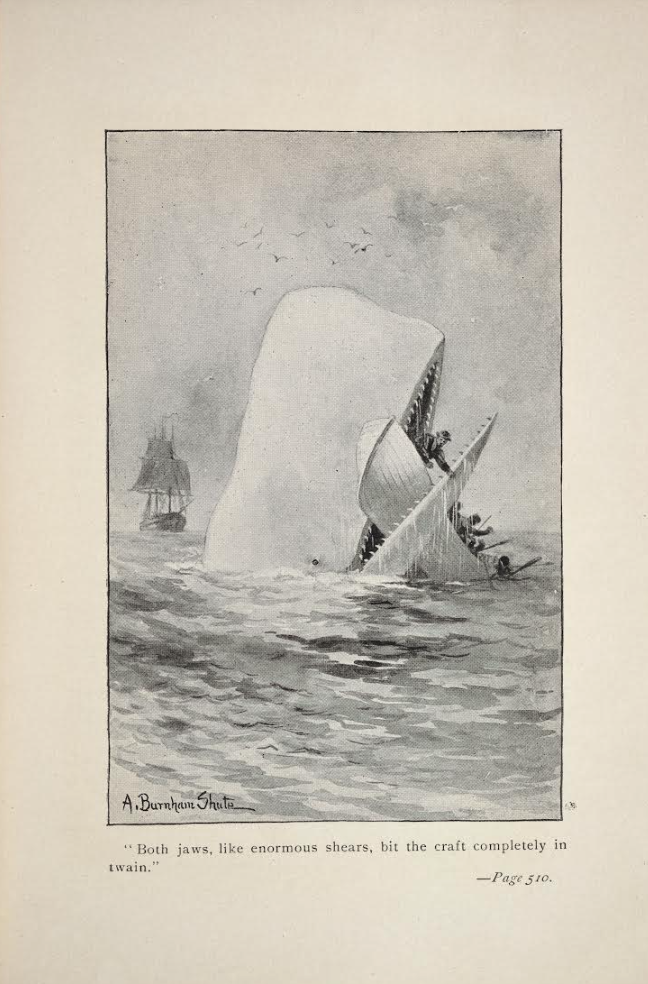

Many readers are familiar with Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick, in which a great white sperm whale stoves a New Bedford whaling ship. Readers may also be familiar that the novel was based on the true story of the Nantucket whaler Essex, which was slammed into and sunk by a sperm whale in the Pacific . The sinking was followed by a harrowing voyage of survival by the crew members in small whaleboats. Nathaniel Philbrick wrote about these adventures in his wonderful 2000 book, In the Heart of the Sea, The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex. First mate Owen Chase, one of eight survivors, recorded the events in his 1821 Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex. (Chase was the main character in the movie as well).

A Newport whaling captain, on a different voyage, underwent a similar adventure—just three months before the publication in the United States of Moby Dick. The captain was John Scott Deblois of Newport, Rhode Island. The one difference was that the surviving crew members did not spend as much time in small whaleboats and therefore did not have to resort to cannibalism to survive as did the sailors from the Essex. At Deblois’s death, the Newport Mercury wrote that the account of the whale’s stoving Deblois’s whaling ship was “well known in every corner of the world.”

This story was nicely summarized in a previous article on this website, “Dirty Work, Clean Money: The Life of Whaling Ship Captain John Deblois and his Wife Henrietta,” by Ingrid Peters And Elizabeth Sulock (http://smallstatebighistory.com/dirty-work-clean-money-the-life-of-whaling-ship-captain-john-deblois-his-wife-henrietta/). But the article by Peters and Sulock has a broad outlook of the lives of the Deblois spouses as a team. This article focuses on details of the whale-stoving episode, relying on Captain Deblois’s own words.

Captain Deblois, born in Newport in 1816, began his whaling career in December 1833, sailing on the Audley Clarke’s first voyage, under Captain Joseph Paddock. The whaler returned to his home port in Newport in June 1837. He next sailed on a whaler from Newport, the Martha, Captain Oliver Potter, which departed Newport in October 1837 and returned in late April 1841. Unsuccessful at obtaining a position as an officer on board a whaler from Newport, he went to Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and secured the post of third mate on board the whaler Isabella, which departed its home port in August 1841 and arrived back there in May 1845. On October 2, 1845, Deblois married Henrietta Tew of Newport. A month later he sailed as first officer on board the whaler Ann Alexander out of New Bedford and arrived back there four years later.

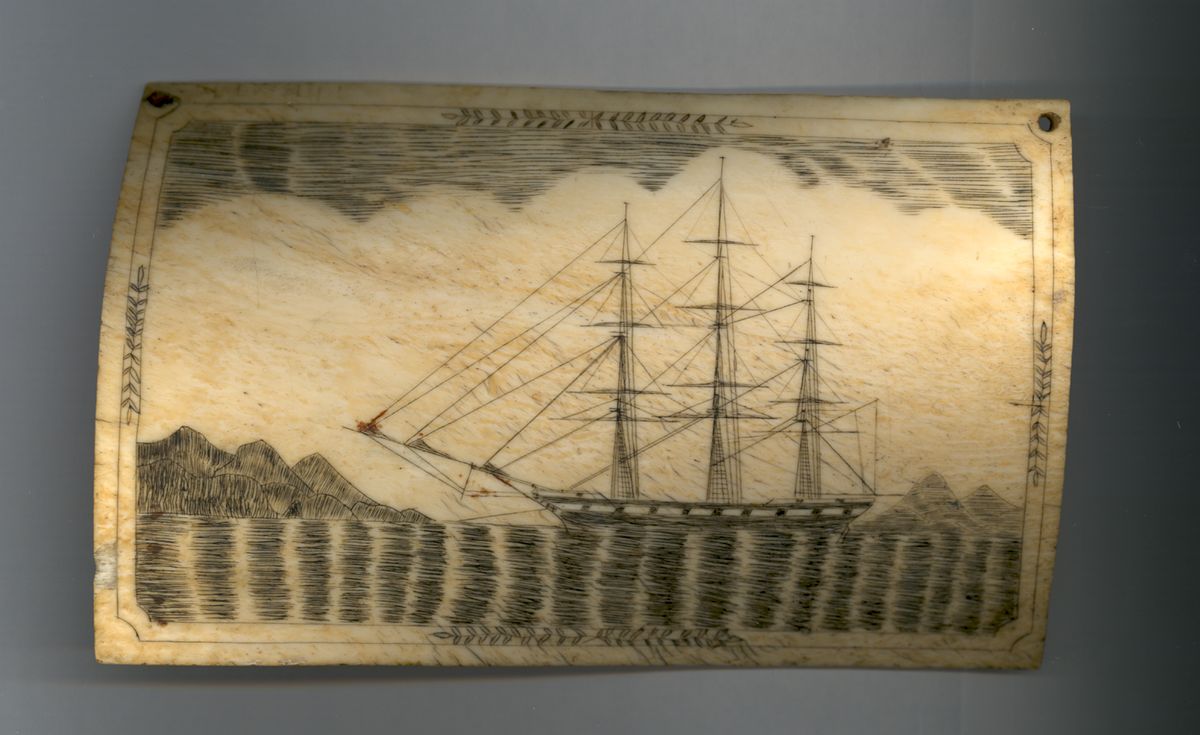

Deblois finally secured a position as captain of a whale ship. It was the Ann Alexander, again out of New Bedford. The ship was owned and fitted out by George and Matthew Howland of New Bedford. As was common with other Quaker whaling investors, the Howlands did not procure insurance for this voyage. Deblois took along with him jewelry, tobacco and other items to trade on the voyage; he too declined to obtain insurance, despite the fact that the items represented most of his wealth at the time.

Deblois’s first mate on the Ann Alexander was Joseph Greene of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Deblois called him the “smartest whaleman I ever saw.”

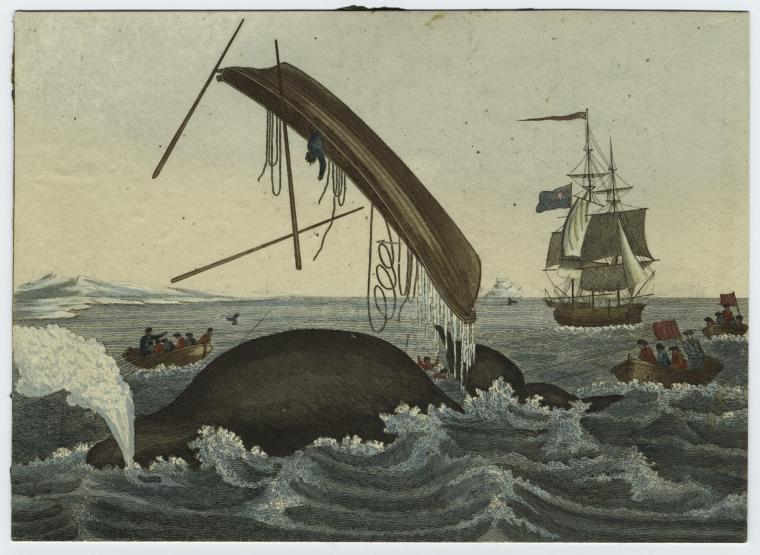

The Ann Alexander departed New Bedford on June 1, 1850 and headed south. Off the River Platte, which currently forms part of the border between Argentina and Uruguay and empties into the Atlantic Ocean, the crew of the Ann Alexander took several whales. This was somewhat fortunate to have taken a few whales before having to sail around the tip of South American at Cape Horn.

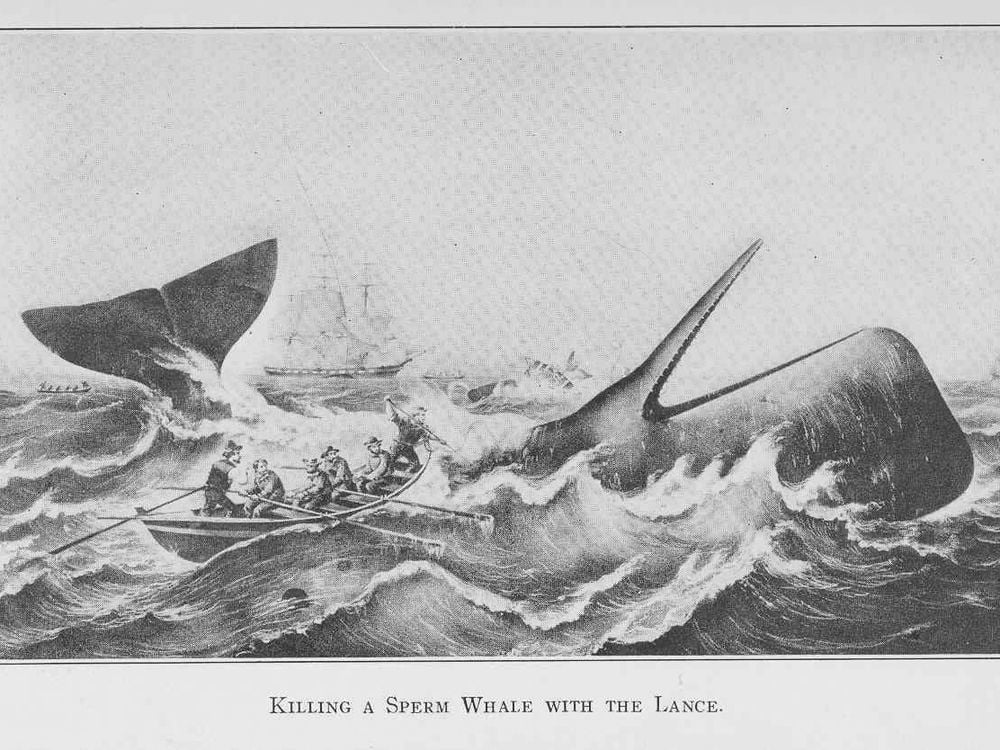

When still in the River Platte, Deblois met his first “fighting whale.” After seeing some sperm whales frolicking behind his ship, Deblois ordered two small whaleboats lowered. One he commanded and the other was led by Greene. When Deblois’s boat was about one-quarter mile from the ship, Deblois struck a sperm whale with a harpoon. Rather than swimming for the deep water, as was common with harpooned whales, this one turned about and smashed Deblois’s boat in two pieces. Suddenly, Deblois and his five crew members were swimming in the ocean, trying to hold on to wooden remains of the destroyed whaleboat.

Deblois saw Greene in the other whaleboat approaching him. Deblois yelled out to his wet crew members, “Boys, can you hold on and let the mate strike that whale?” “Aye, aye, sir,” was the response from all of the swimmers. When the first mate arrived and asked if Deblois wanted to be picked up, Deblois responded, “Never mind me, get the whale! But look out for him, he’s a cunning one.”

The first mate then struck the whale with a harpoon, but a short time later, the whale also smashed his whaleboat. There were now twelve sailors in the ocean. The Ann Alexander was still a quarter mile away. The second mate on board the Ann Alexander had seen the action and lowered a boat to rescue the wet sailors. Deblois also signaled the Ann Alexander, but it did not maneuver correctly, and it sped past the men. Eventually, the second mate’s whaleboat arrived and picked up all the men and returned to their ship.

Deblois outfitted a new small whaleboat with two more harpoons. Greene was desperate to head out again for the same whale and Deblois consented. The first mate got close to the whale, which then sped away out of sight. But then the whale turned around and headed for Greene’s boat, its body half out of the water. Greene did not flinch and hurled the two harpoons successfully at the whale, which soon spouted thick blood and died.

Deblois guided the Ann Alexander around Cape Horn, surviving a fierce gale. Stopping at the Galapagos Islands, his men seized sixty turtles and brought them on board his ship. Each turtle could be kept alive until it was time for it to be eaten by the crew.

In the offshore whale hunting grounds in the Pacific Ocean, on August 28, 1851, a large sperm whale was spotted some five miles away. Again, Deblois and his first mate, Joseph Greene, commanded small whaleboats that headed for the mammoth whale. Greene struck the whale first with his harpoon. This enraged the whale, which turned about and sped at Greene’s boat in an attempt to smash it, but the whale missed. The whale then tried to destroy Deblois’s whaleboat but also missed.

The stricken whale next succeeded in smashing Greene’s boat to pieces. Deblois recalled that in an instant it [Greene’s whaleboat] was “crushed like so much paper in his mighty jaws.” Then “the whale rushed through the wrecked boat two or three times, crushing the largest pieces left, in the wildest fury. The men were thrown hither and tither into the water, and climbing on the broken boat, were again dashed from it. Two men were thrown fully twenty feet into the air by a vicious lunge of the whale.”

Fortunately, none of the seamen was killed. Deblois picked the men up and had them placed in his small whaleboat. Greene then came by in his small whaleboat and the men were divided, nine into each boat.

The whale turned aggressive again, attacking and destroying Greene’s boat. Deblois went to work picking up men in the ocean a second time. Soon there were eighteen men in his boat in heavy seas and with a mad while still in striking distance.

Suddenly, the whale again made for Deblois’s boat, but missed it. Had he destroyed it, Deblois thought, all of the men in it would have perished, because Deblois did not think the men left behind on the Ann Alexander could see the surviving, crowded whaleboat.

Deblois’s relief from the narrow escape was short-lived. Deblois reached the Ann Alexander and deposited the men on board the ship. But seeing the same whale just two miles off, Deblois lowered another two whaleboats to continue with the chase, one commanded by himself and the other by Greene, but the whale was elusive.

After Deblois had returned to the Ann Alexander, the whale approached the vessel. Deblois, from the bow of the ship, hurled a second harpoon into the whale. But at the same time, the whale ran into the Ann Alexander, knocking Deblois off his feet. Deblois checked below, but fortunately the blow did not leave a hole in the boat.

Undaunted, Deblois followed the whale with the Ann Alexander. The whale got close enough to the stern of the ship that Deblois was able to hurl a harpoon that became embedded in the head of the whale. It was the second harpoon embedded in the whale. Because the captain was worried that the rope from the harpoon could break the ship’s rudder, he cut the rope to the second harpoon. The whale, refusing to die, swam away.

Deblois was excited that he had the opportunity to finally kill this injured “fighting whale.” He asked the whalemen to lower and man two more boats to chase the whale and finish off the stricken whale, but no one agreed to man a boat. They all feared their small boats would be again destroyed. (In one entry, Deblois said that Joseph Greene declined as well, but in a later, possibly corrected entry, Deblois wrote that only the men declined and not Greene. Deblois called Greene a courageous man.)

Deblois continued his efforts to find and kill the whale from the Ann Alexander. With only a quarter hour left of sunlight, the captain began to lose hope of finding the whale. He also felt defeated. As he recalled, “I had lost two boats, two lines, some of the men were hurt pretty badly, and we had worked all day for nothing.”

Just as Deblois was about to give the order to break off the chase, he saw a shadow out of the corner of his eye. At this moment, “the whale again struck the ship a terrible blow that shook” the ship “from stem to stern.” “The destroying monster,” as Deblois called it, “had hurled himself against the bow four feet from the keel . . . .” The captain rushed below and saw and heard water rushing into the ship’s holds. He immediately realized that the ship was “gone” and beyond repair. Deblois gave orders to lower the two remaining small whaleboats and to abandon ship.

Deblois then described how he bucked up the spirits of his men:

I found the men thoroughly demoralized and despairing. Their first salutation was, “Where is the nearest land?” I replied, “The Marquesas Islands, 2,000 miles off.” “Let us go right there,” [replied the men] and they put up the mast. “Men,” I said firmly, “do you want your own way or do you want me to advise you?” “We’ll obey you,” they exclaimed. Then I asked them, “who can go six weeks with nothing to eat or drink, and nothing to navigate with? There is plenty in the ship; let us stay and get something to eat.”

The men agreed to follow Deblois’s orders. At that point, both the ship and the second boat, manned by the second mate, were not in sight. The men in both boats spent their first miserable night in them.

In the morning, the men in Deblois’s boat saw both the wrecked ship and the second whaleboat. The men in each whaleboat, 25 in all, congratulated each other for surviving so far. Thirteen men were placed in one boat commanded by the second mate, twelve in the other commanded by Deblois.

At the shipwreck, Deblois saw his trunk floating nearby in the water. Even though it had $975 of gold in it and his other possessions, the captain let it go. If he grabbed that, the other sailors would want to waste time searching for their possessions.

Deblois jumped into the sea and climbed into his ship; eventually, the first mate and sixteen other sailors joined him. Deblois knew where the bread was packed below-decks, but because of the seawater, the bread could not be accessed from below-decks. Instead, Deblois had the top deck boards sawed at the place where he thought the bread would be. In this manner, two barrels of bread were brought out, as well as some corn and other foodstuffs. A few freshwater casks were obtained. While this salvage operation was underway, waves broke over the heads of the sailors.

Deblois decided that more work on the ship would exhaust the men further to little benefit. He ordered the men into the small boats to start their journey to land.

Deblois recalled that most of the men wanted the two boats to stick together, but Deblois disagreed. He thought that if one of the boats sailed faster than the other, it would provide more chance to be spotted by a passing ship. Meanwhile, the boats could plan to take the same course, so that if one were rescued, the other could be too eventually.

Both boats spent a second night at sea. On Deblois’s boat, the sailors clamored for some food, as they had not had any for 48 hours. But Deblois refused, not knowing how far his rations on board could last. The men consented.

“Captain,” blurted out one of the men, “you took too much risk going after that whale.” Other men on board likely felt the same but did not say it out loud. Deblois defended himself, arguing that everyone had the goal of killing the whale and takings its oil.

Other thoughts entered Deblois’s mind at night. He recalled, “My mind was filled with all the stories I had ever heard of shipwrecks, where the famishing men had been often driven to eating their shipmates’ bodies. The recent story of the fearful suffering of the crew of the Essex, who were reduced to these straits and who had even taken lots to see who should die to support the miserable existence of the others, was fresh on my mind.”

Fortunately for Deblois and his men, rescue was not long in coming. In the morning, the second mate’s whaleboat, the faster of the two, moved ahead and was almost out of sight. Deblois stood up in his boat to catch one more glimpse of it and its course, when, to his amazement, he spotted a large sailing vessel. After alerting the other men, Deblois could not tell if the other ship was a merchantman or a whaler. If the latter, it would have a man on the top mast keeping a lookout, increasing the odds that one of the two small boats would be seen. If the ship was a merchantman, it likely would not have a lookout, therefore considerably reducing the odds that the 25 sailors would be rescued. To Deblois’s delight, it was a whaling vessel.

Deblois recalled, “To our inexpressible relief and joy,” the strange ship changed its course and headed for the second mate’s boat. “We were seen! We were saved!” wrote Deblois later. Once the ship stopped at the second boat, Deblois allowed the men on his boat a full ration of fresh water.

The newly arrived ship next picked up Deblois and the men on his boat. As Deblois stepped aboard, he recognized the ship’s captain as an old friend, Captain Richard G. Gibbs. “We rushed into each other’s arms, and it was a full ten minutes before either of us could speak. Then, when I recovered myself, they gave us food and drink, only a little at first, and I told my story.”

Captain Gibbs then explained how he came to the rescue. His ship was the Nantucket of Nantucket. On its way to Japan, the ship had stopped to catch some whales they had spotted. Searching for more whales, a lookout saw the white of one of the two whaleboats and sung out, “There she blows, there she b-l-o-w-s!” Gibbs also went aloft and with his eyeglass spotted the two boats. But he did not see their ship and he soon noticed that each whaleboat had many more men than the six-man crew typically used to chase whales. Recognizing that something was wrong, he ordered his ship to pick up the men in each small whaleboat.

The crew of the Ann Alexander felt they were the beneficiaries of great fortune. The Nantucket had not seen a single ship in days, and yet happened to come across on the open seas the two small whaleboats from the Ann Alexander.

Captain Gibbs decided to sail his ship to the site of the wreck of the Ann Alexander to see if he could salvage anything. Upon arriving at the site, neither Deblois nor any of his crew wanted to get back on the ship. They had had enough of it. A few of Gibbs’s men swam to the wreck and scrambled aboard, but could do little, with waves continuing to crash over the sunken ship’s top deck and with the lower deck underwater. The Ann Alexander was abandoned and left to its fate.

Captain Gibbs dropped off Deblois and his crew at a port in Peru. Deblois began his long journey back to New Bedford and Newport, hitching a ride on a few whalers and making a difficult crossing across the Isthmus of Panama to reach the Atlantic Ocean. Deblois would have a number of successful whaling voyages in his future, but he must have found it difficult upon his return to Newport to face the Howlands in New Bedford, as well as his wife in Newport.

The fate of the “fighting whale” that sunk the Ann Alexander is known. In the May 6, 1854, edition of a Honolulu newspaper, it was reported that the Rebecca Sims of New Bedford, which Deblois and the Ann Alexander had come across just before his engagement with the second fighting whale, took a whale that had in it two harpoons that were identified as coming from the Ann Alexander. According to this account, the whale’s head was very much injured, and pieces of timber were found embedded in the head. Apparently, the whale had been too injured to put up a struggle by the time it came across the Rebecca Sims. The whale yielded about seventy or eighty barrels of sperm oil.

* * * *

Whalers in the age of sail feared sperm whales. However, it was understandable that a sperm whale would become enraged when it was chased by a whale boat and struck with one or more harpoons, or if a member of the whale’s family was killed by whalers. But modern researchers now know that sperm whales are by nature gentle creatures. In a recent segment on the 60 Minutes television show, researchers swam near a giant sperm whale without incident. (The segment also had video of sleeping sperm whales, which sleep in a vertical position for about fifteen minutes before heading down to the depths of the ocean to catch more squid.) Fortunately, sperm whales are a protected species today.

Sources

For John Deblois’s background, see “Capt. John S. Deblois,” Newport Mercury, Dec. 5, 1885, p. 1 (Deblois’s obituary) and the article previously published on this website, “Dirty Work, Clean Money: The Life of Whaling Ship Captain John Deblois and his Wife Henrietta,” by Ingrid Peters And Elizabeth Sulock (http://smallstatebighistory.com/dirty-work-clean-money-the-life-of-whaling-ship-captain-john-deblois-his-wife-henrietta/).

For John Deblois’s recollections of the failed voyage of the Ann Alexander, see the multi-part series in the Newport Mercury, titled “A Fighting Whale’s Triumph,” on the following dates: Nov. 30, 1918, p. 8; Dec. 14, 1918, p. 8; Jan. 4, 1919, p.8; Jan. 18, 1919, p. 8; and Feb. 1, 1919, p. 8.

For the fate of the fighting whale, as well as more information on Deblois’s background, see “A Newport Whaling Master,” Newport Mercury, May 10, 1884, p. 7.