In 1824, several months after he graduated from Harvard College, Thomas Wilson Dorr (1805-1854), the son of a prominent Providence, Rhode Island merchant, entered into a philosophical debate with his younger brother Allen (1808-1889). The Dorr brothers debated whether a crime committed for the greater good of the citizenry was justifiable. Allen was in his final year of study at Phillips Exeter Academy, his brother’s alma mater. Allen wanted to debate the question with the members of the Golden Branch Literary Society. Six years earlier, Thomas, then in his second year at Exeter, helped to found the secret society. Allen was inducted into the Golden Branch in 1822. A person “might indeed be arraigned and perhaps condemned before a civil tribunal” for trying to “enforce the will of his Creator,” wrote Allen, but he would not “suffer” for “any crime morally imputable to him.” Twenty years later, Thomas received a unique opportunity to put this theory to the test.

In the spring of 1842, Thomas Dorr led an armed rebellion to change Rhode Island’s archaic form of government. His goal was to implement the People’s Constitution, a document that he believed had been ratified by the majority of white male voters in an extralegal plebiscite held in late December 1841. The stringent property qualifications for voting, which stemmed from the state’s continued use of the 1663 colonial charter, were removed in the People’s Constitution. The sitting legislative assembly, however, never authorized nor accepted the vote on this constitution.

For Thomas Dorr, the signing of the 1776 Declaration of Independence meant that the right to revolution was “an inherent right in the people, which they could at all times peacefully exercise.” The Jeffersonian right of revolution, the right to make the world new again, was one of Dorr’s bedrock moral principles. As Allen perceptively noted in 1823, the “course of conduct which a person pursues may be considered the result of his strongest passion or principle.” Thomas’s opponents were equally as passionate. Dorr’s two other brothers, Sullivan, Jr., and Henry, both condemned his actions in the spring of 1842. William P. Blodgett of Providence, Allen’s closest friend while a student at Exeter, belonged to a militia unit that hunted Thomas in late June 1842.

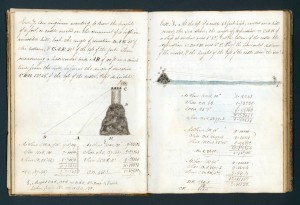

A notebook from a student who attended Phillips Exeter Academy around the time the Dorr brothers did (Courtesy of Phillips Exeter Academy)

The problem that Thomas Dorr faced in 1842, was that the “civil tribunal” that Allen talked about two decades before had not only condemned him but also went to great lengths to capture and kill him. Dorr’s parents, Sullivan and Lydia Allen, had always hoped that their oldest son would use his considerable education to do great things. In the 1830s, it seemed that Dorr was embarking on a legal career that would rival his hero and fellow Exeter alumnus Daniel Webster. Thomas’s parents surely did not envision that their oldest son’s name would ever be connected with a rebellion. In 1842, Sullivan and Lydia were likely reminded of Allen’s urgings in the 1820s that his older brother should join the priesthood. Now the majority of the Protestant clergy in Providence wanted to see his “head on a pike” as one clergyman put it.

In the seven years I spent researching the life of Thomas Wilson Dorr, I always knew that his time at Phillips Exeter Academy was vitally important. “I have the pleasure to state to you that your son … is a Youth of promising character and scholarship and highly worthy of my commendation,” wrote Hosea Hildreth, a beloved teacher at the Academy to Sullivan Dorr in December 1818. After graduating from the Latin Grammar School in Providence in 1817, Thomas spent two years at Exeter, an institution that was well-known within the extended Dorr family. Many of the children of Sullivan Dorr’s brothers in Boston attended the Academy. Dorr’s uncles Zachariah and Crawford Allen, prominent textile manufactures, also benefited from their time at Exeter.

The liberal arts education the Dorr brothers received at Exeter provided them with the genteel qualities required to become societal leaders. In 1838, Thomas wrote a moving tribute for Benjamin Abbott, the “venerable preceptor” during his time at Exeter. The Academy was honoring Abbott for a half-century of service. The “important, useful, and liberal profession of the teacher of the young” ensured the success of “republican government,” according to Thomas. At Exeter, Thomas learned what “republican government” meant and what it meant to break free from prejudices and parochialism and to make disinterested judgments for the common good.

After the completion of his first year, Principal Abbot recommended to Sullivan Dorr that Thomas spend an extra year in order to better prepare for the “higher” standard of “excellence” at Harvard. “I cannot, my dear Sir, close this hasty letter without congratulating you on the prospect of having your son to gratify all the reasonable wishes of a fond parent.” From Canton, China Dorr’s merchant uncle Samuel reminded him that the “foundation laid” at Exeter would help him to succeed at Harvard.

In the massive correspondence files (over 2,000 items) at the John Hay Library in Providence there are over twenty letters from Allen Dorr to his older brother. These letters shed light on the early history of Exeter and Harvard. In the 1820s, the tuition at Exeter was in the range of $12 per year. Since there were no dormitories, the Dorr brothers lodged with town residents. Evidence suggests that Thomas and Allen spent time in the home of former governor John Taylor Gilman. Allen often referred to life at the Academy as “tranquil.” He loved the snow and was thrilled when he could go sledding and ice-skating with his friends. Allen wrote frequently to Thomas asking him to send him books and pose questions that he could debate.

In Cambridge, Thomas was tutored by Exeter alumnus George Bancroft. Dorr later encourage his younger brother Sullivan to attend Bancroft’s Round Hill School in western Massachusetts. John Paul Robinson, Dorr’s classmate at Exeter, would later be at the center of a “rebellion” at Harvard in 1823 that led to the expulsion of half of the class. In November 1822, Allen was happy to report to Thomas that the “Academy” was “in a very flourishing state,” free from the seemingly constant turmoil in Cambridge. There were “as many large scholars as ever” at Exeter and “I believe more attention is generally paid to study than heretofore,” wrote Allen.

This is not to say that the Exeter students did not behave like teenagers. In one letter Allen reported that three students met up with some “young town men” and after “getting high,” presumably a reference to drinking, “broke down the grave-yard fence and broke open several doors.” After their antics at the Winter Street cemetery, the boys then proceeded to assault a man on the street, “demanding his money.” After being “scolded” by the preceptor, the boys “cleared off” and went to Boston “with an intent to go to sea.”

At the time of the Dorr brothers attendance, the curriculum at Exeter was divided into two departments or tracks—English and College Preparatory. Thomas was slotted into the College Preparatory track. Allen was on the English track. His letters indicate that he took courses in geometry, logic, economics, science, and history. Allen spent many hours reading the recent works of English philosophers William Paley and Thomas Brown. Allen and Thomas both studied Roman history, particularly the lives of Cicero and Cato. The “hopes and wishes of both men were concentrated in one grand point—the public good,” wrote Allen to Thomas as he prepared to serve as a judge during an upcoming exhibition. Allen also debated the characters of Napoleon Bonaparte and George Washington.

Exeter’s curriculum instilled in Thomas Dorr a belief that he could rise above the political fray and competing party interests to discern the interests of the common good. Though they grew up in a lavish mansion on Benefit Street in Providence, the Dorr brothers frequently railed against what Allen called the “domination of the rich.” Thomas conceived of his actions in 1841-1842 as a way to curtail the influence of the “money-power.” He wanted to drive the money changers from the temple. However, when it was over, the money changers drove him right out of the state.

Thomas lived in exile in New Hampshire for over a year. He returned to Providence in late 1843. In June 1844, he was condemned by Rhode Island’s highest court for committing treason against the state. Though he wallowed in prison for a year, Thomas never wavered in his belief that he was morally right. As he sat alone in his dark, damp cell in the new state prison on Providence’s cove, his correspondence with his younger brother from twenty years before was likely never far from his mind.

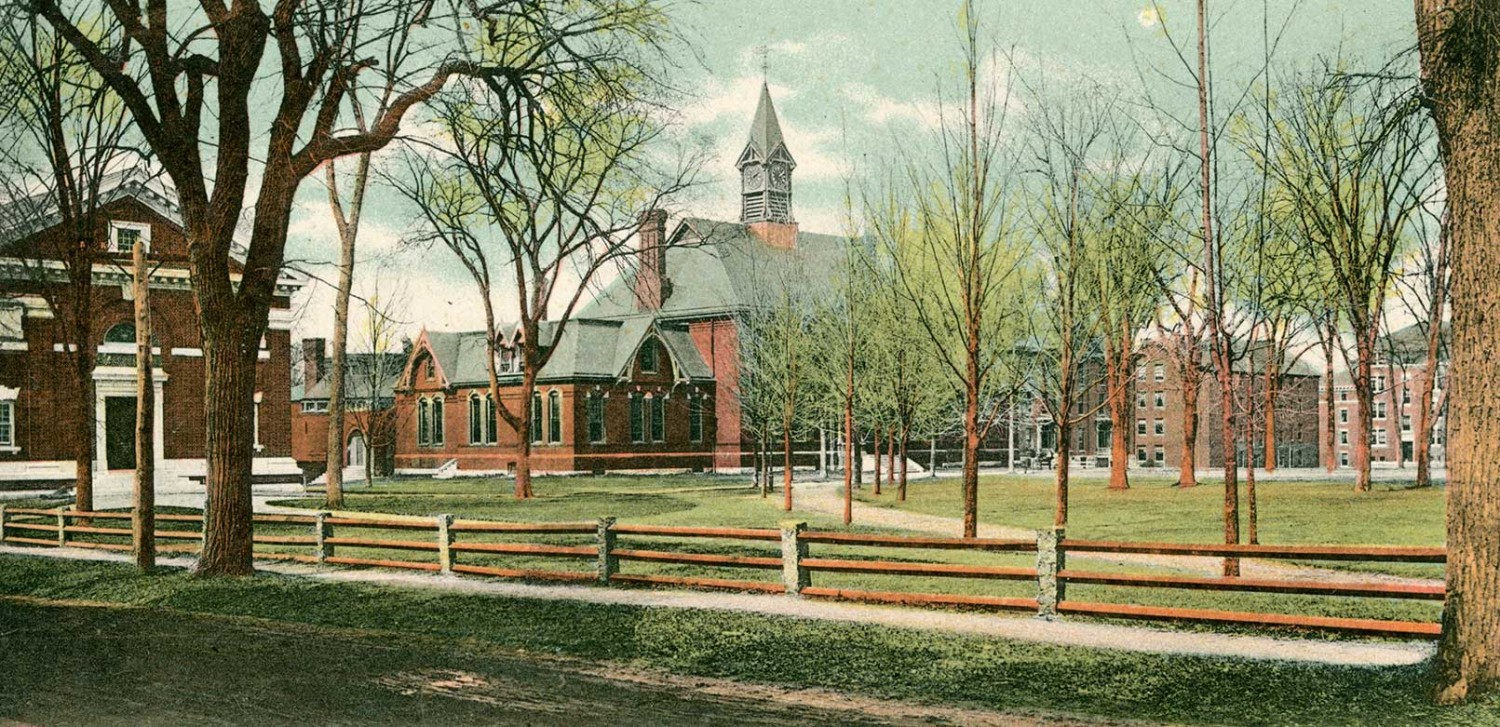

(Banner image: The Phillips Exeter Academy and buildings, circa 1903 (Courtesy of Phillips Exeter Academy)

Suggested Reading:

For more on the life of Thomas Wilson Dorr and the 1842 rebellion that bears his name see Erik J. Chaput, The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (University Press of Kansas, 2013). For a discussion of the literature on the Dorr Rebellion see Chaput, “The Rhode Island Question: The Career of a Debate,” Rhode Island History 68:2 (Summer/Fall, 2010): 46-75. See also Patrick T. Conley, Democracy in Decline: Rhode Island’s Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Rhode Island Historical Society, 1977). The Thomas Dorr-Allen Dorr correspondence can be found in Box 1 of the massive Rider-Dorr Correspondence Collection at the John Hay Library in Providence. See also the Rider Papers and the Thomas Wilson Dorr Papers at the John Hay Library (separate collections). Several interesting letters from Dorr’s early years have been annotated and digitized and on the Dorr Rebellion Project Website: http://library.providence.edu:8080/xtf/search?browse-all=yes