My last article was on the story behind the recent identification of the remains of the wreck of a vessel off the coast of the Patagonia region in Argentina, which is believed to be the whaling ship Dolphin from Warren. This story has helped to remind us that once whaling was a fairly important business in Rhode Island and that Warren was the leading whaling port in the state.

Of course, the first people in southeastern New England to use whales for food and tools were Indians. As Eric Jay Dolin as written, in his superb history of whaling in America, “The Indians had for many years, and undoubtedly many centuries before that, viewed stranded whales as a commodity, cutting them up and putting parts of the animal to good use, including the meat, blubber, bones, tendons, teeth, flukes, and skin.”[1]

Beached whale being carved up by colonists (Jon Hohn Collection, Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Roger Williams, in his book on the language of the Narragansett that was first published in 1643, writes that the word for “whale” was “pótop” and that the word for “whales” was “pótopaũg.” Williams further writes:

“Pótopaũog in some places are often cast upon shore. I have seen some of them, but none more than sixty feet long. The Natives cut them up in several parcels, and give and send them near and far as an acceptable present or dish.”[2]

The fact that the longest whale viewed by Williams on Rhode Island’s shorelines was no more than sixty feet indicates that many of the whales that washed ashore were likely pilot whales. Interestingly, in the first days of their settlement at Plymouth, Massachusetts, white Pilgrims spotted Wampanoag Indians using tools to work on stranded pilot whales.[3]

Dolin concludes that there is no firm evidence that the Narragansetts or other nearby coastal New England Indians ever hunted for whales at sea, but that that does not mean it did not happen.[4] Roger Williams did not mention it.

The first whaling ship from Rhode Island mentioned in known existing records dates from 1723. The port where it departed, however, is not known. Newport, the dominant port in Rhode Island during colonial times, sent out its first whaler in 1731, followed by Warren in 1766 and Providence in 1768.[5] The Newport whaler may have been influenced by the Rhode Island General Assembly, which in 1731 tried to encourage the whaling business by offering a bounty of five shillings for a barrel of whale oil and one penny a pound for whale bone.[6]

A Newporter apparently won the first bounty in 1733. The General Assembly voted at its June 1733 session:

Whereas it appears to this Assembly, by the certificates of Jonathan Chase and Jacob Barney, viewers of fish, oil and whalebone, for the town of Newport, that Benjamin Thurston, owner of the sloop Pelican, of said Newport, had brought in said sloop, to Newport, one hundred and fourteen barrels of oil, and two hundred weight of whalebone . . . Therefore it is voted and ordered by this Assembly that the said Benjamin Thurston is entitled to and do receive the bounty on the proportionable part of the oil and whalebone belonging to said sloop; she being owned in this colony and sailing out of Newport.[6.2]

Perhaps because encouraging whaling was no longer necessary, the bounty for whale oil and whale bone ended in 1744.[6.5]

Unfortunately, whalers from Rhode Island could not always avoid foreign interference. In the fall of 1773, Gideon Almy of Tiverton paid for fitting out two-thirds of the sloop Sally for a whaling voyage, and Nathaniel Stoddard paid for the remaining one-third of the costs. The sloop met “with success” in whaling, having got on board “one hundred twenty barrels of oil by the later end of January following.” However, the sloop was forced into seeking cover in a bay in the Caribbean island of Hispaniola during a fierce storm and was then seized by a French warship and carried into the French-controlled port of Port-au-Prince (in what is now Haiti). The whaling ship and its valuable cargo were condemned as a prize in judicial proceedings at Port-au-Prince and sold, presumably with the sales proceeds to be shared in by the French warship’s officers and crew—and the island’s governor. This occurred even though Britain and France were not then at war. Almy and Stoddard submitted a petition to the General Assembly, claiming that the loss (apparently $3,000) rendered them unable to care for their large families and asking for authorization to operate a lottery to raise money for them. The General Assembly approved the request at its June 1774 session.[6.8]

The October 23, 1766 edition of the Boston News-Letter stated, “Several vessels employed in the whale fishery, from the industrious town of Warren in Rhode Island colony, have lately returned having met with considerable success. One vessel, which went as far as the Western Island, brought home 300 barrels of oil. Some vessels from Newport have also been tolerably successful.”[7] A total of 300 barrels was a small amount compared to later years, but it was a start.

In colonial times, Rhode Island was better known as a manufacturer and seller of spermaceti candles than sending out whaling ships to take sperm and other whales. Jacob Rodriques Rivera, a Jewish merchant who emigrated from Portugal to Newport, began manufacturing the candles in 1748. John, Nicholas, Joseph and Moses Brown had developed one of the largest spermaceti candle business in all of the colonies. Rhode Island merchants purchased most of the product to make the candles from Nantucket whalers. From 1768 to 1772, Rhode Island merchants shipped to foreign destinations £66,327 worth of spermaceti candles, more than the value of each of rum, fish, livestock and lumber shipped by Rhode Island merchants to foreign destinations during the same period. Rhode Island merchants also shipped in the same period £32,875 worth of whale oil.[8]

The spermaceti candle and whale oil businesses collapsed during the American Revolutionary War. During the war, Warren lost fourteen whaling vessels, mostly to British warships.[9]

Newport lost whaling ships during the war too. For example, on June 21, 1776, the whaling ship Cleopatra, James Fitch commander, sailing out of Newport, was captured by a British warship off Barbados. The Cleopatra, a 110 ton whaler carrying four cannon and manned by a crew of thirteen, was returning from whaling off the coast of Brazil and had on board 340 barrels of whale oil.[9.5] Now the vessel and its cargo were the property of the Royal Navy and were sold at the British island of Antigua. Its crew were British prisoners too. With the risk of these types of losses, during the war Rhode Island merchants ceased investing in whaling voyages.

It is not known if the buildings British soldiers burned during the raid of Warren on May 25, 1778 included any of the waterfront whaling and spermaceti oil works. They likely did even if inadvertently. Prior to the raid in 1778, Rhode Island authorities sold at public auction for 490 pounds spermaceti oil stored at Warren that was the property of Newport merchants Moses Levy and Jacob Isaacks. It is not known if Patriot authorities believed Levy and Isaacks were Tories and should have the property confiscated or that the oil sitting in a warehouse was at risk of being seized by the British who occupied Newport and needed to be moved. In any event, the Newport merchants were reimbursed by the General Assembly after the war.[9.7]

Whaling did not start up again in Rhode Island in a serious way until the 1820s. Then it became a much bigger business. Whales were an important commercial product in the 18th and 19th centuries. The main product was oil used to light lamps and as an industrial lubricant. Other products included wax for candles and soap, and whale baleen used for small household items.

The whaling bark Canton from New Bedford in the early twentieth century (Nicholson Whaling Collection, Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

From 1821 to 1861, an average of 16 whalers per year sailed out of Warren, each with a crew averaging about 25 officers and sailors. The average annual total of the products brought back, according to local Warren historian Walter Nebiker, from sperm oil, whale oil and whale baleen, would have been worth about $8.5 million today.[10]

Shipbuilding for the whaling industry was also a big part of the local economy. Whaling ships were built in Warren that sailed out of other, more prominent whaling ports, such as Nantucket and New Bedford. The Dolphin, which wrecked off the coast of Argentina, was built in Warren at the Chace and Davis yard. Other shipyards included Sylvester Child’s yard at the foot of Baker Street, Captain Rufus Trink’s yard at Company Street, and James J. Cady’s shop at the bottom of Washington Street. According to Nebiker, “Jon Throop was a noted shipmaster and builder, and others included Caleb Carr, Caleb Eddy, Samuel Miller, James Easterbrooks Bowen, Daniel and John Luther, and a man called Daddy Lee.”[11]

Whaling ships had to be both fast (to get to the far away sailing grounds) and sturdy (to survive storms and rough seas). Whaling ships had killed so many whales off the coast of North America and in the Atlantic Ocean that the whale populations there plummeted. This forced whalers in the 19th century had to sail around Cape Horn to reach the rich whale hunting grounds in the vast Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean. Some of the whalers did not make it.

A history of Warren by Elizabeth S. Warren for the Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission includes the following about the port’s whaling past:

“Whaling, begun in Warren before the Revolution, was revived in 1821. Joseph Smith, a prominent shipowner, fitted out the Rosalie for a trip to the Pacific. Although her first voyage of three years duration was judged a failure, on her second cruise 101 whales were taken by Captain Joseph Gardner and Charles F. Brown, first mate. This venture began a whaling boom which lasted for nearly forty years with many merchantmen converting to the whaling trade. By 1845, twenty-two whalers, the last of their class in Rhode Island, were sailing from Warren. Warren was the leading Narragansett Bay whaling center with over 7,000 tons of shipping employed in the trade. The 806 ton Sea-Shell of Warren was the largest whale ship in the world and the Dolphin, Capt. Charles R. Cutler, the fastest of the Warren ‘Clipper’ whalers.”[12]

The same history states that from a list of Warren whalers built between 1824 and 1842, eight were built at nearby Barneyville and seven at Warren. In Warren Chace & Davis constructed Hector (1842), the ill-fated Dolphin (1850), and Belle (1852), while Daniel Foster built the massive Sea Shell (1852) and Xantho (1856). From other ports in Rhode Island, one was constructed at Providence (the Smithfield in 1838) and one from Westerly (the Galen in 1820). Thirteen of the whalers were built in Massachusetts. It is likely all of these ships would have been outfitted in Warren.[13]

The whaling bark Josephine from New Bedford in the early twentieth century. The last whaler departed Warren in 1861, but whaling continued for decades more in New Bedford (Nicholson Whaling Collection, Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Warren must have had a bustling waterfront from 1830 to 1850, with whaling ships being outfitted with provisions and whaling gear, ready to depart for far away oceans, and with whalers returning from years’ long voyages, filled with hundreds of barrels of oil and sailors anxious to get ashore. Whaling made some fortunes for ship owners in the first part of the 19th century. Other businesses and workers would have thrived as well, such as shops that employed shipwrights for building whalers, rope winders for rigging, coopers for making barrels, blacksmiths, anchor makers, and sail makers.

Some of the Greek Revival and early Victorian houses still existing today in Warren were built in part with money from whaling, as are some commercial buildings. For example, the original “J. J. Smith’s Oil Works” and “F. Marble’s Blacksmith Shop,” both built around 1840, still stand on Water Street. The “Capt. J. C. Joyce House,” circa 1850, a 2 and ½ story gable roof Greek Revival house on Water Street at the corner with Main Street, was built by a Warren whaling captain. The Eddy-Cutler house at 30 State Street, noteworthy for its Palladian window, was constructed by Warren slave trader Benjamin Eddy, and later was purchased by Captain Charles R. Cutler, the noted whaling captain who once commanded the Dolphin.[14]

Going on a whaling voyage was not for the fainthearted. A number of Warren whaling ships were lost during their voyages from various causes. We know about the Dolphin becoming stranded and abandoned in New Bay in the remote Patagonia region of Argentina in 1859. Here are some more losses and their causes, from Elizabeth Warren’s history of Warren:

“The November 6, 1852 Warren Gazette reported that whale ship Warren, commanded by Capt. Nathan Heath, was totally destroyed by fire in July in the Anadyr Sea [in the northwestern corner of the Bering Sea, along the Russian mainland], with all hands saved. Two weeks later, the newspaper printed part of a letter from Capt. Almy of the Harvest of New Bedford, in which he says “I saw the Warren, of Warren, burn up on the 6th of the month.

Although the misfortune of the Warren may or may not have been accidental, it is known that five whaleships were lost through the forces of nature, all blown ashore. Two were destroyed in the South Atlantic, the Galen in a snow storm at the Falkland Islands, and the Dolphin, reportedly going on a rock on the Coast of Patagonia. North America went ashore in Australia, in a storm at Swan River, New South Wales.

Interestingly, two Warren ships went ashore only a day apart on the same coast along the east side of the North Island of New Zealand in 1839. On June 12, Atlantic was blown ashore at the Bay of Islands; the next day Brilliant met its fate down the coast, at Poverty Bay.

Two of the ships ended their days in unusual ways. The only ship that disappeared was Jane, the first Mason Barney whaler to sail out Warren, which left Oahu on October 16, 1845 and was never heard from again. Covington, along with a number of other whaling ships, was operating in the Sea of Okhotsk, when it and nine others were captured and burned by the Confederate cruiser Shenandoah. The date was June 25, 1865, several months after the Civil War ended! The destruction of this ship dramatically ended Warren’s whaling days.”[15]

The development of coal gas in the 1840s, and the discovery of petroleum oil deposits underground in Pennsylvania in 1859, triggered the demise of the American whaling industry. The New York Journal of Commerce, in its July 2, 1861 edition, had the following squib that foretold the end of the whaling business: “Discovery and extensive manufacture of coal oil had a most ruinous effect on whaling interests. At New Bedford, there was about a one third decline in the last three years, and it will decline one third more within the present.”[16] According to Walter Nebiker, the last whaler to leave Warren was the Dromo in 1861.[17]

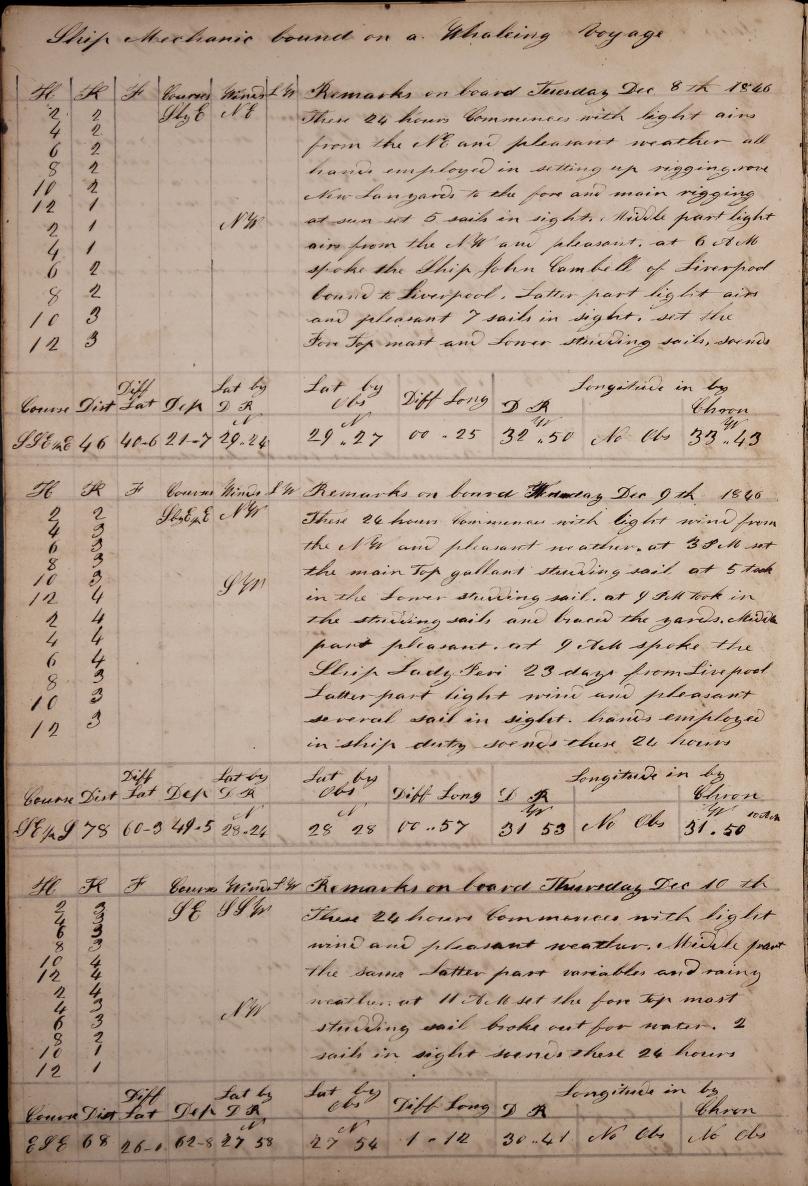

A page from a logbook of the Newport whaler Mechanic, which was commanded by Oliver Potter on a voyage from 1846 to 1851 (Providence Public Library Collections)

The list set forth below indicates that Warren sent out its last whaler in 1865, and that the last whaling ship departed Bristol in 1858, Newport in 1860, and Providence in 1902.

While whaling was important to Warren in the mid-19th century, Warren was not among the great whaling ports in the United States. The number of its voyages pales next to those of the top two whaling ports, New Bedford and Nantucket. Still, on the following list, Warren is in twelfth place for the number of all-time U.S. whaling voyages.

U.S. Whaling Ports, Number of Whaling Voyages, and Years of First and Last Voyages[18]

- New Bedford, Massachusetts, 5,146 voyages, from 1754-1937

- Nantucket, Massachusetts, 2,233 voyages from 1698-1887

- San Francisco, California, 1,171 voyages, from 1849-1930

- Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1,156 voyages from 1789-1915

- New London, Connecticut, 1,116 voyages, from 1718-1908

- Sag Harbor [Long Island], New York, 894 voyages, from 1667-1874

- Fairhaven, Massachusetts, 619 voyages, from 1743-1848

- Boston, Massachusetts, 350 voyages, from 1733-1903

- Westport, Massachusetts, 326 voyages, from 1775-1881

- Stonington, Connecticut, 264 voyages, from 1818-1892

- Edgartown (Martha’s Vineyard), Massachusetts, 237 voyages, from 1738-1894

- Warren, Rhode Island, 199 voyages, from 1766-1865

Warren was the dominant whaling port within Rhode Island, with more than three times as many voyages as Providence, two times as many voyages as Bristol, and almost twice as many voyages as Newport. The full list follows:

Rhode Island Whaling Ports, Number of Whaling Voyages, and Year of First and Last Voyages[19]

- Warren, 199 voyages, from 1766-1865

- Newport, 111 voyages, from 1731-1860

- Bristol, 94 voyages, from 1786-1858

- Providence, 66 voyages, from 1768-1902

- East Greenwich, 6 voyages, from 1807-1811

- Rhode Island (port unknown), 6 voyages, from 1723-1821

- Tiverton, 2 voyages, from 1821-1823

Total Whaling Voyages from Rhode Island: 484 from 1723-1902

Once whaling revived in Rhode Island in the early 1820s, it took a while for it to ramp up. From 1825 to 1839, on the average, Warren sent out about 5 whalers per year, Bristol 4, Newport 2 and Providence 1. But the industry really began to flourish in the 1840s, when on the average, Warren had each year 21 registered whalers, Newport 9, Bristol 6, and Providence 6.

The whaling industry began its decline in the 1850s. From 1850 to 1859, Warren averaged 16 registered whalers per year, Newport 5, Providence 2 and Bristol 0.[20] Bristol abandoned whaling after 1846 and Providence after 1854.[21]

The dominance of whaling within Warren was remarkable. In 1845, whaling ships represented 7,000 tons of the port’s total of 9,000 tons of shipping. By comparison, less than a third of Newport’s fleet (totaling about 3,700 tons) and less than a fifth of Providence’s fleet (totaling about 3,000 tons) was engaged in whaling.[22]

The small port of East Greenwich had six whaling voyages from 1807 to 1811. The main owners of those whalers also likely invested in the whale oil works that stood at the foot of Division Street on Greenwich Cove from 1809 to 1812.[23] It appears the War of 1812 with Great Britain put an end to the business.

Tiverton’s two voyages were made by the brig Amstel. Benjamin Seabury commanded the voyage from 1821 to 1822, while Captain Almy commanded on the voyage from 1822 to 1823. Even though Tiverton claims only two voyages, the Tiverton Historical Society writes, “Like many seaside communities in the area, the people of Tiverton participated in the whaling industry that was centered in New Bedford . . . . Using records kept by the chaplains of the New Bedford Port Society and the New Bedford Free Public Library, it can be seen that at least 324 sailors from Tiverton participated in some 474 whaling voyages from 1812 to 1911.”[24]

Andrews & Eddy Oil Manufactory building, built in 1837, at 337 Water Street, in Warren. Warren’s whaling ships would sell their oil products to this outfit. Other buildings from Warren’s age of whaling still stand on Water Street (Author)

The whaling business and the slave trading business shared some similarities. Newport in colonial times dominated the African slave trade in North America, while Newport and Bristol shared the “honors” from 1784 to 1807 (after which federal law outlawed such voyages). Both whaling and slave trading required crews that were larger than the normal commercial voyage. Both types of voyages also lasted much longer than the usual commercial voyage. An African slave trading voyage could last more than a year, while a whaling voyage to the Pacific Ocean or Indian Ocean could last more than three years. Because the voyages were longer, they required substantial investments. Thus, in both cases, the risk of the voyage was typically spread among a number of investors.

In addition, the captains of both types of vessels were better compensated than on regular commercial voyages. A whaling captain might be entitled to a one-eighth share of the profits. A slave ship captain was often entitled to retain for himself three or four of the surviving captives.

Interestingly, the profitability of the two trading ventures apparently differed. According to Rhode Island economic historian Peter Coleman, “On the average, sperm whalers earned about one and a half per cent annually, right whalers about six and a half per cent.” These were small margins, especially considering that “A whaling syndicate stood to lose $30,000 to $50,000 on an unlucky cruise.”[25] While the profitability of Newport slavers has not been closely studied, extensive studies of British and French slavers showed that they earned on the average a profit margin of about ten percent, which for the times was considered good but not excessive. Newport and other Rhode Island slavers likely earned similar profit margins.[26]

The impressive Eddy-Cutler house at 30 State Street, noteworthy for its Palladian window, was constructed by Warren merchant and slave trader Benjamin Eddy, and later was purchased by Captain Charles R. Cutler, the noted whaling captain who commanded the ill-fated Dolphin (Author)

From 1789 to 1807, Warren sent out thirty ships to Africa to engage in the African slave trade, leading the death or enslavement of more than 2,800 Africans.[27] All of the voyages were illegal under Rhode Island law. By comparison, Warren sent out 199 whaling ships and whaling was then legal.

Robert Cembrola, when he was with the Naval War College Museum in Newport, was quoted as saying about Warren’s whaling past, “The next time you drive or walk along Water Street try to imagine what the bustling wharves and shipyards must have looked like and take pride in our maritime heritage.”[28] There is also a slave marker at the Eddy-Cutler house on State Street.

The Providence Public Library blog has an excellent article on Warren whaling: “Whaling in Warren, Rhode Island: 1821-1860,” at https://pplspcoll.wordpress.com/2010/03/21/whaling-in-warren-rhode-island-1821-1860/. This excellent article was likely done by Walter Nebiker or by someone using his manuscript. The Providence Public Library also has about 65 whaling logs in its Nicholson Whaling Collection, many from Rhode Island. They can be viewed online here: https://archive.org/details/providencepublicnicholson

For those who want to know more about the New England whaling business, one of New England’s finest museums tells the story, the nearby New Bedford Whaling Museum. One can also take a day trip to Nantucket and spend time in its fine Whaling Museum. To the east, and even closer for many Rhode Islanders, is Mystic Seaport Museum, which includes one the last wooden whaleship in the world, the Charles W. Morgan. It was launched from New Bedford in 1841.

For readers, there are two outstanding books. The first is by Nathaniel Philbrick, In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2000), the story of a whaling ship that was the basis of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick novel, and includes an amazing and harrowing survival story of the crew. The second book is Eric Jay Dolin’s Leviathan, The History of Whaling in America (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007). His narrative of the long and colorful history of Nantucket whalers is particularly notable.

There are a number of whaling movies. Of course, there are several versions of Moby Dick, including one from 1930 starring John Barrymore and one (in color) from 1956 starring Gregory Peck, both of whom play Captain Ahab. A more modern movie that has good production values is the underrated In the Heart of the Sea (2015), a retelling of Nathaniel Philbrick’s book, which is good at showing how whaling was done. There is also a history documentary that I have not seen, Into the Deep: America, Whaling and The World (2010).

The majestic First Methodist Church on Church Street in Warren, completed in 1845 and since then a landmark for Narragansett Bay, is a testament to the wealth brought into Warren by the whaling industry in the 1840s (Author)

While it is understandable to romanticize and appreciate New England’s whaling past, it is a good thing that Americans no longer engage in whaling. U.S. whalers killed hundreds of thousands of magnificent whales, leading to their populations to plummet dramatically. For example, there are only an estimated 340 remaining North Atlantic right whales.[29] But we can’t just blame the old-time whalers. A display in the Nantucket Whaling Museum says: “Nantucketer whalers killed approximately 50,000 whales. To put this slaughter in context, more whales were killed in one season in the 1960s, one hundred years after Nantucket was out of the bloody business.” Japan continues to harvest whales using modern ships, a practice that this author hopes ends as soon as possible.

Footnotes:

[1] Eric Jay Dolin, Leviathan, The History of Whaling in America (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007). 36. [2] Roger Williams, A Key Into the Language of America, the Tomaquag Museum Edition, edited by Dawn Dove, Sandra Robinson, Lorén Spears, Dorothy Herman Papp, and Kathleen J. Bragdon (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2019), 100. [3] Dolin, Leviathan, 34. [4] Ibid., 36-37. [5] See chart below in main text, “Rhode Island Whaling Ports, Number of Whaling Voyages, and Year of First and Last Voyages.” [6] C.E. Pesch, E.J. Schumchenia, M.A. Charpentier, and M.C. Pelletier, Imprint of the Past: Ecological History of Greenwich Bay, Rhode Island (EPA/600/R-12/050) (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Atlantic Ecology Division, Narragansett, RI, 2012), 9.[6.2] General Assembly Resolutions, June 1733 Sessions, in John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation in New England, vol. 4 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1859), 483-84.

[6.5] General Assembly Resolutions, June 1744 Session, in ibid., 100. For the bounty in the 1731 resolution being five shillings per barrel on whale oil and one penny per pound on whale bone, see also Report of Governor Ward to the Board of Trade, Jan. 9, 1740, in ibid., vol. 5, 10.

[6.8] General Assembly Resolutions, June 1774 Session, in ibid., vol. 7, 250 and 263-64.

[7] Quoted in Ted Hayes, “Warren Whaling Ship Wreck found in Argentina? Archeologists aren’t sure but suspect wreck could be Dolphin, built here in 1850,” May 29, 2012, The Ocean Update, at https://whalesandmarinefauna.wordpress.com/2012/05/30/warren-whaling-ship-wreck-found-in-argentina/. Hayes apparently relied on to a great extent on an unpublished manuscript of Warren’s whaling history by local Warren historian Walter Nebiker that Hayes indicated was in the possession of the Providence Public Library. Nebiker was unable to finish the manuscript before he died in 2013. [8] See Lynne Withey, Urban Growth in Colonial Rhode Island, Newport and Providence in the Eighteenth Century (Albany, NY: State University Press of New York, 1984), Table B-4, 122 (from British Customs Office records). [9] See “Whaling in Warren, Rhode Island: 1821-1860,” at the website for the Providence Public Library at https://pplspcoll.wordpress.com/2010/03/21/whaling-in-warren-rhode-island-1821-1860/. This excellent article was likely done by Walter Nebiker or by someone using his manuscript. [9.5] See An Account of American Ships and Vessels Taken as Prize of War, by His Majesty’s Vessels, Between 1st and 27th July, 1776, in William James Morgan, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1970), vol. 5, 1254. [9.7] See Bartlett, ed., Records of R.I., vol. 10, 52. [10] Hayes, “Warren Whaling Ship Wreck found in Argentina?” [11] Ibid. [12] Elizabeth S. Warren, Warren, Rhode Island (Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, April 1975), 15. [13] Ibid., 57. [14] Ibid., 13, 18 and 58. [15] Ibid., 58-59. [16] Ibid., 59. [17] See Hayes, “Warren Whaling Ship Wreck found in Argentina?” [18] Derived from information in Judith Navas Lund, Whaling Masters and Whaling Voyages Sailing from American Ports (New Bedford Whaling Museum, The Kendall Whaling Museum, Ten Pound Island Book Co., 2001). [19] Ibid. [20] Information from Table 3 in Peter J. Coleman, The Transformation of Rhode Island, 1790-1860 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1963), 64. [21] Coleman, Transformation of Rhode Island, 63-64. [22] Ibid., 64. [23] Pesch et al., Ecological History of Greenwich Bay, 12. [24] “Whaling,” Tiverton Historical Society, at https://tivertonhistory.wordpress.com/whaling/. [25] For the whaling business, see Coleman, Transformation of Rhode Island, 62-63. [26] For Rhode Island slave trading in colonial times, see Christian McBurney, An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2022), 10-13 and notes accompanying the text 48 and 50. [27] “Warren, the Slave Trade, and Enslavement,” Warren Preservation Society, at http://www.preservewarren.org/p/warren-250th-anniversary-book.html. [28] Hayes, “Warren Whaling Ship Wreck found in Argentina?” [29] James Nanos, “Whales are Dying,” Boston Globe, Oct. 8, 2022.