The emigration of French Canadians to the United States, particularly New England, during the period from 1860 to 1924 caused a depletion of the Quebec countryside. By 1900 more than 700,000 French Canadians resided within the borders of the United States, and of this number approximately 500,000 had settled in New England. This large exodus served to enrich American culture and invigorate Catholicism in the northeastern regions of the United States.

Less than a year after the British came to Jamestown, Samuel Champlain chose Quebec in 1608 as the first settlement of New France. The French Jesuits who accompanied this intrepid explorer made Catholicism an integral part of the colony. This tiny settlement was slowly and sporadically nourished by immigrants from the mother country as the French presence in the New World took shape. The French government, in an effort to encourage settlement, offered to its lesser nobility grants of land in Canada called seigneuries. The landlords, or seigneurs, parceled out their holdings to colonists, but their attempt to establish the feudal system in the New World met with only limited success.

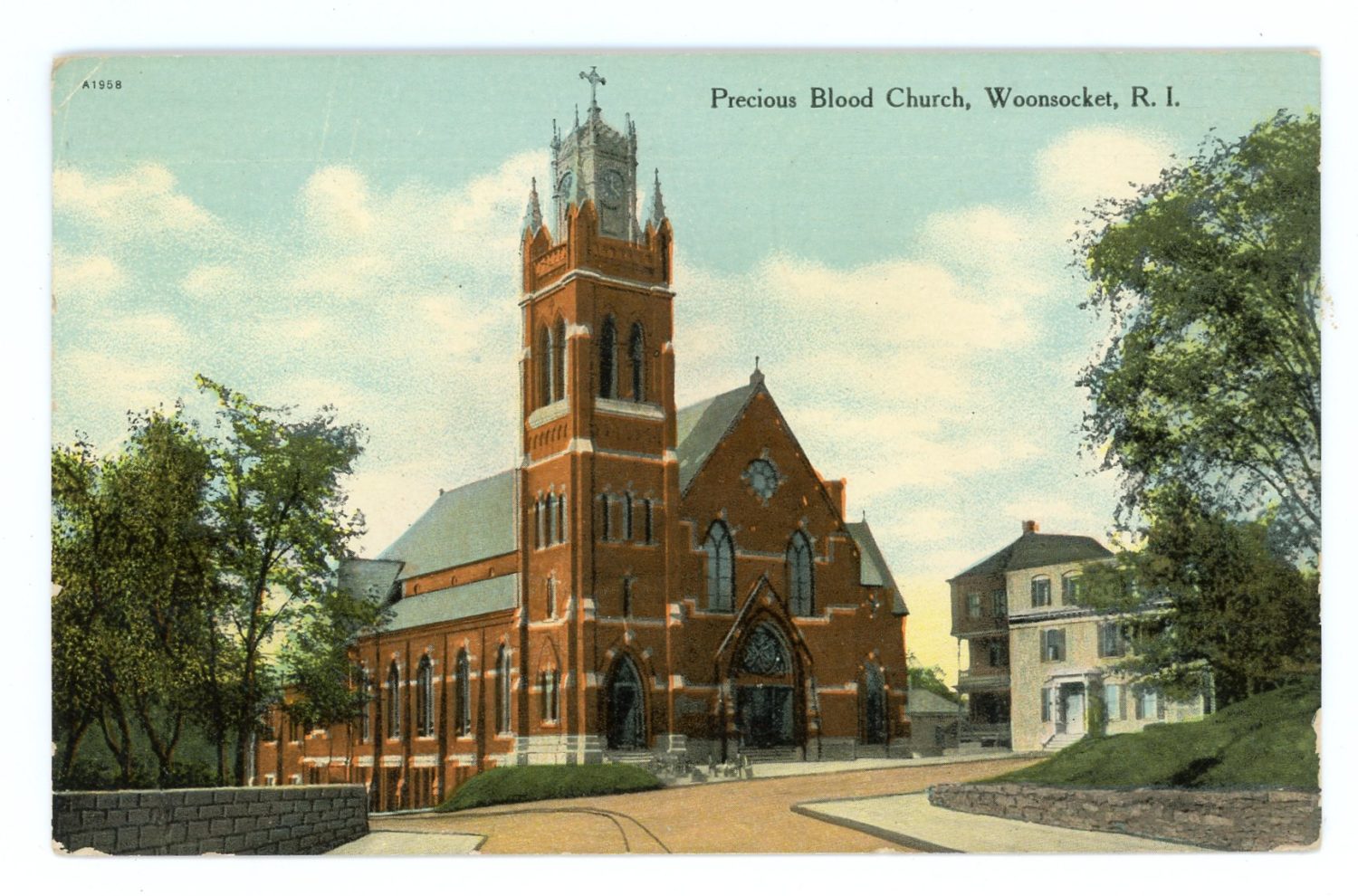

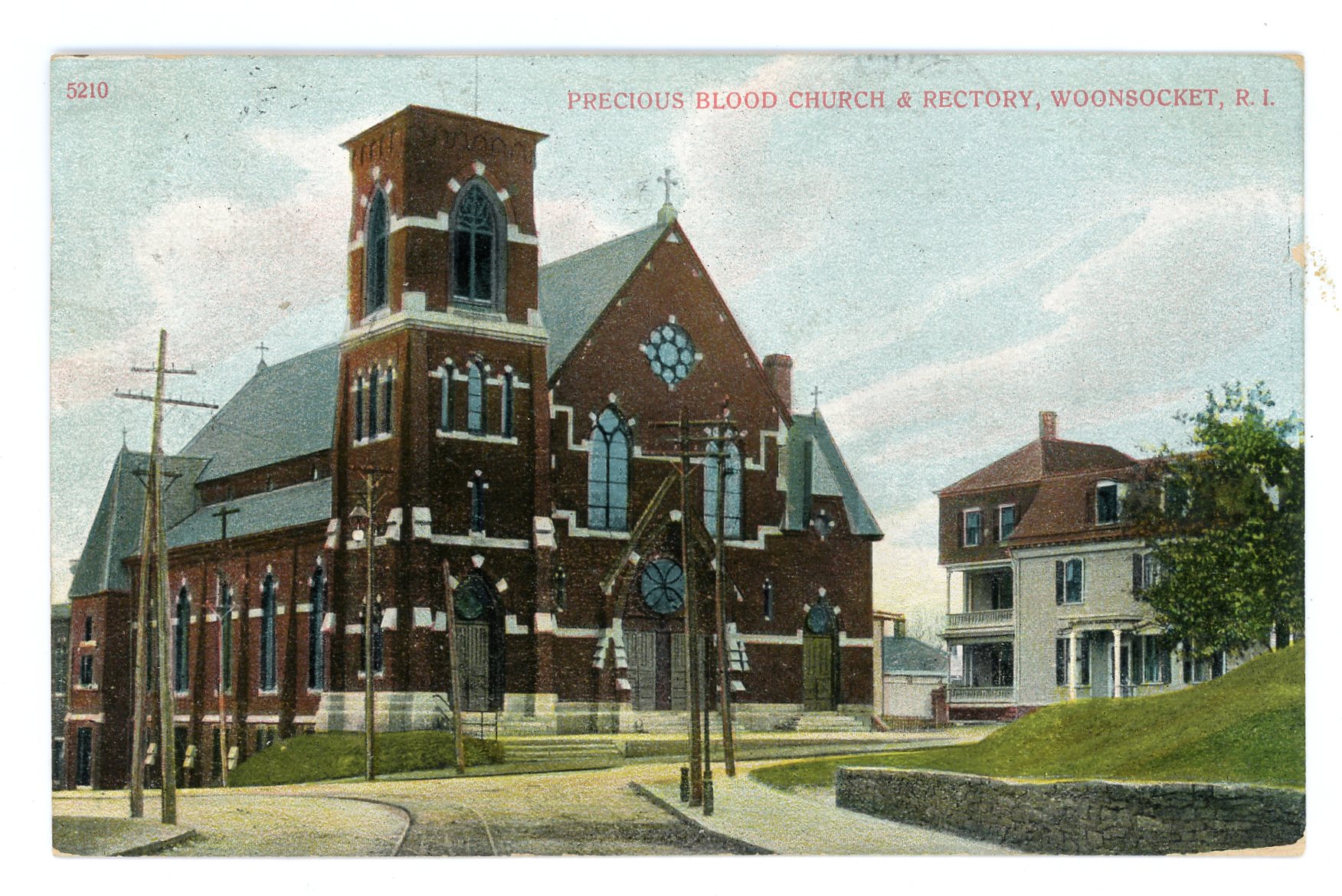

Church of the Precious Blood, in Woonsocket, founded in 1872. Construction started in 1873, and after a storm damaged it, was completed in 1881. The tower was increased in height in 1910. (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Other efforts to stimulate settlement in New France were also unproductive. By 1673 the colonial population of Canada was still less than 10,000. It is perhaps this failure of the mother country to supply her American colony with an adequate number of immigrants that resulted in the Canadian predilection towards early marriages and large families.

There was, however, one notable instance of significant French migration to Canada: the emigration of the Filles du Roi— in English, the King’s Daughters—to Quebec during the decade from 1663 to 1673. This migration consisted of approximately 700 women who left their lives in France behind to marry men in Quebec whom they had never met and to spend the remainder of their lives on the frontier of New France building homes and raising families. Although their impact on population growth was slow in relation to the vastness of France’s North American empire, the courageous King’s Daughters were the progenitors of millions of modern-day Franco-Americans, both in Canada and the United States.

The French were .very adventuresome. Their coureurs de bois, or frontier explorers, established a series of trading posts and commercial towns along the great interior waterways of North America. Starting with Quebec and Montreal on the St. Lawrence River, the French influence eventually spread through the entire Great Lakes region, penetrated the Ohio River Valley at Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh), and extended to the Mississippi Valley, where the outpost of St. Louis anchored the northern settlements and Mobile and New Orleans became French windows on the Gulf of Mexico. This far-flung empire of the Bourbon monarchy not only supplied raw materials to the mother country but also served to check the territorial encroachments of Protestant England.

The friction between England and France over the European balance of power and colonial ascendancy resulted in a series of wars that continued sporadically during the three-quarters of a century following England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, an event that marked the ouster of England’s Catholic king, James II. The last conflict, popularly known as the French and Indian War (1754-63), resulted in a sound defeat for the forces of Louis XV. The Treaty of Paris (1763) that concluded this “Great War for Empire” stripped France of her North American empire (except for two small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence) and placed the French colonists under English rule.

French Canadian culture certainly did not die with General Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham in 1759, but the collapse of the French Empire caused many French officials to return to their homeland. This exodus of civil authorities created a leadership vacuum. Faced with the prospect of English rule and the attempted imposition of the Protestant religion upon them, the rural French habitants looked to the clergy to preserve their religion, language, and culture. La foi et la langue became the twin pillars supporting French Canadian cultural persistence. The bond between language and faith became inseparable. To adopt the English tongue became synonymous with a surrender to Protestantism. Consequently, all those who learned English or assumed English surnames were not only considered defectors; they were thought to be lost souls as well.

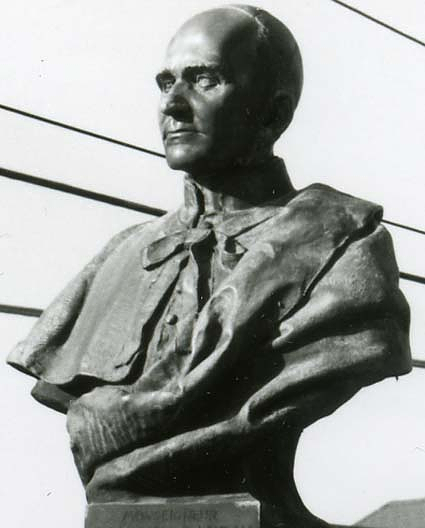

Sculpture of Monsignor Charles Dauray, 1934. Father (later Monsignor) Dauray helped to build Notre Dame du Sacre Coeur in Central Falls (completed in 1875). He then transferred to the Church of the Precious Blood in Woonsocket, where he served for 55 years. Under his direction, seven new parishes were created, as well as several schools and orphanages(Smithsonian Museum)

In 1774, as a result of British fears that the brewing revolution in the American colonies might spread to her newly acquired French subjects in Canada, Parliament in London passed the Quebec Act. This act granted religious toleration to the Catholics of that colony, extended the boundaries of Quebec province southward to the Ohio River, eliminated the antipapal oath of allegiance to the British Crown, and permitted a small degree of self-government. While slightly mollifying anti-British feeling, this opportunistic legislation did not win the loyalty of the French. In religious spirit, language, and culture, the habitants refused to be assimilated.

The French of Canada are a proud people. Their history is filled with a strong allegiance to Catholicism that has its roots with Champlain and his initial settlement. Like the Irish, the French Canadians have a national identity forged by a severe test for survival in their British-dominated homeland. The comparison extends further, for the French habitant and the Irish cottier shared a common socioeconomic lifestyle. They both came from an agricultural, background that sometimes bordered on the subsistence level; they raised large families; they migrated to escape economic deprivation; and they were clannish by nature. The Church of France had been the defender and tutor of Irish Catholicism after Henry VIII’s separation from Rome. The same strains of mysticism, moral rigor, and authoritarianism flowed through both churches to varying degrees. For both ethnic groups, religion and nationalism became a single entity from which they received the spiritual subsistence needed to lighten the hardships of a subjugated life.

Ironically, these two groups failed to coexist in harmony. The French-Irish friction was one of the most serious internal problems that the Diocese of Providence faced during the first sixty years of its existence. This strife can be best understood when viewed from an economic and cultural perspective.

Life among the habitants of Quebec became one of increasing hardship. The farmlands, exhausted by overuse, produced smaller crop yields. The problem of inheritance and land tenure accelerated the economic decline. When a father died, his farmland was subdivided among his surviving children. Because of this fragmentation of agricultural land and the bare subsistence farming it produced, many began to look beyond the Canadian borders for relief.

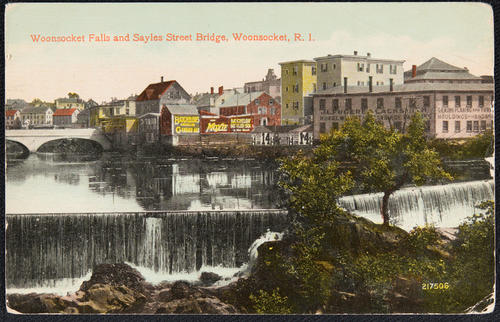

The trickle of what would become a flood of French Canadian immigrants to Rhode Island began in 1815. During that year Francis Proulx and his family settled in Woonsocket. Six years later the families of Prudent and Joseph Mayer chose northern Rhode Island as their new home. By 1846 a “statistical survey of Woonsocket” conducted by S. C. Newman revealed that 250 inhabitants in the Woonsocket area were of French Canadian ancestry in a total population of 4,856.

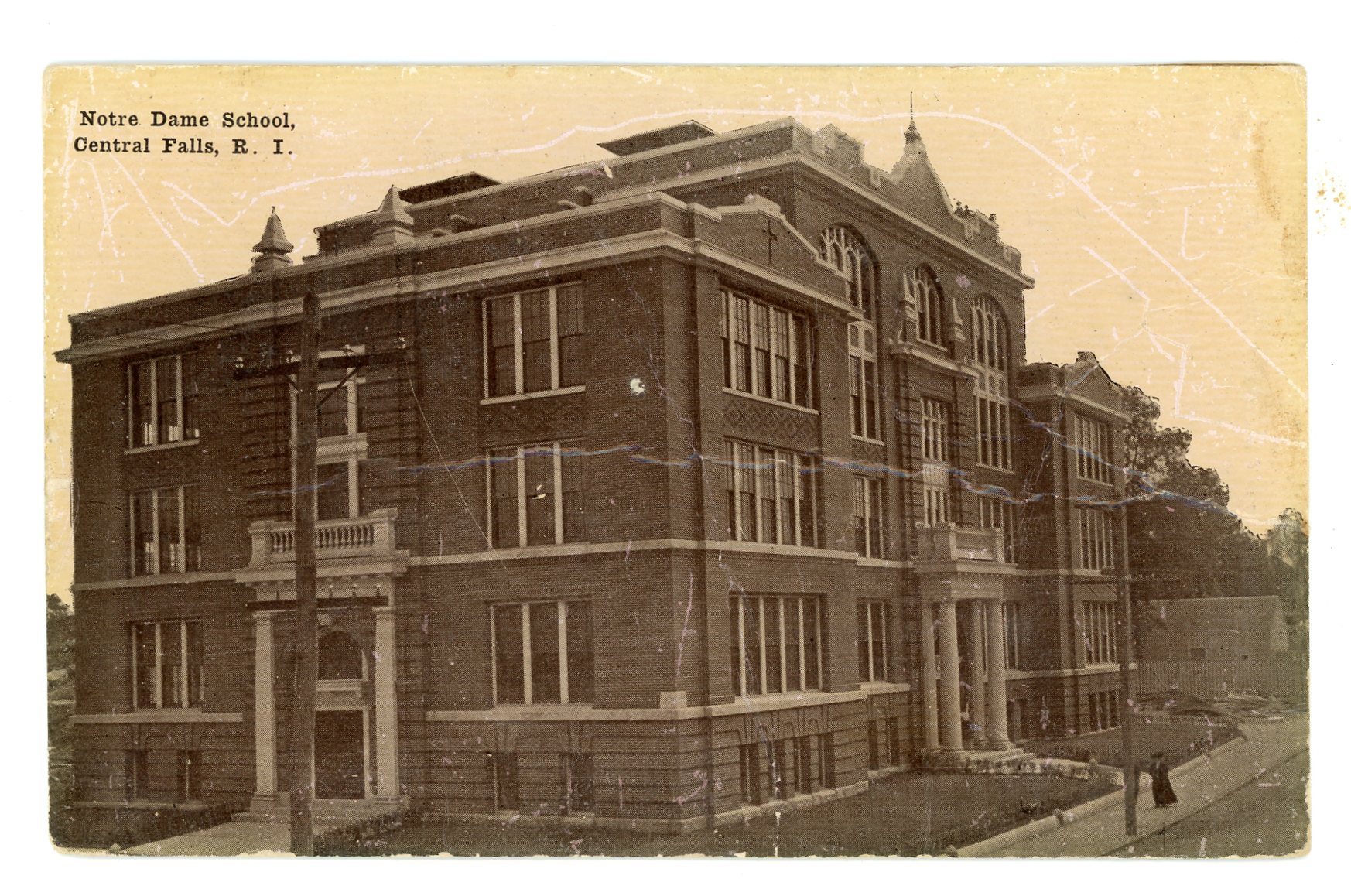

Notre Dame School in the parish of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, Central Falls. The Sisters of Mercy started the school in 1880. A French-Canadian order, the Sisters of St. Ann, assumed the teaching duties in 1892. (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Most of the new arrivals were responding to what some have called “the lure of the loom.” As early as 1810 Woonsocket textile entrepreneurs had opened the Social Manufacturing Company. Within a short period the clatter of textile shuttles could be heard along the banks of the Blackstone River. The continued expansion of the textile industry in Rhode Island prompted the mill owners to recruit the eager habitants of French Canada who were already experienced in the domestic production of textiles. With the coming of the Civil War, the need for manpower to replace those serving the Union cause became so acute that many New England manufacturers set up employment agencies in Quebec province.

For those seeking an escape from the privations of farm life, the promise of a steady job and good pay was too tempting to refuse. And for those with large families, children now became an asset as potential wage earners. Many left Quebec, never to return. Possessions and land were often auctioned off to provide train fare. Some habitants, however, envisioned their stay in America as a temporary one that would provide the means of insuring financial security when they returned to their homeland.

The reception of Franco-Americans in a strange land was often less than cordial. Willing to work a fifteen-hour day, six days a week, for a meager wage, the French Canadians represented a clear threat to the economic security of both Yankee and Irish mill hands. These economic fears partially explain the failure of the Irish to welcome the newcomers from French Canada. And since cotton and woolen manufacturing dominated the state’s economic scene well into the twentieth century, the basis for this ethnic tension was slow to be eliminated. In the late 1880s politics became another point of Franco-Irish friction when most habitants reacted to Irish antagonism by allying with their employers—the Yankee Republican industrialists.

French Canadian immigrants to Rhode Island retained that strong adherence to their faith, language, and customs that had sustained their cultural identity in English-dominated Canada, but even their mode of Catholicism clashed with that of their Irish coreligionists. In Quebec the parish church was the center of religious activity, and the higher echelons of Catholic authority exerted little, if any, control over their cures. Virtually all power was vested in the parish council, which usually consisted of three laymen and the parish cure, or pastor, who served as president. Canadian immigrants to America found a centralized Catholic church—a church whose power base lay not in the parish but rather with the bishop. After 1866 legal authority to transact the business of the parish in Rhode Island was vested in a parish corporation, but it was the bishop, not the pastor, who served as president. To a people accustomed to local control by French-speaking cures, this centralized church organization, dominated as it was by Irish prelates, represented a threat to religious traditions. The Franco-Americans not only belonged to a church; in a sense, they felt that it also belonged to them.

There were other novelties that caused the French Canadians to be uncomfortable in their new religious surroundings. Seat money and other offerings were levies to which they were unaccustomed because of the well-endowed status of their church in Canada. English-language sermons and confessions hampered them in the practice of their faith. The demand by the Franco-Americans for the preservation of their native tongue did not strike a responsive chord with many Irish priests who felt that rapid Americanization of foreign-born Catholics would dispel the Church’s foreign or alien image. Finally, the habitant missed the colorful and elaborate religious rituals that Irish priests, sensitive to Yankee criticisms of “popish pageantry,” often simplified or eliminated.

The anxieties that these differences created could best be relieved, and the spiritual needs of the migrants from French Canada could best be served, by the ministrations of French Canadian priests working within the framework of French Canadian national parishes. This became not only the desire but the demand of the transplanted habitants. Survivance, the maintenance of their culture, was threatened by les eglises irlandaises (the Irish churches).

By 1865 there were 3,384 foreign-born Rhode Islanders from “British America,” and a substantial majority of this number were people of French descent from Quebec. Five years later the federal census recorded 10,242 immigrants from this source. Woonsocket continued to be the population and cultural center for the state’s Franco-Americans, but the Blackstone Valley mill villages of Manville, Ashton, Albion, Slatersville, Central Falls, Pawtucket, and Marieville also attracted large numbers of habitants. Further to the south, the Olneyville section of Providence, the town of Warren, and the Pawtuxet Valley textile centers of Arctic, Natick, and Lippittsville were affected by the influx of Franco-American migrants. Clearly the time had arrived to recognize the special religious and cultural requirements of this rapidly growing Catholic community.

Finally, in 1872, Bishop Francis McFarland gave the French their long-awaited national parish by incorporating L’Eglise du Precieux Sang (Precious Blood). Although the church building itself was not completed until 1881, Precious Blood, in Woonsocket, is regarded as the Franco-American mother church. It was followed by Notre Dame du Sacre Coeur of Central Falls in 1873. The parishioners there, led by young, dynamic Father Charles Dauray, were the first to complete and occupy their church, dedicating that structure on October 2, 1875.

By 1880 the French Canadian community was also served by St. Jean Baptiste in West Warwick, St. James in Manville, and St. Charles in Providence. Fifteen more French national parishes would be established in the years that followed, for a total of twenty. Through the medium of the national church and its cultural ally, the French national society, the heritage of Rhode Island’s transplanted habitants was now secure.

[Banner Image: Precious Blood Church and Rectory, Woonsocket (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]

[This article by Patrick T. Conley was previously published, including in Patrick T. Conley, Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection: Public Addresses and Essays (East Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2002).]