Rhode Island is fortunate to still have five working grist mills, four of which are open to the public. One of them stone grinds, produces and sells johnnycake meal as a business—Kenyon’s Grist Mill in charming Usquepaug in South Kingstown. (Note that the photographs from 1940 discussed below are at the end of the article, in the order of the grist milling process).

From the seventeenth century to the early part of the twentieth century, grist mills dotted Rhode Island’s rural landscape. Grist mills were crucial for farmers to turn their wheat and corn into flour and corn meal. Corn meal in particular became an item of export and remained so into the twentieth century. Corn meal was used in breads (often mixed with rye) and in the characteristic southern Rhode Island specialty, johnnycakes, a pancake made of corn meal and water or milk, usually cooked on a griddle.

Today, most grist mills grind native grown corn to make corn meal. The following description of milling is from the website for Gray’s Grist Mill in Adamsville, Rhode Island. After husked corn is dried for six to eight months, it is then shelled and bagged for milling. The dried corn is poured out of the bag into the hopper, which is located above the grinding stones. A vertical rod, called the damsel, is used to shake the kernels downward, through the “shoe” and into the millstone. The hopper at Gray’s Grist Mill releases an average of three bushels of corn an hour for grinding.

Paul Drum explaining how his grist mill works, October 2016 (Margaret McBurney)

Paul Drum explaining how his grist mill works, October 2016 (Margaret McBurney)

The huge millstones that grind the corn are what really make grist mills amazing. Some of them date back to the eighteenth century. Many came from Europe, some as ballast in ships. The two millstones at Gray’s Mill each are fifteen inches thick and weigh one and one-half tons. The 56-inch granite stone is used for grinding corn.

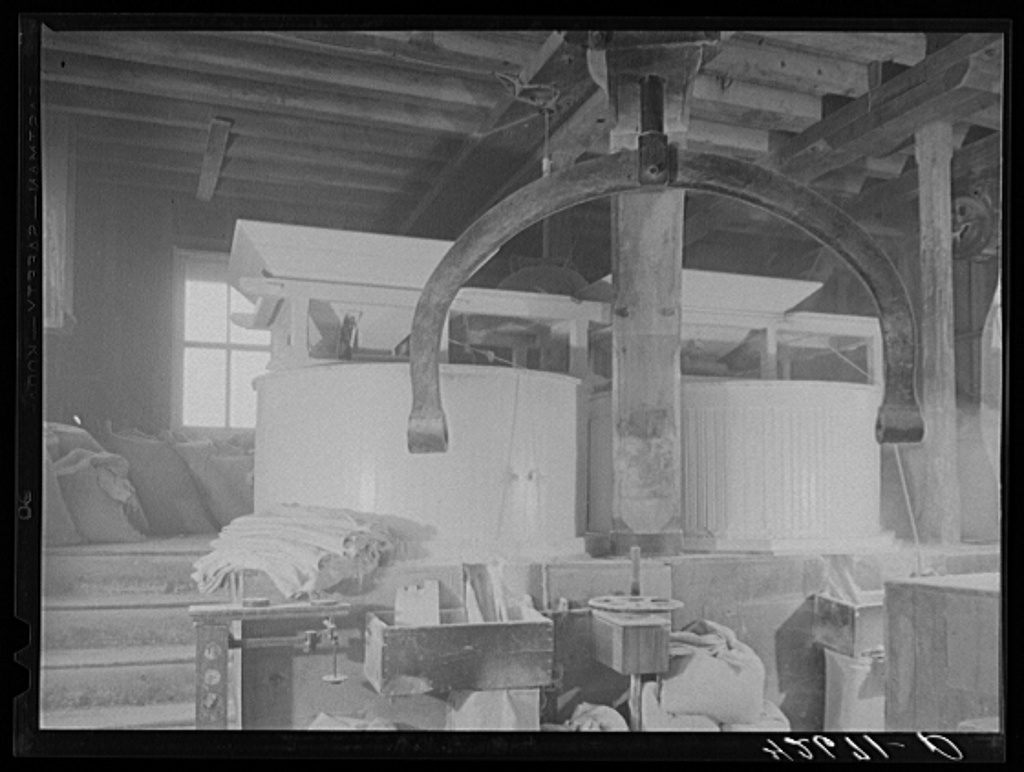

“The grinding surface of these ‘runner’ stones, or top stones, is concave and carved into spoke patterns. The runner stone sits atop another ‘bed stone’ or ‘nether stone,” which is also carved. As the top stone rotates, the grain first gets cracked in the middle of the two stones, then is pushed to the outside by the spoke-like pattern. The finest grinding occurs along the perimeter. When the millstones need to be cleaned ,sharpened or repaired, the runner stone is lifted with a stone crane, using a hand screw jack.”

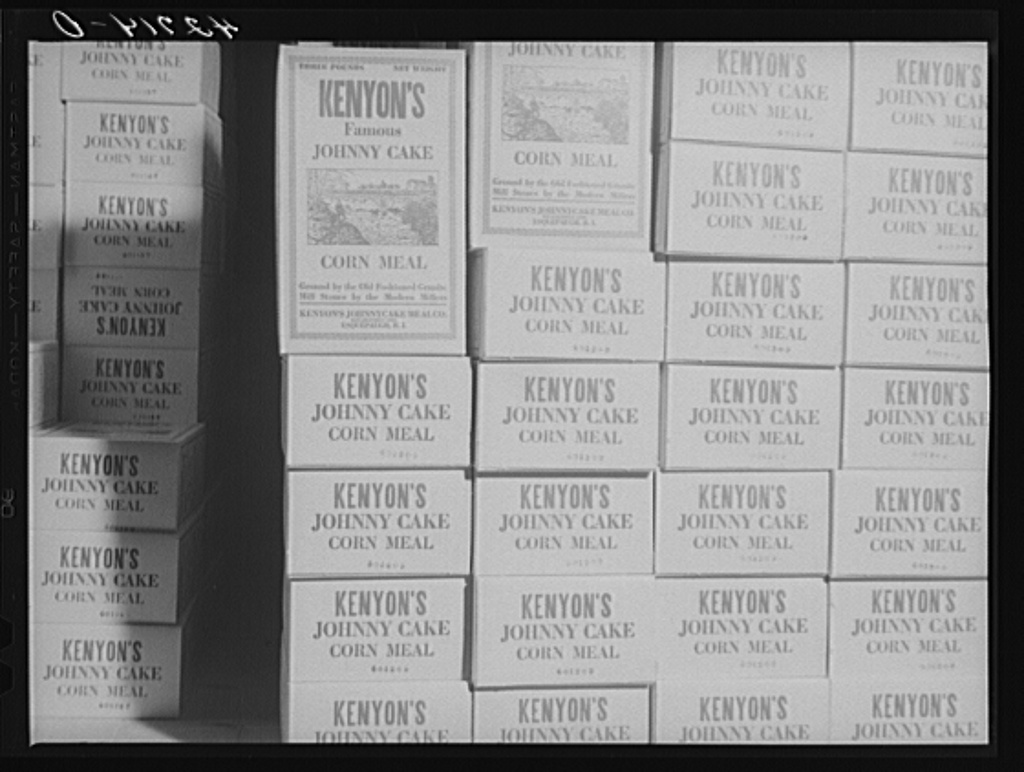

The Kenyon’s Grist Mill’s website proclaims that the huge millstones “produce the exceptional texture and quality not found in modern, steel ground flours. Single pass stone grinding also preserves the vital, natural nutrition of the grains.” While some mass market boxes of flour advertise its flour was grilled by millstones, many times the flour also is milled using steel, which results in the flour losing much of its nutrients.

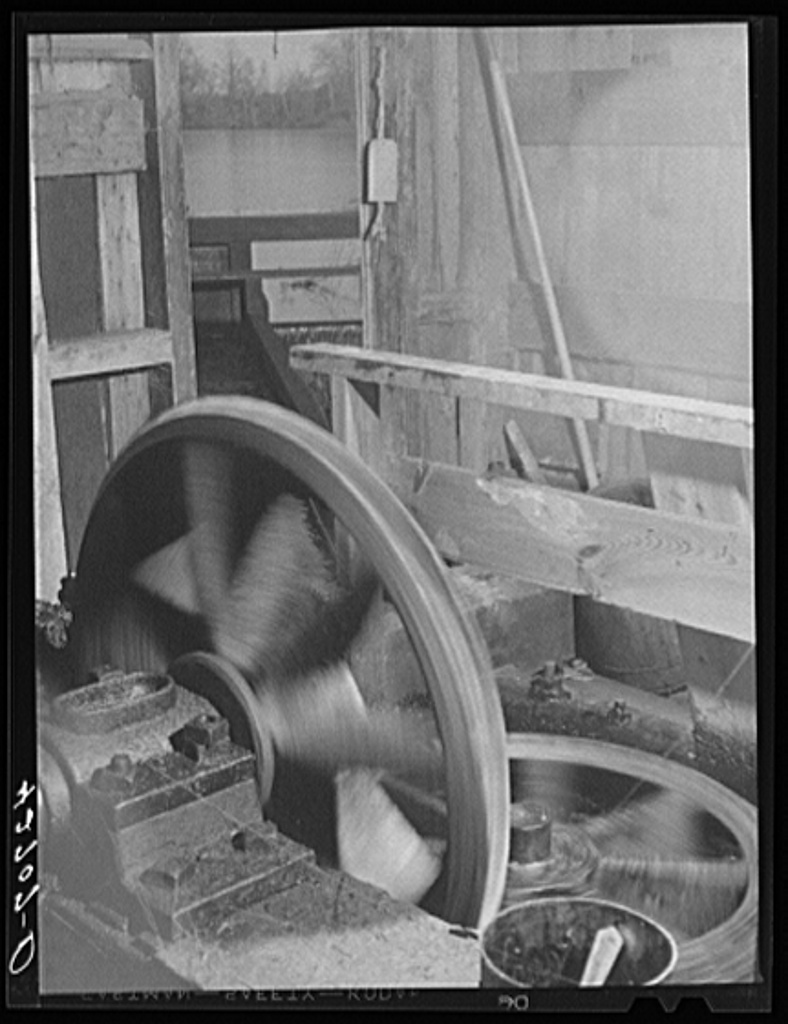

Traditionally, grist mills operated by waterpower. Mills needed a steady, but not rushing, current of water. A sluice gate would be opened starting a steady flow of water, causing a water wheel to turn, this providing power to grind the corn. Today, some grist mills are electric powered.

Kenyon’s Grist Mill is located in the charming village of Usquepaug, nestled on the banks of the Queen’s River, on the South Kingstown-Richmond boundary line. Usquepaug is located on Route 138, in between the exit off Route 95 and Kingston village. It used to have a tavern, post office, general store, cider mill, and cotton mill, but now it just has Kenyon’s Grist Mill and a small collection of picturesque nineteenth century houses.

Kenyon’s Grist Mill’s colorful current owner, Paul Drumm III, informed me that a representative of the Rhode Island Historical Society showed him a historic map indicating that a grist mill had been located on Queen’s River near Kenyon’s Grist Mill since 1696. My own research indicates one was located there by 1700 and was called Cottrell’s Mills. In 1716 it was taken over by Peleg Mumford, and the village for more than a century became known as Mumford’s Mills. The foundation of the former mill can be seen today just south of the current Usquepaug Bridge spanning Queen’s River.

The current two-story, clapboard Kenyon Grist Mill was built in 1886. In 1909 Charles Kenyon bought the mill and began grinding jonnycake meal from local Narragansett white-cap flint corn. Kenyon added in 1909 two new sets of mill stones, one from the Westerly Granite Company (one of them has markings indicating it may date back to the eighteenth century). He began to produce jonnycake meal in sacks with the Kenyon name on it and distribute then to retailers around the state. The sacks were transported as far away as Providence by horse and buggy. In 1916, the company bought a Model T truck, allowing distribution of johnnycake meal to extent into parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts.

In December 1940, Jack Delano rolled up in his automobile, probably a Model T, next to Kenyon’s Grist Mill, then called Kenyon Grist Mill. Delano was one of a handful of photographers hired by the Farm Security Administration during the Depression Years to photograph different parts of the United States. Delano, born Jacob Ovcharov in 1914 in Ukraine, and his family fled persecution to the United States in 1923. He came to the attention of the Farm Security Administration after publishing striking images of ordinary coal miners in Appalachia. He obtained a coveted job as a photographer in 1940 when jobs were difficult to come by. He would not become as famous as other Farm Security Administration photographers hired during the Depression years, such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, but Delano left an impressive legacy, now held by the Library of Congress.

Delano visited Kenyon’s Grist Mill as part of his six-month tour of rural New England. He was seeking close-ups of people and activities in small towns and villages. In many respects, it is a world now lost. Glimmers of it can still be seen at Kenyon’s Grist Mill, where Delano took a series of about eighteen photographs.

Delano’s photographs, most of them reproduced at the end of this article, show the process of milling and boxing corn meal from beginning to end. Many of the photographs are striking. “To do justice to the subject has always been my main concern,” Delano wrote in his autobiography. “Light, color, texture and so on are, to me, important only as they contribute to the honest portrayal of what is in front of the camera, not as ends in themselves.”

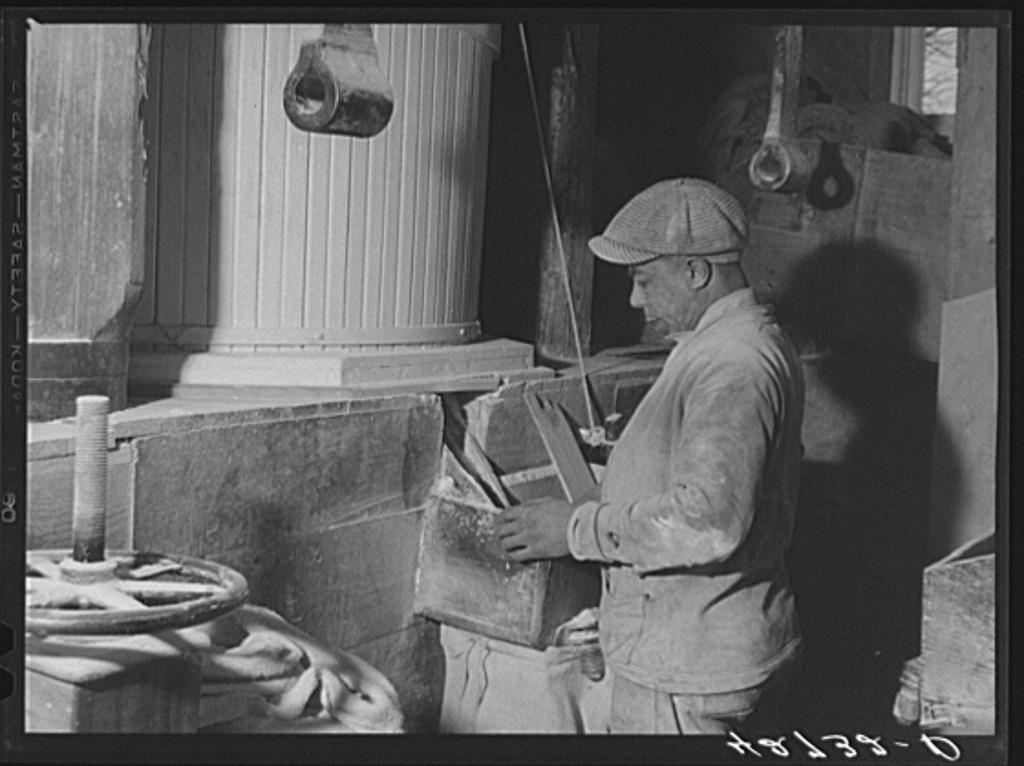

Charlie Wamsley, with Narragansett Indian and African-American heritage, appears in three of Delano’s photographs. Charlie’s father worked at Kenyon’s Grist Mill for about fifty years. In 1914, when Charlie was just ten years old, his father removed him from school and he was put to work at Kenyon’s Grist Mill. Amazingly, Charlie worked there for some seventy years.

Today Kenyon’s Grist Mill is electric powered. The race is overgrown now and Queen’s River no longer generates power. Just around the corner from the mill is a small, but still impressive, waterfall.

Paul Drumm II purchased the mill in 1971, and his son, Paul Drumm III, continues the tradition. Karen Ellsworth of Matunuck recalls that when she was just starting out as a reporter for the Providence Journal, “I was sent to cover the annual fall festival at Kenyon’s. Charlie Walmsley was working there, and I remember talking to him. Paul Drum’s father, Paul Drum II, operated the mill back then. We were standing next to the mill watching tourists pour maple syrup on their jonnycakes and I mentioned to Paul that my grandfather would make steak and jonnycakes for supper in Sunday nights, and we ate them with butter and salt, not maple syrup. I knew that as a miller of corn meal, he probably would know that jonnycakes traditionally were served as a side dish, like potatoes, not as a breakfast food. I was right—such a look of wonder and gratitude came over Paul’s face that I thought he was going to cry.”

Kenyon’s Grist Mill sells virtually year-round jonnycake meal, Paul’s clam cake and fritter mix, and other local products in a small shop across the street. The boxes of jonny-cake corn meal look much like they do in Delano’s 1940 photographs. Once or twice a year Paul will give free tours of the mill and the grinding process, and visitors can sample free johnnycakes.

In addition, visitors in the spring, summer and fall can enjoy some outstanding kayaking on the Queen’s River, with a trip ending under Dugway Bridge and in a remote Audubon nature preserve. Kenyon’s Grist Mill can provide all the equipment.

Visitors to Kenyon Mill would find worthwhile a short ride up Glenn Rock Road to a former grist mill and sawmill called Glen Rock Mill. The current stone building was likely constructed in the first half of the nineteenth century as a grist mill or sawmill; it stands immediately next to a small but still rushing waterfall. Today the building is used by Peter Pots Pottery to sell its renowned handcrafted pottery.

The other grist mills in Rhode Island open to the public are: the Perry-Carpenter Grist Mill at 364 Moonstone Beach Road in South Kingstown; the Hammond Gristmill at the Gilbert Stuart Birthplace & Museum in North Kingstown; Gray’s Grist Mill in Adamsville, Rhode Island in Tiverton straddling the border with Massachusetts; the Jamestown Wind Mill; and Boyd’s Wind Grist Mill in Portsmouth. They are so fascinating, they deserve their own articles. Interestingly, the surviving grist mills are all in the southern part of the state. The grist mills in the northern part of the state were typically converted into cotton or wool mills.

[Banner image: Kenyon’s Grist Mill in 2017; it has not changed much in 141 years (Author)]

Kenyon Grist Mill in Usquepaug, from the east, showing waterfall on right, Dec. 1940 (Library of Congress)

Kenyon Grist Mill in Usquepaug, from the east, showing waterfall on right, Dec. 1940 (Library of Congress)

Bins for storage of corn and corn meal. Similar buildings still exist, though now they are residences (Library of Congress)

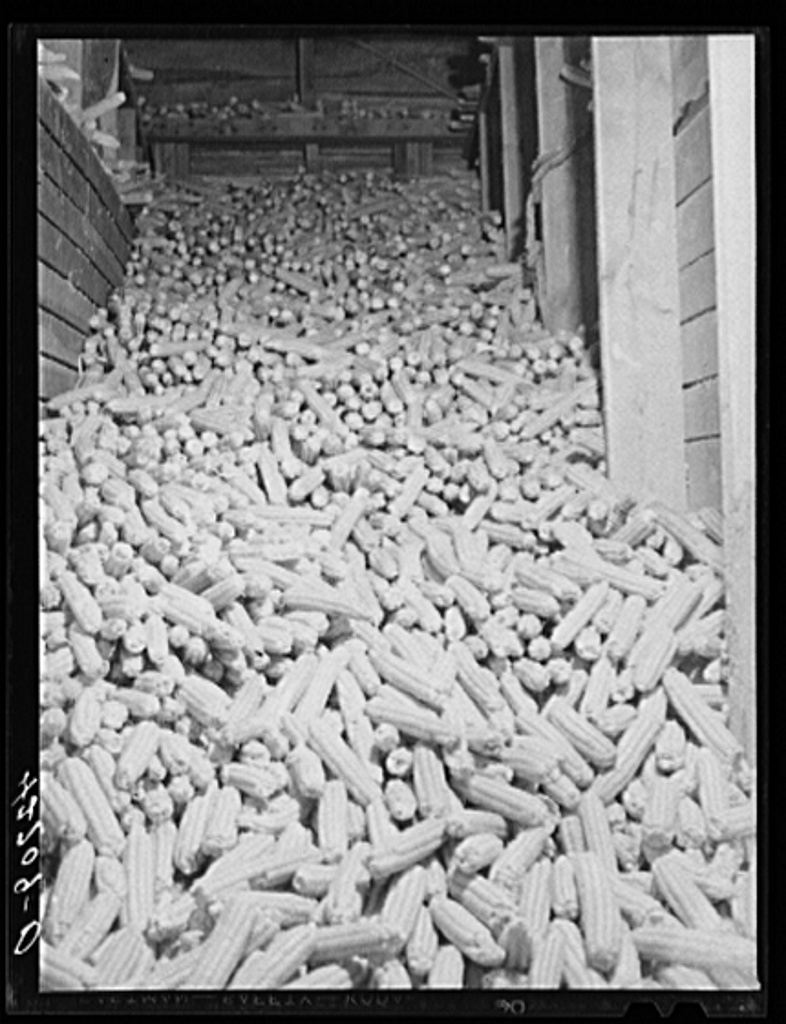

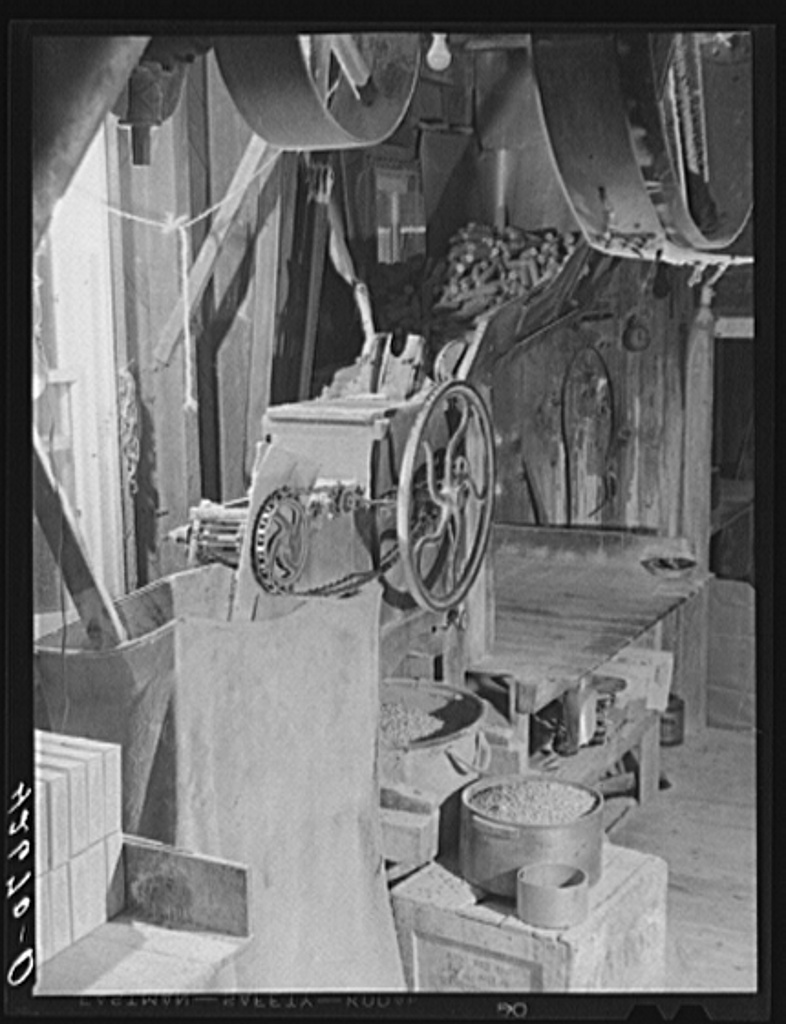

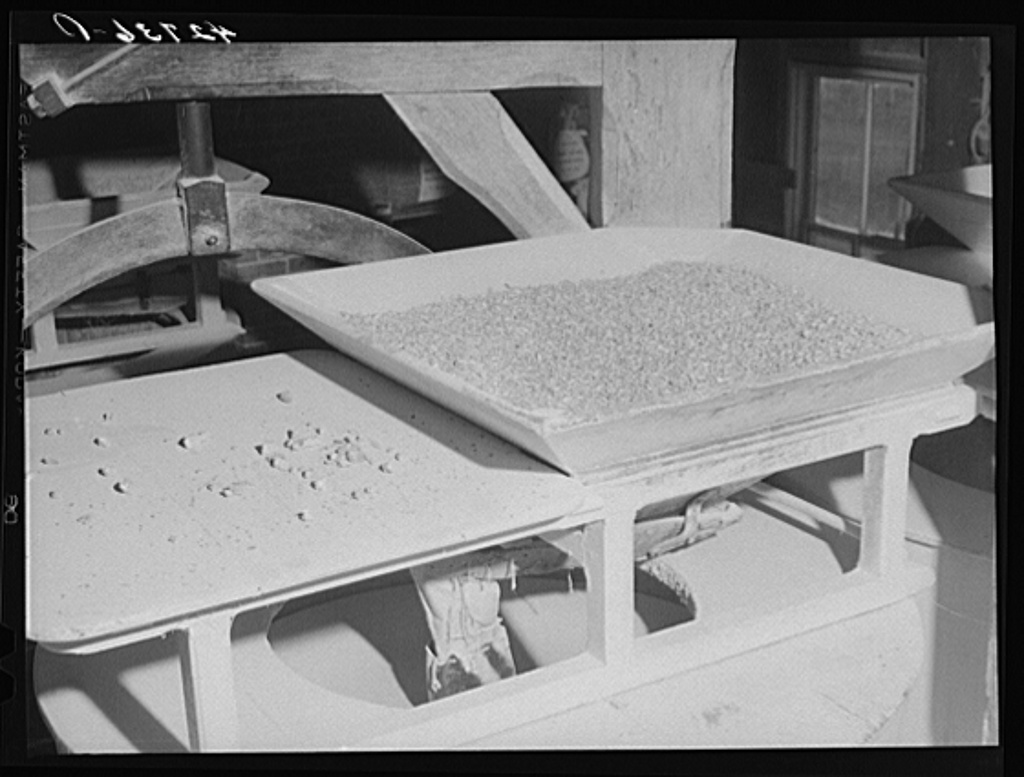

The first step in the process of making johnnycake flour is removing the corn from the cob, Dec. 1940 (Library of Congress)

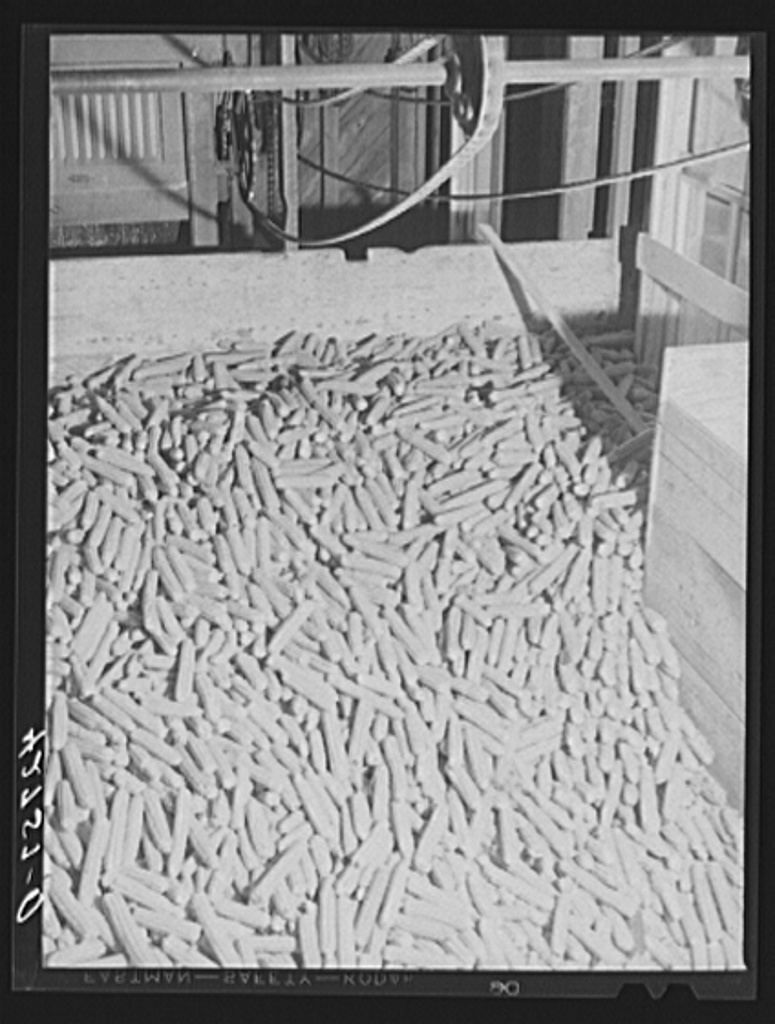

A hopper sitting over the grind stone feeds corn into the grind stones, Dec. 1940 (Library of Congress)

Inside the two white round bins are ancient grind stones used to grind the corn into corn meal. The curved iron arm is used for lifting the heavy stones out for cleaning, Dec. 1940 (Library of Congress)