Whaling “is a wretched life [of] privations and hardship deprived of friends and society,” John Scott Deblois (1816-1885) wrote in an 1844 letter to his family in Newport. [1] Voyages during the age of sail were long and whaling voyages were markedly longer. Living aboard a 19th century whaling ship was a life of deprivation, yet it must have had a strong hold on whaling ship master Captain Deblois for he spent more than half of his life at sea. Deblois’s adventures are recorded in the surviving log books, journals and letters in the Newport Historical Society’s manuscript collection in the John S. Deblois papers. These documents provide insight into the allure that may have captivated Deblois and others who followed the same path, while illustrating what life was like for this notable 19th century Newporter.

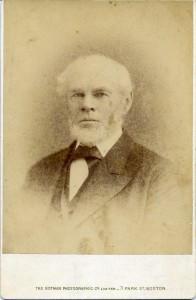

Born to John and Sarah Scott Deblois in Newport, R.I., on November 25, 1816, John S. Deblois was the oldest of eight children. He began sailing as a young boy and served as the third mate aboard the whaling bark Isabella from 1841 to 1845 and then as the first mate aboard the whaling bark Ann Alexander from 1845 to 1849. Between the two voyages he married Henrietta Tew (1808-1883) who was also from Newport. A new bride was not enough to keep Deblois ashore; he departed on a voyage shortly after the wedding, leaving Henrietta to care for her mother and manage her husband’s affairs. The couple’s surviving letters reveal that they were very much in love.He frequently wrote of his longing for his wife and how he wished that she could join him at sea. Henrietta was lonely for her husband as well, writing to him in November of 1846, “I am so glad one year of your voyage has passed and that you are not just going to begin a voyage, do come as soon as you can.” In that same letter she asked that he take her with him on his next voyage as she believed he would soon become a captain.

Henrietta was correct. In 1850 Deblois was promoted to the position of captain aboard Ann Alexander, but Henrietta did not join him on his first voyage as commander. Perhaps it was for the best. That voyage ended in catastrophe yet it made Deblois one of the most famous whaling captains of his era. On June 1, 1850 Captain Deblois and his crew sailed Ann Alexander out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. While it is not known why Henrietta did not join her husband, it is possibly because she was the caretaker for her aging mother, Eliza Grimes Tew (1772-1854).[2] John was clearly sad to leave his wife, writing to her just eight days into the voyage of how much he missed her.

By August 20, 1851, Ann Alexander was in the “Off-Shore” ground of the Pacific Ocean when Deblois spotted a large sperm whale. He ordered the crew to lower two whaleboats to begin the hunt, with Deblois in one boat and the first mate in the other. The whale surfaced near the First Mate’s boat and the crew harpooned it. The whale became enraged, turned, attacked and destroyed the whaleboat. Deblois, in the second whaleboat, successfully rescued all of the distressed men. Not deterred by the attack Deblois ordered a third boat to be lowered from Ann Alexander. The crew was divided between the two small boats and proceeded to give chase. The whale turned and attacked again, destroying one of the boats. Once again Deblois rescued his crew and resolved to continue the pursuit of the wounded whale from the safety of Ann Alexander itself. After several hours of chase, the whale turned toward the vessel and rammed its hull. While water rapidly flooded the cabins of Ann Alexander, Deblois ordered his crew to abandon ship. Split between two boats, they spent a terrifying night at sea. At daybreak they returned to the wreck to salvage what rations they could before setting a course for the north. Two days later, on August 22, they were spotted by the crew of the whaling bark Nantucket. [3]

Newspaper accounts of this incident portrayed Captain Deblois as a hero, and in the fall of 1851 his celebrity grew after the publication of Moby Dick, which tells the story of a whaling vessel that was sunk by an enraged leviathan. The novel was inspired by the true story of the Nantucket whaleship Essex, which was attacked and sunk by a whale in 1820. The American public compared John Deblois to Melville’s fictitious character Captain Ahab. In a letter to a close friend, Melville commented on the coincidence that Moby Dick was published contemporaneously with the destruction of Ann Alexander. “It is really & truly a surprising coincidence-to say the least. I make no doubt it is Moby Dick himself, for there is no account of his capture after the sad fate of the Pequod about fourteen years ago. Ye Gods! What a Commentator is this Ann Alexander whale. What he has to say is short & pithy & very much to the point. I wonder if my evil art has raised this monster.” [4] It is the inspiration behind Melville’s story that is the focus of Nathanial Philbrick’s book In the Heart of the Sea: the Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, published in 2000, and the 2015 Ron Howard film of the same title.

Undaunted by the misfortune of his first voyage as commander, Deblois continued his career as a whaling captain. While at sea, he regularly corresponded with Henrietta, sharing event details, but most often writing of how he missed her. Finally in 1856 he brought her along. From 1856 to 1859, Henrietta joined her husband on a voyage aboard the whaling bark Merlin where she chronicled daily life in a private journal recording personal thoughts about her husband and the crew of the Merlin. [5] Beginning with her first day aboard the Merlin, June 25, 1856, she reveals that while she was happy to be with Deblois she was often scared—but determined to not let it show. “We came on board in a small boat . . . when the boat took in water I looked at the others and seeing them unconcerned I knew there could be no danger so kept my thoughts to myself.” Henrietta describes life at sea, from daily activities on calm waters to cries of “There She Blows!” October 20, 1856: “Monday 20 Directly after breakfast Captain [6] came down to get his instruments to draw a tooth for Kelly while drawing they saw whales. He pulled the tooth dropped instruments and was at the mast head in less than no time.”

Her journal records the latitude and longitude of the ship and describes the processing of the whales. October 21, 1857: “Lat 35.04 S, Long 51.03 W “At work cutting and boiling. It is said to be unusually good weather for these latitudes . . . the outside skin of the whale had left its traces not only on [Deblois’s] shirt and pants but his face and hands are disfigured. Never mind this dirt will bring him clean money I hope and prevent him having to work all his days.” Henrietta also writes of sickness, loss of life and burial at sea. April 17, 1858. “The man covered with the American Flag lay on deck . . . everyone goes softly about as if afraid of disturbing his slumber.”

During the voyage there were visits to exotic ports like Paita, and encounters with other ships where she occasionally met captains’ wives who, like Henrietta, had followed their husbands to sea. July 4, 1858. “Captain and Mrs. Gibbs came on board to dine.

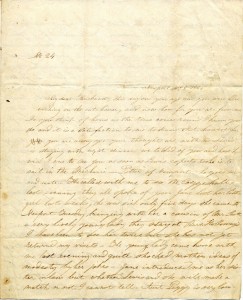

Cover page of letter from Henrietta Tew Deblois to her husband, dated Nov. 5, 1845 (John S. Deblois Papers, Newport Historical Society Collections)

They brought me a beautiful knife. Henrietta often wrote of the love she had for her husband, but also implored God to keep them all safe. Three years at sea must have taken its toll on Henrietta; her journal entries in 1859 increasingly reference home. On January 9, 1859 while in the “Off Shore” grounds of the Pacific Ocean she wrote, “Every whale now appears to bring us nearer to home.” May 26: “It seems like a dream going home so soon, so much sooner than anticipated.” Although she seems to have felt conflicted as the ship drew nearer to New England. June 15: “I hardly can define my feelings I wish to see my friends but dread the change from the quiet life . . . 518 miles from home. June 16: “Oh may we be adjusted to live a Christian life on shore.” June 18, 1859: “Home Sweet Home.”

In 1860 the Merlin left for yet another whaling voyage. This time Henrietta did not go. There is no recorded reason for absence from the voyage. John Deblois wrote to her often, urging her to join him. July 8, 1860 “It is no use my dear Henrietta I can not be happy without you.” June 30, 1861 “ My dear wife you can not think how glad I shall be to see you all I can say is do come to me if it be safe to you to come I don’t mind what it will caust or the experience.” He ended most of his logbook entries with “good night my dear wife.” [7]

Henrietta did not respond to her husband’s pleas to join him aboard the Merlin. Deblois eventually gave up whaling and settled with Henrietta in Newport at 108 Church Street in the location that is now the parking lot for the Viking Hotel. They did not have any children. While little is known about the couple’s life upon retiring from their days at sea, their story represents a remarkable part of 19th century history. The Newport Historical Society holds their papers and other related collections that were donated by their grandniece Lillian Fox. Much more can be learned by studying the Deblois letters and Henrietta’s journal, which are available for researchers and scholars to review by making an appointment at the Society’s Resource Center.

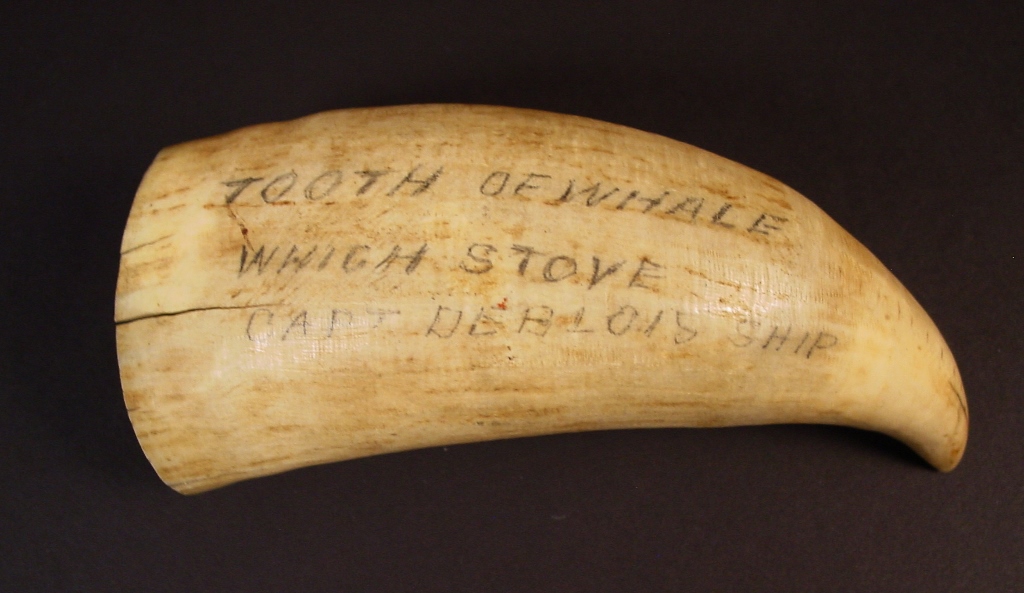

[Banner Image: In early 1852, the crew of the Rebecca Sims killed a whale in the Pacific Ocean that had two harpoons and several pieces of ship’s timber embedded in its skin. After reading the markings of the harpoons, the crew realized that this was the same whale that had sunk Ann Alexander. This tooth was taken from the whale and engraved in memory of the event before being presented to Captain Deblois (Newport Historical Society Collections)]

Co-author Ingrid Peters is Deputy Director and Director of Education, and co-author Elizabeth Sulock is Manager of Public Outreach and Living History, both for the Newport Historical Society. Elizabeth was editor of Newport History Bytes: 50 Fast Facts, which won an award for New England museums in 2015. The book was inspired by History Bytes written by Bert Lippincott and other members of the Newport Historical Society. It is on sale in independent bookstores and gift shops in the Newport area, including the Historical Society’s Gift Shop at Brick Market.

Footnotes

[1] The letters quoted in this article belong to the John S. Deblois letters, 1844 – 1860, Newport Historical Society, Box 113. [2] The majority of Deblois’s letters to Henrietta are addressed to Henrietta and her mother. Henrietta’s mother was Eliza Grimes Tew, 1772 – 1854. Henrietta joined her husband at sea on the voyage following her mother’s death. [3] “Thrilling Account of the Destruction of a Whale Ship by a Sperm Whale – Sinking of the Ship- Loss of the Boats and Miraculous Escape of the Crew,” The New York Times, November 5, 1851. The account of the destruction of Ann Alexander by a whale was recorded in several contemporary newspapers, including the Boston Journal, Boston Semi Weekly Courier, and Daily National Intelligencer. For more information also see Sawtell, C.C. The Ship Ann Alexander of New Bedford, 1805-1851. Mystic: Marine Historical Association, 1962. [4] Parker, Hershel. Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 1, 1819-1851. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, 878. [5] Deblois, Henrietta Tew. Journal of Henrietta Tew Deblois, 25 June, 1856- Jan 2, 1860. Newport Historical Society, Box 113. Documenting her time aboard the whale ship Merlin. [6] Henrietta often referred to her husband as Captain or Blois in her journal. [7] Deblois, John S. “Remarks on Board Bark Merlin of New Bedford, J S Deblois, Master,” Log of the whaling bark Merlin, June 1860 – 19 February 1863. Newport Historical Society, Box 113.