Long-simmering tensions in southeastern New England over land and the mistreatment of Indigenous people finally exploded into all-out conflict in June 1675. King Philip’s War, as it became known, began in the town of Swansea between the Wampanoag and the colony of Plymouth. The conflict quickly spread beyond Plymouth into the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts by late August 1675 and into Maine in early September, as other native tribes sided with Metacom (King Phillip), the chief sachem of the Wampanoag.

Though their intent was to remain neutral, the Narragansetts were confronted by Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonists in July of that year and forced to sign a treaty promising their neutrality. In July 1675, Connecticut also “garrisoned soldiers conscripted from Stonington and New London, and perhaps Pequot Indian guides, at Bull’s house,” essentially taking control of Pettaquamscutt from Bull and the other Rhode Island residents there.

By October what little trust there was between the English and the Narragansetts had broken down, and most of the settlers at Pettaquamscutt fled from their precarious location in the Narragansett Country to seek safety in Newport. Jireh Bull evacuated his family to Aquidneck in July, and though he stayed longer to work to keep the peace, by October he too had left for Newport. Though Bull continued to negotiate between both sides even after he retreated over the bay, the Narragansett and the English began preparing for confrontation.[1]

Planning for a preemptive strike against the Narragansetts, the United Colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts and Connecticut chose Wickford as an advance base since it was proximate to the Narragansett’s winter quarters. Located within a day’s sail of Portsmouth, Newport, Rehoboth, and New London, Wickford’s harbor could receive necessary supplies for an army potentially numbering in the thousands. Richard’s Smith’s political connections to Connecticut and long experience dealing with the Narragansetts also made Wickford the logical choice to spearhead the attack into the Narragansett country.

An historic marker located south of the Observation Tower on Route 1 and just before the Middle Bridge. It reads: “A Few Rods West of This Spot Stood the Stone House of JIREH BULL, Burned by the Indians, December 15, 1675.” It was listed in National Register of Historic Places in 1983 (Christian McBurney)

An army of nearly 700 men, led by Plymouth’s Governor Josiah Winslow and Major Samuel Appleton from Massachusetts, arrived in Wickford in mid-December 1675. Another force of about 450 arrived from New London, Connecticut, commanded by Major Robert Treat, and planned to converge with Winslow’s army at Pettaquamscutt before marching west and attacking the tribe’s winter fort in the Great Swamp (two miles west of present day Kingston). On December 16, Treat arrived at Jireh Bull’s to discover the trading post along with the rest of the settlement had been destroyed by the Narragansetts, probably the day before. Its fifteen defenders (or seventeen; accounts vary whether two white settlers managed to escape) were killed and the rest of Pettaquamscutt destroyed. On December 19, 1675, Governor Winslow led the forces from Plymouth and Massachusetts to rendezvous with Treat’s men, and then marched the six miles from the ruins of Pettaquamscutt into the Great Swamp. There the armies of the United Colonies engaged the Narragansetts in a hard-fought battle at their winter fort, killing at least 200 warriors and massacring hundreds of women and children after setting the settlement on fire. The soldiers of the United Colonies, in the snow and without any rations (they had burned all the food of the Narragansetts) returned to Wickford on December 20 to rest and regroup. In late December the United Colonies marched from Wickford to attack the sachem “Ponham’s village near Warwick” and destroyed all the native houses there.”[2]

Pettaquamscutt was only the first of Rhode Island’s mainland settlements to face the wrath of the Narragansetts. Wickford proved to be an unsuitable headquarters for the United Colonies’ military operations, since it lacked hospital facilities and sufficient supplies to maintain hundreds of soldiers. When the main Narragansett force moved from South and North Kingstown to the north in January, Governor Winslow followed them, taking most of the troops in Wickford to give chase. In February the small garrison left to protect the settlement was withdrawn as well.

Sometime in the first half of March, the abandoned settlement at Cocumscussoc met the same fate as Pettaquamscutt, and Richard Smith’s trading post was partially burned down. On March 16, 1676, Wampanoag and Narragansett warriors beset Warwick, and on March 19 what was left still standing in Wickford and Warwick was destroyed. A week later Providence was next. Between March 26 and March 29 it too was destroyed, as Roger Williams helplessly looked on.[3]

Soon after, the theater of war shifted from Rhode Island and the fortunes of war turned against the Algonquians. In April the Narragansett sachem Canonchet was captured at Stonington and executed; in May the surviving sachems of the Narragansetts began to sue for peace. On August 11, 1676, Metacom was surrounded and killed at Mount Hope. With his death the Native cause lost its primary architect. Now that victory was at hand in southern New England, the English meted out retribution, executing Natives (including some who had been pardoned), massacring others who had surrendered peaceably, and selling hundreds into slavery in the Caribbean. Meanwhile, the war raged on in northern New England for another year.[4]

The war completely transformed the Narragansett country. Through almost no effort on their part, in a matter of a few months, Rhode Islanders suddenly found that the powerful tribe they had settled amongst was forever broken as a military force (though the Narragansett people were neither eradicated nor entirely vanquished). Across southern New England, it has been estimated that the numbers of Eastern Woodlands tribes relative to the English “decreased by about half, from 25 percent to only about 10 percent of the human population in the region.” For the Narragansetts not killed or who chose not to flee west or north beyond the frontier of English settlement, their economic options grew increasingly limited in the years after the war. Rhode Island passed a law in 1676 forbidding the enslavement of “Indians in this Collony.” But that did not prevent war captives from being “sold into servitude within the colony…on the basis of a sliding scale according to age [with a] maximum term of servitude of thirty years.” Other laws were passed to restrict the Narragansetts from hunting and gathering and generally moving around in their former hinterlands. In 1703, the colony legislature enacted a curfew for all non-whites in public after dark. In 1709 the tribe was relegated to a reservation in the eastern quarter of Westerly that became the town of Charlestown in 1738. By the time South Kingstown was established in 1723, many Narragansetts who still lived there were almost entirely dependent on the English economy as a permanent underclass of debtors, temporary laborers and indentured servants. Others maintained themselves in traditional vocations of warrior, seafarer, and fisherman by enlisting in colonial militias or by working as “mariners and whalers.”[5]

Once the war was over, Rhode Islanders faced the requisite task of rebuilding their settlements, including Pettaquamscutt. Jireh Bull returned and re-established his home before 1683, and by 1687 Pettaquamscutt had recovered sufficiently to support the village’s first tavern.

But by then the town of Kingstown itself was no more. There was a temporary interruption of the status quo. In 1685, upon the accession of James II to the English throne, Edward Randolph was sent to America to establish the Dominion of New England, of which Randolph was the secretary. This consolidation process, which took Massachusetts, Maine, Plymouth, New Hampshire, and the Narragansett country and subsumed them all into a single colony, had actually begun under Charles II upon the successful revocation of the Massachusetts Bay charter in June 1684.[6]

During a meeting at Cocumscussoc in June 1686, Randolph renamed Kingstown, Westerly and Greenwich; Rochester, Haversham, and Bedford respectively. Randolph ordered the organization of a town government for Rochester, complete with a judiciary and a courthouse. However, the new Dominion of New England town of Rochester was as dysfunctional as that of its Rhode Island predecessor, Kingstown. There was little interest in participation from most settlers, and the courthouse had yet to be built when the Dominion in America fell to insurrection after news of the abdication of James II reached Boston in April 1689.

The only positive development during the Dominion period was that Connecticut, facing its own existential crisis, relented in its claims over the Narragansett country. Upon review of Connecticut’s and Rhode Island’s claims over the Narragansett country, Governor Edmund Andros, who had arrived in December 1686 as the Crown’s new governor of the Dominion of New England, decided against the Atherton Company, finding its mortgage to be wholly fraudulent. Andros also ruled that the Rhode Island Charter of 1663 superseded Connecticut’s claims because it was more recent. Once again, English authorities affirmed that the Narragansett country (and the lands that would one day become South Kingstown) was indeed part of Rhode Island and not Connecticut.[7]

Even after the Charter of 1663 was restored by William and Mary in 1692, settlers in Kingstown still did not organize a formal town government or participate in provincial affairs. In the wake of the collapse of the Dominion of New England, there is little record of much government taking place anywhere in the Rhode Island, from the late 1680s well into the 1690s. Only in 1696, two decades after King Philip’s War, a half-dozen years after the collapse of the Dominion of New England, and twenty-two years after the General Assembly legislated the town of Kingstown out of thin air, did settlers choose Wickford as the seat for their new town government. Residents finally held elections, chose a slate of town officers and for the first time sent deputies to the General Assembly.[8]

Despite Wickford’s newfound commitment to Rhode Island, Connecticut soon after reasserted its claims to jurisdiction over King’s County (what is today mostly Washington County). Intercolonial relations reached another nadir when Connecticut voided Rhode Island’s 1700 tax assessment on Kingstown and imprisoned the Rhode Island sheriff in the New London jail when he was sent to collect Kingstown’s taxes. In 1703 another joint commission composed adyof men from Connecticut and Rhode Island reached a settlement concerning jurisdiction over the Narragansett Country. Based on that agreement, Rhode Island moved forward on the question of land titles and town boundaries. In 1706 the boundary between Greenwich and Kingstown, which was never formally located when either town was created, was finally drawn (see Figure 3 below). In October 1707, the General Assembly ordered a survey drawing of the colony and established a committee to hear land claims.[9]

One of the claims committee’s first actions was to recognize Chief Ninigret as the lawful sachem of the Narragansetts. Another committee commenced to purchase most of his lands. These so-called “Vacant Lands” were a vast tract that included much of present-day West Greenwich, Exeter, Richmond, and Hopkinton. The region was officially taken by the committee, which sold most of it off to white colonists within three years. Some settlers found themselves in the objectionable situation of repurchasing land already bought and paid for, just to gain legal title to it. All in all, however, these actions cleared a major obstacle to settlement. The survey and ability to issue land titles bolstered Rhode Island’s claim to the territory, brought stability to the area, and earned the allegiance from those clamoring for legal title for their farms and investments.[10]

Yet in Hartford, the General Court continued to assert its claim to all the lands between Stonington and the shores of Narragansett Bay, rejecting the recommendations of its own men from the 1703 joint commission. In 1720, both colonies turned the matter over to Whitehall, and at long last, in 1726, King George I declared that the eastern boundary of Connecticut was the Pawcatuck River and not Narragansett Bay, undisputedly placing the Narragansett country in Rhode Island once and for all. That most of the lands by then were either owned or occupied by Rhode Islanders, with titles recognized by Rhode Island’s colonial government, no doubt helped push the final decision to place jurisdiction of “Kings County” in the colony of Rhode Island.[11]

Ultimately, the six decades of wrangling over jurisdiction and title to the land had substantial consequences that resulted in a unique settlement pattern and economy for the region. Questions over jurisdiction and legal title to the land had kept demand for tracts low. The low prices, however, did not outweigh the risks in the minds of potential settlers from Connecticut and Massachusetts. As it became increasingly likely that jurisdiction would be awarded to Rhode Island—the land of Quakers, Baptists and other assorted heretics—few upstanding Congregationalists from Connecticut or Massachusetts considered investing or settling there. Most speculators who bought land there were across the bay from nearby Newport, gambling on the land’s future potential value. So unlike the rest of New England, where relatively small tracts were sold to individual families, or granted to communal purchasers who organized themselves around the town commons and a meeting house, the Narragansett country (and what eventually became South Kingstown) was sold off in comparatively large parcels to men who bought the land for speculation and investment.[12]

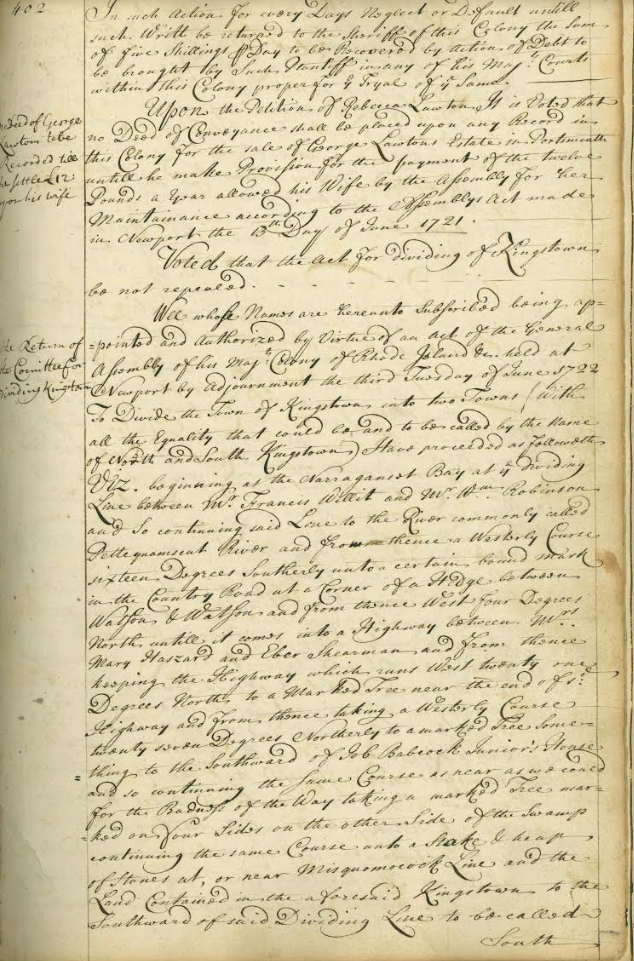

A committee appointed by the General Assembly reports in 1722 on the proposal to divide Kingstown into South and North Kingstown (Rhode Island State Archives)

When Newport’s mercantile ventures took off in the early 18th century, the proprietors (or more often, their sons) seized the opportunity to use their properties in Kingstown to take up commercial agriculture. They converted their substantial landholdings into plantations in the manner of Cocumscussoc, which after its demise as a trading post, became of the region’s first plantation replete with enslaved Africans and indentured Indians. Soon the planters began selling produce on the Atlantic market, particularly to planters in the British Caribbean and in the Southern colonies.

Prosperity attracted settlement. By the first Rhode Island census in 1708, Kingstown’s population reached 1,200. Organizing a local government in 1696 provided the early planters with oversight of roads, fences, inspection of commodities, and control over settlement, key services that “made the land more valuable just by existing.” Based on the tax levies for late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, the decision to finally elect deputies and participate in Rhode Island government paid swift dividends. The community rose quickly from the fifth wealthiest town in 1690 to the second wealthiest only two years after organizing the town government in 1696 (see Table 1). And while the town’s percentage of total tax had nearly doubled from 1690 to 1707, the corresponding increase in wealth generated from produce and rising land values more than compensated the speculators who for the first time paid taxes on their extensive landholdings.[13]

Table 1. Selected Colony Tax Levies on the Town of Kingstown 1690 – 1707

Amount of Kingstown’s Levy in 1690, £27; Total levy for Rhode Island, £300; Rank in Colony, 5; 9% of Total Colony Taxes Assessed.

Amount of Kingstown’s Levy in 1698, £125; Total Levy for Rhode Island, £800; Rank in Colony, 2; 15.63% of Total Colony Taxes Assessed

Amount of Kingstown’s Levy in 1707, £175; Total Levy for Rhode Island, £1,500; Rank in Colony, 2; 17.52% of Total Colony Taxes Assessed, 9%.

Source: Data taken or derived from RICR III, 273 (1690) and 343 (1698), RICR IV, 24 (1707).

By 1720, according to historian Mack E. Thompson, the southern regions of the colony, including Kingstown and Newport, had become distinctly “mercantile” in character. This was in direct contrast, Thompson argues, to the “agrarian” northern regions of the colony. There, “an overwhelming majority of the people were engaged in subsistence agriculture, and commercial activity was relatively unimportant,” where in the Narragansett country (and especially Kingstown) there were “a substantial number of capitalistic farmers.” The first reason for this difference in character was due in part to the region’s fertile and relatively easy topography, as it lay mostly to the south and east of the glacial moraine that had left the rest of Rhode Island to the north and west of present-day South Kingstown and Narragansett increasingly hilly and rocky. The other reason was the aforementioned extensive landholdings of the “Narragansett Planters.” These huge farms (by Rhode Island and New England standards) were mostly worked not by paid laborers but by indentured Narragansetts and enslaved Africans, purchased from Newport, the largest slave-trading port in the thirteen colonies. During the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the southern part of Kingstown was in the initial stages of becoming an agricultural powerhouse and an integral partner in Newport’s Atlantic trade. The region had come a long way since the destruction and malaise of the last quarter of the 1600s, and was soon to experience its first growing pains [14]

Kingstown was a particularly large town, roughly encompassing an area of 172 square miles and consisting of the present-day towns of Exeter, Narragansett, North Kingstown and South Kingstown. The inconvenience of traveling to Wickford, in some cases over two dozen miles over streams and rivers to attend town meetings there, spurred freemen in the increasingly wealthy southern region of Kingstown to petition the General Assembly in June 1722 for a town of their own. This was the first instance the assembly had been asked to fashion a new town out of an existing one (with the possible exception of East Greenwich). The assembly’s response to the petition set important precedents and established a system for the future division of towns in Rhode Island, an increasingly frequent happenstance as the colony’s population swelled over the next half-century.[15]

Kingstown’s division into North and South Kingstown in 1723 was the first of many such divisions in eighteenth-century colonial Rhode Island. According to historian Bruce Daniels:

[b]etween 1723 and 1765, fourteen new towns were formed from territory in towns founded prior to 1678. Six of these were separated from Providence, three from Westerly, two from Kingstown, and one each from Newport, East Greenwich, and Warwick. The old towns were so large physically that residents living in remote areas found it an unacceptable hardship to travel long distances to take part in town political life or to obtain governmental services…In a few cases, economic, social and partisan political factors influenced the decision to become independent towns. In eight cases parent towns gave their approval…but in six they opposed them and [while f]ourteen outlying areas did achieve town status, three other…[petitions were denied by] the General Assembly…

The division of Kingstown in 1723 into North and South Kingstown was the first town division considered by the assembly. In granting the townspeople’s petition, the assembly set forth important precedents to be observed in subsequent deliberations…

One precedent was that the decision to divide Kingstown would be voted on by the deputies from all the towns in the lower house rather than governor and the “at-large” assistants of the upper house. The decision to divide the town was voted on by the deputies from all the towns rather than decided by the assistants of the upper house. The verdict was also delayed one session so the “parent town” of Kingstown could answer the request to separate, and their deputies were allowed to take part in the debate and vote. The reason for separation had to have genuine merit. When Kingstown’s deputies protested the petition, the assembly responded that the town was “very large and full of people so that it is convenient for the ease of inhabitants and dispatching business to divide the town.” Kingstown’s deputies were unable to disprove the validity of that point at the next session, and new charters for both towns were ordered drawn up by the General Assembly on February 26, 1723, which became the incorporation date for South Kingstown. North Kingstown, which included the oldest settled area dating back to Roger Williams’s trading post at Cocumcussoc, kept the original incorporation date of October 28, 1674.

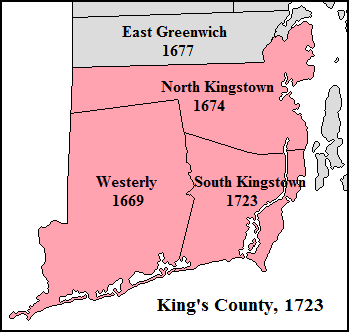

The division of Kingstown brought the total number of towns in Kings County to three – Westerly, North Kingstown, and South Kingstown (see Figure 3). The final, official draft of South Kingstown’s charter was signed, sealed and recorded on April 30, 1723 by Richard Ward, the General Recorder for the General Assembly (he became the governor of the colony of Rhode Island in 1741). A signed copy was inserted into Volume I of the South Kingstown Town Meeting book on pages 31 and 32. This is the document Town Clerk Howard Perry typed out by hand on June 25, 1936.[16]

When Rhode Islanders in other towns complained they were too remote from their town meeting place for convenience or safety and sued for a partition of their towns, the General Assembly considered the same merits of distance, geography, and population density as due cause (or not) for division, just as they had for the residents of South Kingstown. Petitions from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries added other reasons—irreconcilable differences within towns between rural farm areas and industrialized mill villages led to the divisions of towns such as Cumberland and Woonsocket in 1867 and Warwick and West Warwick in 1913. South Kingstown itself was divided in 1888, after residents in what then became the District of Narragansett were stymied in their efforts to build modern infrastructure for their burgeoning resort, with full separation from South Kingstown taking place in 1911.

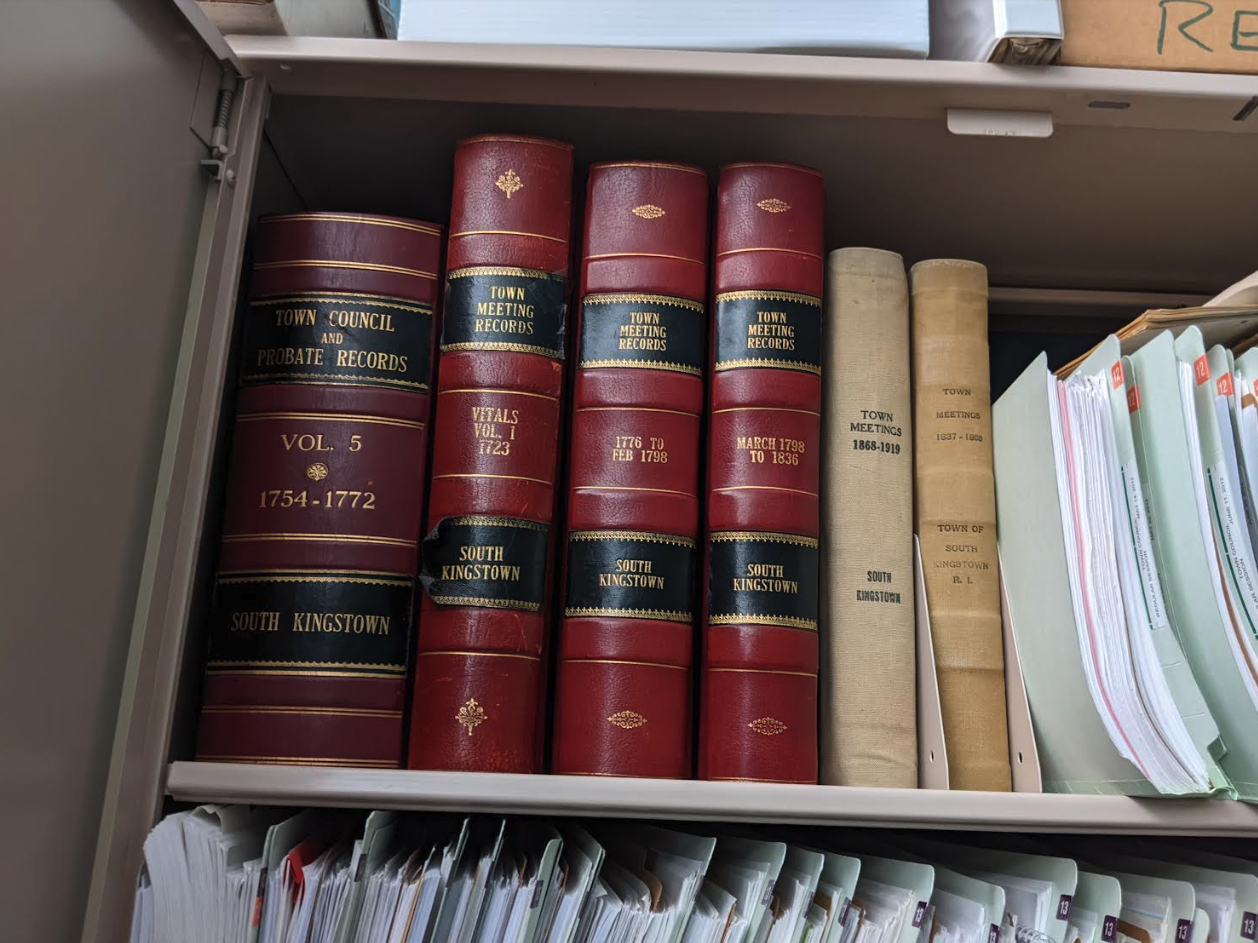

Some of the volumes containing the colonial town records of South Kingstown, including the first volume of Town Meeting records, beginning in 1723. South Kingstown may have the best preserved collection of colonial town records in Rhode Island (Mark Kenneth Gardner)

Though no new towns have been formed from existing ones since Warwick and West Warwick parted ways, South Kingstown’s petition for incorporation was the template by which Rhode Islanders and the General Assembly chartered new towns for nearly two centuries—a legacy worth celebrating. And after its successful incorporation, South Kingstown became one of the most powerful and important towns in Rhode Island, a legacy that endured well into the nineteenth century. The town that started off as Jireh Bull’s trading post and the village of Pettaquamscutt remains the judicial seat of Washington County, and as the home of the University of Rhode Island, South Kingstown has been a center of higher education in the state since it was first chartered as the Rhode Island State Agricultural School in 1888. This year South Kingstown is commemorating its milestone birthday with a year-long celebration of lectures, forums and events – anyone who is interested in learning more should visit http://www.southkingstownri.com/1087/300th-Anniversary.

Happy 300th birthday, South Kingstown!

Notes

[1] Colin A. Porter, “Uncomfortable Consequences”: Colonial Collisions at the Jireh Bull House in Narragansett Country, Rhode Island History, Vol. 72, No. 1 (Spring 2014), 9-11; also see Colin A. Porter, “‘Monuments to a Nation Gone By’: Fortified Houses, King Philip’s War, and the Remaking of a New England Frontier, 1675-1725.” Ph.D. diss. (Brown University, 2013), 105. [2] Porter, “Uncomfortable Consequences,” 9-11; Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War: 120-36; Daniel R. Mandell, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 48-50, 75-78, 86-87; Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougas, King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press, 1999), 255-61. [3] Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk, 137-144, 166; Mandell, King Philip’s War, 94, 100-01; Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage, 1999), 71; “Roger Williams: King Philip’s War,” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (Feb. 26, 2015), accessed at https://www.nps.gov/rowi/learn/historyculture/philipswar.htm [4] Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk, 172-3; Mandell, King Philip’s War, 120-30. [5] Mandell, King Philip’s War, 134; John A. Sainsbury, “Indian Labor in Early Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Sep. 1975), 378-93; John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 16, 36-43; for quote see Mandell, King Philip’s War: 135-36; Porter, “Monuments to a Nation Gone By”: 144; Andrew C. Lipman, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), 203-22. [6] Porter, “Uncomfortable Consequences,” 12-15; Porter, “Monuments to a Nation Gone By,” 131-32; A Preliminary Report On the Excavations at the House of Jireh Bull On Tower Hill in Rhode Island / Issued at the General Court of the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, by Its Governor, Henry Clinton Dexter, Esquire, and the Council of the Society, December 31, 1917 (Providence: E.A. Johnson & Company, 1917), 15. [7] Kathy Bossy et. al., Lost South Kingstown with a History of Ten of Its Early Villages, (Kingston: The Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 10. The exact location of the courthouse planned to be built in Rochester was not specified, but it probably would have been built in Wickford, where the officials of Rochester operated from during the Dominion period. See John Russell Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England. Printed by Order of the General Assembly, Vol. 3 (Providence: A. C. Greene and Brothers, 1856-65), 229 (hereinafter RICR III); see also David S. Lovejoy, Rhode Island Politics and the American Revolution, 1760-1776 (Providence: Brown University Press, 1958, 1969), 202; James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 56-58. [8] James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 93-94, 100. [9] Christian M. McBurney, “The Rise and Decline of the South Kingstown Planters, 1660-1783,” BA thesis (Brown University, 1981), 18; R. H. Howard and Henry E. Crocker, eds., A History of New England: Containing Historical and Descriptive Sketches of the Counties, Cities and Principal Towns of the Six New England States, Including, in Its List of Contributors, More Than Sixty Literary Men and Women, Representing Every County in New England (Boston: Crocker & Co., 1881), 446; John Russell Bartlett, Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England. Printed by Order of the General Assembly, Vol. 4 (Providence: A. C. Greene and Brothers, 1856-65), 31-32 (hereafter referred to as RICR IV). [10] James, Colonial Metamorphosis, 142; RICR IV, 35-36, 44, 50-51, 61-66. [11] Carl R. Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland; The Story of Cocumscussoc, Mirror of Colonial Rhode Island (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1971), 49. [12] Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland, 140-142; McBurney, “Rise and Decline,” 29, 32-33, 36-39. [13] Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland, 25, 58-60. Using the figures from the 1708 census, Kingstown’s population density had by then reached nearly seven persons per square mile. Edwin M. Snow, ed., Report upon the census of Rhode Island, 1865: with the statistics of the population, agriculture, fisheries and manufactures of the state (Providence: Providence Press Company, 1867), xxxii; Nancy Burns, The Formation of American Local Governments: Private Values in Public Institutions (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). 45. [14] Mack E. Thompson, “The Ward-Hopkins Controversy and the American Revolution in Rhode Island: An Interpretation,” William and Mary Quarterly , Vol. 16, No. 3 (July 1959), 364. [15] East Greenwich was established the year after King Phillip’s War in 1677 as a 5,000 acre “tract of land in some convenient place in the Narragansett country…for the accomdatinge of soe many of the inhabitants of this Collony as stand in need of land.” The new town (which at that time also included present-day West Greenwich) was to “have all such Immunities, Privilidges, and Powers as other Towns in this Colony.” Rhode Island Colonial Records, Vol. II (Rhode Island State Archives), 587-588. While technically the tract for East Greenwich was taken from Kingstown, the town of Kingstown at that time existed almost entirely on paper, having been established in 1674 largely for the purpose of “obstructinge Connecticutt Collony from useinge jurisdiction in the Narragansett country.” Ibid, 525. This account of the founding of Kingstown is at odds with the official reason given in Rhode Island’s first set of printed laws in 1719, in the Rhode Island State Archives, which reason was that it had been requested in a petition of inhabitants. This revisionism was probably an effort by the General Assembly to try to “look better” to Whitehall officials who were both reviewing Rhode Island’s long-awaited set of printed laws and Rhode Island’s claims over the Narragansett Country. The explanation given in 1674, that Kingstown was founded for political and jurisdictional reasons rather than at the behest of the residents, is the more believable account. Regarding the society and economy of the Narragansett Planters, see Tim Cranston, “The Narragansett Planters: Commercial Agriculture In Colonial South County,” smallstatebighistory.com (Jan. 13, 2018), http://smallstatebighistory.com/narragansett-planters-commercial-agriculture-colonial-south-county; and Christian McBurney, “The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, Volume 45, Number 3 (August I986), available online at http://www.rihs.org/assetts/files/publications/1986_Aug.pdf. [16] Rhode Island Laws, 1719 (Rhode Island State Archives), 28. Also see Rhode Island Laws, 1730 (Rhode Island State Archives), 126; Bruce C. Daniels Dissent and Conformity on Narragansett Bay: The Colonial Rhode Island Town (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1983), 34 (quoted material). Note that North Kingstown was further divided at the March 1742 General Assembly when the western portion of the town was made the town of Exeter. See Rhode Island Laws, 1742 (Rhode Island Archives), 256-257. For the career of Richard Ward, see John Osborne Austin, Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island (1887): 407.Map Credits

Figure 3. Map of King’s County, 1723, by Mark Kenneth Gardner.

Original Map Files for Figure 3: File, S Kingstown RI lg.PNG by VulcanTrekkie45

<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:S_Kingstown_RI_lg.PNG>

These works are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, made available by the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>.

Boundaries of towns based on Sydney V. James, Colonial Rhode Island: A History, 140.