving H. Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen: The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island (Urban League of Greater Providence, 1954). A valuable eyewitness account, recently reprinted with an introduction by Joanne Pope Melish, is William J. Brown’s The Life of William J. Brown of Providence R.I., With Personal Recollections of Incidents in Rhode Island (University of New Hampshire Press, 2006).

The best and most recent work on the Dorr Rebellion is Erik Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and his 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion and Chaput and Russell DeSimone, “Strange Bedfellows: The Politics of Race in Antebellum Rhode Island” in Common Place (http://commonplace.online/article/strange-bedfellows/). See also George M. Dennison, The Dorr War: Republicanism on Trial, 1831-1861 (University of Kentucky Press, 1976); Marvin Gettleman, The Dorr Rebellion: A Study in American Radicalism, 1833-1849 (Random House, 1973); and J. Stanley Lemons and Michael A. McKenna, “Re-enfranchisement of Rhode Island Negroes,” Rhode Island History, vol. 30, no. 1 (Feb. 1971), pp. 3-14.

For the political background into which the Dorr Rebellion fits, as well as a section on the rebellion itself, see Patrick Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Rhode Island Historical Society, 1977) (republished by the Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019).

All census data provided through Ancestrylibrary.com

Collection of Providence City Directories, specifically 1824, 1831, 1836, 1841, and 1844 at the Rhode Island Historical Society

Petitions listed were found at the Rhode Island State Archives except for the petition to the People’s Convention, which is found in Edmund Burke, Interference of the Executive in the Affairs of Rhode Island, 29th Congress, 1st Session, 1844, House Report No. 546

Newspapers cited here are the Providence Patriot, and Columbian Phoenix, Rhode Island American, Liberator, National Anti-Slavery Standard, Emancipator and Free American, (all of which are mostly digitized and available at the Boston Public Library’s website) and Providence Journal.