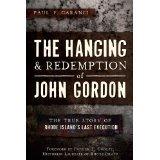

If you love true crime stories, or tales of political and judicial corruption, or if you are just a fan of history, you will love my book, The Hanging & Redemption of John Gordon, The True Story of Rhode Island’s Last Execution. A Providence Journal book review called it one of the top 5 non-fiction books of 2013. It is truly a story with many lessons for today as it chronicles the impact of prejudice, hatred and bigotry, not only on a single family, but on society itself.

Here’s how it went down.

On a frigid day in 1843, Amasa Sprague, a wealthy Yankee mill owner, left his mansion in Cranston to check on his cattle. On the way, he was accosted and beaten beyond recognition, and his lifeless body was left face down in the snow. What followed was a trial marked by judicial bias, witness perjury and societal bigotry that resulted in the conviction of twenty-nine-year-old Irish Catholic John Gordon. He was sentenced to hang. Despite overwhelming evidence that the trial was flawed and newly discovered evidence that clearly exonerated him, an anti-Irish Catholic establishment refused to grant him a new trial. On February 14, 1845, John Gordon became the last victim of capital punishment in Rhode Island.

The Hanging & Redemption of John Gordon brings the case to life, graphically describing the murder, and exposing a corrupt judicial system, a biased newspaper and a bigoted society responsible for the unjust death of an innocent man.

But this case would not end with the death of John Gordon. Over 150 years after his conviction and execution, John Gordon was exonerated in what would become just one more incredible twist in the story of John Gordon. No one else was ever charged with the crime, making the murder of Amasa Sprague one of Rhode Island’s oldest cold cases.

A Synopsis

The Sprague family arrived in America in 1628 and by the early 1800s, they pretty much controlled everything in their sphere of influence in Rhode Island. With former Governor William Sprague serving as a U.S. Senator, and other family members holding seats on the Cranston town council and in the state legislature, the Spragues were in charge of the local political structure. As the owners of several mills, including the A & W Sprague Mill in Cranston, they controlled the local economy. And as owners of several mill villages that included many duplex-style homes that housed the mill workers, a place of worship, and a mill store with inflated prices, they controlled all things social. Because the mill owners paid their employees with script that could be used only for the payment of rent and the purchase of goods from the mill store, their employees, primarily Irish Catholics, were held hostage to the mill and its owners. Most of their monthly salary would be spent at the store for food and supplies, and on rent, long before pay day arrived ensuring that the employees were forever in debt to the mill owners.

Nicholas Gordon came to America in 1836 to escape the coming famine and other social and economic hardships of life in Ireland, then a colony of England. He was also able to escape the burden of life as a mill worker once he arrived in this country. Rather than apply for work in the mill, as many of his countrymen had, he opened a store in rented quarters in Knightsville until he was able to afford to purchase a piece of land on which he built a store with a second floor apartment in Spragueville, just a few yards up the road from the Sprague Mill. Around the same time, he purchased a handgun and a rifle for hunting purposes, and as a means of protection against intruders at his home and store.

In 1840 Nicholas Gordon applied for and received a license to sell alcohol by the bottle in his store and his business was brisk. He knew, however, that selling alcohol by the glass would be much more lucrative. To that end, he applied for, and received, a tavern license. His business was so good that he was able to pay for passage of his entire family to join him in here in America. His mother Ellen, his sister Margaret, his brothers John, Robert and William, and William’s seven-year-old daughter Margaret arrived on June 19, 1843, in what had to be a most joyous reunion. His mother burst with pride at what her oldest son had accomplished and the others could barely control their excitement at being able to start a new life in the land of abundance and opportunity. The sweet smell of Nicholas’s success, however, would soon begin to sour.

Amasa Sprague, meanwhile, grew tired of his Irish employees drinking before and during working hours. They were arriving to work late, or worse, drunk. Productivity in the mill was slipping and work related accidents were increasing, and Sprague blamed Gordon!

Amasa Sprague made a move to take away Gordon’s liquor license and because he was a former town councilman, he was able to achieve his goal without much fanfare in July 1843. Gordon, however, was confused. He hadn’t been selling alcohol to the mill workers and believed that another store owner, Job Wilbur, who didn’t even have a license to sell alcohol, was providing the drinks to the mill workers illegally. It didn’t matter. In just minutes, Gordon, who had just taken on the full financial responsibility of his entire family, lost a significant amount of his income. He was upset and some witnesses said that they heard him threaten Amasa Sprague.

An old photograph of the Nicholas Gordon home, which has since been torn down (Paul Caranci Collection)

Just a few months later, on December 31, 1843, Amasa Sprague left his mansion to check on the furnace at his mill and then on his livestock on a farm near the Johnston-Cranston town line. Before he could do so, however, he was attacked and brutally murdered just after crossing the string bridge over the Pocasset River that connected the two towns. Shot and beaten beyond recognition, his body was discovered a few hours later by one of Sprague’s employees who was on his way home from work at the mansion. Despite having worked for Sprague for a number of years, he didn’t even recognize that the victim was his boss.

Immediately, speculation grew that Nicholas Gordon had killed Amasa Sprague. The Providence Journal ran adverse stories against the Gordon family and Nicholas was arrested the next day, even before a single shred of evidence had been found. The day following Nicholas’s arrest, John, William, Robert and Ellen were arrested along with their close family friend, Michael O’Brien. Even the family dog was taken into custody so as to try to match its paw prints with paw prints found in the snow at the scene of the crime.

A bungled investigation resulted in the indictment of Nicholas, John and William. A corrupt trial produced the desired result. John Gordon was found guilty and sentenced to hang on Valentine’s Day 1845 in the yard of the State Prison, which was located on the very spot of the Providence Place Mall.

Despite the discovery of new evidence that might exonerate John, a new trial was denied. The state legislature even refused to postpone his execution until after the second trial of Nicholas could be held, despite the prospect that at this trial perjured witnesses could be exposed and exculpatory evidence could be presented.

In the end, twenty-nine-year-old John Gordon was blind folded with a handkerchief supplied by his mother and executed following a very emotional final statement.

The corrupt nature of the investigation and trial exposed society’s bigotry and hatred. That exposure resulted in the state’s abolition of the death penalty in 1852, just seven years later. The action made Rhode Island the first state in the country to abolish capital punishment for all crimes.

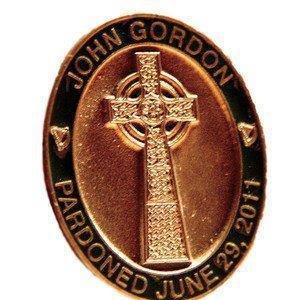

And then, on June 29, 2011, in the ceremony held in the same room in which John Gordon was found guilty, the last man executed in the state was pardoned. Governor Lincoln Chafee signed a bill of pardon that was initiated in the Rhode island General Assembly by Representative Peter F. Martin and Senator Michael J. McCaffrey several months earlier.

Despite an entire family being destroyed personally and economically, and an entire ethnic group losing faith in a judicial system intended to provide justice, the Gordon family name was finally cleared.

The Investigation

In 1844, forensic science was unheard of, and blood typing and DNA testing were still years away from becoming a reality. Investigators, therefore, were forced to rely on common sense investigatory skills to solve crimes. It seems that even those skills were absent from the Sprague murder investigation. What was so wrong? Here’s a partial list of questionable police methods:

- Based on a biased newspaper article that appeared in the anti-Irish Catholic Providence Journal, tens of untrained, unskilled volunteers flooded the crime scene in search of clues that might convict the Gordon family.

- Only footprints in the snow that led from the scene of the murder to the Gordon home were measured and tracked. All others were trampled, altered or ignored.

- The family dog was arrested in a foolhardy attempt to match the dog’s paw prints with paw prints found in the snow at the spot of the murder.

- The brother of the victim resigned his seat in the U.S. Senate to lead the investigation, usurping the authority of the sheriff.

- Evidence was taken to the Sprague mansion for safe keeping rather than to the Sheriff’s Office, thereby destroying any semblance of an appropriate chain of custody.

- A “blood-stained” coat found near the scene of the murder was so big that it wrapped around the body of John Gordon. Yet, it was alleged in court to have belonged to Gordon as a witness said that she saw him wearing it in the past.

- A gun belonging to Nicholas Gordon was alleged to be the murder weapon simply because investigators did not find Nicholas’s gun, which at the time of the first search of his store, was in plain view behind the counter.

- There were many other “abnormalities” associated with the investigation of Amasa Sprague’s murder, most of which point to a preconceived conclusion driving the investigation rather than an impartial investigation arriving at a justifiable conclusion.

The Trial

The trial was also fraught with prejudice and anti-Irish Catholic bias. Here are just a few examples:

- A decision was made to try William and John Gordon together meaning that evidence presented against one brother could be used against the other.

- The gun, found in pieces at the murder scene, was assumed to belong to Nicholas Gordon simply because investigators failed to find Nicholas Gordon’s gun when they searched his store. The judge allowed this evidence to stand and was the basis for John’s conviction.

- It was assumed that Nicholas’s gun was in the hands of John Gordon on the day of the murder despite no credible evidence to support that fact.

- A prostitute testified that she was much more than a casual acquaintance of John and William Gordon having shopped in Nicholas’s store several times a week for several months. When asked by defense counsel to identify them, she misidentified John as William and William as John.

- The testimony of many witnesses for the prosecution contradicted the testimony of other prosecution witnesses, while tens of defense witnesses offered consistent testimony which included an alibi for the Gordon brothers who, that day, were attending a Christening miles away from the murder scene. Despite that, the Judge instructed the jury to put more weight on the testimony of the Yankee witnesses and less on the testimony of the Irish witnesses.

Post-Trial Injustice

William Gordon had been keeping a terrible secret, one that he was convinced to reveal just a few weeks before the execution of his brother. He had hidden the two guns belonging to Nicholas. Further, he led authorities to the place where he had hidden the guns and they were recovered intact. This meant that the gun found in pieces after being used to crush the skull of Amasa Sprague, did not belong to Nicholas Gordon.

An old photograph of the String Bridge over the Pocassett River connecting Johnston to Cranston. Cranston is on the right side of the bridge. The murder of Amasa Sprague took place just over the bridge into Johnston (the left side of the bridge.) (Paul Caranci Collection)

Despite this new evidence being uncovered proving that the gun belonging to Nicholas was not the murder weapon, a key piece of evidence on which John was convicted, John was denied a new trial at which the new exculpatory evidence could be presented. In addition, the General Assembly refused to postpone the execution of John until after the 2nd trial of Nicholas (the first trial ended in a hung jury) during which the new exculpatory evidence could be presented. At that second trial, which also ended with a hung jury, the defense provided evidence that witnesses had perjured themselves during the initial trials.

Who Really Killed Amasa Sprague?

The answer is, we don’t know. We may never know. In their misguided attempt to convict an Irish Catholic for the crime, no one ever investigated any of the people who may have had motive and opportunity. I did not speculate in The Hanging & Redemption of John Gordon because, with the passage of almost two hundred years, and the destruction of any evidence that was collected at the time, there is no way to prove who committed the crime. But here is a list of people who probably should have been questioned with regard to Amasa’s murder:

- Big Peter Dolan: Peter worked in the Sprague mill and was no fan of Amasa. In fact just a few days before the murder, Sprague fired him for destroying the loom where his nephew’s fingers were torn off. Dolan had been described as an angry man, and he was big. The “blood-stained” coat found at the scene of the murder, while wrapping around John Gordon, would have fit Big Pete nicely. Peter Dolan disappeared the day after the murder and was not seen by anyone in Rhode Island again. There is speculation that he moved to Pennsylvania where he, while on his death bed, confessed to his priest that he committed the crime.

- Mrs. Fenner and her husband: It was widely speculated at the time that Amasa Sprague was having an affair with Mrs. Fenner, who owned a boarding house in Johnston, just on the other side of the String Bridge where the murder took place. Was Amasa Sprague murdered by Fenner’s husband who may have learned of the illicit relationship?

- Fanny Sprague: Could the murder have been arranged by Fanny Sprague, Amasa’s aggrieved wife, after she learned of the affair?

- William Barker and Bowen Spencer: These two friends testified that they were near the scene of the crime and saw John and William Gordon both before and after the murder. However, because other witnesses were talking with William Gordon miles from the murder scene at the same time, their testimony was clearly falsified. No one ever bothered to question these two men who placed themselves in the vicinity of the murder at the time the crime was committed.

- William Sprague: Charles and Tess Hoffman, in their book, Brotherly Love: Murder and the Politics of Prejudice in Nineteenth-Century Rhode Island, argue that Amasa was murdered by his own brother. William and Amasa disagreed on the expansion of their mill empire. Amasa believed that expansion would be a mistake if the economy faltered. William disagreed and the two fought openly about the issue. Just days after Amasa’s murder, William resigned his seat in the U.S. Senate to lead the investigation into his brother’s murder. What better way to ensure that speculation never led in his direction? Ironically, once in control of the mill empire, William did expand beyond what a declining economy could handle and he was forced into bankruptcy several years later.

There is no way to know today if any of these people were involved with Amasa Sprague’s demise over 170 years ago, but it would have been interesting if some of them had been investigated at the time of the murder when the memories of those who would have testified were fresh and tangible evidence still existed.