After years of obscurity, the courage and sacrifice of African-American soldiers who fought in the Civil War has been rediscovered by a new generation of Americans. The uncommon valor of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at the Battle of Fort Wagner is well known, primarily as a result of the 1989 movie Glory, which covered its formation and fighting. Although the Fifty-Fourth met with defeat at Fort Wagner, its tenacity in the battle went above and beyond the call of duty. During one of the assaults, Sergeant William H. Carney carried out a flag-saving act of bravery that eventually earned him the Medal of Honor. Many of the contemporary skeptics who publicly doubted the resolve and courage of black soldiers were silenced by the Fifty-Fourth’s performance in combat.

In an attempt to prove their worth as soldiers and to defeat the slave-holding South, both northern and southern blacks enlisted by droves in the Union army. Naturally, they also wanted to be active in securing the emancipation of slaves and ending slavery as an institution. When Colonel Thomas J. Morgan of the Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery took the opportunity to ask one of his black soldiers why he wanted to fight when he might very well lose his life, the artilleryman replied, “But my people will be free.”

All told, nearly 200,000 African-Americans enlisted in the Union army. Although the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts’ history continues to foster a sense of pride and inspiration, only a select number of other black units have been similarly heralded. During the war, black regiments participated in some thirty-five battles, but the overwhelming majority saw minimal, if any, combat. For the most part, their fighting experience was limited to occasional skirmishing. Prejudice still played an enormous part in determining their wartime roles. For the majority of blacks who enlisted during and after 1863, this meant less glamorous rear-area duty, which often consisted of garrisoning outposts throughout the Union-occupied South. Their experiences were often nothing more than a compilation of routine drudgery and daily humiliation that continued unabated until their enlistments ended or they deserted.

No better example of the black experience in the Civil War can be found than that of the Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, for the unit epitomized the average black regiment during the war. Before the war ended and because of numerous reorganizations with other black regiments, the Fourteenth carried five different titles, all sanctioned by the Secretary of War: the Fourteenth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, the Fourteenth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Corps d’Afrique, the Eighth U.S. Heavy Artillery (Colored), the Eighth U.S. Colored Artillery (Heavy), and, finally, the Eleventh U.S. Colored Artillery (Heavy).

Establishing a black unit was not unique for Rhode Island. Nearly a hundred years earlier at Portsmouth, not far from the then British-held Newport, the First Rhode Island Regiment fought bravely during the Revolutionary War in helping to repel an attack by Hessian and Loyalist troops during the Battle of Rhode Island. This regiment was the only segregated unit in the Continental Army; any slaves who enlisted were granted their freedom and their owners received compensation from the states.

In the early years of the Civil War, President Lincoln did not allow regiments of black soldiers to be established out of concern that such a move would alienate Union supporters in the border slave states. But pressure to form such regiments increased, included a letter from the Governor of Rhode Island, James Y. Smith, who requested permission to allow the state’s black men to enlist, noting that “Rhode Island has a historic right to this regiment,” as its earlier “colored regiment in the war of independence gained for itself an enduring fame.”

Finally, in June 1863, Governor Smith received permission from the War Department to form a “colored” heavy artillery company. Rhode Island was the first state to issue such a call. The response from volunteers was so overwhelming that by August the company had grown into a battalion, and by September it increased to the size of a full regiment. While Company A consisted mostly of Rhode Islanders, the remaining companies were predominantly composed of African-Americans from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and as far away as Canada (these latter men likely included some runaway slaves from the South who had escaped to Canada via the so-called underground railroad).

Colonel Nelson Viall was chosen as the commander of the newly formed regiment. Viall started his career serving as a corporal in the Mexican War during which he was severely wounded in the foot, an injury that bothered him for the rest of his life. From early in the Civil War until February 1863, Viall served with the Second Regiment Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, rising from captain to colonel, and saw action at the battles of First Bull Run (where he received a flesh wound in the hip), Malvern Hill, Second Bull Run, Chantilly, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. His selection as commander of the Fourteenth was based in part on his belief that black men, if trained properly and led by competent officers, would form capable outfits. As with most black regiments of the time, all of the Fourteenth’s field and staff officers were white men.

Camp Smith, named after Governor Smith, was established in Providence for the gunners’ initial drill and discipline. Within a few months, there were so many blacks volunteering to serve that the influx overwhelmed the recruiting depots. To train in quieter surroundings, the Fourteenth traveled to a small and obscure island in Narragansett Bay located between Jamestown and the mainland, called Dutch Island.

By December 1863, the first battalion of 400 men departed the port of Providence on board the transport steamer Cahawba, bound for Union-occupied New Orleans. Their destination was the Department of the Gulf in Louisiana. The second battalion followed in January onboard a second steamer, the Daniel Webster. Slowed by an outbreak of smallpox, the third battalion followed in April aboard the steamer, America, another commercial transport vessel. Once in Louisiana, the units were stationed at Camp Parapet, near New Orleans. For the next few months the green troops laboriously slashed down swamp grass and built fortifications. The Fourteenth Rhode Island eventually garrisoned numerous remote federal outposts, most of which were in the swamps.

Entertainment opportunities were severely limited due to construction and fatigue duties and drill, and were hampered further by the remoteness of the outposts. Yet the second battalion managed to find time to organize a string band and sing patriotic melodies. One account, published after the war, mentioned wheelbarrow and sack races and even a greased pig contest. As with other Union regiments, no doubt liquor and gambling provided additional diversions.

James Jones, a black soldier in the Fourteenth, admitted that his “face burned with shame” upon learning that only 250 of the 900 men in his regiment were functionally literate and had to mark their signatures on the payroll with an X, and yet these were men born free in New York, Ohio, “and even in the very cradle of literature and learning, Massachusetts.” During lulls in the fighting, literate black soldiers typically taught their fellow soldiers how to read and write, and soon literacy rates increased.

Within a few months the regiment had established its own semimonthly newspaper, The Black Warrior, published at Camp Parapet. Two educated black soldiers from the regiment, Sergeant Julius Hamblin and his brother George were responsible for the publication. The salutation in one of the first issues proudly proclaimed, “The paper is owned, printed, and edited by the black warriors of the Fourteenth R.I.H.A.”

The first in a series of calamities befell the regiment in July 1864 when Private James Quinn of Company A shot and mortally wounded Private Charles Cisco of the same company. Quinn was subsequently convicted of murder by a military court-martial and sentenced to death. When the sentence was carried out on November 25, 1864, Quinn was described as being utterly indifferent to his fate. Twelve men from the regiment were randomly selected as members of the firing squad and, as was the protocol, eleven of the twelve muskets were loaded with live rounds. The arms were stacked, and each squad member randomly drew his rifle. Eight soldiers in the regiment took part in the firing while four were held in reserve. According to period accounts, Quinn’s composure never faltered. He looked to and fro while acknowledging his friends. Tied to a wooden post, the doomed soldier was blindfolded while his coffin was placed directly behind him. A prayer was recited, and then the order was given: “Fire!” After being hit, Quinn’s body convulsed and slumped. Accounts at the time revealed that his death was instantaneous. Other than deaths due to illness or disease, Quinn’s was the first traumatic incident witnessed by the regiment. Ironically, Quinn died at the hands of his own compatriots. The death was a harbinger of things to come.

Weeks later, on August 5, 1864, a Confederate party boldly raided a detachment of the regiment camped at Plaquemine, Louisiana. The Union soldiers offered little, if any, resistance and the surprise attack quickly turned into an embarrassing rout. In a matter of minutes, Privates Samuel O. Jefferson, Anthony King and Samuel Mason—all from Company G—were captured. On the following day, in the nearby town of Indian Village, fifteen miles southwest of Baton Rouge, all three men were ruthlessly executed, unceremoniously becoming the only men from the regiment to be killed by Confederate soldiers.

Tragedies such as this would dishearten the most determined soldier, but another incident soon afterward seriously enraged the men. Enlistees learned that they would be paid considerably less than their white counterparts in other regiments. Several black soldiers became insubordinate when told about the difference in pay. The paltry amount offered to the black soldiers was in direct contrast to what they had been promised before their departure from Providence (while in the field, the men of the Fourteenth received $10.00 a month, $3.00 of which was allotted for clothing). One soldier warned a paymaster, “the boys will not take it.” Making matters worse, the men had seen the paymaster on only two separate occasions. The pay discrepancy was eventually rectified in their favor, not only for the Fourteenth but for all black regiments (including back-pay).

The worst adversary of all was Louisiana’s stifling climate with its insufferable living conditions. Bad water, fever, mosquitoes and poisonous snakes plagued the regiment. Indeed, duty in this godforsaken land of swamps and bayous was considered one of the most ill-fated assignments a regiment could receive. It is conceivable that the black regiment was assigned to the Louisiana swamps because white units would have rebelled against such a directive. Perhaps white commanders thought that black soldiers could more readily adapt to this harsh environment. On the surface it appeared that both the officers and enlistees of the Fourteenth were considered expendable by their own government.

With minimal health care available for the welfare of white regiments at the time, struggling black regiments in the field received even fewer medical supplies. Shortly after the men’s arrival in Louisiana, numerous illnesses and diseases began to run rampant throughout the camp. Malaria, dysentery, measles, swamp fever, smallpox, typhoid fever, and consumption took a deadly toll. Men of the Fourteenth died in appalling and agonizing ways, and Surgeon Benoni Carpenter and his assistants could do little to curb the suffering.

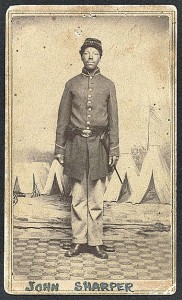

Private John Sharper, of the Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) hailed from Providence and was mustered out with a surgeon’s certificate on September 11, 1865. Source: Library of Congress

During the war nearly one in every ten whites died of disease. Within black regiments the death rate was double. The reason for such a discrepancy is not clear. There could be several possible explanations, but perhaps it was simply because black regiments served in harsher environments for longer periods than did their white counterparts. But in the final analysis, though the death rate was significantly higher for black enlistees, diseases and ailments also took their toll on white officers. Before being reassigned to the regiment, Captain A. Richmond Rawson of Providence served twenty-seven months in a southern climate and was exposed to the damp trenches at Fort Wagner. After less than a week with the Fourteenth, he was sent home, sick with chills and fever. Rawson lingered for another four months before dying on May 5, 1864.

For those who managed to survive the dreadful climate, depression took its toll. Considering the gloomy conditions and the distinct possibility of contracting a life-threatening illness, desertion became an attractive option for some of the men. Yet, surprisingly, the rate was only half that of other Union regiments during the war. Of the total enlistment in the Fourteenth, desertions accounted for only four percent of the original roll. The black soldiers were a determined lot in spite of all the hardships.

Within Company D alone, more than thirty-one percent of the men either died or became disabled. Out of the entire regiment, 438 men eventually succumbed or were discharged as invalids on surgeons’ certificates. Including eighty deserters, twenty-eight percent were no longer counted as part of the regiment’s final strength at war’s end. In addition to those who died from disease or deserted, two soldiers were accidentally killed by gunshots, one was slain while assaulting an officer, one was sentenced to hard labor in a Florida prison for mutiny, and another committed suicide.

On October 2, 1865, with their services no longer required, the men of the Fourteenth mustered out of service and proceeded to Providence aboard the steamer North Star. En route, the regiment stopped in New York City, where they marched up Broadway to cheers from large and appreciative crowds. The regiment then boarded the propeller-driven vessel Doris, which transported them to their final destination. Not long after the boat arrived on October 21 at the docks in Providence, the local citizens celebrated the regiment’s return with yet another parade. Newspaper accounts at the time reported that the soldiers marched to the beat of a band playing the popular tune, “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!” while accepting the applause and well wishes of hundreds of native Rhode Islanders—black and white citizens alike.

The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, as with many other black regiments in the war, did not receive their fair share of the credit. The high price paid in death and suffering, even if mostly by disease, became the regiment’s marked contribution to the preservation of the Union.

Shortly after the war ended, Rhode Island’s acting adjutant general, Colonel H. Crandall, summarized the contributions and sacrifices made by the regiment in brief, yet eloquent terms when he wrote: “Their work was laborious and often disagreeable without the inspiration of glory, and was always patiently and faithfully performed. For this, impartial history will reward just praise.”

Suggested Reading:

Two main sources were used to compile this article. The reader may wish to peruse the Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Rhode Island, for the Year 1865, compiled by the Adjutant General of Rhode Island. Some of the larger libraries within the state have the volume in its reference section. A copy is also available for in-house research at the Rhode Island State Archives on Westminster Street in Providence. The large volume was published in 1866 by the Providence Press Company (printers to the state). Pages 625 through 679 includes both a history of the regiment and company rosters that list names, residence, and date of muster, along with brief remarks highlighting muster information and deaths while in service. A more detailed accounting of the regiment can be found in the unit’s regimental history: The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865, by William H. Chenery, and originally published by Snow & Farnham of Providence in 1898. This book can be found in reference sections at most public libraries in the state. In recent years, the book has also been reprinted and can be purchased online. This article has also relied on Douglas R. Egerton’s The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era (Bloomsbury Press, 2014), which has an excellent discussion of black regiments in the Civil War.

Since 2002, over 300 Providence teens have participated in Living History programs. In 2009, Living History launched the Career Institute in History and Preservation. The Institute provides students with training in historic interpretation, acting, preservation planning, and preservation trades. Internships with Rhode Island history and preservation organizations are arranged for all students. One of the living history programs that the Institute sponsors is a student reenactment of the Fourteenth Rhode Island Regiment Heavy Artillery (Colored). The organization has a Facebook site. To learn more visit: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Living-History-14th-RI-Regiment-Heavy-Artillery-colored/148141653172.