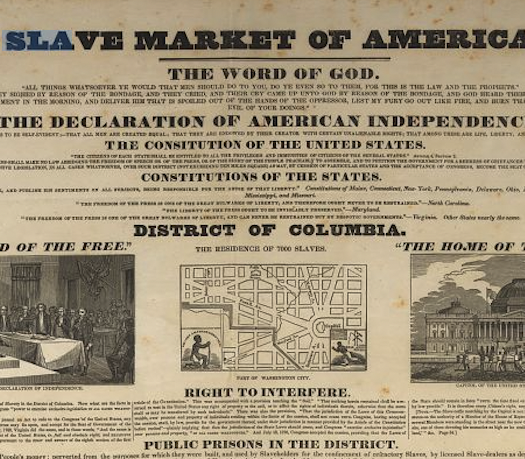

Once upon a time an Italian count fell in love with a daughter of one of Rhode Island’s most elite families. The blissful marriage ended sixteen years later with Caroline Brown Bajnotti’s unexpected death in 1892. In her memory Providence received a grand baroque fountain in Burnside Park near Kennedy Plaza and an imposing clock tower on the Brown University campus—both gifts to the city from her devoted and bereft husband.

The late 1800s was a time when America’s Gilded Age heiresses sometimes married into titled European families, bringing with them infusions of new money. It was an exchange of cash for social status that enabled those titled families to maintain their lifestyles and stately homes. Notwithstanding the fictional Lady Cora and Lord Grantham, late of Downton Abbey, many of such marriages were loveless matches, like that of the unhappy Consuelo Vanderbilt who was forced by her feminist mother Alva to marry the ninth Duke of Marlborough.

Carrie Mathilde Brown’s story is different. She was born in 1841, a daughter of Providence East Side privilege. She and her sister Annmary were the granddaughters of Nicholas Brown, Jr., who gave $5,000 to the former College of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations and won naming rights resulting in the renaming of the school to Brown University. Their father, Nicholas Carter Brown III, was “a gentleman of the old school, an exemplar of democracy who judged people on their acts, not their possessions,” according to Carrie’s future brother-in-law, Colonel Rush Hawkins.

Annmary and Carrie Brown as children, at the Annmary Brown Memorial, Brown University (Brown University Portrait Collection)

Nicholas Carter Brown’s daughters inherited these admirable qualities. Carrie had “a childlike frankness of conduct and unreserved confidence. She was the embodiment of openness and sunshine, with an affectionate nature and a loving heart,” wrote Colonel Hawkins in a tribute to her after her death.

The education of the Brown daughters began in Rome when their father was appointed U.S. Consul to the Vatican by President James Polk. Though Episcopalian, Carrie attended Roman Catholic convent schools in Rome and became especially proficient in music and languages. These talents would become useful in the future.

When Nicholas Brown‘s service in Rome ended in 1854, the Brown family returned to Providence. They summered at Choppequonsett, the family home on the Warwick waterfront, an area now known as Salter’s Grove.

Despite their fortunate birth and successful marriages to men who obviously adored them, there were 19th century echoes of La Traviata in the lives of the Brown sisters. Annmary was a semi-invalid who suffered from respiratory ailments her whole life. Her portrait depicts a beautiful woman with unnaturally white skin and dark circles under her eyes. Her younger sister devoted herself to Annmary’s care during her frequent illnesses and willingly “gave up the allurements of society” according to Colonel Hawkins.

Despite her illness, in 1860 Annmary married Rush Hawkins, a New York attorney who was devoted to her. Hawkins established the first regiment formed in New York City when the Civil War broke out the next year, and he commanded the colorfully attired “Hawkins’s Zoauves” in the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia.

While her husband was away at war, Annmary was frequently ill. Carrie was her caregiver and companion, reinforcing the uncommonly close bond between the sisters.

In his tribute Hawkins recalls that in Paris in April 1873, when he was blinded by an eye inflammation for five months and Annmary was also ill, Carrie was always with them. The younger woman “was her sister’s constant companion, to comfort, encourage and cheer her during this time.”

After the war, Annmary and Rush Hawkins traveled through Europe, the South, and California, always searching for a climate that would improve Annmary’s health. Meanwhile, back in Providence, Carrie enjoyed a wide circle of friends and the life of a young woman about town. The capital city was entering its glory years—a booming city on two hills that was growing wealthy from trade and manufacturing. Gorham Silverware, Brown and Sharpe, Corliss Steam Engine Company, Nicholson File and other industrial giants built giant factories in this “beehive of industry.”

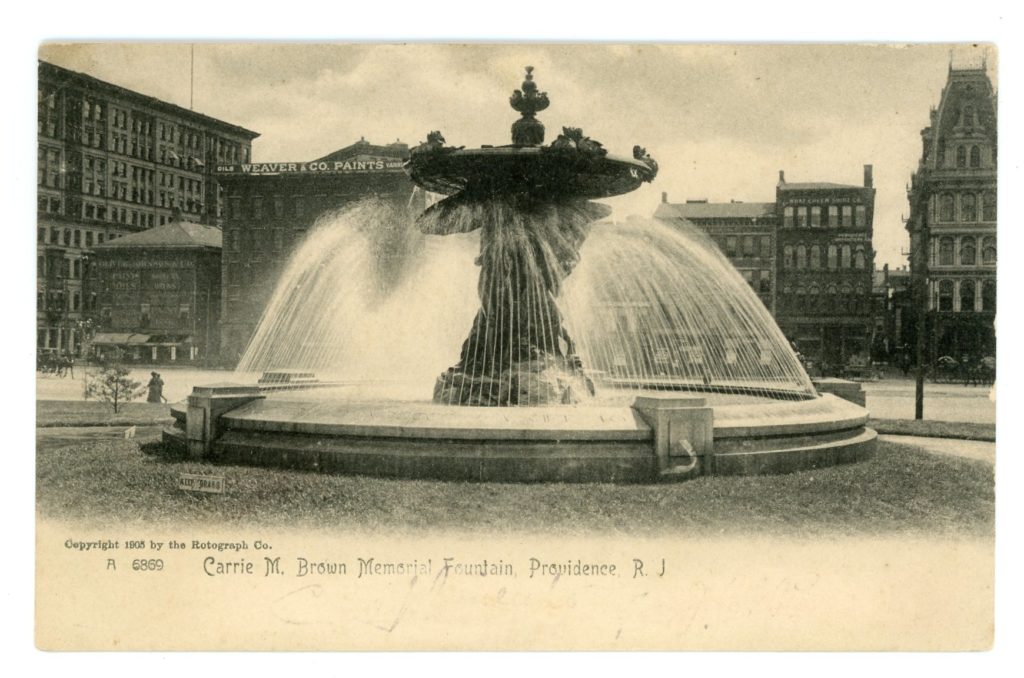

Here it is called the Carrie M. Brown Memorial Fountain. It was commissioned in 1898 and completed in 1902. Note the keep off the grass sign in this 1905 postcard (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

By the time Carrie was in her thirties, with the dreaded status of spinster, she probably never expected to marry. But in the summer of 1875 she met Count Paul Bajnotti of Turin, Italy’s major industrial city. (The Bajnotti name is pronounced bye-knottee). He was in the diplomatic service for the newly unified Italy and served as vice consul of New York City. Like Carrie he was also accomplished in music and languages. The two apparently met each other at a party in Providence and fell in love. They married on June 17, 1876, at the Brown summer home on Choppequonsett.

The newlyweds honeymooned in Italy and returned to New York City. After his posting in the United States ended, Paul was sent to Paris as vice consul, then to St. Petersburg, and next Chicago. Those years must have been glamorous and exciting for the happy couple. During his diplomatic assignments the Count and Countess Bajnotti mingled at the highest circles of cultivated and sophisticated elites. It was said that their marriage was one of the happiest ever by members of different nationalities.

Through their travels in Europe and trips back to the United States, the Bajnottis had the happy coincidence of frequent visits with Annmary and her husband, Colonel Hawkins, who led a peripatetic lifestyle, always searching for a climate that would improve Annmary’s health. Neither couple had children, and the brothers-in-law enjoyed each other’s company, so the foursome spent pleasant times together. In October 1891, Paul and Carrie left for Europe and the parting was particularly poignant, according to the Hawkins memoir. Annmary was recovering from a bout of pneumonia and the sisters realized that it might be the last time they would see each other.

It was, but not because of Annmary’s illness. In fact it was Carrie, always the healthy one, who succumbed to the 19th century scourge of respiratory disease. In the spring of 1892 Carrie and Paul went to Sicily to view an exposition in Palermo. Though still weakened by an earlier bout of influenza, Carrie wrote to her brother-in-law on March 27th that she was enjoying drives around the city. But shortly after that letter was sent she developed pneumonia and a high fever. After eight days of great suffering during which Paul never left her side, Carrie died in his arms on April 6th. Her last letter to Colonel Hawkins arrived on the same day, only a few hours before the official cable announcing her death. She was only fifty-one years old.

Following her wish Carrie was buried in the English Cemetery in Rome because “birds came so early in the spring and the feathered friends she loved might sing their joyous songs above her grave.”

In his memorial to his sister-in-law, Hawkins wrote that “her death wreaked the life of the one who survives with an everlasting sorrow.” To us that sentimental prose may sound like Victorian hyperbole, but five years after she died Paul commissioned the Carrie Brown Memorial Fountain for downtown Providence (known as the Bajnotti Fountain) and later the Carrie Clock Tower on the Brown University campus.

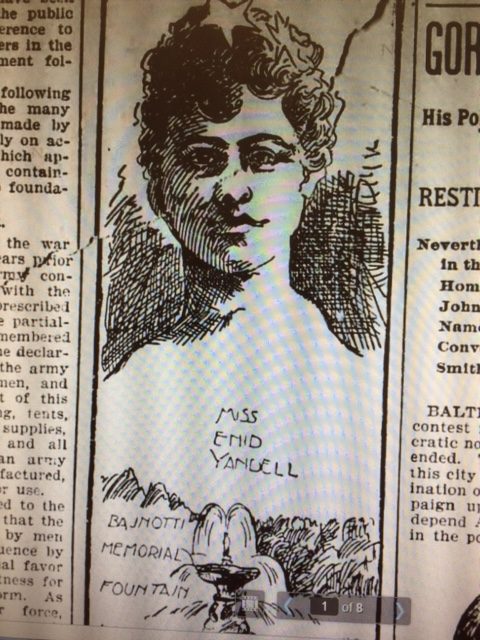

Eighteen sculptors entered a competition to design the memorial fountain. The winning entry was a twenty-foot-high baroque fountain with the central figure of an angel straining to break free from the earthly restraints of duty, passion, and greed, represented by three male figures. Titled “The Struggle of Life,” it was an allegorical representation in the 19th century style of a spiritual ideal. It was designed by Enid Yandell, a young woman who had studied in Paris under Auguste Rodin and who entered the competition uninvited.

Drawing of Enid Yandell in an article about her being the designer of the Carrie Banjotti Memorial Fountain

Though Miss Yandell had not been asked to submit a design (because a woman was not expected to be able to design a monumental sculpture), it was agreed that hers was the equal of any of the men who entered the competition. The figures exude energy and strength and reflect the influence of her great teacher. The composition is crowned with a basin from which water flows out of spigots in the shape of fish. The inscription on its base reads, ERECTED ADMDCCCC A GIFT TO HONOR THE MEMORY OF CARRIE MATHILIDE DAUGHTER OF THE LATE NICHOLAS BROWN FROM HER HUSBAND PAUL BAJNOTTI OF TURIN, ITALY.

Paul Bajnotti was an art collector who weighed in with his own ideas. The piece had to be bronze (cast by Gorham Manufacturing Company) rather than marble because the metal would better withstand the city’s industrial pollution. The heartsick widower gave the city $10,000 for the memorial to be placed in Burnside Park. It was unveiled in 1901.

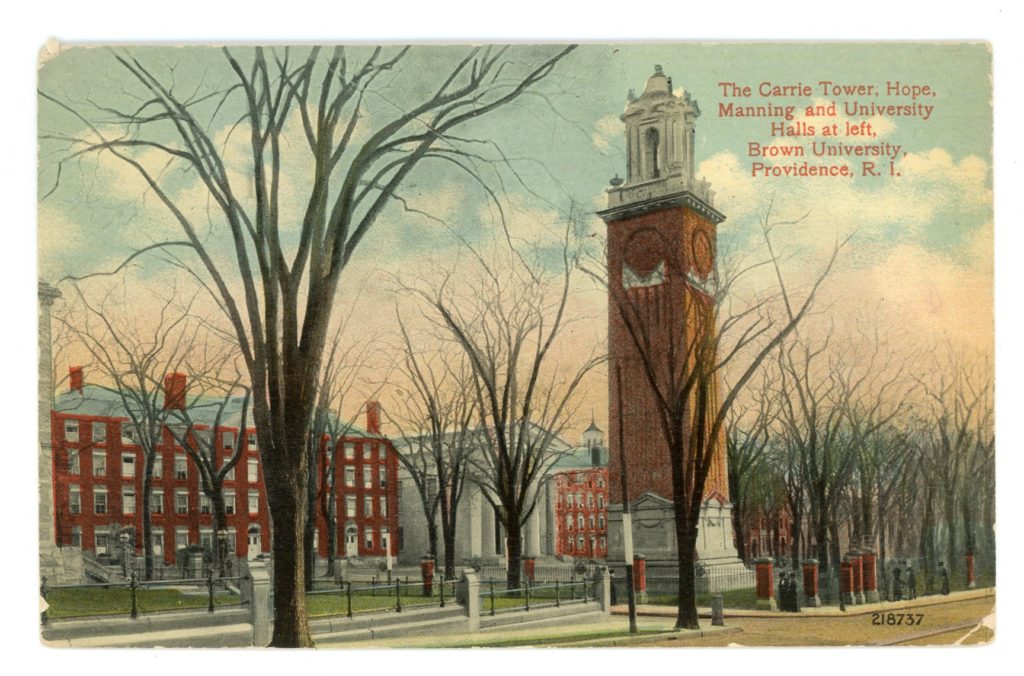

The Carrie Tower, in front of University Hall and Manning Chapel on the Brown University Campus (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

But Paul did not stop with this grand tribute to his wife. In 1904 he gave Brown University the Carrie Tower at the corner of Prospect and Waterman Streets, behind the Manning Chapel and facing the hill overlooking downtown Providence. After a long competition to design the clock tower, Paul chose architect Guy Lowell, who went on to build the Museum of Fine Arts. On the foundation of the 95-foot tower is inscribed “Love is Strong as Death.”

Hawkins wrote, “to her sorrowing and heartbroken husband she carried the full bloom of their maturity, all the fine qualities of her nature; and to the end she was the most affectionate and loyal companion and loving wife.”

What a remarkable woman, and what an extraordinary couple.

Colonel Rush Hawkins built his own memorial for his wife on the grounds of Brown University, completed in 1907, called the Annmary Brown Memorial. It was mostly for his art collection. Both are entombed in a crypt in the rear of the building. (Brown University)

Sources:

Most of the information about Paul and Carrie’s lives is from Rush Hawkins, Tribute to the Memory of Carrie Mathilda Brown (Privately Printed, 1893). A copy is in the collection of the Rhode Island Historical Society.

Paul F. Caranci and Heather A. Caranci, Monumental Providence Legends of History in Sculpture, Statuary, Monuments and Memorials (Stillwater River Publications, 2015).

Robert Freeman and Vivienne Lasky, Hidden Treasure: Public Sculpture in Providence (The Rhode Island Bicentennial Foundation, 1980)

Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, Outdoor Sculpture in Providence (1999).