In 1863, Providence photographer Francis Hacker bragged he’d photographed one thousand public buildings and manufactories. In a city with close to fifty-one thousand residents, that’s one picture for every fiftieth person. It was a staggering claim for someone who’d lived in town for approximately a year. If true, then those images would document Providence during a period of great social, economic and architectural change.[1]

Mid-nineteenth century photography took many forms from cased images small enough for a jacket pocket to large format mounted prints. Successful photographers needed talent and expertise to attract clients. Hacker had both.

Francis Hacker was born in Vassalborough, Maine in 1827 to Jeremiah Hacker and Sarah (Reed), both members of the Society of Friends. Francis began his career as an artist in Augusta, Maine, in approximately 1850. He first appeared in the Providence City Directory of 1852 as a daguerreotypist, a maker of shiny reflective images on silver coated copper plates, with a studio at the rear of 24 Angell Street. It was a short-lived stay. He didn’t appear in city directories for Providence again for eleven years.[2]

According to ads in the Vineyard Gazette in 1852, 1853 and 1855, he operated a studio in Martha’s Vineyard over the store of Frederick Baylies, Main Street, Edgartown. He offered hand-colored crayon daguerreotypes, lockets and miniatures. In 1855 his ego is unsurpassed. He refers to himself as an “unrivaled Daguerrean artist,” having been in practice for five to six years in the best studios in New England.[3]

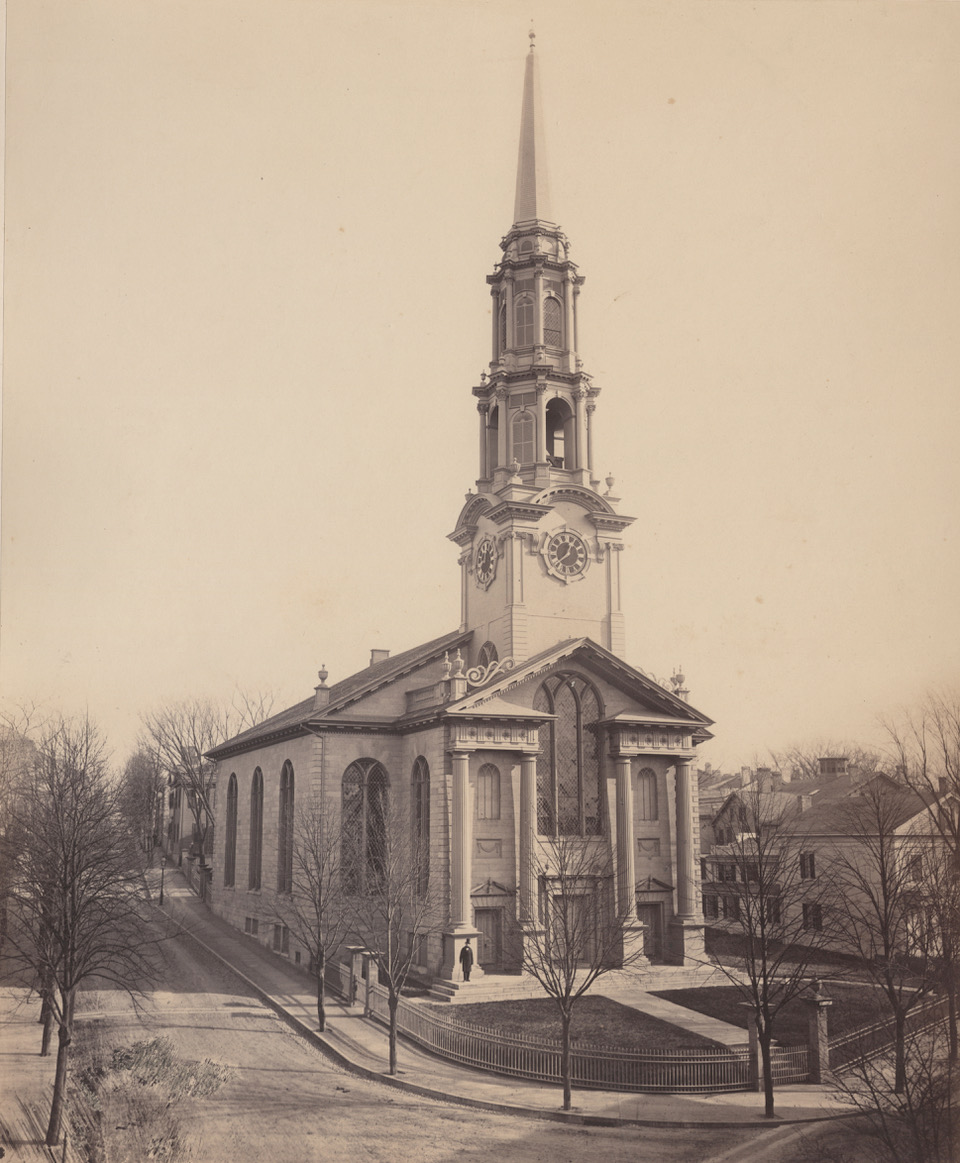

The Unitarian Church at the corner of Benefit and Benevolent Streets, with Pastor Edward B. Hall in a stovepipe hat on the steps at 12:40 pm on a winter afternoon, ca. 1860s (Lee Gallery)

The intervening years (with gaps) saw him marrying Charlotte Mayo Hallett in 1857 in Chatham, Massachusetts. The couple had their first child in Michigan in 1862. The marriage record shows that he’d left the struggling business of making likenesses for employment as a real estate broker in Superior, Wisconsin. An F.W. Hacker operated as an ambrotypist in Houghton, Michigan, in 1859 and 1860 creating images on glass.[4]

Beginning in 1863, the Hackers are in Providence for an extended stay. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen men working in the photography industry in Rhode Island’s capital city.

Like most photographers in the period Hacker opened studios in the business district of Providence concentrating on Westminster Street. He had a studio in two rooms on the third floor of the Arcade in 1863 at 61 and 65. Nearby A.E. Alden’s studio occupied 60 and 62. Both men advertised on the first page of the 1864 city directory containing color advertisements, a placement that called attention to their businesses and their competition.[5]

From advertisements it’s known that Hacker took pictures from small cartes de visite (2 ½ x 4”) to images suitable for framing at 22 x 40 inches. His building views were popular as stereoviews, a card of two nearly identical photographs that look 3-D when gazed at with a special viewer. Like many of his competitors he was in the business of copying earlier photographic formats such as shiny daguerreotypes and glass ambrotypes. Hacker proudly proclaimed that customer satisfaction was foremost. “ We do not ask you to take pictures unless they are perfectly satisfactory.”[6] The slightest movement could blur a portrait.

In views recently made available as a result of a family sale, one can step back into the Providence of the 1860s. It was a time when the downtown was transforming from residential buildings to commercial ones and when wood framed structures were being replaced by stone or brick.

Hacker shot images at street level, like the view of the intersection of Westminster Street and Exchange Street in this article. The view is not recognizable today. Someone took ink and wrote in the margins that the buildings on the right are where the Industrial Trust building now stands. The reference to that building suggests the annotation was done after 1892.[7] In the background are Exchange Street and the Union Passenger Depot (1848-1896). A group of men stand in the doorway of the building housing the New York Life Insurance Company. A ghostly figure stands in the left foreground—he moved before the picture was fully exposed.

The exact location of the photographer in this picture is unknown but it’s likely one of the churches along Westminster Street, possibly Grace Church, built in 1845. Ink annotations identify the Howard building on the left and the Arcade on the right as well as the dome of the Custom House and the spire of the Unitarian Church. Ca. 1860s (Lee Gallery)

Hacker climbed to the highest buildings in the city to capture views in all directions for his stereoviews, selling these photographs as large format prints. E.G. Windsor and Co. offered his photographs for sale.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, a Hacker photograph appeared for sale in regional newspapers an image of an actor in costume and titled, “Vision of Booth, the Assassin.” The photograph of the assassin of President Lincoln had mass-market appeal.[8]

The economic depression that followed the Civil War wasn’t kind to businesses of all types, including photographers. A notice in the Providence Evening Press reported that the Vineyard Gazette claimed that Hacker was preparing two hundred and fifty pages to be bound in Turkish leather and featuring twenty or more images of the Vineyard Camp Ground. Hacker, apparently, was going to charge subscribers fifteen to twenty dollars per copy. The following year Hacker, however, filed for bankruptcy in Providence.[9]

Francis Hacker’s studio in Providence, the Taylor-Grinnell House at 80 Westminster Street, ca. 1860s (Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, RHiX173249)

It wasn’t just the buildings of Providence that captured Hacker’s imagination. In 1879, he took a journey to Washington, D.C. and shot a panoramic series of images of nation’s capital for an accordion folded tourist trinket. In one, the partially constructed Washington Monument is visible. You can view these on the Library of Congress website www.loc.gov (click on Researchers, click on Prints and Photographs, and search for “Francis Hacker”).

In the 1890s, Hacker was still in business in Providence, but he called his company the Hacker Photograph Co., and called himself an agent not a photographer. By 1894 he’s no longer listed in city directories for Providence. He retired to Brant, Ontario, by 1901 and died there in 1904.[10]

Not all of Hacker’s 1863 images are identified. It is possible that many of them are unattributed. Examples of his work are in the collections of the Rhode Island State Archives, The Providence Public Library and the Rhode Island Historical Society. The images in this article are at the Lee Gallery in Winchester, Massachusetts.

[Banner image: Westminster Street, image taken March 11, 1869 and annotated after 1892 (Lee Gallery)]

All images appearing in this article may be viewed in the collection of the Lee Gallery, Winchester, Massachusetts (www.leegallery.com) and are reproduced with its permission.

- Providence City Directory. 1863; Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places, 1860 https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab09.txt

- “Friends’ Records at Vassalborough, ME,” The New England Historical & Genealogical Register, 1847-2011 (available online at ancestry.com), 69:175.

- “Sky-Light Daguerreotypes,” Vineyard Gazette, June 4, 1852; “Improved Daguerres, Edgartown,” Vineyard Gazette, June 10, 1853; “Hacker, The Unrivaled Daguerrean Artist… Edgartown,” Vineyard Gazette, July 20, 1855.

- Massachusetts Vital Records 1841-1910, 108:6; Totten, “John Reynolds,” Thacher-Thatcher Genealogy (New York: New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, 1910), 668; 1870 United States Federal Census, Providence, Rhode Island, Francis Hacker, dwelling 523, family number (available online at ancestry.com); Massachusetts Vital Records 1841-1910, 108:6; “Francis Hacker,” http://craigcamera.com/dag/

- Providence City Directories, 1863-1869.

- Providence City Directory, 1869, 375.

- This refers to the first Industrial Trust building (1892) that stood on the site of the old Hamlin Building visible in this photograph. It’s likely that Hacker annotated this print. He was still in Providence in 1892.

- This card photograph appeared in an exhibit at the Huntington Library called A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War (Oct. 13, 2012–Jan. 14, 2013) at http://huntington.org/civilwar/media/ASFI_CHECKLIST_FINAL.pdf

- “A Unique Book, “ Providence Evening Press, August 26, 1867, 1; “Advertisements New This Day,” Providence Evening Press, March 23, 1868, 3.

- Providence City Directories; 1901 Census of Canada, Brant, Ontario (available online at ancestry.com).