While tiny Rhode Island contributed her fair share of men to serve in the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps during World War I, only one organized unit of Rhode Islanders served in the conflict. The First Battalion of the 103rd Field Artillery Regiment was composed almost entirely of Rhode Islanders. The men who went to war in 1917 wearing olive drab coats, steel helmets, and gas masks were carrying on the proud tradition of Rhode Island artillerymen that began in the woods of rural Rhode Island during the Dorr Rebellion, was forged in blood during the Civil War, intensified during jungle combat in the South Pacific in World War II, and continues to this day with service in the deserts of Iraq and Afghanistan during the War on Terror.

The 103rd had its origins in the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery (PMCA), a militia unit that was founded in 1801 to protect Providence shipping interests during the Barbary Pirate Wars. The corps moved to a land based organization in the 1830s and became renowned for its pioneering use of “flying artillery.” Using small cannons drawn by horses, the PMCA put on demonstrations throughout New England showing their ability to provide pinpoint suppressing fire. The corps saw action in June of 1842 at Acotes Hill, in Chepachet, RI during the Dorr Rebellion. For the next twenty years, the PMCA became a bastion for the social elite of Rhode Island, holding parties and excursions, while also practicing the “scientific art” of field artillery drill. William Sprague, a wealthy textile owner poured thousands of his own dollars into the unit that was admired and copied by many in the North.

When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, the PMCA was ready. On April 18, 1861 amid tens of thousands of well-wishers, the men from Rhode Island left for the war. They were the first Northern militia battery to leave for the front, and became the very first battery in the history of the United States Army to be equipped with rifled cannons. The PMCA went on to recruit nine more batteries of light artillery for the Union war effort and became known as the “Mother of Batteries.” Eight of them formed the First Rhode Island Light Artillery Regiment, which under the command of Colonel Charles H. Tompkins became known as the finest regiment of artillery in the Union Army. The men from Rhode Island served in every battle with the Army of the Potomac from Bull Run to Appomattox, especially distinguishing themselves at Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. Nine soldiers from the regiment were awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism on the battlefield. Additional units also served in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Indeed, General Winfield Scott Hancock was known to quip that he would not begin an engagement until a Rhode Island battery was on the field.

After the Civil War, the PMCA resumed its status as a unit of the Rhode Island Militia, attending summer camp annually at Quonset Point. The unit, now officially designated as “Battery A” was called out in 1898 for the Spanish-American War, but never left the state. Throughout the early 1900s, after the passage of the Dick Act, which professionalized the National Guard, the unit continued to refine its drill, receiving new cannon and several inventive young officers who transformed the unit into an elite fighting force. In 1916, the battery was sent to El Paso during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. During a test of their proficiency, Rhode Island Battery A outscored every other unit in the corps, including those of the Regular Army. It was with these traditions, and experience that the men from Rhode Island prepared to go to war against Germany.

In the summer of 1914 war on a grand scale broke out in Europe as Germany battled its way into France, which resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties on both sides in places such as Flanders and the Somme. Despite American outrage over the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, President Woodrow Wilson held firmly to his policy of neutrality. In 1916, as Battery A rumbled across the prairie dog ridden plains of Texas, only a few members believed they would be sent over to fight in the European war. As late as January 1917, Wilson still hoped to help the Europeans negotiate a peaceful settlement; but those dreams were dashed just weeks later when Germany declared an unlimited submarine campaign.

On April 2, after the deliberate sinking of American ships and an attempt by the Germans to instigate Mexico into action against the United States, with the infamous Zimmerman Note, Wilson could hesitate no longer. The president knew that a new world would come out of this war and he wanted the United States to have a seat in the peace negotiations; thus American soldiers would be committed in their first major overseas action. Arguing that the world must be made safe for democracy, the president asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, which the legislators gave by joint resolution on April 6.

A call for volunteers followed almost immediately, although a draft bill was also in the works. Unlike the uproar national conscription created when it was first introduced in the Civil War, its use in 1917 was generally acceptable to most Americans, including guardsmen who believed it would stimulate volunteerism and help increase their ranks. On May 4, seventy-four men under the command of Capt. Everitte St. John Chaffee, who was about to put on the gold oaks leave of a major, led a parade through Providence in celebration of Rhode Island Independence Day.

Col. Everitte St. John Chafee led the 103rd in World War One. In 1925 he became the first colonel of the Rhode Island State Police (Author’s Collection)

With the declaration of war, Rhode Island began recruiting heavily. Battery A put on displays of drill on the parade ground of the Cranston Street Arsenal, hoping the reaction to the quick, responsive tactics of the field artillery would inspire men to join. Meanwhile, the PMCA Veterans Association did all it could do by hosting a rally on May 8 at the Benefit Street Arsenal. Among the speakers was Capt. Edgar Barker, who had led Battery A during the Spanish-American War. Now his son Harold was the commander of the famed unit. The recent recognition of Battery A’s performance at the Mexican border brought dozens of enthusiastic young men to the enlistment station, at Providence’s central fire house, seeking a spot with the legendary artillery battery. “Then we were ordered to report at the Marine Corps Armory for drill,” recalled one of the enlistees. “Soon, enough men had raised their right hands, thus becoming members of Battery A, to make possible the division of that organization into three batteries.”

Battery A became the nucleus of the regimental headquarters, as well as three firing batteries, “A,” “B,” and “C” of the 103rd Field Artillery; all staffed primary by Rhode Islanders. The regiment formed part of the 51st Field Artillery Brigade of the 26th Division, American Expeditionary Force. The 26th Division became known as the Yankee Division and was manned by New England National Guard units from the six states. Recruits were lured by the mysteries of army life and posters with a picture of an empty saddle and the words “Rhode Island’s Finest has a place for you.” Officers from Battery A with border experience “and other ‘old men’ from the original battery” provided the backbone of the three batteries. As had been the case in the First Rhode Island Light Artillery in the Civil War, the raising of the new units provided the older men an ample opportunity for promotion, in addition to providing a trained cadre of professionals to train the eager volunteers. Among the many names on the rolls were some familiar sounding ones from a half century earlier, including Sgt. Raymer B. Weeden, whose grandfather had led Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, to war in 1861. The new recruits were anxious to have the old soldiers in their new units as they themselves were green and needed to be trained by the soldiers they so admired.

Joining Rhode Island’s batteries in the 103rd were Battery D from New Hampshire, itself a descendent of the legendary First New Hampshire Battery from the Civil War, and Batteries E and F from Connecticut. Troop M, Rhode Island Cavalry, became the Headquarters Company. Some 230 men from Maine and 246 Rhode Island National Guard coast artillerymen helped bring the batteries up to war strength by being transferred to the 103rd. While these men went to war, the soldiers of the Coast Artillery Corps would remain behind to guard Narragansett Bay against feared U-boat attacks.

Not every soldier from the Coast Artillery Regiments could go, however. Pvt. Almase A. Forgue of North Providence had been stationed at Fort Weatherill on coast watching duties when his unit was called to Fort Getty in Jamestown for mobilization. Forgue’s grandson remembered how Forgue was one of the fortunate few to join the elite ranks of the 103rd:

When the U.S. entered the war, the coast artillery units were lined up and 25 men were taken from each artillery unit to go to France. In the count, he was 26. During the unloading and loading of supplies on ships, one of the first 25 in his unit was killed when a load on a crane broke and crushed him. This happened at Fort Getty, on the west side of the island. He became number 25. The horses had to go over two weeks before the unit did, so they could recover from the shipping. My grandfather was a muleskinner on the island, and was then assigned as a wagoner when he became number 25. The officers were in need of a French-speaking interpreter, and he was the only one in his unit who could speak French. Therefore, he went over with the officers and the horses two weeks before the rest of the unit came over. He acted as interpreter when needed.

President Wilson had been calling up units of the National Guard as early as March, but on July 25 he summoned the entire Guard into service. On that day Rhode Island’s three batteries reported at Cranston Street Armory “in prescribed uniform for an indefinite period of field service.”

Shortly before the men left for the new war, they gathered with a contingent of Civil and Spanish-American War veterans to dedicate an elegant bronze plaque on the front wall of the Benefit Street Arsenal to remember those who had before gone from the building to fight the enemies of the United States. The young men of 1917 were very different in appearance from the aged men there to greet them. But they still served the same purpose as defenders of the old flag. Seventyyearold Dr. George B. Peck, a Civil War veteran, former PMCA major, and now a retired medical doctor, stepped forward to address the mixed grouping of veterans before him, but he specifically looked into all of the eyes of the young soldiers before him, who were anxiously awaiting their turn to perform their duty. After telling them of their heritage as Rhode Island artillerymen, Maj. Peck continued:

Comrades of the Olive Drab! I have outlined as briefly as possible the record of your comrades of the red cord of the elder days, comrades all in that we have sworn to obey the orders of our superiors, irrespective. Some of the survivors I see before me. Doubt not that they will follow in your footsteps with the closest attention. Beat their record if you can! Personally I congratulate you on the branch of the service you have selected. Preferable as was the light artillery half a century ago far more to be desired is the field artillery of today. I congratulate you upon the perfection of the armaments with which you have been and will be supplied. I congratulate you upon your officers who have already proven themselves men you may trust. I congratulate you in that you will presumably defend on foreign soil your mothers and your children, your wives and your sweethearts, your homes, your all, therby preserving them from the horrors of Belgium, and France, or Poland, and of Serbia, and of Romania. Especially do I congratulate in that you will take part in overthrowing a slavery as debasing and as cruel as any that ever existed; as debasing in that it enchained not only body but mind and soul; as cruel that it is more reigned. I affirm in this presence I know you will do your best! Whatsoever your footsteps are directed some will succumb to disease. More sure it is a number of us will be missing on your return, for many are living on borrowed time. It, therefore, remaineth for me but to salute you each as an individual–Comrade, Hail! Farewell! and if forever, still forever, fare thee well!

In April of 1861 Lieutenant Governor Samuel Arnold had reminded the men from the PMCA to do their duty to the utmost in the Civil War. Now, over fifty-five years later, George Peck had done the same to yet another generation of young men to leave the Benefit Street Arsenal. The torch had been passed from the generation of men who had saved the United States; now the young men in olive drab had to uphold the sacrifice again “to make the world safe for democracy.”

Church bells rang throughout the city as the green-clad men, staggering under the weight of their barrack bags, climbed up Providence’s steep Waterman Street to the arsenal. After a short drill, the men returned downtown to join all of the state’s National Guard troops in a farewell parade. “Rhode Island had turned out en masse to say farewell to its boys,” recalled one of the new soldiers. “And the boys did well, at least everyone said so, and we were conceited enough to believe that we marched as well any veterans could.”

The following day, the batteries left for Quonset Point, their departure station on Narragansett Bay, an agreeable spot, most of the men decided, to spend the summer. “The Bay was close at hand, Providence was only a few miles away, and as yet neither discipline nor work had become irksome enough to interfere with the men’s spirit.” The men thought they were going to spend a peaceful summer training there. Others were naïve enough to think that the three batteries would not be called for as the war would be over before they could deploy.

By the end of August the three Rhode Island batteries joined the rest of the 103rd Field Artillery in Boxford, Massachusetts, for more training and drill. Without the actual cannons that would be used in France, the men spent most of their time mastering close order drill, learning the routines of service life, and pitching pup tents. Still, the stay in Boxford was not without value, according to the regiment’s historians: “Little, if any, of the knowledge thus acquired was to be used on the Western Front, but the period at Boxford brought officers and men in contact with each other. Already the regiment was beginning to develop that intangible quality which the French call ‘esprit de corps.’” The cannoneers had to learn to work together; if they did not the cannon would not be fired. They had to learn how to grease shells, clean the cannon, and properly sight the weapon. A member of Battery A recalled that “teamwork [was] the essential success of the gun crew.” Many of the Rhode Islanders came from Providence, some from the upper crust of society who had never known how to ride a horse, which were used to pull the cannons and ammunition. Under the watchful eyes of the veterans, all soon became adept at this and the difficult process of becoming a soldier by learning to take orders. One of the main attributes instilled was discipline. Henry Samson related, “At Boxford we began for the first time to realize that we were part of the United States Army—something more than just a body of guardsmen from the State of Rhode Island.”

On September 20, the Second Battalion, which included Batteries C and D and was commanded by Maj. Everitte St. John Chaffee, left Boxford for a critical assignment; transporting some 5,000 horses and mules across the Atlantic, from Newport News, Virginia, to St. Nazaire, France. Not until January 1918 would this battalion join the rest of its regiment. The First and Third battalions, which included the remaining batteries of the 103rd, embarked on the S.S. Baltic at Hoboken, New Jersey, on October 9. Two days later, the Baltic arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where it became the flagship of a nine ship convoy. “All precautions were taken against submarines, the ships proceeding in a zigzag course,” recalled the Battery A historian. “The men were forced to wear lifebelts at all times, and frequent lifeboat drills were held.”

Long periods below deck offered the men ample time for reflection as they headed to battlefields on foreign shores. “Stretched out in our bunks because of the orders to stay below,” recalled one, “we thought of many things, of our homes, of our new lives as soldiers, of our quiet, almost stealthy departure for foreign shores. And then we fell to wondering what the future held in store for us.”

The ships were nearly twenty days in crossing the Atlantic; some of the Rhode Islanders thought they would never see dry land again. After all, it was the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery from whom these men were descended. Despite the weary hours below deck, the men knew that action was sure to come once they landed in Europe. As the convoy neared the Irish coast, three English destroyers met the ships to provide added protection in the submarine-infested waters off Ireland. On October 23, the convoy finally dropped anchor in the Mersey River at Liverpool, England. Less than a week later, after traveling by train to Southampton, the men were once again plying rough and dangerous waters, the English Channel, en route to France.

After two days and nights in a cramped cattle car, the men arrived at Camp de Coëtquidan, an artillery camp in Brittany built by Napoleon in 1804. Indeed the great tactician had once said, “God fights on the side with the best artillery.” The camp, with its stone barracks and extensive artillery range, would be the home of the 103rd for the next three months. The First and Third battalions were already well tuned in the tactics by the time the Second arrived six weeks later. Amusements were few, the nearest village was several miles away, and drills were intense. But many believe the later success of the 103rd was due in large part to the training at Coëtquidan, or “Coqui,” as it was called by the men. “What the artillery manuals call ‘fire discipline,’ that peculiar efficiency of a gun section that determines its value in active operations, can only be acquired by weeks of grueling, monotonous effort in park or on the drill field, “wrote one historian. “That the batteries of the 103rd were able to give such a good account of themselves in the famous offensives of AisneMarne, St. Milhiel and Meuse-Argonne was due in large part to the tireless energy and able leadership of veteran French commissioned and noncommissioned officers who spent day after day at Coëtquidan instructing the gun crews in the mysteries of the ‘service of the piece.’” Despite the efficient training received from the French, the Rhode Islanders had to be watchful. Throughout the conflict both the French and the English tried to assume command of the American Expeditionary Force. Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing was adamant that Americans would serve only under American officers in an American army.

Since their days at Quonset, the men and officers had heard rumors that they were to become a heavy artillery regiment in France and would not be using the three-inch guns that had distinguished them in the light artillery category. Sure enough, several weeks after arriving at Coëtquidan the regiment was issued 155mm SchneiderCruesot howitzers, considered the most sophisticated artillery piece of its time. Each of the six firing batteries received four 1917 models of these howitzers, which had been designed two years earlier by the famous French firm of Schneider et Cie.“[These were] guns that packed a mighty wallop, whose range was nearly seven miles and for which, when properly elevated, ‘dead space’ practically ceased to exist,” noted Capt. William F. Kernan in his history of the 103rd. “They looked heavy and they were heavy, these snub-nosed, bell-mouthed hussies; they made horses and men lather, but once in position, they spoke with an authority not to be denied.” Upon receiving the howitzers, members of Battery C considered them “the best in the world.”

Conditions at Coëtquidan through that long, cold and rainy winter were primitive. Food and fuel were scarce, the barracks were poorly heated and ventilated, and candles provided the only light. “The men kept at their training, conquering their first enemy in France, the mud,” wrote one Rhode Islander. Among the most useful tactics and skills learned were mock battles where the cannoneers would fire blanks to simulate being under fire. In addition, command posts and firing positions were cut out to simulate firing by battery, battalion, and regiment. Here the officers put the practical side of their training to use by being able to learn how to control their batteries in a simulated scenario. Despite these activities, however, the soldiers of the 103rd were growing restless. They knew how to use their howitzers but wanted to put the knowledge and skills to practical use at the front. On February 2, when new English gas masks were issued, there was the sense among the more astute that “something was bound to happen” soon.

Two days later the regiment was on its way to the Western Front. The 103rd, still considered green, was sent first to Chemin-des-Dames, a relatively quiet sector at this time. It was here that the men mastered the “techniques and tactics” of the Western Front, learned largely from the veteran French soldiers who were now well into their third year of war. The Americans admired the French meticulousness and attention to detail, while the French expressed delight over the American’s good humor and energy, qualities that would serve the war weary Allies well in those final crucial encounters with the Germans.

At the end of March, the 103rd was sent to defend the Toul sector, a move that involved an exhausting fifteen day hike through mud and rain. It was here that most people agree the 26th Division, known as the “Yankee Division,” began to prove its mettle. Fred McKenna of Battery A wrote:

In looking back, it becomes more and more clear that in every respect, save that of time, the Toul front was for the Battery its initial fighting front. True, at Soissons [Chemin-desDames] the men performed all their duties with a zeal, a precision and an excellence that was highly lauded by the French commanders. Those duties, nevertheless, were pleasant and free from danger, for there chanced to be during this period but little artillery activity. However, in the Toul Sector, seldom a day passed but that some gas, fatally sweet, painfully injurious, and with a name of about thirty-five letters, contaminated the air. And times without number the dugouts trembled beneath the loud crash of large caliber shells. At Soissons, the men were receiving the finishing touches to their military education; at Toul they were veteran fighters. At Soissons, the Yankee Division was brigaded with the experienced French Army; at Toul, without aid, it held a front of 22 kilometers.

The test was not what many had desired, thinking the life of a soldier to be grand. One Battery A soldier wrote, “There is but little romance in the life of an artillerymen; little of the element of the general helishness [sic] of life that appeals to the artists, correspondents, and fiction writers. But there are exciting moments, and moments of great danger, around the big guns.” This first taste of combat was something that none of the men who had enlisted in the three Rhode Island batteries of the 103rd could ever have imagined. After the war, one soldier from Providence recalled it: “I would not have believed we could have endured it, but it was the knowledge that we were driving the Huns before us which kept us going.”

Major Harold Barker led a battalion in World War One. Two decades later as a brigadier general, he led the 43rd Division Artillery in the South Pacific in World War Two. One of the highest decorated soldiers to ever serve in the 103rd, his awards include 2 Silver Stars, 2 Legions of Merit, a Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, and 5 campaign medals. (Author’s Collection)

But life would get harder for the Yankees long before it got better. On July 15 the Germans launched a general attack along the line. From Toul the division was hurled into “the fire and fury of the ChampagneMarne defensive,” and from there it would move directly into the brutal AisneMarne campaign. Here, the 103rd Field Artillery Regiment was under the command of Col. Pelham D. Glassford, the officer who had been assigned to Battery A as an inspector instructor during its difficult years just a decade earlier. Now he was doing it again with an entire regiment of New England artillerymen. The guns of the regiment kept well to the front, “always on the heels of the infantry.” The Second Battalion was sent into the rat infested trenches for the first time and earned the colorful title of “Glassford’s Trench Mortars,” for the pinpoint precision firepower they delivered for the infantry of the Yankee Division.

Assisting Col. Glassford in his operations was none other than Lt. Col. Everitte St. John Chaffee. “These two men made up a working-fighting team that was hard to beat in such a rapidly changing and highly complicated situation,” noted Capt. William F. Kernan. “They never demanded more of their men than they were willing to undergo themselves and their energy and aggressive spirit, never shown to better advantage than in the Second Battle of the Marne. Desirous of seeing things for themselves, they were continually in the forefront of action and many stories of their utter disregard of danger are still recounted in the Regiment.” The relationship between Glassford and Chaffee was remarkably similar to that between Col. Charles Tompkins and Lt. Col. J. Albert Monroe in the Civil War. Both men had worked in tandem to insure the Rhode Island Light Artillery was a potent force; now that effort was played out again on the Western Front.22

The Second Battle of the Marne in August marked the start of the German retreat and a decisive turn of the tide. Gen. Ferdinand Foch, supreme commander of the Allies, began to believe victory was possible by the fall, but only by striking the Germans a succession of well-timed blows. The nearly two million men in the American Expeditionary Force greatly bolstered the strength of the Allies, who now turned to the Americans to plug the huge gaps in their lines. “The 103rd Field Artillery, blissfully ignorant of the works and ways of the high command, spent the latter part of August in a ‘rest area’ on the Haute Marne,” recalled Capt. Kernan. “Here in the little towns of Latrect and Leugley, amidst the hedgerows and orchards of the Cote d’Or, the war seemed far away and well forgot. The men read and wrote letters, brushed up their French, ate enormous meals washed down with vin ordinaire, took leaves to Paris and returned to boast of their adventures along the boulevards.” The losses in the 103rd had been light to date, with only a few combat casualties. Despite this, the rest was needed and helped to build unit cohesiveness that was invaluable the next time they took the field.

This idyllic and much-needed respite would come to an abrupt end on August 27 at a party given by Glassford for the men. During a performance of the division minstrel show, Glassford suddenly took the stage holding an ominous telegram. “Men,” he said, “we’re off for another fight.” Two hours later the First Battalion was pulling out of Leugley and the populace, stunned and anxious at the sudden departure, “turned out with cheers and tears to see us march away,” wrote a Battery B soldier.

Battery C of the 103rd Field Artillery in action during the Meuse-Argonne offensive (Author’s Collection)

Gen. Foch had assigned the newly formed American field army the mission of defending the Paris-Avricourt railway and the reduction of the St. Mihiel salient. The 26th Division was to be one of fourteen divisions employed in the operation. The assault on the St. Mihiel salient was scheduled to begin at 5:00 a.m. on September 12, but preparation fires were to be put down four hours earlier in torrential rain. Capt. Kernan described it:

With all watches synchronized, a thunderous crash broke through the storm on the stroke of one and a cyclone of bursting shell struck the enemy positions-shrieking, rumbling, screaming, whining, away they went destroying machine gun emplacements, trenches, C.P.’s, barbed wire, as the corporals of the 103rd pulled the lanyards and twirled breech blocks to the tune of the fiercest bombardment the Regiment had as yet put down. This was a Corp’s battle and no mistake about it. Down in the pits the men, full of enthusiasm and too excited to mind fatigue or discomfort, worked with machinelike precision, calling from time to time between explosions the old war cry of the artillery, “Give ’em hell.”

All along the line, the 103rd artillery fired, supporting the attack of the Yankee Division. The soldiers from New England were more than making a name for themselves. One French officer said, “Your Gallant American Division has set us free against the Barbarians.” One of the main reasons for the successful assault was the combined firepower of the three battalions of the 103rd Field Artillery which supported the combined assault from the Yankee Division’s four large infantry regiments.

Within two days, the objectives of this campaign were nearly achieved and by September 16 the whole of the BoisdesRappes had been captured. “The entire success of this first offensive by the American Army greatly stimulated the morale of the Allies and depressed that of the Germans,” noted Capt. Kernan. “Nearly 16,000 prisoners and 443 cannon had been captured, and over 200 square miles of territory, with its remaining French population, had been restored to France. The railroads in the vicinity of St. Mihiel had been freed for the use of the Allies, and the threat of the salient against surrounding territory had been removed.” Only a few months earlier it had been the Germans who had been continuing their relentless push west towards Paris. Now the American Expeditionary Force was beating them back at every turn.

Life on the Western Front was pure misery for the men from Rhode Island. They faced constant dangers each day and night, as the Germans kept up a ruthless bombardment. The soldiers had to live underground to escape the fire above. Trenchfoot was a constant problem caused by the poorly fitted wool and leather uniforms that had not changed much since the Civil War; they disintegrated in the harsh conditions and were not easily replaced. Soldiers were covered with “cooties,” or body lice, while rats ran through the trenches nibbling on everything in sight. Horrible food, such as crackers and “bully beef,” and tainted water added to the misery through disease. Gas was a constant threat as well; no soldier went anywhere without his gas mask always being available. In addition to these threats, aircraft would occasionally bomb and strafe the positions. Camouflage was essential, and much time was spent digging in, while the drivers cared for the horses, many of whom simply weakened and died. It was almost a return to the long days on the siege line at Petersburg, some fifty years earlier. The soldiers of the 103rd had to be on their toes all hours of the day, ready to respond to any threat. Life in France was hell on earth, but the tough men of the Yankee Division were making the difference.

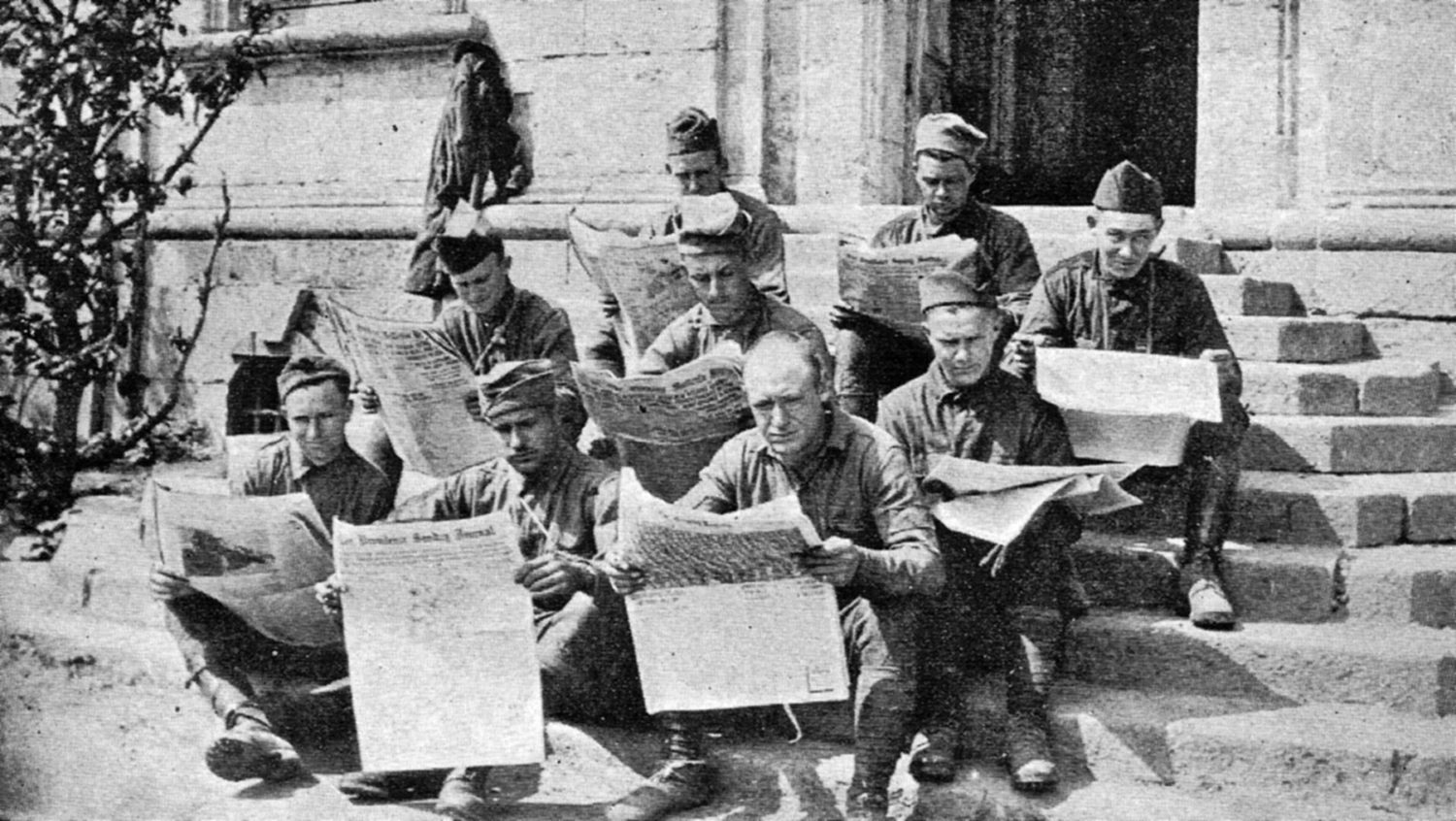

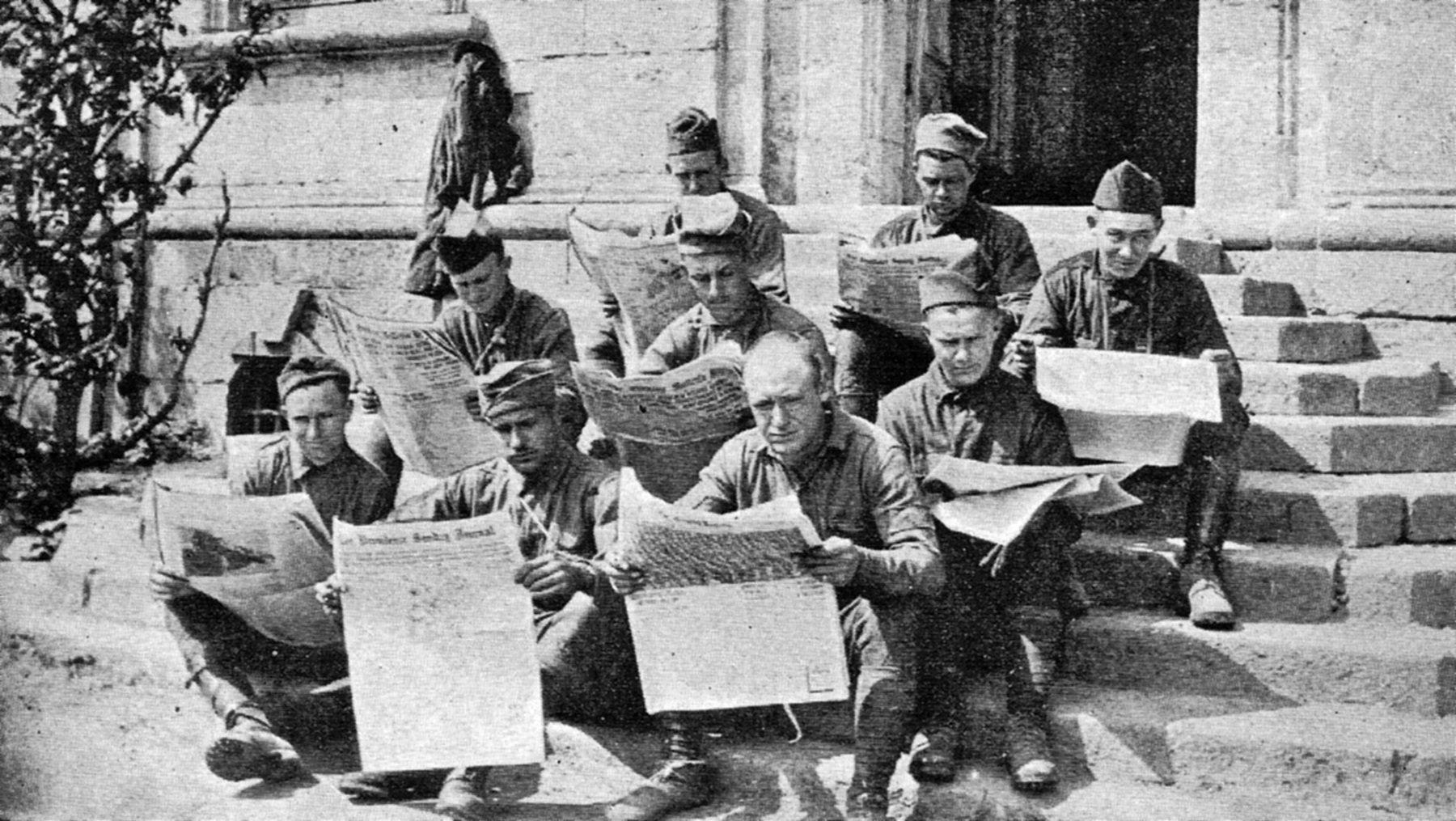

Somewhere in France, soldiers of Battery B stop to read the Providence Journal (Author’s Collection)

Although its mission was accomplished, Foch kept the 26th Division in place to deflect German attention from the Allies’ next and final great offensive, between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest. Until October 17, when the 103rd became actively engaged in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, the artillery batteries did their best to harass the Germans with raids and counterattacks. It was during this time that Maj. Harold R. Barker, now commander of the Second Battalion, invented a game that came to be called “snipe hunting with a 155 howitzer,” which involved relentless harassing and retaliation fire.

With the offensive on the Meuse under way, Foch was increasingly concerned by the slow progress of the right flank of the American First Army, which was hampered by the superior position of the enemy. He turned to the New Englanders for help. The 103rd was placed north of Verdun, terrain the Germans had fought over in 1916 and which they knew well. “A battery, carelessly emplaced or insufficiently camouflaged was a battery lost,” noted Capt. Kernan. Gen. Foch credited the resourcefulness and tactical knowledge of Col. J. Alden Twachtman, now regimental commander, with keeping the batteries from being spotted and enabling them to put down a concentrated bombardment.

With the final campaign heating up around them, the men at the front gave little thought to these distractions. “They had long ago committed to memory the immortal line of Kipling: ‘If you want to win your battles—take and work your blooming guns.’” And that they did. The regiment began an ordeal that would last right up until the Armistice, one that “made the old days on the Toul front and even St. Mihiel seem mild by comparison.” Indeed it was October 24, 1918 that would be the worst day of the war for the 103rd Field Artillery. That night the Germans opened a terrific bombardment on Rhode Island’s Battery C. Several direct hits were scored, and six men were killed. Despite the carnage, the men stood by their cannon and their brothers. Three men of Battery C were among the eight members of the regiment to earn the Distinguished Service Cross, the United States’ second highest military decoration.33

The Meuse-Argonne offensive was taking its toll on the 103rd Field Artillery Regiment, much as it had been with the First Rhode Island Light Artillery during the brutal Overland Campaign of 1864. Despite this toll, the campaign was bringing the Germans to their knees. As was the case in earlier struggles, the artillery in particular was playing a vital role in destroying the enemy positions. One historian wrote, “In the course of the campaign Pershing’s artillerymen fired a tonnage of munitions that exceeded the totals fired by the entire Union Army during the course of the Civil War.” After forty-seven days of nonstop combat, the Rhode Islanders had finally accomplished their mission.

November 11, 1918, found the batteries of the 103rd in position near Beaumont, ready to continue their fire into enemy emplacements. A soldier from Battery B recorded the event:

Then at 9:45 that morning we received news that seemed too good to be true. An armistice had been agreed upon, and we were to stop firing at 11:00. The men went wild. Up until 11:00 we gave Heinie everything we had. On the last shot every member of the firing battery, all the cooks included, as well as a number of officers from G.H.Q. [Gen. Headquarters], helped to pull the long lanyard which had been brought out for the purpose. For a moment there was silence, not a gun to be heard anywhere. Then the men gave vent to their feelings. We joined the French in celebrating. It was a wonderful sight.

In Battery C, the men were doing much the same as those in Battery B. Henry Samson recalled when it was all over: “An awesome silence settled over the sector.”

The initial euphoria of seeing the war finally end quickly dissipated, however, as the men began to suspect they would not be going home anytime soon. Furloughs broke up the monotony of daily drills, but even a weekend in Paris was no match for the warmth of home, hearth and family. After ten grueling months of war, coping with mud, rain, rats, and body lice, and fighting a relentless foe, the men eagerly awaited orders to embark. They would wait more than four months for those orders to come, but on March 31 “packs were made up for the last time on French soil and the men were ferried out to the S.S. Mongolia [which] pointed her nose toward the rosy sunset and the good old United States.”

The Yankee Division received an enormous welcome upon its arrival in Boston and Headquarters Battery, as well as Batteries A, B, and C enjoyed an equally enthusiastic greeting on their return to Providence in April 1919. As had happened fifty-four years earlier in 1865 when the veterans of the First Rhode Island Light Artillery returned from the South. Thousands of Rhode Islanders were there, along with the governor and the old veterans of the PMCA. The cannoneers were showered in gifts of chocolate, candies, and sandwiches. Despite this, many just wanted to get back home and on with their lives. Unlike many National Guard divisions, the 26th had preserved much of its regional character, symbolized by the blue and green “YD,” the Yankee Division, patch worn on the left arm, and it was one of the rare cases in which the artillery had remained with its parent division. Some in the Regular Army continued to dismiss the skill and discipline of the guardsman, but those who had witnessed his work and courage in Europe were truly impressed. After the 102nd Infantry Regiment of the 26th Division advanced into forty German batteries and captured them on February 28, 1918, the colonel commanding the regiment insisted that the American militia had reestablished its reputation: “The American militiaman, when he is properly led, is the finest soldier who ever wore shoe leather.”

The fighting on the Western Front was the most horrific up to that time in world history. Not even the terrible carnage and slaughter of the moonscape of Spotsylvania Court House in 1864 could compare. The officers and men of the 103rd fought with extreme gallantry, but as always, that bravery came at a great cost. The following members of the Rhode Island batteries of the 103rd gave their lives in World War I: Battery A: Capt. Joseph C. Davis, Sgt. Joshua K. Broadhead, Corp. Ernest H. Munroe, Pfc. John E. Benson, Pvt. Fred A. Almquist, Pvt. Dona J. Dugal, Pvt. Carl F. Green, Pvt. Charles E. Jenkins, Pvt. Beverly S. Lake, Pvt. William D. Packer, Pvt. George A. Rieo, and Pvt. Eugene J. St. Amour. Battery B: Lt. Archibald Coats, SSgt. Edgar P. Black, Corp. Ray C. Betherman, Pfc. William J. Brailsford, Pvt. Albert C. Butts, Pvt. Frederick A. Harmon, Pvt. Willie J. Bacon, Pvt. William H. Francis, and Pvt. Harry C. Leeman. Battery C: Sgt. Lawrence E. Redmond, Corp. James Hemphill, Pfc. Lawrence S. Ayer, Pfc. Gaskin P. Williams, Pfc. Boleslaw Osmolski, Pfc. David Paineau, Pfc. Anthony F. Sylvia, Pvt. Edgar H. Greenhaulgh, Pvt. Richard J. Dennis, Pvt. Russell K. Bournce, Pvt. Charles Bacon, Pvt. Wilmer H. Eicke, Pvt. Fred L. Humphreys, Pvt. Henry Becker, Pvt. Jewel B. Rumsey, and Pvt. Albert Payette. “Dulce et Decorum est Pro Patria Morte.”

The men from Rhode Island who had gone to war wearing olive drab rather than the traditional blue again elicited praise from their commanders and comrades. The soldiers from the three Rhode Island batteries of the 103rd were always at the front, working the Schneiders under any weather conditions and battlefield situations. As George Peck had promised before they went “over there,” the men had indeed selected the right branch of the service and had carried on the traditions laid down by their remarkable forefathers. In a testament to the regiment, Gen. Clarence Edwards, the original Yankee Division commander, wrote after the war: “I will recall the fine work of the 103rd Field Artillery with their heavy guns. They were under desperate shelling and almost constant gas, but they kept their nerve and continued their fire, and only stopped at eleven o’clock on the morning of November 11, Armistice Day.”

Several years after the war, the veterans of the 26th Yankee Division raised funds for the memorial chapel to the division built at the Ainse-Marne American Cemetery. The original chapel had been destroyed by the fierce fighting in nearby Belleau Wood. During the peace it was rebuilt by the division and dedicated as a monument to the fallen American soldiers and their French comrades. Of particular note are the names of those 103rd soldiers who lost their lives, which are carved in stone as a lasting memorial of their sacrifice. As the cannoneers of the Civil War had done, the men who fought on the Western Front again banded together after the war to form their veteran’s organization. They had to readjust to civilian life and learn to come and go as they pleased. It was again a trying experience—trying to forget the horrors of trench warfare. On May 30, 1919, Decoration Day, the PMCA held a memorial service at the Benefit Street Arsenal in honor of those who died in the war. In time, plaques inscribed with the battle honors of the Western Front would proudly be emblazoned on shields and hung next to those from the Civil War. Men who served in the regiment on the Western Front became a staple at regimental reunions, telling their old war stories until the final Battery C veteran passed in 1989.

For the first time the gallant artillerymen from Rhode Island had flexed their muscles overseas and had proved to their French and British allies, in addition to their German foe, their fighting prowess. They had been the first New England and National Guard unit to fire in anger in France. Furthermore, the 103rd had spent 284 days on the line. Their epitaph was written by Gen. John H. Sherburne: “Often weary, sleepless, and exhausted, officers and men showed unfailingly a spirit of courage, determination, and cheerfulness typifying the very highest standard of American ideals.” The Rhode Islanders had performed their duty, carried on the tradition of Rhode Island artillery greatness, and performed superbly under fire.

The experience and traditions earned by the 103rd on the Western Front would be used again a quarter century later when the regiment was called out again to serve in the South Pacific as part of the 43rd Division in World War II. General Harold R. Barker and his Rhode Islanders comprising the 103rd and 169th Field Artillery Battalions would earn many accolades fighting the Japanese in the hellish jungles at Guadalcanal, Munda, New Guinea, and in the Philippines. Col. Chaffee became the first superintendent of the Rhode Island State Police in 1925, which numbered many 103rd veterans among its early volunteers. Today the uniforms of the Rhode Island State Troopers are a direct copy of those worn by the men of the 103rd on the Western Front. During the Cold War, the men from Rhode Island served in Germany during the Korean Conflict, and trained relentlessly to maintain the peace during several overseas training missions into the 1980s. The regiment was called up again after the events of September 11, 2001 and has seen combat in Iraq and Afghanistan during the War on Terror. Today the Benefit Street Arsenal in Providence is a military museum devoted to the officers and men of the 103rd Field Artillery Regiment who have lived up to their regimental motto of “Play the Game.”

[Banner image: Somewhere in wartime France, soldiers of Battery B stop to read the Providence Journal (Author’s Collection)]

Sources used:

This article is primarily based on material in Robert Grandchamp, Jane Lancaster, and Cynthia Ferguson, “Rhody Redlegs” A History of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery and the 103d Field Artillery, Rhode Island Army National Guard, 1801-2010 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Publishers, 2011).

The history of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery and it’s modern descendent, the 103rd Field Artillery Regiment are surprisingly detailed. Full regimental histories covering the history of the unit have been written for its participation in the Civil War, Spanish-American War, 1916 Mexican Border Expedition, World War I, World War II, and the War on Terror. Manuscript material covering the history of the PMCA and the 103rd Field Artillery is housed in several repositories in Rhode Island. The Rhode Island Historical Society and Benefit Street Arsenal (owned by the Rhode Island National Guard) both contain important early manuscript materials, while the Rhode Island National Guard Headquarters maintains more current records. There are two regimental museums in Providence, one at the Benefit Street Arsenal, and another at the Armory of Mounted Commands on North Main Street that tell the history of the regiment. Several published sources were essential to this study. Most of these books can be found in the larger libraries of Rhode Island:

These three volumes are essential to understanding the early history and origins of the PMCA.

George B. Peck, Historical Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Memorial Tablet on the Arsenal Benefit Street, Corner of Meeting, Providence, R.I., Thursday, July 19, 1917. Providence: Rhode Island Print. Co., 1917.

Thomas M. Aldrich, The History of Battery A, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. Providence: Snow & Farnham, 1904.

Henry R.W. Stiness, Battery A on the Mexican Border, 1916. Providence: NP, 1916.

After their return from the front, two officers of the regiment wrote the official history of the 103rd which contains excellent information on the regiment, as well as detailed maps:

W.F. Kernan, and Henry Tritton Samson. History of the 103rd Field Artillery (Twenty-Sixth Division, A.E.F.) World War, 1917-1919. Providence: Remington Print. Co, 1930.

While the regimental veteran’s association published the official history of the 103rd in 1930, the soldiers of the three firing batteries from Rhode Island also published detailed histories. These three volumes are very similar to the regimental histories published by the men who served in the First Rhode Island Light Artillery during the Civil War. They contain photographs of the men, images from the battlefield, detailed maps, as well as pertinent personal information.

Fred A. McKenna, Fred A. Battery “A”, 103rd Field Artillery in France. Providence: Livermore & Knight, 1921.

Henry T. Samson, and George C. Hull. The War Story of C Battery, One Hundred and Third U.S. Field Artillery, France 1917-1919. Norwood, MA: Plimpton Press, 1920.

History of Battery B, One Hundred Third Field Artillery Twenty-Sixth Division. Providence: E.L. Freeman, 1922.

As part of the famed 26th Yankee Division, this source was particularly useful to understanding the overall larger picture of how the New Englanders contributed to the fighting in France.

Emerson Gifford Taylor, New England in France, 1917-1919: A History of the Twenty-Sixth Division, U.S.A. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920.

In addition, the local Providence Journal contains a wealth of information on the participation of the officers and men of the 103rd Field Artillery on the Western Front.

For the later history of the 103rd Field Artillery in World War II and the War on Terror, these sources should be consulted:

Harold R. Barker, History of the 43rd Division Artillery, World War II, 1941-1945. Providence: John F. Greene, 1960.