Robert Emmet Quinn, named for the noble Irish patriot, led the political transformation of Rhode Island from Republican to Democratic ascendancy during the turbulent 1920s and 1930s. A similar shift occurred in neighboring Massachusetts, a state with comparable demographics. Historian J. Joseph Huthmacher in his highly regarded book Massachusetts People and Politics, 1919-1933 (Harvard, 1959) ably described that transition. Gerald H. Gamm later described it in The Making of New Deal Democrats: Voting Behavior and Realignment in Boston, 1920-1940 (1986).

Because of discriminatory flaws in Rhode Island’s constitutional system (which I have exposed in other writings), Rhode Island’s transformation was more difficult, intense, tumultuous, and bizarre than that of its neighbor. This subject also demands a scholarly, book-length analysis. I intended to write such a volume, but a multitude of diversions prevented me from realizing that goal. Had it been written, Robert Emmet Quinn would have played the starring role.

Cover page for a new book on Robert E. Quinn to be published by the Rhode Island Publications Society later this year. Patrick T. Conley’s two-part article on Quinn will appear in this book (Rhode Island Publications Society)

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Rhode Island experienced important demographic changes. It received a major influx of southern and eastern European immigrants from Italy, Portugal (including the Azores and Cape Verde), Greece, Armenia, Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Russia (mainly Jews), as well as Near Easterners from Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. This influx peaked in the years before the outbreak of World War I in 1914 and continued immediately thereafter until limited by the federal Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and, especially, by the National Origins Quota Act of 1924. Rhode Island’s diversity was facilitated by the Fabre Line, a trans-Atlantic steamship company. It brought 84,000 immigrants to the Port of Providence from 1911 to 1934, at least 11,000 of whom settled in Rhode Island.

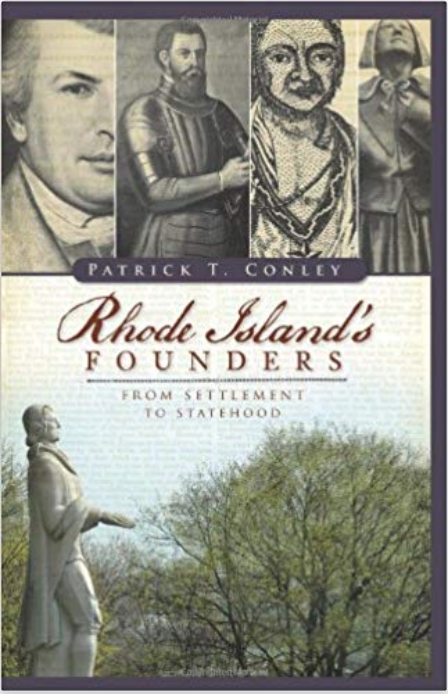

A photograph and description of Robert E. Quinn from the Brown University Yearbook for 1915. In those days, the writers of the background for each graduate took their tasks seriously (Harbor Foundation Research Library)

The economy also changed in the years after war’s end. The state’s burgeoning population suffered through a precipitous decline in the dominant textile industry while other areas of the country prospered. This decline was followed by the Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression of the 1930s.

Such demographic and economic shifts had profound political consequences. A dominant and conservative Republican Party, ascendant since the Civil War, controlled state government until the early 1920s. Providence business interests and rural politicians hailing from South County and the western farming towns along the Connecticut border led the GOP. It also had the allegiance of two large ethno-cultural groups–the Franco-Americans and the Italians–which regarded the Republicans as the party of industry, jobs, and what the GOP called “the full dinner pail.” Irish-American antagonism and resentment towards these newer arrivals also kept them from embracing the Irish-led Democratic Party, despite the fact that the Irish, French, and Italians shared a common religion. However, even within Catholicism there was friction, a story revealed by Rev. Robert Hayman in his detailed history of the Diocese of Providence and by Evelyn Savidge Sterne in Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence (2004) .

During the 1920s, the national Democratic Party moved from a rural to an urban orientation as Nebraska’s William Jennings Bryan gave way to New Yorker Alfred E. Smith. In addition, organized labor grew in strength and influence and was embraced in Rhode Island much more by the Democrats than by the business leaders who controlled the Republican Party.

After World War I, there was a national reaction to hyphenated Americanism because such groups as the German–and Irish–Americans were less than enthusiastic in their support of our ally England over Germany. A wave of 100-percent Americanism crested and the Klu Klux Klan revived, with this reincarnation more nativistic than merely racist. In Rhode Island most Irish-Catholic Democrats denounced these trends, whereas most Republicans (with U.S. Senator LeBaron Colt a notable exception) supported discriminatory immigration laws.

Vigorous pro-labor reforms, demands for constitutional change, the 1928 presidential campaign of Governor Al Smith of New York, a charismatic Catholic politician of Irish, German, and Italian ancestry, and the social programs of the New Deal during the Great Depression also combined to bring the newer immigrant groups into the Democratic fold. In addition, the willingness of the Irish to advance Franco-American leaders such as Felix Toupin of Woonsocket, Alberic A. Archambault of West Warwick, and Aime J. Forand of Central Falls, as well as young Italians from Providence such as Luigi De Pasquale, Louis W. Cappelli, and John O. Pastore caused a major shift in the political allegiance of both the French and the Italians.

It was against this demographic, economic, cultural, and political backdrop that Robert Emmet Quinn, also referred to as “Fighting Bob,” played his leading role in the time from the June 1924 legislative filibuster to his departure from the office of governor in January, 1939.

However, any account of Robert Quinn’s rise should begin with a profile of his uncle, mentor, and law partner, the equally volatile and irrepressible Colonel Patrick Henry Quinn. His parents, Peter and Margaret (Callahan) Quinn, displayed their patriotism for America and its traditions by naming their son for the fiery Virginia Revolutionary War patriot famous for his defiant statement, “Give me liberty or give me death!”

Patrick Henry Quinn was born in 1869 in the Warwick mill village of Phenix. He followed the successful path of many ambitious Irish-Catholics by interlacing labor union activity with legal training and Democratic Party activism within the even larger framework of his ethnicity and religion. He was a masterful speaker and belonged to most of the civic clubs and organizations of his day.

Quinn, with a grade school education, entered the Clyde Print Works as a finisher and remained there for nine years. He spent his childhood, like so many others in the state, as a child laborer. But like the proverbial cream that rises to the top, Quinn studied life through observation and by reading books at the end of the work day. He found his initial success as a member of the Gilded Age’s most powerful labor union, the Knights of Labor, which had a meteoric rise in Rhode Island. Quinn achieved the union’s highest state ranking, District Master Workman, just as the Order began to decline in the 1890s.

In his early twenties Quinn secured a job as bookkeeper and salesman at the printing house of William R. Brown and Company and studied law under his mentor Edward L. Gannon. He formed a partnership with Willard Tanner and Gannon after his entrance to the bar in August 1895.

In November 1897, this young lawyer wed Agnes Healey of Providence who died in February 1907 after only ten years of marriage. Patrick took a second wife, Margaret M. Conners of Providence, on July 22, 1909 by whom he had one son, Thomas Henry.

Quinn helped to create the state’s thirty-ninth municipality, the densely populated industrial town of West Warwick. When it peeled away from Warwick in 1913, Quinn served as first president of the new town’s council. The Rhode Island General Assembly approved this division of Warwick, with Quinn its leading advocate, in order to safeguard Republican ascendancy in that original town, the eastern part of which was predominantly rural.

Quinn remained a solo legal practitioner for many years prior to forming a partnership with Charles H. Keenan. He was an excellent trial attorney known both for his legal acumen and oratorical skills.

Patrick Henry was the consummate politician. His litany of political positions in Warwick and West Warwick was unmatched. In 1893, he began his decades-long participation in the state convention of the Democratic Party. Ten years later he became a senior aide to the Democratic reform Governor Lucius Garvin, who conferred upon Quinn his cherished title of colonel.

In 1900, Patrick became a delegate to his first of many Democratic National Conventions and, in 1914, he was the unsuccessful standard bearer of his party in the race for governor. Clearly Robert Emmet Quinn could not have chosen a more influential trail-blazer for his own career in politics than when he became his uncle’s law partner.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Bob Quinn was born in the mill village of Phenix (then part of Warwick) on April 2, 1894, as the son of Mary Ann (McCabe) Quinn and the colonel’s brother Charles. His grandfather Peter Quinn was a stone mason whose specialty was building railroad bridges.

As a young boy, Robert went to St. James Parochial School in the village of Arctic and then to the original Warwick High School when it was located in present-day West Warwick. Because he was a brilliant student, he was able to attend Brown University from which he graduated in 1915. He commuted to Brown each day by train from the mill village of Clyde where his uncle lived. After graduating with honors Robert enrolled at Harvard Law School. However, his studies were briefly interrupted by World War I. He served as a volunteer in the area of diplomatic intelligence in both England and France, earning the rank of captain. At war’s end, he resumed his studies at Harvard and received his law degree in 1920 at the age of twenty-four. On August 3, 1923 he married Mary Carter.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The politically chaotic decades of the 1920s and 1930s in Rhode Island witnessed a major transition from Republican to Democratic control in state government. These two decades of transition did not have an auspicious beginning. In fact, the elections of 1920 portended a continuation of Republican dominance in state affairs. Both the Republican presidential candidate, Warren G. Harding and the GOP’s gubernatorial candidate, Franco-American Emery J. San Souci, who managed a family department store in the Olneyville section of Providence, won by huge margins. These victories offset such recent Democratic surges as the election of Peter Gerry to the U.S. Senate in 1916, the victories of Congressman George F. O’Shaunessy, and the strong showing of West Warwick’s Alberic A. Archambault in the gubernatorial election of 1918, although Archambault, the first Franco-American endorsed for state office by the Democrats, lost that race by a vote of 42,682 to 36,031. Conversely, in 1920 the Republican margin was nearly two-to-one. In that contest San Souci was nominated by the GOP to hold the Franco-American vote. This Providence businessman succeeded admirably, defeating the former Cranston Democratic mayor Edward M. Sullivan 109,138 to 55,963. The much-enlarged electorate was due to two major factors: the presidential campaign and the beginning of women’s suffrage. The margin of victory was also due to two main factors: dissatisfaction of the Irish and Germans with Wilsonian foreign policy and a far more effective mobilization of the women’s vote by Republicans. The Democrats in 1920 seemed doomed to perpetual minority status. Like the globe, they were flattened at the polls.

Newspaper cartoon from the Pawtucket Star, Nov. 1936, showing three key Democratic leaders who spearheaded the Bloodless Revolution of 1935: Robert E. Quinn (center), Theodore F. Green (right), and Thomas P. McCoy (left) (Russell DeSimone Collection)

For the Democrats, however, the 1920 election was merely the darkness before the dawn. Three incredible blunders by local Republicans in 1921-22 caused the GOP to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. These events happened rather rapidly, right in the wake of the Republican landslide of 1920.

Two of these politically damaging actions were related to labor issues. In 1921 and 1922, severe wage cuts caused by post-war deflationary trends were imposed by mill owners upon the workers in the local textile industry. These wage cuts hit the Franco-American mill workers hard.

In 1921 the textile mill owners attempted to combat the postwar deflation by imposing a 22 ½ percent wage cut on their employees. Used to such wage manipulation in previous deflationary periods, the workers acquiesced. In 1922, however, as economic conditions worsened, the owners poured salt on the workers’ wounds when they decreed an additional 20 percent wage cut and increased the weekly hours of work from forty-eight to fifty-four. Such harsh measures caused rebellion, and angry operatives struck the mills in the Blackstone and Pawtuxet Valleys. When violence threatened, Yankee Republican leaders pressured Governor San Souci to call out the National Guard. An ensuing skirmish between these citizen soldiers and Pawtucket demonstrators left one mill hand dead and fourteen wounded.

Despite such use of force, the workers remained adamant. Employers also sought and secured anti-labor injunctions and evicted strikers from their company housing, despite the efforts of the Quinns to defend them in court. By late 1922 the Amalgamated Textile Workers Union, operating in the Pawtuxet Valley, and the AF of L–affiliated United Textile Workers toiling in the Blackstone Valley had averted the second cut and actually regained some of the first wage reduction. On the workers’ demand for a forty-eight-hour week, however, management remained unyielding. A forty-eight-hour bill was sponsored in the General Assembly by the minority Democrats, but the Republicans defeated it, despite massive popular demonstrations in its favor. Not until 1936, after the Democrats had seized power in the state, did the legislature pass a forty-eight hour law.

The Republican administration’s use of the National Guard against the workers, together with the GOP’s opposition to the forty-eight-hour bill, prompted a large-scale defection from Republican ranks by Franco-American workers. This rift in the old political and economic alliance between the Yankee Republican mill owners and their Franco-American work force was quickly exploited by Irish Democrats.

In addition to these two economic blunders the Yankee Republicans, influenced by the pervasive 100-percent American movement spawned by the new immigration and by the opposition of some so-called “hyphenated Americans” to U.S. involvement in World War I, enacted Chapter 2234 of the Public Laws of 1922.

Frederick Peck, the Republican national committeeman and the boss of the Republican Party as successor to General Charles R. Brayton, sponsored this law. The statute’s most controversial provision (Section 11) required all instruction in private schools, including Catholic parish schools, to be in English. The law specified that “the state board of education shall approve a private school only when . . . the instruction in such school in all studies, except foreign languages and any studies not taught in public schools, is in the English language.” The novelties here were State Board of Education supervision of this particular requirement and state enforcement of it. A similar requirement, inspired by the nativistic American Protective Movement (APA), had been on the statute books since 1893, but it placed control and supervision in the hands of local school boards. Therefore, French cities such as Central Falls and Woonsocket ignored it. As a matter of fact, it was not unknown for French priests to serve on and to even chair these local school committees in the French community. The French considered the Peck Act’s mandate of state supervision to be a direct assault on the Franco-American cultural trinity–la langue, la foie, et la patrie (the language, the faith and, their attachment to their native Quebec). The French-Canadians regarded their language not only as a principal means of preserving their faith but also their cultural identity in what many of the somewhat insular habitants considered an alien environment here in the United States.

In 1922, the Democratic political campaign strategy focused upon these three issues: the textile strike, the Republican repudiation of the 48-hour law, and the Peck Act. As a further slight to the previously loyal Republican French, San Souci was dumped in favor of Yankee businessman Harold Gross, who owned a large insurance and real estate company. These events set the stage for a Democratic comeback, with French-Canadian leader Felix Toupin as the candidate for lieutenant governor and William S. Flynn of South Providence, as the gubernatorial nominee. In the election of 1922, Gross polled 74,224 while Flynn garnered 81,935 and won by a plurality of 7,211. After the debacle of 1920, when the Democratic candidate had lost by over 53,000 votes, this was the greatest comeback since Lazarus. The Democratic tsunami brought with it a new, young Democratic senator from West Warwick, Robert Emmet Quinn.

The election of 1922 was a highly significant breakthrough in Rhode Island, but the Democrats, at least at first, could not stand success. They regarded the election as a mandate for constitutional reform, and so they set out to devise ways to reapportion the Senate to lessen the rural influence there and also to repeal the Bourn Amendment with its property taxpaying requirement for voting in city council elections. They hoped to accomplish these reforms by way of a constitutional convention, although, they would have been satisfied with amendments to the constitution.

The Democrats went about their work in a very determined and, in some respects, a scandalous way. Because they had gained seats in the Senate, although they were still a minority, they believed that by filibuster and persistence, they could force the rural Senate majority into agreeing to their bill which allowed for a referendum on the convening of a convention.

On June 17, 1924 at 2:00 p.m. this Democratic effort reached its climax. At that stormy session the Democratic minority, led by Senator Robert Quinn and Lieutenant Governor Felix Toupin, the presiding officer, staged a marathon filibuster to force Republicans to pass a constitutional convention bill that had already cleared the Democratic House. Toupin’s strategy was to wear down some of the elderly Republicans and then call for a vote on the question when they snoozed or strayed.

In the forty-second hour of the filibuster, as the vigilant Democrats awaited the success of this scheme, Republican party managers authorized some thugs imported from Boston to detonate a bromine gas bomb under Toupin’s rostrum. As the fiery Woonsocket politician keeled over unconscious, senators scrambled for the doors. Within hours, most of the Republican majority was transported across the state line to Rutland, Massachusetts, where Toupin’s summons could not reach them. There they stayed (Sundays excepted) until a new Republican administration assumed office in January 1925. Ironically, the defeat of the Democrats in the 1924 state elections was due in part to the fact that the Providence Journal wrongly accused them of the bombing. In that year the newspaper had much to gain from discrediting the Democrats, because Jesse H. Metcalf, brother of the Journal’s president, was the GOP candidate for U.S. Senate in the fall election.

To stem the defection of Franco-Americans from the Republican Party, Aram Pothier was summoned from retirement to battle Felix Toupin in the 1924 governor’s race. With the Democrats unjustly blamed for the stink-bomb incident, Pothier and Metcalf won decisive victories, as did most other GOP candidates. The turmoil that convulsed the state legislature in its 1924 session prompted the victorious Republicans, who gained decisive control of that body in the Fall elections, to institute checks against the potential for such disruptions in the future. When the new legislative session opened in January 1925, the Republicans promptly sponsored a bill that created a Department of State Police. Rising violence in labor disputes and the need to enforce a statewide auto code were also motivating factors in the establishment of this uniformed statewide law-enforcement agency.

Shortly after the passage of the state police statute on April 2, 1925, Governor Pothier appointed Everitte St. John Chaffee of Providence as the department’s first superintendent. Chaffee, a military man who had compiled a distinguished World War I record as an officer of the 25th “Yankee” division, was given comprehensive administrative authority over the new agency, a power that all subsequent state police colonels have since wielded.

Rhode Island’s political turbulence in 1924 was matched on the national level by the fight over control of the Democratic Party and its policies. Colonel Patrick Henry Quinn was chairman of the Rhode Island delegation to the Democratic National Convention held in New York’s Madison Square Garden in late June and early July. That convention staged the biggest brawl in the history of the Garden, a venue famed for its heavyweight championship boxing bouts. According to one commentator, “rural nativism and urban rowdyism clashed in a head-on collision.” Once small aspect of that “rowdyism” was a direct and hostile confrontation between Colonel Quinn and Democratic Party leader William Jennings Bryan.

In 1896, Bryan and his Populist followers lost the presidential election to William McKinley and his “full dinner pail” promise to American workers. However, the rural, agrarian Bryanites gained control of the Democratic Party and sought to implement its farm-oriented platform.

In 1924, that control was challenged by the presidential candidacy of colorful New York governor Alfred E. Smith, described by his biographers as the “Hero of the Cities.” Smith’s bid for the nomination was contested by the Bryan-backed William Gibbs McAdoo, a competent Tennessee-born attorney, who was also Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of the Treasury and the president’s son-in-law. Smith and McAdoo battled for a fortnight through 103 ballots before agreeing to Virginian John W. Davis as a compromise nominee. A low-point of the convention was the refusal of the party’s rural wing to condemn the revived Ku Klux Klan. This platform plank, backed by Smith, was voted down by the narrow margin of 546 to 542. At this time the Klan had about four million members who opposed immigrants, especially Catholics and Jews. The new Klan was no longer a purely Southern phenomenon; it even conducted cross-burnings in Rhode Island.

Smith, who had been nominated as “the Happy Warrior” by Franklin D. Roosevelt, gradually assumed the leadership of the Democratic Party. By 1928, his pro-labor, anti-Prohibition positions made the Democratic Party much more palatable to Rhode Island’s ethnics than the “dry” and increasingly nativistic GOP.

After the 1924 General Assembly debacle, Bob Quinn stepped aside as West Warwick’s senator in favor of his fellow Democratic townsman Alberic Archambault. In that year the ambitious young attorney became Toupin’s running mate as the Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor. He lost that race decisively and failed again in his 1926 bid to become attorney general. The lingering effects of the 1924 debacle and the presence of popular Aram Pothier at the top of the Republican ticket were too much to overcome. In 1928, Quinn ran successfully for West Warwick’s Senate seat when Franco-American leader Alberic Archambault made his second bid for governor in 1928 on a slate headed by Al Smith.

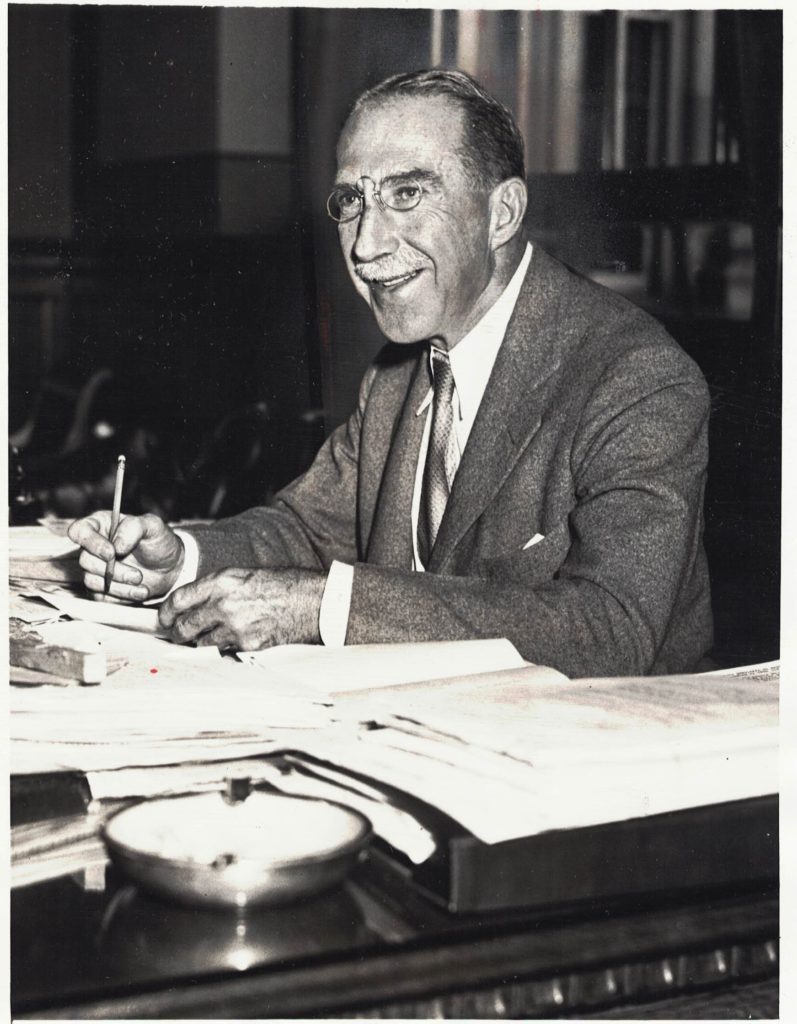

Robert E. Quinn’s official portrait as governor of Rhode Island (1937-39) by J. C. Allan Carr, hanging in the Rhode Island State House (Rhode Island State House Collection)

For the people of Rhode Island, the presidential campaign of 1928, pitting Democrat Al Smith against Republican Herbert Hoover, was among the most exciting ever. Smith appealed to the Catholic ethnic vote, and his candidacy hastened the conversion of local Italians, French Canadians, and Polish to the Democratic Party. When he beat Hoover statewide by a plurality of 1,451, the New York governor became the first Democratic presidential candidate to poll a majority of the state’s popular vote since Franklin Pierce turned the trick in 1852.

In what the Republican-oriented Providence Journal described as “the most stirring political campaign since the Civil War,” Smith barnstormed the state in October, creating pandemonium. According to one newspaper account, “fire engines screeched, band instruments blared, torpedoes tossed by youngsters exploded, tickertape floated in a sinuous maze from the windows of all buildings, automobile horns blasted, shrill whistles and locomotives screamed, confetti and shredded newspapers descended in blinding drifts, and an airplane marked with words of welcome swooped an aerial salute as the governor’s procession passed slowly along.”

Unfortunately for Archambault, who lost his gubernatorial race to attorney Norman Case by 8,154 votes, ethno-religious controversy in Rhode Island dissuaded some of his fellow Franco-Americans from supporting the Irish-led state party. A dispute, known as the Sentinellist Controversy, pitted Bishop William Hickey and his Irish hierarchy against certain Franco-American dissenters. The bishop demanded centralization of his diocese in the chancery, whereas some French leaders preferred the Quebec tradition of parish autonomy. This dispute, marked by the excommunication of Sentinellist leader Elphege Daigneault, might be called the darkness just before the dawn in French-Irish cultural relations. It began to subside in the aftermath of the 1928 election and evaporated by 1933 with the death of the autocratic Bishop Hickey and the appointment of a conciliatory successor, Francis P. Keough.

The 1928 election not only marked Bob Quinn’s return to the Senate, but it also resulted in the ratification of two major amendments to the Rhode Island Constitution. They could be viewed as Republican concessions to deter major constitutional reform via an open convention. Despite the cumbersome amendment procedure–passage by two successive General Assemblies with a general election intervening and a three-fifths vote of the electors–Articles of Amendment XIX and XX became law.

Article XIX, allowing one senator to a municipality for every 25,000 voters, was ratified by a margin of 63,202 to 19,754. It gave Providence four senators including a pioneer–Elizabeth Ahearn O’Neill. It was a small step in eroding rural control of the upper chamber.

Article XX, by removing the property qualification for voting in city council elections, prepared the way for the Democrats to control the powerful city councils, which in turn controlled municipal jobs. It was ratified by a vote of 62,263 to 20,107. In Providence, especially, control of the patronage allowed the Democrats to entice many in its large Italian population to abandon their traditional allegiance to the GOP.

In 1930, Republican governor Norman Case narrowly won reelection over Theodore Francis Green (112,070 to 108,558), but Quinn easily retained his Senate seat. Two years later, on his third try, Green prevailed, even though he had backed the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt over Al Smith. Fortuitously Green chose Bob Quinn as his running mate. Both were easily elected, and Quinn, as lieutenant governor, became the presiding officer of the Senate.

The 1934 state elections produced the same result, and the stage was set for the Bloodless Revolution. However, before that repeat victory, the administration of Green and Quinn had to survive a major economic upheaval–The Great Textile Strike of 1934. That incident has been called by one labor historian, “the most dramatic single illustration of the tragic long-term decline of the textile industry, the economic base supporting much of Rhode Island’s working class since the middle of the nineteenth century.” In ten years–1923 to 1933–the number of cotton textile wage earners in the state shrunk from 33,933 to 13,077. Despite the efforts of Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration (NRA), the textile industry remained in distress and worker complaints of wage cuts, plant shutdowns, and sudden layoffs led to rising militancy. At this juncture the United Textile Workers Union (UTWU) called upon its members nationwide to strike.

On September 3, 1934, the scheduled walkout began to affect mills throughout Rhode Island. By the second week of the strike, tensions between workers and owners erupted into open conflict in the Social District of Woonsocket and the Lincoln village of Saylesville. On September 10, rioting and physical destruction of property reached such levels that Governor Green mobilized the National Guard and made a request (unanswered) for federal troops. The Journal headline on September 12 told the tragic story: “Guardsmen fire in Saylesville; pickets, sympathizers, and hoodlums run wild in Woonsocket, destroy property in Social district; six shot” (one of whom died). Fortunately, the rioting ended swiftly on September 13 and order was restored. Ten days later, after President Roosevelt appointed a national fact-finding commission to address textile workers’ grievances, the UTWU called off the strike.

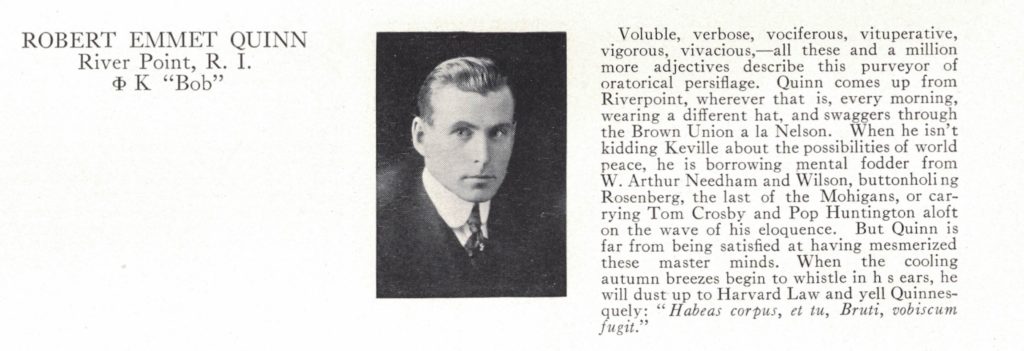

Theodore F. Green served as governor of Rhode Island two terms, from January 3, 1933, to January 5, 1937 (Russell DeSimone Collection)

On October 2, 1934, the Democrats renominated Green for governor, and one month later he won by a plurality greater than the one that had elected him in 1932. The use of National Guardsmen in 1922 had severely hurt the GOP; twelve years later the deployment of similar force in a labor uprising had no detrimental effect upon the Democrats. This anomaly may be explained by several factors: workers were well aware of Green’s pro-labor sentiments and the labor planks in the 1934 Democratic platform; the governor acted only when violence had become otherwise uncontrollable; and he managed to convince most workers that the rioting and destruction of property were the handiwork of Communist agitators. Somehow Green succeeded in projecting a dual image, both as a protector of public order and, like Quinn, as a long-time friend of the working class. The latter image, at least, was reinforced by a litany of social legislation enacted by Green and his party once they gained control of state government via the Bloodless Revolution of January 1935.

In the aftermath of the 1934 state elections, Rhode Island’s political transformation appeared complete. Using ethnic balancing, a tactic that would endure for several decades, all of the newly-elected general officers were Democrats–Governor Green (Yankee), Lt. Governor Quinn (Irish), Secretary of State Louis Cappelli (the first Italian-American general officer originally selected in 1932), Attorney General John P. Hartigan (Irish), and General Treasurer Antonio Prince, a Woonsocket Franco-American.

Rhode Island’s two congressmen were Irish Democrats–Francis B. Condon and John M. O’Connell. Yankee millionaire Peter Gerry defeated incumbent Franco-American Republican Felix Hebert in that year’s race for the U.S. Senate. Gerry won the Franco-American city of Woonsocket by a vote of 10,056 to 4,870–a more than 2-to-1 margin.

Local Democrats even exerted influence on the national scene when Brown University and Harvard Law School graduate Thomas G. “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran became a leading draftsman and lobbyist for much of the legislation that is now labeled as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Corcoran, a Pawtucket native, was recommended to FDR by Green and Harvard Law School professor Felix Frankfurter, a future Supreme Court justice. Corcoran became a close friend of Roosevelt, wrote many of his speeches, and coined FDR’s famous phrase “rendezvous with destiny.”

After the 1934 balloting, even control of the Senate seemed within the grasp of the insurgent Democrats. They were poised to take this bulwark against reform that Irish-born U.S. Representative, George F. O’Shaunessy who had become Rhode Island’s first Catholic member of Congress in 1911, derisively called “a malign influence exercised over state government by the abandoned farms of Rhode Island.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Bloodless Revolution of January, 1935 was not a spontaneous uprising; it was a well-planned coup (as detailed by Quinn in his interview with Matt Smith). A dozen Democratic leaders orchestrated the events of January 1 with Quinn the conductor.

In late November and early December, 1934 the votes for the 42 Senate seats were tallied and the preliminary count gave the Republicans a 23 to 19 edge. However, the Democrats alleged voter irregularities in three towns ostensibly carried by the GOP–Coventry, Portsmouth, and South Kingstown. Upon investigation, the chicanery in Coventry was so blatant, that the Republican-dominated State Returning Board reversed the result leaving the “final” count at 22 to 20 in favor of the Republicans.

However, Quinn was convinced of fraud in both Portsmouth and South Kingstown. As the incumbent presiding officer of the Senate by virtue of his 1932 victory, he invoked a constitutional power under Article IV, Section 6 to have the Senate itself conduct a recount in the two disputed districts. To that end, he appointed a three-member Senate committee composed of two Democrats and a moderate Republican.

Confident of the results of that inquiry, Quinn, Governor Green, Mayor Tom McCoy of Pawtucket, First Assistant Attorney General William W. Moss, Providence Representative Edmund Flynn, and several others met to draft the revolutionary scenario.

When the Senate opened on New Year’s Day 1935, Quinn swore in all of the senators-elect except for Republicans B. Earle Anthony of Portsmouth and incumbent Wallace Campbell of South Kingstown. This duo sat in their assigned seats with flowers on their desk, but Quinn ignored them. This procedure left the Senate divided 20 to 20 with Quinn presiding. As in 1924, several Republicans tried to leave the chambers to prevent a quorum but Quinn had prepared warrants for their detention and the state police complied.

The state police presence and compliance had been facilitated the previous January when Green and Quinn ousted unpopular Colonel Everitte St. John Chaffee in favor of their own candidate to lead the state police, Edward J. Kelly of Providence. Kelly was confirmed by the Senate in a voice vote when Quinn, as presiding officer, refused requests of the Republican majority for a roll call ballot. At that session Republicans had 27 senators compared to only 14 Democrats and 1 independent. Because of a GOP omission in creating the state police, its colonel was not covered by the Brayton Act.

With the Republicans restrained, Secretary of State Louis Cappelli supervised a recount. That tally overturned the election results in both towns and gave victory to Portsmouth Democrat Joseph P. Dunn and South Kingstown Democrat Charles A. White, Sr. The new line-up was now 22 to 20 in favor of the Democrats, thanks not only to Quinn’s maneuvers, but also to the 1928 constitutional amendment that had allowed Providence four Senate seats.

With a comfortable margin in the House of 58 to 42 and the consequent 80 to 62 control of the Grand Committee of the House and the Senate–the body that then chose Supreme Court justices–Democrats implemented their revolution by enacting the five major bills that their cabal had prepared in anticipation of gaining Senate control. These measures were introduced and passed by the eager Democrats in rapid-fire succession.

The first bill, not as important as some of the others, vacated the office of Sheriff Jonathan Andrews of Providence County and all the patronage jobs that went with it. The second vacated the five judgeships of the state supreme court. The five Republican justices on the court were granted large pensions on the condition that they resign their offices by noon the following day. They did so. The first bill passed by a voice vote, the second by a roll call.

The third bill passed by the insurgents wiped out the Providence Safety Board and gave Governor Green the power to name a public safety director for the city. This Providence Safety Board situation was the most notorious example of Republican interference in the affairs of those municipalities that were under Democratic control. At that time the state operated under a theory of local government known as the “creature doctrine” whereby local communities were mere creatures of the General Assembly with the legislature having virtually absolute power over them. It was the custom of the Republican-controlled state government to interfere quite frequently in the local affairs of cities that were tending towards the Democratic Party.

The fourth bill abolished the office of finance commissioner and created a combined office of state budget director and state controller and placed the budgetary powers under the governor. Prior to this act, the finance commissioner, appointed by the Senate, had control of the state budget. The governor had no budgetary power other than to veto the entire budget, because he lacked an item veto (and still does). Control of the finance commissioner, a position then held for over a decade by Republican state party chairman Bill Peck, was another method by which the GOP Senate was able to maintain its dominance in state affairs under the 1901 Brayton Act.

The last bill, Chapter 2188 of the Public Laws of 1935, was the longest. It merged some 80 state commissions controlled by the Senate into eleven executive departments, and it repealed the Brayton Act, not by name but by repealing all acts “inconsistent” with the reorganization law. The seven departments not headed by an elected general officer were to be headed by a director who would be appointed by the governor and hold office “at the pleasure of the governor.”

From the time that the Senate convened to hear the report of the special committee on the recount at 7:32 p.m. to the adoption of the fifth measure, which repealed the Brayton Act and reorganized state government, only fourteen minutes elapsed. The House quickly approved the measures by roll call votes along a straight party line, and Governor Green immediately signed them into law. Next the Grand Committee met to fill the vacancies of sheriff and the justices of the state supreme court, appointments already agreed upon in advance. Then Green was sworn into office as governor for a second term. Finally, at 12:05 a.m. the governor read an abbreviated inaugural address that contained recommendations for much that had already occurred and invoked “the spiritual presence of the patron saint of the Democratic Party in Rhode Island—Thomas Wilson Dorr.”

Irwin Levine notes in his biography of Green that when the Grand Committee was filling the new vacancies, Ed Higgins, Green’s administrative assistant, used the Governor’s car to deliver letters to Providence Safety Board members, Everett St. John Chaffee, George T. Marsh, Michael Corrigan. They were informed that they were removed from office and were, therefore, no longer state officials. On the following day, the new supreme court jurists, except for Congressman Francis B. Condon who was in Washington, were sworn into office with Edmund Flynn of South Providence as chief justice. With that ceremony the Bloodless Revolution of 1935 was over.

Although dwarfed by the controversy caused throughout the country by the Dorr Rebellion, this bold Democratic coup did not escape national attention. One humorous response is worthy of note. In Chicago, Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick, the conservative and aristocratic publisher of the Chicago Tribune, when hearing of the Rhode Island revolution, hauled down the giant American flag in the lobby of the Tribune building and expelled Rhode Island from the Union by cutting out one star. Later in the day, when he was informed that mutilation of the American flag was punishable by a fine of up to one hundred dollars or by thirty days in jail, McCormick reluctantly ordered the star replaced, thus restoring Rhode Island to the Union.

[Banner Image: Newspaper cartoon from the Pawtucket Star, Nov. 1936, showing three key Democratic leaders who spearheaded the Bloodless Revolution of 1935: Robert E. Quinn (center), Theodore F. Green (right), and Thomas P. McCoy (left) (Russell DeSimone Collection)]