In late 1841 a large group of Rhode Island reformers led by patrician attorney Thomas Wilson Dorr bypassed the reactionary existing government by invoking the revolutionary principles of 1776. They framed and passed a new written “People’s Constitution” to replace the once liberal, but then outdated, royal charter of 1663, a modernization the other original 13 states had made long before.

The royal charter lacked a procedure for amendment, made the state seriously malapportioned, contained no bill of rights, exalted legislative power at the expense of the executive and the judiciary, and helped the General Assembly maintain a statutory real estate requirement for voting in a state that was the nation’s most urban and industrial.

The politically entrenched defenders of the charter system, especially rural Rhode Islanders, drafted their so-called Freemen’s Constitution in an attempt to head off the implementation of the People’s Constitution, a document that embraced separation of powers, contained a bill of rights and a procedure for amendment, made education a fundamental right, provided a more equitable apportionment of the legislature, and removed the existing real estate qualification for voting and office holding.

The much more conservative Freeman’s Constitution, opposed by the reformers, retained most features of the charter system but attempted to win the support of native-born Rhode Islanders by giving them the vote while still requiring naturalized citizens (most of whom were Irish Catholics) to own real estate in order to gain the franchise.

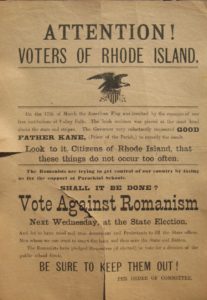

When the referendum on that proposed basic law approached in March, 1842, nativistic rhetoric became especially inflammatory. One printed broadside poster told natives that the People’s Constitution “would place your government, your civil and political institutions, your public schools, and perhaps your religious privileges, under the control of the Pope of Rome, through the medium of thousands of naturalized foreign Catholics.” This widely disseminated leaflet further advised that support of the Freeman’s Constitution was essential unless the native-born wished “to see a Catholic bishop, at the head of a posse of Catholic priests, and a band of their servile dependents, take the field to subvert your institutions under the sanction of a State Constitution.” As one suffragist complained in a letter to Dorr, “men were called upon not to vote for a constitution but to vote against Irishmen.”

The Providence Journal activated the acid pens of Henry Bowen Anthony and William Goddard on the eve of the referendum on the Freeman’s Constitution to succinctly state its case:

The balance of power rests in the hands of the Senators from the agricultural areas of the state. Where will the balance be under Messrs. Dorr, Brown and Company . . . Where but among 2,500 foreigners and the hundreds more who will be imported. They will league and band together, and usurp our native political power . . . Their priests and leaders will say to a political party as they say in New York City, give us by law every opportunity to perpetuate our spiritual despotism. At the feet of these men will you lay down your freedom . . . Foreigners still remain foreign and are still embraced by mother church. He still bows down to her rituals, worships the host, and obeys and craves absolution from the priest. He cannot be assimilated . . . Now is the time to choose between the two systems, the conservative checks or foreigners responsible only to priests.

Although the Freeman’s Constitution was narrowly rejected, the charter government, operating as the Law and Order Party, called out the militia to prevent the implementation of a new government under the People’s Constitution and forced Thomas Dorr, then the People’s Governor, into exile.

Late in 1842, the Law and Order coalition called another constitutional convention. With the reformers defeated, Dorr’s departure, and the invocation of martial law by the victors, this Law and Order Constitution was ratified by a greatly reduced electorate in November 1842 and became the basic law of Rhode Island in May 1843. It was the antithesis of the People’s Constitution. Among its many reactionary features were a difficult amendment procedure, the lack of a provision for the call of future constitutional conventions, a rural dominated senate with each municipality given one vote regardless of population, and, especially, the retention for naturalized citizens of the real restate requirement for voting and holding office. The existence of this provision made Rhode Island’s basic law the most nativistic in America.

William Goddard was born in Johnston in 1794. After receiving his undergraduate and master’s degrees from Brown University, he became a professor at the school. A prolific writer his works were often published in pamphlet form or in the pages of the Providence Daily Journal. A decided conservative and “Law and Order” man he wrote a series of articles in the Journal defending the position of the Charter government.

In one pamphlet focusing on the Dorr Rebellion, Goddard wrote:

In the late revolutionary movement which convulse this State, were engaged men who, under the laws of the State, had no right to the exercise of political power. They endeavored to compel the body politic to receive them as members. Among these men were persons born in this State, and persons who came hither from abroad. What rights had the latter, beyond those which belonged to an invader?

By persons not born in Rhode Island, presumably Goddard was referring primarily to Irish Catholic immigrants. Goddard died in 1846, before the rise of the Know-Nothing party in the 1850s, which promoted ugly anti-Catholicism and nativism.

Henry Bowen Anthony was born in Coventry, Rhode Island in 1815 and graduated from Brown University in 1833. At the very early age of twenty he became associate editor and publisher of the Providence Daily Journal. He would stay associated with this newspaper for the remainder of his life. This Whig newspaper was decidedly conservative in its views and that suited Anthony’s well. As one of the leading newspapers in Rhode Island during the time of the Dorr Rebellion he used his position and pen to fend off any ideas of suffrage reform. As a skilled writer he used the pages of his newspaper to shape the thinking of its readers. In a sense his editorials were the voice of the conservative, Law & Order, party, that rejected the notion of reform measures in suffrage qualification for Rhode Island voters.

The Journal spewed forth many anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiments. These nasty diatribes after the rebellion carried over to the controversial trial of John and Nicholas Gordon, two Irish immigrant brothers accused of the murder of wealthy manufacturer Amasa Sprague.

Election poster urging “True American and Protestant” Rhode Island voters to “Vote Against Romanism” (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

In 1848 Anthony was elected governor of Rhode Island, a position he held for two consecutive terms. In 1851 the Journal printed a decidedly anti-Catholic screed under the title of “Citizenship Made Easy,” in which it remarked on Catholics being adding to the voting lists in other cities. The editorial added,

Here is an example of two hundred persons added to the voting list because the Pope had commanded it, and they were required for the election of the Catholic candidate. . . . The federal laws furnish no protection against these frauds; but the states can protect their own suffrage from this foreign invasion.

When Irish Catholics campaigned for the removal of this restriction in the aftermath of the Dorr Rebellion, the Journal’s Henry Anthony declared his unyielding opposition to such a change, even for naturalized Irish-Catholic soldiers who had fought in the Civil War to preserve the Union.

Anthony represented Rhode Island in the United States Senate from 1858 until his death in 1884, including as President Pro-Tempore from 1869 to 1873 and again in 1875.

The bigoted Anthony, as an influential United States senator, also used his influence to limit the scope of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Black vote only, thereby preserving Rhode Island’s discriminatory suffrage system. In the words of Anthony’s Providence Daily Journal, if that restriction is removed “Rhode Island will no longer be Rhode Island when this is done. It will become a province of Ireland: St. Patrick will take the place of Roger Williams, and the shamrock will supersede the anchor and Hope.”

During his time in the Senate, in 1881, Anthony was forced into the unenviable position to defend the state ’s antiquated suffrage requirements in a speech titled “Defense of Rhode Island – Her Institutions and Her Right to Her Representatives in Congress.”

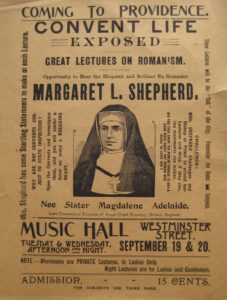

Advertisement for the lecture at Providence by a former nun, titled “Convent Life Exposed” (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

In 1884 U.S. Senator Anthony took his nativisitic positions to his grave. In 1888, the retention for naturalized citizens of the real restate requirement for voting and holding office was removed from the state constitution by Article of Amendment VII, but this change was made primarily for partisan political purposes rather than for the principle of equal rights.