After a slow beginning in the 17th century, the colony of Rhode Island came to dominate the slave trade in British North America in the 18th century.

Slavery by the British began in North America when they brought the first African enslaved captives to the colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619.

Slavery in Rhode Island may have begun with the colony’s establishment in 1636. The first slaves in the colony were surely Native Americans, not Africans. Prisoners of war from the two major Indian wars in southern New England in the 17th century—the Pequot War (1636-37) and King Philip’s/Metacom’s War (1675-76)—became slaves, many of whom were sold abroad. Many more of them became destitute and bound themselves as indentured servants to colonists, some for decades.

The slavery of Native Americans declined as the century wore on, with Providence and Warwick banning their enslavement in 1676. More and more Rhode Islanders wanted to distance themselves from Native Americans and simply did not want them in their settlements, even as slaves and servants. The Newport Town Council eventually made it illegal to sell firearms to Native Americans; Portsmouth banished them to “live in the woods.” Merchants were disallowed from trading with them, selling them liquor, or repairing their firearms.

Seeing the profit to be made, Rhode Island merchants, with their proximity to and affinity for the sea, became a part of the Atlantic trading system of the 18th century, including slave trading. Merchants in Newport, Bristol, and Providence engaged in commerce with West Africa, the West Indies (Caribbean), and North American port cities, exporting lumber, beef, pork, butter, cheese, onions, cider, candles, and horses; and importing sugar, molasses, cotton, ginger, indigo, linen, woolen clothes, and Spanish iron. This trade had positive ripple effects throughout the local economy and the economies of the trading ports.

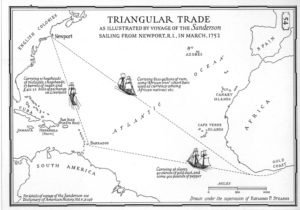

Triangular Trade, as illustrated by a voyage of the Sanderson sailing from Newport, R.I., in March, 1752

African enslaved persons were sparse in the colony of Rhode Island throughout the 17th century, with only 175 in total in 1680. Prior to 1696, the English Royal African Company monopolized the Atlantic slave trade. However, when this was lifted, Rhode Islanders aggressively expanded into the Atlantic trading system, and therefore, the slave trade.

Within 30 years the colony of Rhode Island, and in particular Newport, came to dominate the North American slave trade. Even though it was the smallest of the colonies, the great majority of slave ships leaving British North America came from Rhode Island ports. Historian Christy Clark-Pujara, in her book Dark Work, The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, indicates that during “the colonial period in total, Rhode Island sent 514 slave ships to the coast of West Africa, while the rest of the colonists sent just 189.” Historian Jay Coughtry in The Notorious Triangle, argues that “the Rhode Island slave trade and the American slave trade were virtually synonymous” and that “only in Rhode Island was there anything that can properly be termed a slave trade.”

In 1713, Rhode Island slave traders introduced a new export into the trading system—rum. Slave traders in Africa came to prefer this rum over the previous liquor of choice, French brandy. Within 50 years there were close to 30 distilleries in the colony, 18 in Newport alone. Thus, the so-called “triangular trade” system emerged within the larger Atlantic system. In its simplest form, the system entailed the rum produced in Rhode Island being exported to the slave coast of West Africa. There it was traded for African captives who made the dreaded Middle Passage across the Atlantic, most going to the Caribbean. There they were traded for sugar and molasses, a key ingredient of rum. The molasses was then brought to Rhode Island for processing into more rum.

By 1730, most of the trades and occupations in Rhode Island were somehow related to slavery. Slave traders kept busy shipbuilders, sailors, caulkers, sailmakers, carpenters, rope-makers, painters, barrel-makers, and dock workers. Clerks and warehouse managers administered the system. In addition to these tradesmen, additional crew members were needed to control the enslaved during the voyages.

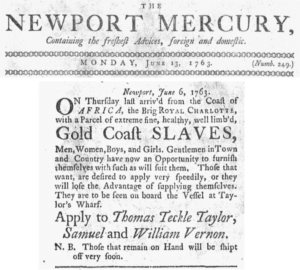

Captives carried involuntarily from the Gold Coast of West Africa advertised for sale by Thomas Taylor, and Samuel and William Vernon, of Newport, in the June 6, 1763 edition of the Newport Mercury. The enslaved persons were available to be viewed at Taylor’s Wharf in Newport on board the slave ship Royal Charlotte, which was to depart for another destination to embark its remaining captives.

In his 1740 report to the British Board of Trade, Rhode Island colonial governor Samuel Ward described the many goods Rhode Island ships provided to “neighboring governments” and also the West Indies—rum, sugar, molasses, lumber, beef, pork, flour, horses, “and our African trade often furnishes them with slaves for their plantations.”

Rhode Island’s dominant role in the Atlantic slave trade explains why the colony came to have the highest percentage of enslaved persons in New England: an estimated 543 in 1720 (5%), 3,347 in 1750 (10%), and 3,761 in 1770 (6%).

Slavery in the Narragansett Country

Most enslaved people imported into the colony of Rhode Island were bought by owners of farms in what we call today “South County” (technically, Washington County) and what in the 18th century was called “the Narragansett Country” (technically, King’s County). Eventually these farms grew to be plantations comparable to small plantations in America’s southern colonies, and with these plantations a class of “Narragansett planters” emerged. By mid-century large plantations thrived from the village of Wickford south to Point Judith and west to Connecticut.

At the heart of the economy of Narragansett Country were products grown and produced by enslaved people. This plantation system bred horses (the famous Narragansett Pacers), cattle, and sheep; produced dairy products, particularly cheese; and also grew Indian corn, rye, hemp, flax, and tobacco. The planters then, through merchants in Newport and Providence, exported these products to southern colonial ports and the West Indies (the Caribbean). Caribbean planters grew mostly sugar cane and the American South planters grew mostly tobacco; they generally did not want to lower their profits by growing crops to feed their enslaved persons. Thus, the New England “carrying trade” was developed to meet the demands for livestock, horses, beef, and dairy products. The wealthiest of the Narragansett planters, such as Robert Hazard, hired ships themselves to export their goods directly.

By the mid-18th century, 20 to 30 families had established farms in Narragansett Country and had acquired slaves—generally from 5 to 40—to work them. By 1740, this area had the highest concentration of enslaved people in the colony; by 1755, one in three residents was an enslaved person. Though only a few Narragansett planters were large slave owners, historian Christy Clark-Pujara states that ultimately “thousands of enslaved men, women, and children” in this area produced foodstuffs and raised livestock for trade.

The planter class made fortunes on the lucrative trade rooted in slavery, especially cheese exports. Competing with dairy farms in the colonies of New Jersey and New York, Rhode Island farmers produced the most cheese of all. Robert Hazard, a successful Narragansett planter, owned seventeen acres, had about one hundred cows, and produced 13,000 pounds of cheese annually. The Champlin farm had 42 cows that produced 9,200 pounds annually.

The wealth of the planter class enabled the families to lead an elaborate lifestyle, similar to southern planters. They commissioned portraits, hired private tutors for their children, took European vacations, enjoyed horse-racing, and sought to imitate the lifestyle of the landed gentry of England. They also dominated the political affairs of the region.

Richard Smith, Jr., was one of the first Narragansett planters. He inherited his farm from his father, Richard Smith, a contemporary of Roger Williams, the founder of the colony and of Providence. The site of the farm was an area called “Cocumscussoc” by the Narragansett Native Americans. Williams had established a trading post there with the Native Americans and learned their language and customs. Williams reportedly said that Smith: “Put up …the first English house…in Nahigonsik Countrey.”

Smith, Jr., died in 1692, leaving the farm to the Updikes who developed it into one the great plantations of 18th century New England. At its height, it contained more than 3,000 acres, and was divided into five farms, worked by tenant farmers, indentured servants, and enslaved people. The Updikes dealt primarily in livestock and dairy products, producing cheese, other farm crops, and a breed of horse known as the Narragansett pacer.

Cocumscussoc still exists today as a park along with a colonial house known as Smith’s Castle, seasonally open to the public. (See www.smithscastle.org).

This plantation system flourished until the late 1760s. Planters tended to divide their estates among all their children, thus making the farms smaller and smaller. The final blow came with disruptions caused by the American Revolution and the British-Hessian occupation of Newport from 1776 to 1779.

The Business of Slavery in Colonial Newport

The histories of colonial Newport and of slavery in the New World are intimately connected. The first record of Rhode Islanders buying enslaved person directly from Africa was on May 30, 1696, when 14 captive Africans were bought from the ship Seaflower in Newport “for betwixt 30£ and 35£” (British pounds).

“Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam,” by John Greenwood, between 1752 and 1758. The painting shows several Rhode Island sea captains enjoying themselves at a tavern in the Dutch-controlled Caribbean island of Surinam.

From this beginning, Rhode Island slave traders by 1730 came to dominate the American trade in slaves, and Newport became the most important slave-trading port of departure in North America, according to historian Christy Clark-Pujara, in her book, Dark Work.

Newport today is dotted with the names of many of the merchants who took part in this commerce: Malbone, Banister, Gardner, Wanton, Brenton, Collins, Vernon, Channing, Champlin, and Lopez.

Between 1761 and 1774, Aaron Lopez and father-in-law Jacob Rodriguez Rivera, among the many ships they launched, sent 14 slave ships to the west coast of Africa. Their first voyage contained flour from Philadelphia, beef from New York, and 15,281 gallons of rum from Newport distilleries. Over the 14 year period it is estimated that their ships brought over 1,100 slaves from West Africa to the West Indies and the southern colonies of America. The trade with the West Indies was key because this is where the molasses was acquired for the Newport rum distilleries. Lopez personally owned five enslaved persons and Rivera owned twelve.

The sloop Adventure, owned by Christopher and George Champlin, sailed from Newport in 1773, outfitted with slave shackles, vinegar, pork, beef, sugar, molasses, wine, beans, tobacco, butter, bread, flour, and 24,380 gallons of rum for the purchase of slaves. Enslaved women cost at the time an average of 190 gallons of rum, while men averaged 220 gallons.

In his book, African Americans in Newport, Richard Youngken reports that Newporters prior to the Revolution took a total of 59,067 individuals from the West Coast of Africa, a small number compared to the total 10-15 million slaves taken to the New World. He estimates that only about 2% were actually brought to Newport and sold to Newporters. The rest were sold in the West Indies and southern American ports.

Anthropologist Akeia Benard, in her forthcoming book, Strangers and Outcasts in a Strange Land: The Early African American Community of Newport, RI, summarizes data from several sources on the black population in 18th century Newport. In 1730, the African American population represented 14% of the population (1,649 individuals) and in 1748, African Americans represented 17% of the population (1,105 individuals). The African American population peaked in 1755, representing 18% of Newport’s population (1,234 individuals). The population dropped to 14% of the population (1,246 individuals) by the time of the first census (1774) that gave figures for both enslaved and free African Americans. Of the 1,246 African Americans in the census that year, 145 individuals, approximately 9%, were listed as “Free”.

Youngken indicates that during the middle decades of the 18th century about 30% of white families in the city owned enslaved persons. Clearly slave sales must have been normal in Newport, and enslaved people must have been common throughout the city.

In Newport, enslaved women worked primarily as domestic servants while the enslaved men worked in candle-making, rum distillery, husbandry, metal-smithing, sailing, whaling, and manual labor. It is tragic irony that many of the enslaved worked in the very business of slavery.

Merchants from Newport paid significant taxes and duties to the city, which allowed public works projects. Clark-Pujara concludes: “The streets of Newport were paved and its bridges and country roads mended through the duties collected on slave imports. In many ways, the business of slavery literally built Rhode Island.”

“This stone was cut by Pompe Stevens in memory of his brother Cuff Gibbs.” Common Burying Ground in Newport (Fred Zilian)

Two projects now exist to raise our level of awareness of slave history in Rhode Island, making it more complex and comprehensive. The Newport Middle Passage Port Marker Project, led by Victoria Johnson, seeks to remember, honor and commemorate the contributions of those Africans who perished in the Middle Passage journey and to acknowledge those survivors who helped build Newport and the nation economically and culturally. (See (www.Newportmiddlepassageproject.org).

The Rhode Island Slave History Medallions project, led by Charles Roberts, has as its mission increasing public awareness of the state’s slave history by marking pertinent locations with medallions linked to a dynamic, informative website at www.rishm.org.

[Banner image: “Here lieth Edward, Negro Servant to Henry Collins, died Febry 16th 1738/9 in ye 21st year of his age. He was faithful and well beloved of his Master.” Common Burying Ground, Newport [Christian McBurney]]

Sources:

Benard, Akeia. Strangers and Outcasts in a Strange Land: The Early African American Community of Newport, RI. (forthcoming)

Clark-Pujara, Christy. Dark Work, The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. NY: New York University Press, 2016.

Coughtry, Jay. The Notorious Triangle, Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981.

Crane, Elaine F. A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island, in the Revolutionary Era. NY: Fordham University Press, 1992.

Johnson, Cynthia M. James DeWolf and the Rhode Island Slave Trade. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014.

Kelley, Robin D.G. and Earl Lewis. To Make Our World Anew, A History of African Americans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

McBurney, Christian. The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, vol. 45, no. 3 (August 1986), 81-93.

O’Toole, Marjory Gomez. If Jane Should Want to Be Sold, Stories of Enslavement, Indenture and Freedom in Little Compton, Rhode Island. Little Compton Historical Society/Sheridan Books, 2016.

Stensrud, Rockwell. Newport, A Lively Experiment, 1939-1969. London: D Giles Limited, 2015.

Woodward, Carl R. Plantation in Yankeeland: The Story of Cocumscussoc, Mirror of Colonial Rhode Island. RI: Narragansett Publishing, 1985.

Youngken, Richard C. African Americans in Newport, An Introduction to the Heritage of African Americans in Newport, Rhode Island, 1700-1945. Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, 1998.