In its current form, the Masonic fraternity dates back to the founding of the Grand Lodge of England in 1717. The new fraternity used stonemasonry and the biblical account of the building of King Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem as the basis for its mythology and as the means to teach initiates moral lessons, while emphasizing the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, and requiring that its members believe in a Supreme Being. Despite a facade of religious universality, the fraternity was often avowedly Christian in practice, but this did not prevent Jews in Europe and the American colonies who were eager for interaction with their Christian neighbors from seeking to join. Historian Samuel Oppenheim writes of eighteenth-century Jewish Masonic involvement: “The relationship of the Jews to the Order brought them naturally more directly in contact with their Christian brethren than would otherwise have probably been the case, and the respect and esteem with which the individual members of the race were regarded no doubt tended to the advantage of their coreligionists as a body.”[1]

Beginning in 1813, the fraternity in England underwent a conscious process of de-Christianization, making it more amenable to Jewish membership. Lodges in the United States did not follow suit, however, and a de-Christianization process akin to the one that occurred in England never took place in Rhode Island. Still, Jews in the United States continued to be drawn to the fraternity and its pledge of equality for all men. Historian Tony Fels notes that “the principle of Masonic universalism, which promised that the distinctions based on blood and birth would be washed away in the solvent of brotherhood, shone as a beacon from the Protestant world pointing toward fulfillment of these Jewish hopes. Nearly every Jewish Mason whose writings have survived from the nineteenth century—both in Europe and the United States—emphasized this aspect of Freemasonry above all others.”[2]

In 1877, the formerly-Orthodox Congregation of the Sons of Israel and David (better known today as Providence’s Temple Beth-El) became Rhode Island’s first Reform congregation. That year, ten of its members also resolved to form a new Masonic lodge in Rhode Island: Redwood Lodge No. 35. Their endeavor was consistent with nineteenth-century Reform Jews’ preoccupation with integrating into the Christian social fabric of Europe and the United States. Redwood’s formation served both to bring together Rhode Island’s Jewish Freemasons and to link the state’s new Reform congregation with an established, respected, and mostly Protestant fraternity.

The endeavor also entailed several peculiar and enduring accommodations on the part of Rhode Island’s Jewish Freemasons: Redwood has a phrase about Jesus for its motto; is dedicated to two Christian saints; and adheres to a Masonic ritual emphasizing the need for faith in Jesus and asserting Judaism’s inferiority to Christianity. The story of Redwood’s founding and development illustrates the way American Jews have negotiated membership in a sometimes avowedly Christian Masonic fraternity and about the reasons why they have chosen to do so.

A driving force behind the Reform restructuring of the then-Orthodox Congregation of the Sons of Israel and David, and behind Redwood’s founding, was Myer Noot, who subsequently served the congregation in such varied capacities as secretary, vice-president, teacher, dues-collector, cantor, and (though not ordained) rabbi. Henry Green, who served as the Sons of Israel and David’s president for some twenty years, became Redwood’s first Senior Warden, and Leopold Hartman became its first Junior Warden. Green and Hartman had likewise been instrumental in the Reform restructuring of the Sons of Israel and David.

These men and Redwood’s other founders originally considered calling their unique Masonic lodge “Liberty.” Earl H. Mason’s 1953 “Historical Sketch and other Pertinent Data of Redwood Lodge” explains that in deciding to name the lodge after Abraham Redwood (1709-1788), “the organizers chose to honor a non-Mason from Newport, famed for his philanthropy, broadmindedness and general good citizenship . . . a staunch Quaker, who numbered many Masonic and Jewish leaders of his day among his closest and most loyal friends.”[3] This naming of a mostly-Jewish Masonic lodge after a tolerant Newport Quaker who “befriended many of the Jewish people in that city” points to the cosmopolitanism that Redwood’s founders were striving for.

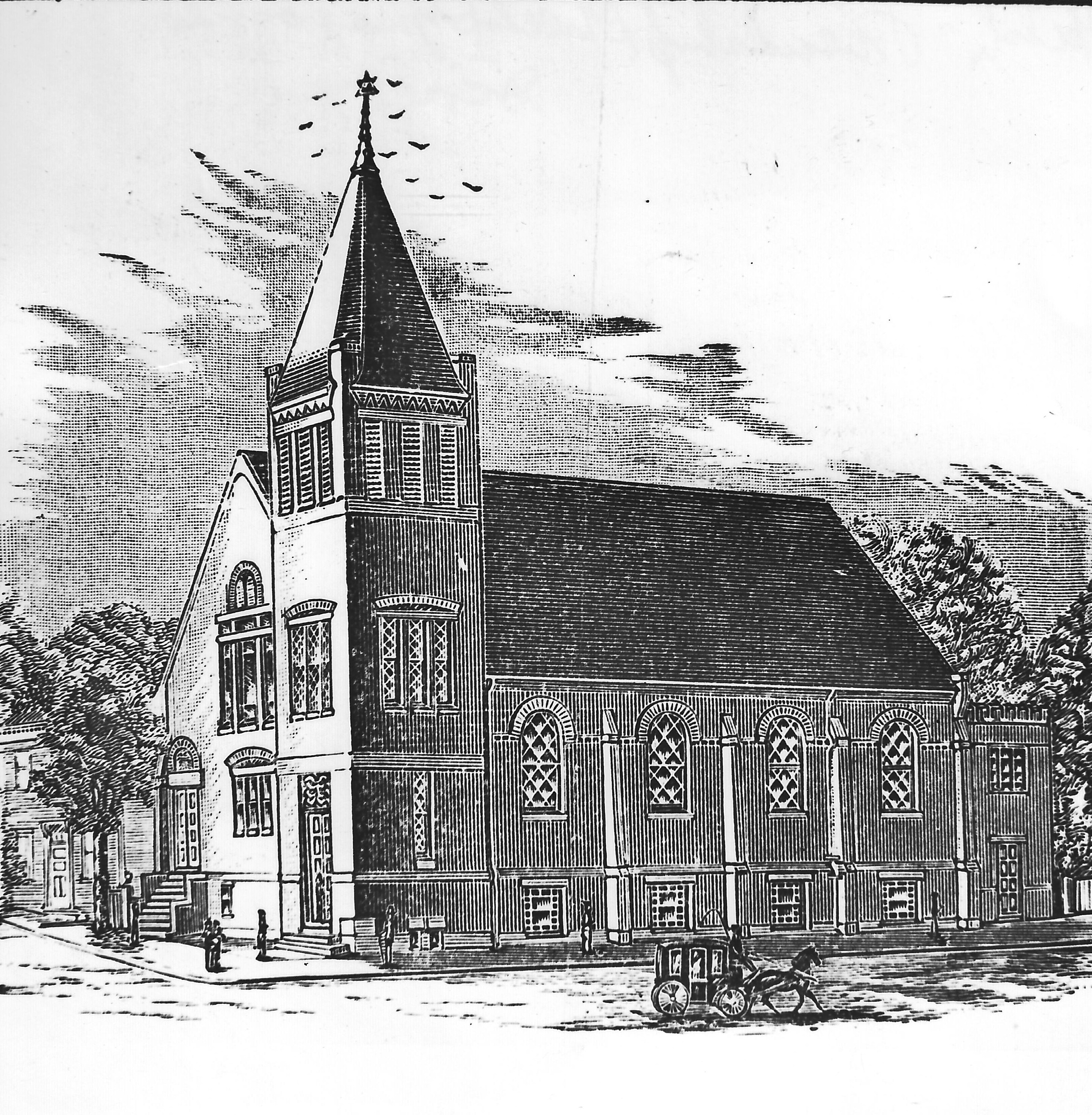

The extent to which Redwood’s Reform founders succeeded in integrating their congregation into the Christian social fabric of Rhode Island, and in gaining the recognition and respect of their non-Jewish neighbors — as well as the extent to which Freemasonry played a part in that process — was fully evident when the Sons of Israel and David purchased land and moved forward with plans to construct Providence’s first synagogue. As reported in The Providence Journal, in September 1889, “with the substantial co-operation of friends of other [that is, Christian] religious denominations,” an elaborate cornerstone ceremony was conducted for the congregation by the Grand Lodge of Rhode Island. A Masonic procession set out from Freemasons Hall, the Grand Lodge building, and made its way to the Sons of Israel and David’s recently purchased land. Redwood acted as an escort to the Grand Lodge on this occasion and its by-laws were among the Masonic documents placed in a box beneath the synagogue’s cornerstone.[4]

Dedicated in 1890, the Sons of Israel and David’s synagogue building was the first constructed in Providence. It was used by the congregation until 1911 (Sketch, “Friendship Street Synagogue,” Courtesy of the Rhode Island Jewish Historical Association).

In his 1982 Centennial History of Redwood Lodge, Louis B. Rubinstein records that the “relationship between the Congregation Sons of Israel and David and Redwood Lodge continued [after the cornerstone ceremony] and persists to the present, with many of Redwood’s membership also active in that congregation.”[5] Moreover, Redwood went on to attract not only Rhode Island’s Reform Jews, but Conservative and Orthodox ones as well.

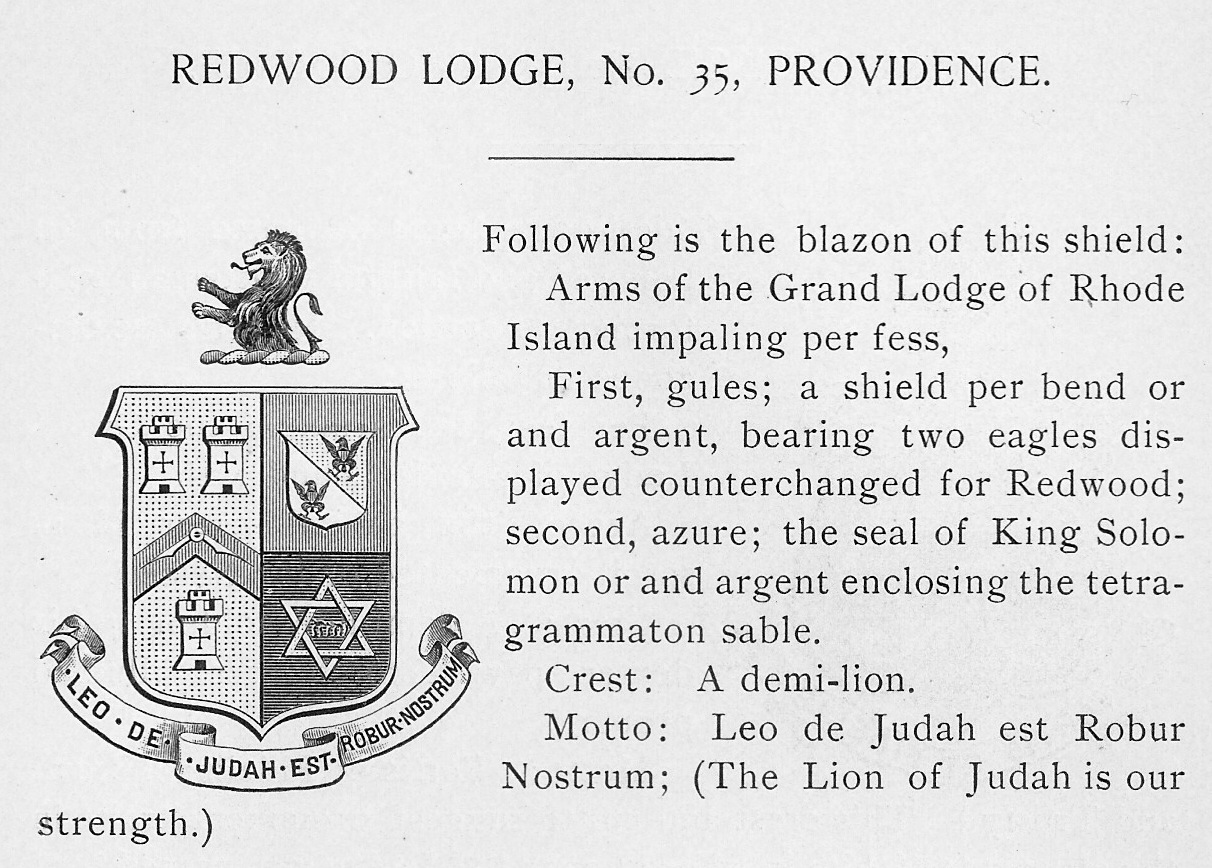

This Jewish integration into Rhode Island’s decidedly Christian-oriented branch of the global Masonic fraternity by means of Redwood Lodge resulted in some unusual circumstances. Redwood’s coat of arms demonstrates the disjuncture between Jewish identity and a Rhode Island Masonic tradition infused with Christian doctrine. Redwood’s crest is the profile of a prominent demi-lion. On its shield are two eagles; a six pointed star (the Seal of Solomon/Star of David) enclosing the Tetragrammaton; and a compass and three turrets. Beneath the shield is the lodge’s motto: “Leo de Judah est Robur Nostrum,” a Latin phrase meaning “the Lion of Judah is our strength.” The Biblical Index to Freemasonry provided in the Heirloom Masonic Bible gives the following catechistic explanation of the phrase “Lion of the tribe of Judah.”

Q: What is the symbolism of this phrase?

A: . . . The Masonic use of the phrase “Lion of the tribe of Judah” is Messianic in its significance; it refers to Christ, who “brought life and immortality to life.”[6]

In other words, “the Lion of Judah” or “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” referred to in Redwood Lodge’s motto is Jesus. In selecting the Latin motto “Leo de Judah est Robur Nostrum,” Redwood’s Reform founders embraced a phrase that means “Jesus Christ is our strength.”

American Craft or Symbolic lodges have three separate initiation ceremonies, or degrees, in which Freemasonry’s symbols and philosophy are imparted to initiates. This is done through lectures, catechistic question and answer, and dramatic reenactments of Masonic lore. These three degrees are the first/Entered Apprentice degree, the second/fellowcraft Degree, and the third/master Mason degree.

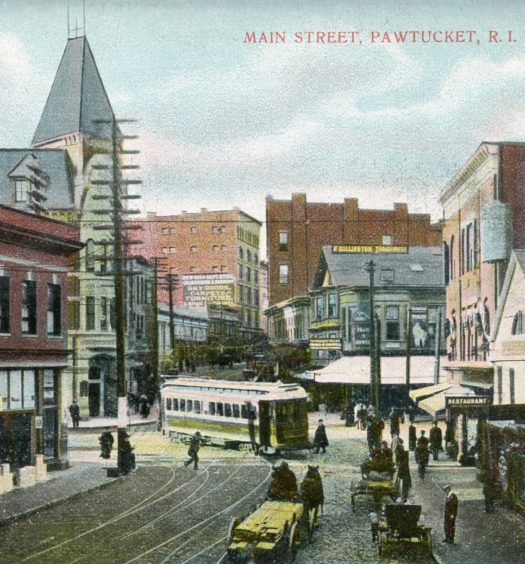

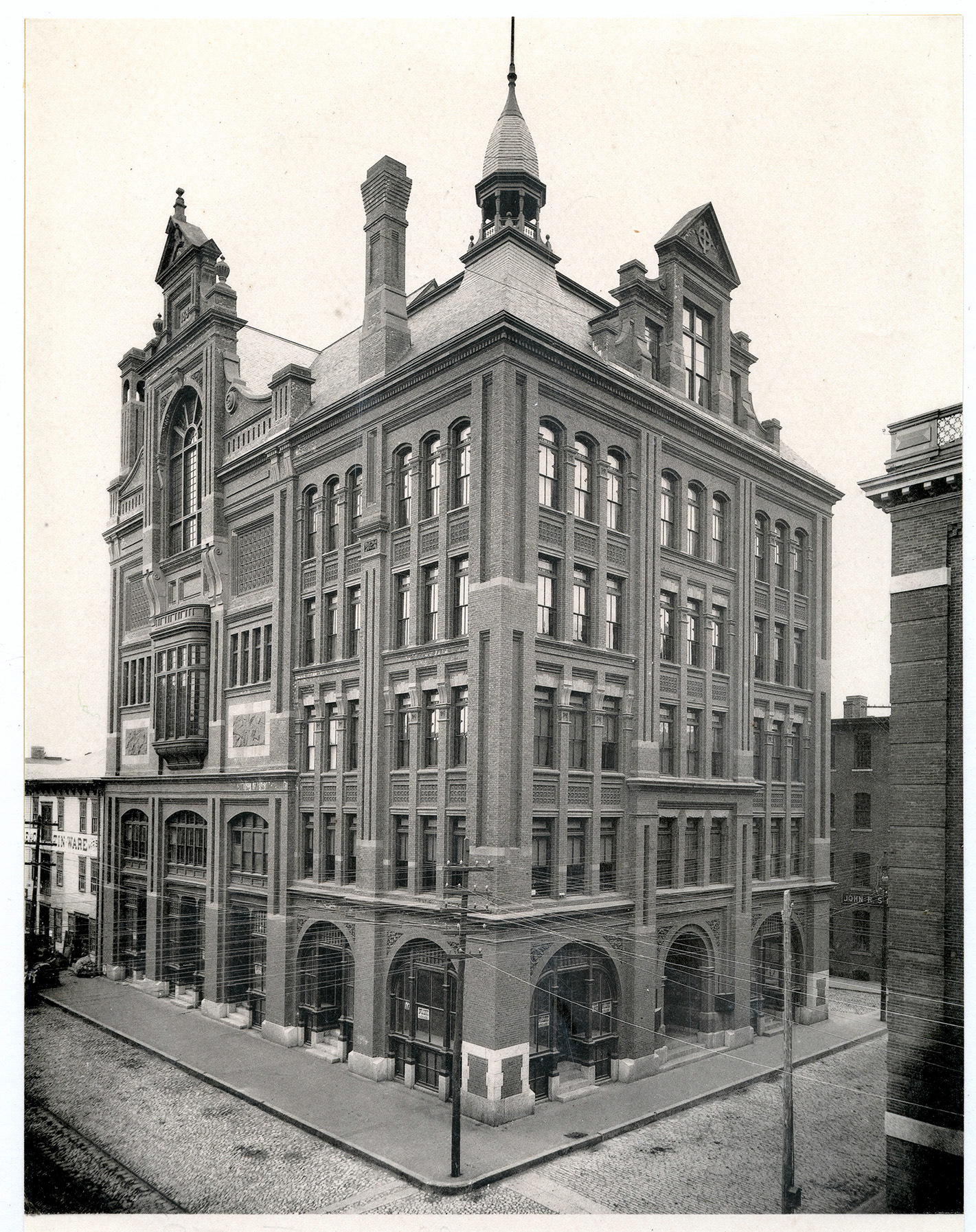

In September 1889, a Masonic procession set out from Freemasons Hall and made its way to the land recently purchased by the Sons of Israel and David. Redwood Lodge’s members escorted the Grand Lodge officers, and Redwood’s by-laws were among the Masonic documents placed beneath the synagogue’s cornerstone. Freemasons Hall was destroyed by fire in 1896. [Freemason’s Hall, VM013_WC0272, Rhode Island Photograph Collection, Providence Public Library)

Thus, my brother, we close the explanation of the emblems, upon the solemn thought of death; which, without revelation, is dark and gloomy; but the Christian is suddenly revived by an ever-green, ever-living sprig of Faith in the merits of the Lion of the tribe of Judah, which inspires him to look forward with calmness and composure to a blessed immortality; so that he doubts not, that on the glorious morn of the Resurrection, the body will be raised and become as incorruptible as the soul.[7]

Other passages about bodily resurrection in Rhode Island’s third degree argue the superiority of “the Christian dispensation” (Christianity) over “the Jewish hierarchy” (Judaism), and of both over the “state of nature” that preceded them.[8] These statements link the Master Mason degree with the Christian religion while proclaiming Christianity to be the most complete religious stage humanity has passed through. Christianity is declared superior to Judaism because the former purportedly attests to the doctrine of future bodily resurrection from the grave. A search through the scriptures of “the Jewish hierarchy” (that is, the Hebrew Bible), by contrast, is said not to yield a single passage convincingly proving resurrection, and this supposed lacuna is claimed as evidence of Judaism’s inferiority. In this manner Rhode Island’s third degree reiterates supercessionist/replacement theology — the religious doctrine that Christianity has superseded and replaced Judaism — within a Masonic framework.

Were they at all attentive to the content of Masonic rituals, lectures, and orations in Rhode Island, Redwood’s Reform founders and early Jewish members could not have avoided perceiving at least some of their Christian aspects. Evidently, the men who formed Redwood were not overly concerned about such Christian manifestations, including within their own lodge. For a time, during 1889 and 1890, it was even unclear to many observers whether or not Providence’s early Reform Jews were as unconcerned about Christian Masonic rituals being carried out in connection with their synagogue.

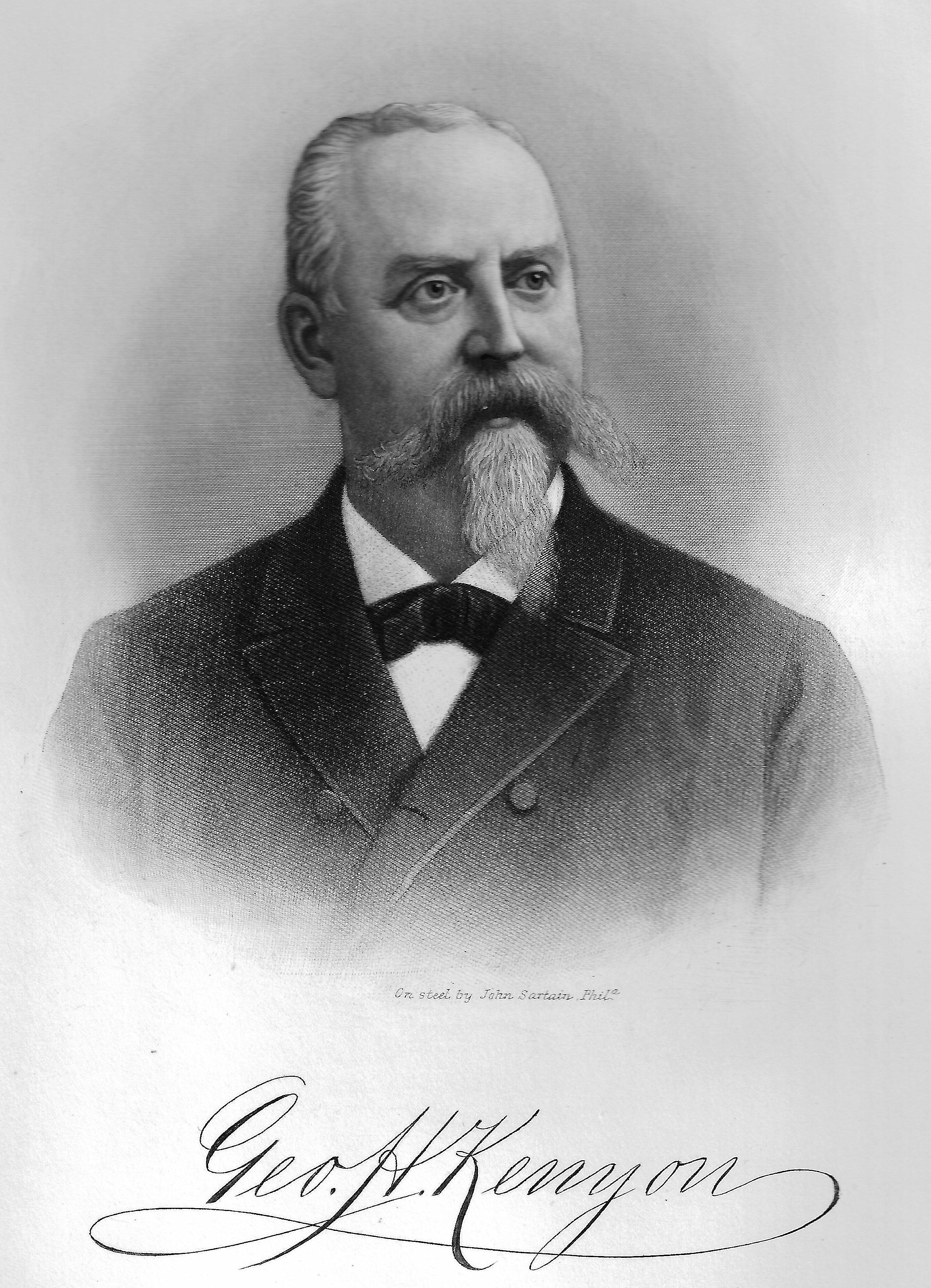

According to The Providence Journal, the September 1889 Masonic cornerstone ceremony that the Grand Lodge conducted for the Sons of Israel and David included Christian prayer (the Lord’s Prayer) and invoked the patronage of Christian saints. As reported in that newspaper, after a brief address about the congregation’s history, its president, Alexander Strauss, requested that Grand Master George H. Kenyon lay the cornerstone: “Most Worshipful Grand Master of Masons of the State of Rhode Island: The Congregation Sons of Israel are about to have this structure erected for the purpose of worshipping God the Almighty, and perpetuating our faith, and in their behalf I most respectfully request you to lay the corner-stone, according to the ancient rites and usages of Free Masons.”

The Providence Journal described the following as occurring: Grand Chaplain Alfred Manchester “began the office,” commencing a call and response of Biblical verses. He then said, “Let us pray,” after which “the Grand Chaplain and the people united in the Lord’s prayer.” The Grand Chaplain’s Christian prayer was followed by an oration by Rabbi Morris Sessler and by other exercises. Prior to consecrating the cornerstone, “[t]he Grand Master approached the stone, and, striking it three times with his gavel, said: ‘To the glory of God, under the patronage of the Holy Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist, I declare this stone to be well formed, true and trusty, and laid by us in ample form.’” The cornerstone “exercises were concluded with the benediction by the Rabbi, with response by the choir.”[9]

Reports of the Christianity-infused Masonic cornerstone ceremony soon circulated, eliciting widespread opprobrium. Some of the commentary in Masonic publications touched on the pronounced difference between English and American lodges when it came to accommodating Jewish members. In February 1890, the editor of The Freemason’s Chronicle (a weekly published in London), declared in a front-page article entitled “Judaism and Freemasonry” that American Freemasons would do well to emulate English de-Christianization:

An instance has recently occurred . . . proving that it is absolutely necessary to sometimes adopt our ritual to circumstances, rather than to maintain a rigid observance of the actual letter of our ceremonies. It appears the corner stone of a new Synagogue was to be laid at an American town, and the Masonic Order was honoured in being asked to perform the ceremony with Masonic rites, the Grand Master of the District himself undertaking to conduct the work. All went well, observes one of the Jewish journals, “until the presiding official came out with the following declaration:—‘To the glory of God, and under the patronage of the holy saints—Saints John the Baptist and the Evangelist—I declare the stone to be well formed, &c.’’’

. . . Of course it will never be possible to wholly disassociate the names of the two Saints John from Freemasonry, but it is possible to reduce reference to them to a minimum—also to a vanishing point—such as is the system adopted in England, a system that might well be followed in some parts of America and other quarters of the globe.[10]

Another comment on the corner stone ceremony, titled “Contemptuous treatment of Jews by American Masons,” was published in The Freemason’s Chronicle in mid-March. In this letter to the editor, the Bostonian Jacob Norton (who had formerly lived in London and been made a Freemason there) contrasted what he considered to be the gentlemanly conduct toward Jews in English lodges with the insulting conditions he found in American ones:

Outside of a Masonic gathering the American Jew, when associating with any kind of decently behaving Christian society [in America], is treated as gentlemanly as the Jew is treated in similar good society in England. But in a Masonic Lodge the Jew receives a very different kind of treatment in America to what he receives in an English Lodge. In my younger days I imagined that a Masonic Grand Lodge was a focus of wisdom and justice. I have, however, long since found out my mistake. I am now a firm believer that in America at least a Grand Lodge is a compound of credulity and Jesuitism. Hence, under the pretence of “ancient landmarks,” they assume a right to insult a Jew in a Masonic Lodge, which they would not dare to do when not decorated with a Masonic apron, Square, Compasses, &c. Here [that is, the cornerstone ceremony for the new synagogue in Providence] is an instance or case in point.[11]

Norton, who wished to know what Providence’s Jews thought and said of the Grand Lodge ceremony, promised to look into the matter and update the Freemason’s Chronicle about his findings. In the meantime, Henry W. Rugg, who was editor of The Freemasons Repository, a Masonic monthly published in Providence, responded to the February Freemason’s Chronicle editorial with his own “Judaism and Freemasonry.” Though identically titled, Rugg’s editorial was palpably different in tone and approach from what had been published in England about the cornerstone ceremony. Employing the editorial we, he avowed in the American monthly that Christian language had indeed been used in the cornerstone ceremony, but that this was of no consequence, as the proper response for Jews was to not be insulted by such seeming tactlessness:

Our Jewish Brethren, belonging to a people ever faithful to the religion of their ancestors, must not be quick to take offence where none is intended. They must expect, as we know some of the most intelligent of the Hebrew Masons do expect, that in a Fraternity where the Christian element constitutes so considerable a majority there will be some expressions occasionally in form, ritual, prayers, or special services, to which under other circumstances they would take objection. For their own peace of mind they will do well not to be over sensitive or over critical regarding allusions to the distinctive Christian features supposed by some to attach to Freemasonry.

Grand Master George H. Kenyon (G.M. 1889-1891) laid the cornerstone of the Sons of Israel and David’s synagogue in 1889, and maintained that the Masonic cornerstone ceremony had been slightly modified in order to “make it conform to the Jewish faith” (Rugg, History of Freemasonry in Rhode Island, 1895, frontispiece)

. . . we allude to this matter to make the statement that the Jewish Brethren gathered at that corner stone laying were not greatly troubled at the form of words used in the ritual, and the special allusion to the Saints. As one prominent Jew remarked in our hearing: “We knew that no offence was intended, and therefore did not feel insulted, scarcely annoyed, by the form used in placing the foundation stone of our new Synagogue.” This, we think, is the proper view to be taken by members of the Hebrew faith in all cases where Masonic teaching and services may not quite harmonize with their own ideas.[12]

About a month after he had first stated his intention to update the Freemason’s Chronicle on the cornerstone ceremony, Norton shared his findings in the article “Not so bad as at first supposed.” Based on information provided to him by a Jewish non-Mason who had been present at the cornerstone ceremony, Norton concluded that Christian terminology had not actually been used there:

. . . Bro. Rugg’s testimony certainly confirms the report that was circulated in the Jewish papers, that the corner stone was laid in accordance with the printed ritual. But, on the other hand, my informant assured me that Bro. Rugg was not present at the laying of the said corner-stone.

. . . until otherwise proved, I shall indulge in the hope that good manners are not altogether extinct, even in the very pious Masonic Grand Lodge of Rhode Island.[13]

Norton’s indulgence proved wise. In March 1890, Rugg — again employing the editorial we — informed readers of The Freemasons Repository that Christian language had not been used as part of the cornerstone ceremony:

We supposed the allegation in regard to a reference to the Saints John in a Masonic ritual used at the laying of the corner-stone of a Jewish synagogue, to be in accordance with the facts in the case.

We are assured on the best authority that no such reference was made in the ceremony—that the words alleged to have been uttered were not spoken by the presiding officer or anyone else taking part in the services of that occasion.[14]

The movement of the Sons of Israel and David away from Orthodox and toward Reform Judaism in the 1870’s had been motivated, in part, by its members’ desire to better integrate into American society, while at the same time retaining their Judaism. The parallel formation of a Jewish-majority Masonic lodge was an extension of this goal. In early nineteenth-century England, Masonic Craft lodges underwent an extensive process of de-Christianization, but Jewish Freemasons in Rhode Island, from the eighteenth century to the present, have tacitly accepted a Craft ritual based on doctrine alien to their own religious beliefs, which elevates the intrinsic worth of Christianity over Judaism.

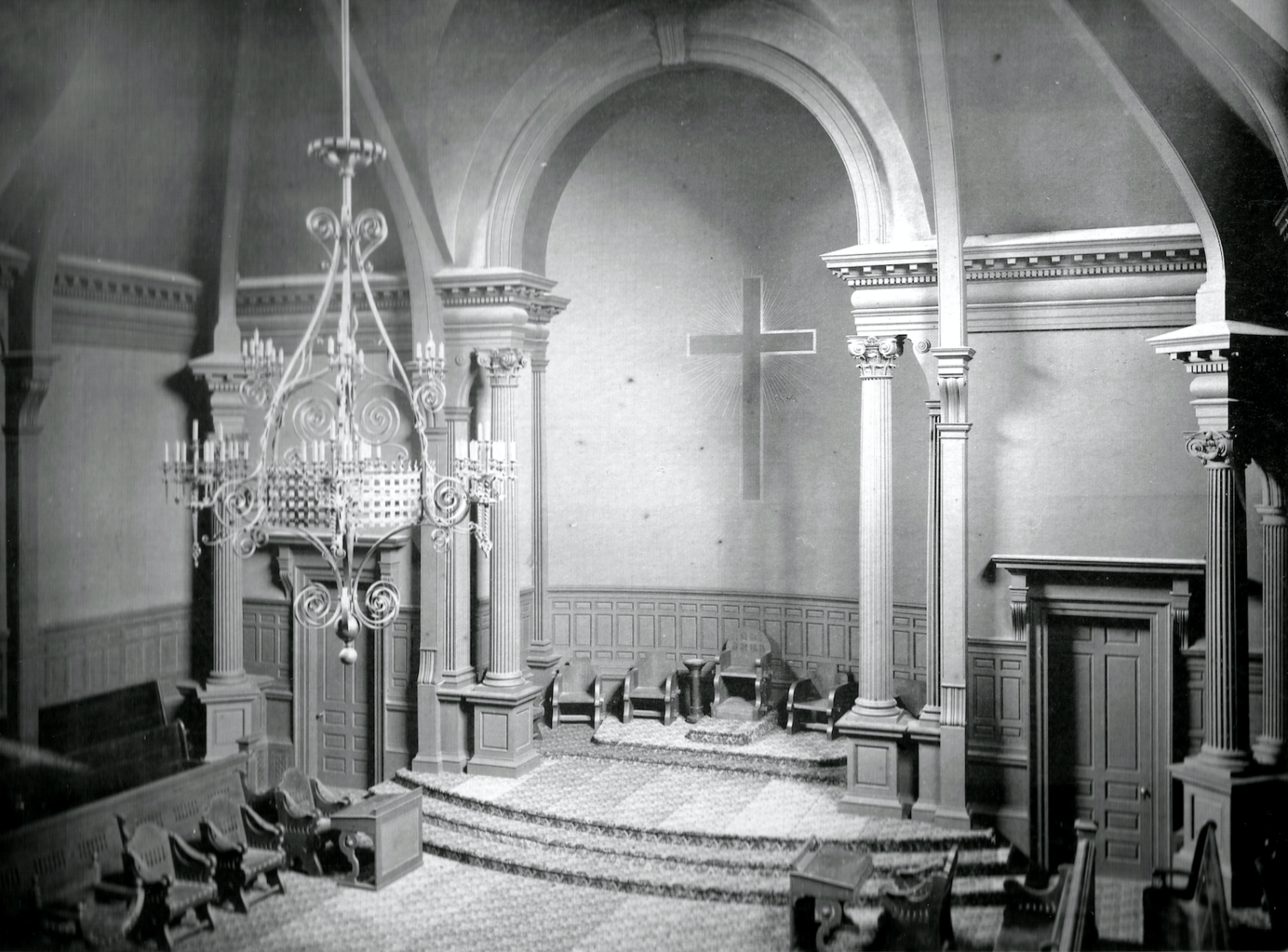

[Banner Image: The interior of the chapel at Freemasons Hall in Providence (Author’s Collection)]

Notes:

- Samuel Oppenheim, “The Jews and Masonry in the United States before 1810,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 19 (1910): 2-3.

- Tony Fels, “Religious Assimilation in a Fraternal Organization: Jews and Freemasonry in Gilded Age San Francisco,” in Freemasonry on Both Sides of the Atlantic, ed. R. William Weisberger (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 636.

- Earl H. Mason, “Historical Sketch and other Pertinent Data of Redwood Lodge Number Thirty-Five A. F. & A. M.,” in Redwood’s Diamond Jubilee (1953) [unpaginated booklet].

- “Jewish Synagogue. Laying of the Corner Stone with Masonic Ceremonial,” The Providence Journal, 24 September, 1889, 6.

- Louis B. Rubinstein, A Centennial History of Redwood Lodge Number 35 A.F. & A.M. in the Grand Jurisdiction of Rhode Island (1982), 9-10.

- Holy Bible (Wichita: Heirloom Bible Publishers, 1988), 49.

- The Trestle-Board for the use of the Subordinate Lodges under the Jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons for the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Providence: Grand Lodge, 1988), 50-51.

- See Revised Cipher for Subordinate Lodges, Jurisdiction of the Most Ancient and Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons for the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (1986), 72.

- “Jewish Synagogue,” The Providence Journal, 24 September, 1889, 6.

- “Judaism and Freemasonry,” Freemason’s Chronicle, 1 February, 1890, 1.

- Jacob Norton, “Contemptuous treatment of Jews by American Masons,” Freemason’s Chronicle, 15 March, 1890 (written 28 February, 1890), 11.

- “Judaism and Freemasonry,” Freemasons Repository 29, 5 (February 1890): 40-41.

- Norton, “Not so bad as at first supposed,” Freemason’s Chronicle, 12 April, 1890 (written 28 March, 1890), 4.

- “Judaism and Freemasonry,” Freemasons Repository 29, 6 (March 1890): 45.