Rhode Island once had a mass transit system that crisscrossed the state. Workers took horsecars and electric streetcars from their tenements to the mills and factories during the week. On weekends they boarded trolleys for pleasant rides to parks and amusement centers.

Most workers in those days led hard lives. The motormen and conductors who operated the streetcars shared the same miserable lot as their passengers. Like other employees, the carmen formed unions. They rebelled against low wages, long hours, and poor working conditions. They established a local of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America in 1894. The Union Railroad Company broke the union that time.

Small businessmen in downtown Pawtucket provided wagons to the strikers so other workers could get around and still patronize local stores. All voluntary fares went to the strike fund.

Several years later in 1901 the streetcarmen began organizing again. They asked for a union shop, $2.25 for a ten hour day, and arbitration of all grievances. The company, mostly owned by powerful United States Senator Nelson Aldrich, refused to negotiate. Even after the Rhode Island legislature passed a bill outlawing more than ten hours of work a day, management refused to comply and labeled the union an “outside and irresponsible authority.” Things were coming to a head.

On June 4, 1902, the carmen struck. Seven hundred workers went out. Only 250 old timers, who made 50 cents a day more than the younger workers, stayed on the job with a handful of company pets. Service was cut in half and few streetcars ventured out at night. The company charged that: “This strike has been brought about by professional agitators who go from city to city sowing seeds of discontent, endeavoring to create dissatisfaction between the employee and the employer.”

The passengers thought differently. There was a sense of working class solidarity in those days and passengers felt great loyalty to the motormen and conductors. Most citizens also despised the streetcar company for lousy service and the lack of transfers. The Union Railroad had a few powerful friends: the police, the courts, and most politicians.

On June 5, 1902, the strikers paraded in downtown Providence and were cheered by 20,000 onlookers. A riot broke out. Mill workers, middle class folks, and college kids supported the strikers by stopping the streetcars. For a few days, strikebreakers were afraid to work on the trolleys until police finally got the upper hand.

The action soon shifted to Pawtucket where hundreds of mill hands gathered nightly to jeer at the scabs. The mayor of the city, John Fitzgerald, backed the strikers. When the company asked for police protection, Fitzgerald replied: “Our police force is not at the beck and call of any corporations who feel they are entitled to special escort service.”

Violence continued as strike sympathizers blockaded trolleys, showered them with rocks and debris, exploded dynamite, and even shot at the streetcars. Women often took the lead in this street warfare. State marshals who were sent to Pawtucket to protect the cars were attacked; eighteen were injured in one night alone. Governor Kimball then sent in 1,000 state militiamen with Gatling guns and cavalry.

The greatest strength the strikers had in the face of this military force was their sense of community. Thousands of workers made small donations to the strike fund and boycotted the cars. Trolleys ran almost empty in the Blackstone Valley. Workers wore “we walk” ribbons in solidarity. Union members caught riding on streetcars were fined by their locals while parents encouraged children to harass teachers who violated the boycott.

Strikers also participated in sports events, picnics, and mass rallies. Neighborhood businesses provided wagons to the strikers to transport customers. Shopkeepers also refused to service any scabs. One landlady, for example, couldn’t purchase groceries because she put up a strikebreaker. A father in West Warwick dragged his son, who was a scab motorman, right off the trolley.

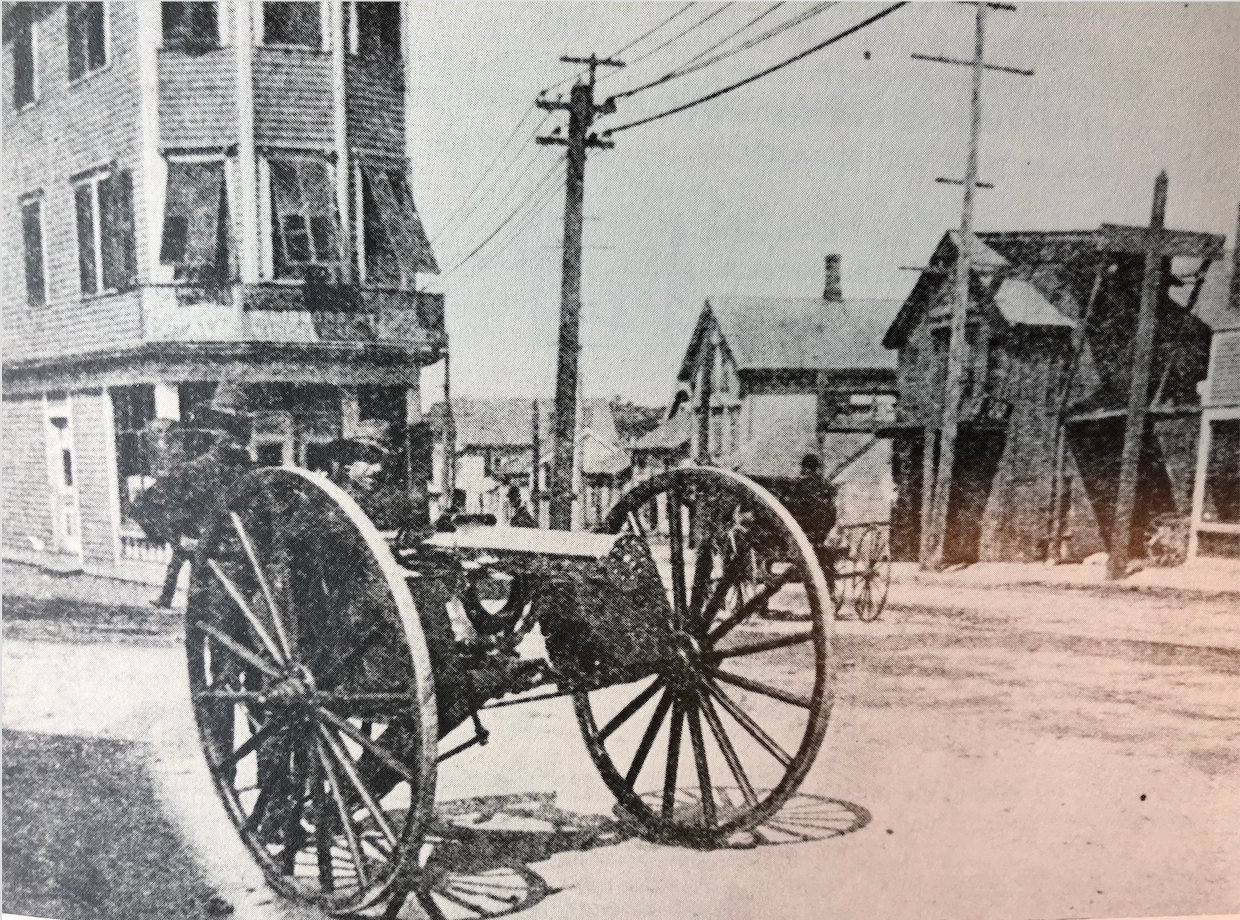

Gatling gun stationed on East Avenue in Pawtucket. Governor Charles Dean Kimball sent the militia into Pawtucket, but the troops, with many strikers in their ranks, sympathized with the union.

Meanwhile, police arrests and harsh sentences by the court were dampening enthusiasm. Also, with the exception of the Blackstone Valley, streetcars were operating on a regular basis. The militia did not withdraw from Pawtucket until June 25 and, in a gesture of respect to the strikers, left on a steam train rather than a streetcar operated by a strikebreaker.

The Rhode Island Supreme Court finally ruled that the ten hour law was constitutional, but the company refused to obey and appealed to the federal courts. A weakened union gave up in early July. Some strikers regained their jobs, but lost their seniority. In Pawtucket, however, scabs feared for their lives and left town. The company rewarded the pets with a 12 1/2 cent daily raise. In November, 1902, the voters tossed out Governor Kimball for bringing in the militia and replaced him with a labor candidate, although the legislature eventually overturned the ten hour law.

A decade later in 1912 the carmen regrouped and successfully formed Division 618 to represent them. The strike of 1902, while a defeat at the time, eventually set the stage for the largest local in the state. Division 618; Amalgamated Transit Union, is still going strong today.

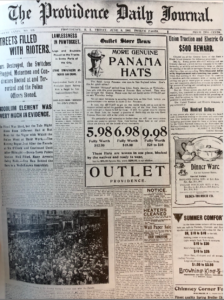

Front page of The Providence Journal, June 6, 1902. At this time, the newspaper was pro-business, conservative and opposed strikers. Some of the banner headlines include, “Streets Filled With Rioters,” “Lawlessness in Pawtucket,” and “Hoodlum Element Was Very Much in Evidence.” The following apparently merited a sub-heading: “One Man Behind Bars is a Well-Known Anarchist.”

[Banner image: Gatling gun stationed on East Avenue. The Governor sent the militia into Pawtucket, but the troops, with many strikers in their ranks, sympathized with the union.]