I am crazy about pontoons. Perhaps you could tell that from the chapter on pontoons in my recent book (with co-authors Norm Desmarais and Varoujan Karentz), Untold Stories from World War II Rhode Island (History Press, 2019). A version of the chapter on pontoons also appeared as a front-page article in the Providence Journal’s December 27, 2019 edition. The article was titled, “Pontoons made in R.I. were crucial to successful Allied invasions in World War II.”

The book’s chapter on pontoons begins as follows:

The Seabees are rightfully renowned for inventing at Davisville, and manufacturing at West Davisville, Quonset huts that were ubiquitous in all American theaters of war. The Seabees should be just as celebrated for developing and testing pontoons at Allen Harbor (also known as Allen’s Harbor) in Davisville.

Pontoons were steel boxes welded to be watertight and strung together to make structures ranging from floating dry docks, causeways, and floating self-propelled ferries. The Seabees tested newly-developed pontoon structures at the Advance Base Proving Ground in Davisville in North Kingstown from 1942 to 1945. The chapter discusses at some length an extraordinary experimental floating airfield tested on Narragansett Bay in 1943.

Of particular interest is that floating self-propelled ferries, called rhinos, were a key element of the D-Day landings on the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. Rhinos were also crucial for the first few weeks afterwards at Normandy as well, before more permanent pontoon harbor facilities could be constructed and used.

The chapter on pontoons in Untold Stories contains the following discussion of rhinos:

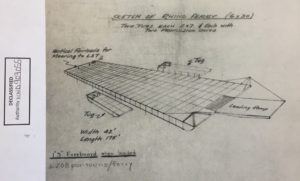

The “rhino” ferry was designed for short cross-channel operations like the D-Day invasion at Normandy. It was composed of 180 interlocked standard-size pontoons, six across and 30 long, and was powered by the largest outboard engines then available. Special curved-face pontoons were placed at the bow and stern. The ferries had steering gear, a speed of about 4 knots, a shallower draft than landing craft, and could carry a load of 275 long tons. In August 1943, Seabees conducted key tests of rhinos at the Advance Base Proving Ground at Davisville observed by senior U.S. Navy and British Admiralty officials.

Both the Americans and the British used rhino ferries for the invasion of Europe. Over 85% of all vehicular equipment landed on the American beaches at Normandy in the first 10 days came ashore on Seabee-piloted rhino ferries.

In a remarkable coincidence, my next door neighbor in Kensington, Maryland, and my friend, Philip Padgett, is a World War II historian who has focused on D-Day. He is the author of an excellent book, Advocating Overlord: The D-Day Strategy and the Atomic Bomb (Potomac Books, 2018). Philip continues to perform research about the planning leading up to Operation Overlord (what we know as D-Day) at the National Archives in Silver Spring, Maryland, where many of the United States’ World War II records are stored. Knowing of my interest in pontoons generally and rhinos in particular, when Philip came across a document detailing the testing of rhinos at Davisville, he immediately brought it my attention.

The document below summarizes the observations of a Major M. McLaurin during testing of various pontoon structures at the Advance Base Proving Grounds in Davisville in August of 1943. McLaurin was apparently a staff officer from the British Admiralty (the equivalent to the then U.S. Navy Department). Since his rank was major, McLaurin could have been a Royal Marine or even in the British Army; but his identity and connection to the British Admiralty is not known for certain at this time.

A rhino ferry carries military vehicles unloaded from an LST (landing ship, tank) in the English Channel off Slapton Beach, England, during a pre-invasion exercise. This photograph was released on D-Day, June 6, 1944. The drafts of LSTs were too deep to get close to the shores on many Normandy beaches, so rhino ferries, with a more shallow draft, were needed. (National Archives)

McLaurin mentions causeways and floating dry docks, which are discussed in my chapter on pontoons in Untold Stories. But he focuses on rhinos. They were the solution D-Day planners were seeking.

Allied D-Day planners wanted to bring ashore at Normandy as many tanks, trucks and other motorized vehicles as possible, not only on the day the invasion was to commence (D-Day), but also in the days that followed, before more permanent harbor facilities could be constructed. The tanks and trucks for the invasion of the Normandy beaches would be loaded off the coast in England on the all-important LSTs (landing ship, tank). But these large, heavy transport ships had deep draughts and therefore could not unload tanks and trucks onto beaches that had a flat slope. If the LSTs tried, the tanks and trucks would, once they drove off the LSTs, be underwater. When confronting beaches with a flat slope, LSTs needed to unload the tanks and trucks onto smaller and lighter craft with more shallow drafts. Rhinos were the answer.

Here is the text of Major McLaurin’s report on the testing of pontoons at the Advance Base Proving Ground in August 1943, almost a year before the D-Day invasion.

The joint US/British demand for pontoon equipment has been sent to B.A.D. WASHINGTON by Admiralty under three heads:

(a) Causeways for bridging the water gap.

(b) Floating docks for landing craft.

(c) Small assemblies required by the Army.

A total of 11,578 pontoons plus floating docks.

While at “QUADRANT” I flew down to the advanced base proving ground for this equipment at QUONSET, Mass. [sic, should be R.I.], on NARRAGANSET BAY to see a demonstration of a self-propelled ferry made up of pontoon equipment. I was very much impressed by what I saw, and I believe these ferries will be the solution to many of our difficulties of bridging the water gap between an LST and the shore on a flat beach slope. The prototype ferry is made up of six strings of US naval landing pontoon equipment, each 30 units long. The approximate dimensions are thus 150 feet by 42 feet. It has been called a RHINO ferry as it has a steel horn forward which fits into a hole in the ramp of an LST and locks the two together.

Draught of the ferry, of course, depends on the load. If tanks are being discharged it can be loaded to a draught of 4 feet (about 10-12 40-ton tanks). Ferry will then ground in 4 feet and tank can wade ashore. If lorries or trucks are being discharged load must be restricted to attain a draught of 2 feet 6 inches (about 40 large trucks) so that trucks can wade ashore.

The ferry is propelled by two propelling units each with one Outboard and one inboard engine and is extremely maneuverable. It has a ramp forward for vehicles to land over, and a further development may be a ramp at each end.

Ten 30 ton tanks and 2 half tracked vehicles have been off-loaded from an LST on to the ferry in 4 minutes and it is estimated that an LST could be discharged in 2 or 3 round trips depending on the load.

The ferry can be towed astern of an LST at a speed of about 8 1/2 knots; it has been tested in rough water but further trials will be necessary.

If all the trials are satisfactory the use of the RHINO ferry will obviate the necessity of beaching and laying out LSTs and may also be found very useful for discharging MT ships [large merchant transport vessels] instead of having to discharge them into LCTs [Landing Craft, Tank) or LBVs [Landing Barge, Vehicle].

It was necessary to give the Americans an indication of what our requirements would be. We learned from them that it was no good our putting in an unduly large demand. A paper was accordingly put in to P.D.(Q), Admiralty, asking for a total of 11,880 pontoons and 240 propelling units plus the floating docks already asked for by Admiralty. This number of pontoons is equivalent to 55 ferries, which we reckoned we should require. The proposal is to break about half of these down to form the small assemblies required by the Army which will be wanted when port working starts, by which time the flow of vehicles over the beaches will be diminishing.

It was made clear that this was subject to confirmation when we got home when the requirement would be sent officially through the normal channels.

The above report is the most detailed yet published on the importance of rhinos and their testing at the Advance Base Proving Ground.

A rhino ferry unloads U.S. trucks and soldiers onto a Normandy beach during the invasion of Normandy. (National Archives)

While doing further research, Phil read in a book on D-Day that the numbers of rhinos actually used on D-Day were as follows:

Western Naval Task Force (UTAH and OMAHA) — 31

Eastern Naval Task Force (SWORD, JUNO and GOLD) — 41

TOTAL Rhinos — 72

Utah and Omaha beaches were covered by the U.S.; Sword and Gold by the British; and Juno by the Canadians (part of the British forces). So the British received 41 rhinos, and not the desired 55.

Phil obtained these figures from Chris Yung, Gators of Neptune: Naval Amphibious Planning for the Normandy Invasion ( (Yung’s source was S. W. Roskill, “The Offensive,” Pt. 2 of Vol.3 of The War at Sea, 1939-1945 (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1960), no page number provided). Thanks Phil!

For those who worked on the Rhinos the night before and the day of D-Day, the conditions were miserable. Because they rode so low and did not have siding above sea level, cold, brackish water from the English Channel constantly washed onto the decks, wetting the feet of the personnel working on the Rhinos. To make matters worse, an occasional wave of frigid water would break over the crews. But it was worth the suffering to deliver the tanks and trucks onto France’s beaches.

[Banner image: Aerial view of the Advance Base Proving Ground at Davisville, September 29, 1943. Seabees experiment with different pontoon structures, including, to the right, a floating dry dock with stabilizer towers. Quonset huts are to the right. (National Archives)]