“I could easily have been an acrobat”: thus wrote the famous American feminist author in her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman.[1] The author, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, was recalling the time in the 1880s when she regularly attended a Providence ladies’ gymnasium. She was so enthusiastic that she was only half joking when she wrote to a friend in 1882: “I the strong and impregnable: I, the budding athlete, and Chief Performer at the Providence Ladies’ Sanitary Gymnasium; I, the sure-footed and steady-eyed, ignominiously tumbled over a chair, and so injured myself that I was laid up for four days.”[2] But she was back at the gym within a week.

Charlotte Anna Perkins Gilman (1860-1935) spent from 1873 to 1888 in Providence, at the time one of the wealthiest and fastest growing cities in the United States. During her adolescence and young womanhood, the city’s population almost doubled from around 69,000 in 1870 to over 132,000 in 1890. Major and growing companies such as Brown and Sharpe, Corliss Steam Engine, Gorham Manufacturing, Fruit of the Loom and Nicholson File hired tens of thousands of immigrants.

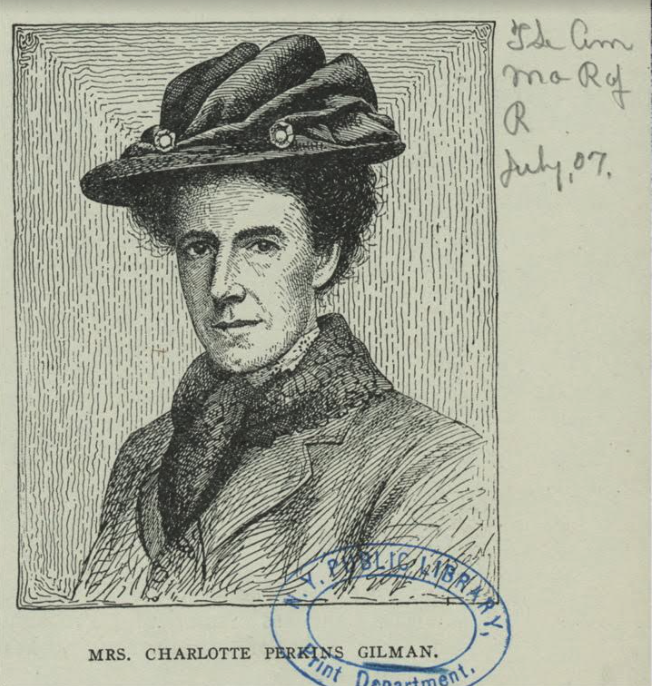

Charlotte Perkins Gilman in 1907, when she was around 47 years old (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Institutions emerged to cope with the increasing industrialization of life in Providence. Roger Williams Park and Zoo opened in 1872, giving a breath of fresh air to tenement dwellers. In 1877 the Rhode Island School of Design began, its first courses in Freehand Drawing and Mechanical Drawing and Design to train people for the textile and jewelry industries.[3] The Providence Public Library opened its doors (in 1878), as did the Roman Catholic cathedral dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul, to cater for the many immigrants from Southern Europe. Leisure was provided for by the Providence Grays baseball team, which was founded in 1878 and won the World Series in 1884. By the 1870s one or two gymnasia had also opened.

Charlotte explored what it was like to be a woman during a time of rapid social and economic change.[4] She seems to have been conflicted between nonconformity and conventionality. It was not an easy time to be a financially straitened white, middle class woman, as roles beyond wife and mother were slow to develop and Charlotte grew up at a time when there was a virtual epidemic of ill-health among similarly conflicted American women. Being a member of her family was not easy, either. Although she was related to the celebrated Beecher family—Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe were her great aunts— her father effectively abandoned his wife and children. She was raised by her unhappy mother who had next to no money and relied on relatives for support. Charlotte would have known the arguments about women’s education, suffrage, and motherhood, and that some women suffered a range of symptoms including headaches, weakness, depression, indigestion, and menstrual difficulties.[5]

Charlotte coped by taking vigorous exercise. One exercise proponent quipped in 1879 that “General debility is heard of nowadays almost as often as General Grant,” while proposing that a program of exercise, at home or in a gym, might “keep nervous disorders at bay” and give women “the bloom and healthy look.” This expert was New York lawyer and athlete William Blaikie (1843-1904). Charlotte purchased his 1879 book on How to Get Strong as soon as it was published. She followed his instructions carefully, and started stretching and weight training. She recorded in her diary, “Follow Blaikie every night with the greatest assiduity. I can put all my fingers on the floor, knees straight to count of 30.”[6]

Charlotte may have been young, fit and supple, but she had a patchy education. She briefly (and irregularly) attended Miss Shaw’s Young Ladies’ School on Westminster Street, but left at the age of fifteen.[7] When she studied at the newly opened Rhode Island School of Design she continued informal exercise, walking “briskly” the mile or so from her home on Manning Street to the school’s premises, which were on the top floor of a building on Westminster Street. She “disdained” the elevator and, she wrote, “in a month or so I was running up the whole four flights two steps at a time, beating the elevator, to my immense satisfaction.”[8]

Charlotte supplemented her education by becoming a member of the Society for Encouraging Studies at Home, set up in Boston by Anna Eliot Ticknor. She also researched for her essays at the Providence Athenaeum, dashing in and out several times a week.[9] In the winter of 1881-82 she was in the library almost every day studying the history of Egypt. One day she took some crackers for her lunch “and read Egypt in the Ath.” She met her friends there and used it as a stopping-off point between (her many) activities. In the fall of 1881, for example, she attended the Ladies’ Gymnasium in the afternoons and taught a Bible class in the evenings and stopped by at the Athenaeum between the two, writing simply “Gym. All serene. Athenaeum. Good read. Call for Miss Russel and we go to the Bible Class. Home alone.” She and the handsome young artist Walter Stetson, the man she eventually would marry, did some of their courting there, which may explain why she reported “a little fuss” with Miss Angell, the librarian.[10] After almost two years of indecision, Charlotte married Stetson in 1884.

Charlotte, regretfully, decided that exercise was inappropriate for married women. This seems to have been her effort to become the sort of wife she thought she should be. Walter, on the other hand, appreciated her athleticism, writing after their first meeting “She has a form like a young Greek & a face resembling a cameo. She is an athlete—strong, vivacious, with plenty of bounding blood.”[11]

Before she decided to become the perfect housewife, which was momentously bad for her mental health, Charlotte had enjoyed exercising several times a week at a ladies gym run by Dr. J. P. Brooks. She first met him in 1875 when he taught at her school. His class was one of the few she enjoyed. Charlotte later recalled, “Calisthenics, taught by an upright young Dr. Brooks, strongly appealed to me. I became so upright that I fairly leaned backwards and marched with such conscientious precision that he called me out as an object lesson, to march around with him.” Brooks was already running a gymnasium offering “Movement Cure and Health Lift” at his premises at 37 South Main Street in 1871.[12]

Charlotte approached Brooks in 1881 and asked him to set up a woman’s gym. She may have heard about the one Mary Allen had recently opened in Boston. She told him she wanted “a class in the higher gymnastics for young ladies, just a few of us, a nice set, and a hall with facilities where we could wear abbreviated garments and elevate the massive dumbbell at our leisure.” At first Brooks was dubious. “He said not enough women wanted it,” she recalled. Charlotte asked him how many he would need. Brooks responded, “about thirty.” That was good enough for Charlotte. She energetically “set forth, visited every girl I knew and many I didn’t, and got up a class, not thirty indeed, but enough to encourage him to begin.”[13]

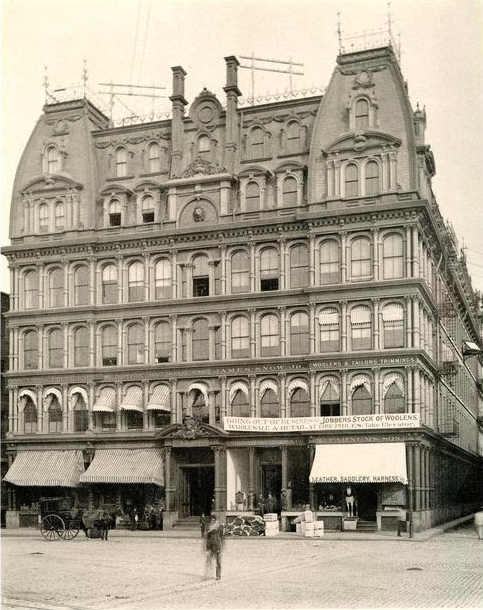

Brooks was persuaded to move forward with Charlotte’s plan. He rented space on the fifth floor of the brand-new Butler Exchange Building, located on what is now Exchange Place. (It burned down in 1925 and was replaced by The Industrial National Bank Building, now famous as the Superman Building, at what is now 111 Westminster Street or 55 Kennedy Plaza.) Brooks consulted D. A. Sargent, a former circus performer turned medical doctor who, as a Professor of Physical Training at Harvard University, had headed Harvard’s new Hemenway Gym since 1879. Brooks selected exercise equipment on Sargent’s advice. Brooks then asked Charlotte to design a stencil border for the wall—and gave her a free membership.

The Sanitary Gymnasium for Ladies and Children that Charlotte Gilman Perkins had a role in creating was located in the Butler Exchange Building at what is now 111 Westminster Street or 55 Kennedy Plaza (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Brooks named the new exercise facility the “Sanitary Gymnasium for Ladies and Children.” His advertisements promised to “Broaden Narrow Chests and Strengthen Weak Muscles” and provide the “Movement Cure for the Treatment of Extreme Nervous Prostration When All Other Means Fail.” It opened in late 1881, offering to “promote a healthful use of gymnastic exercise among ladies and children. . . . The exercise for each individual is carefully prescribed, and over-exertion prevented.”[14] By 1884 (the year Charlotte married and stopped going to the gym) it was described in the Providence Directory as the “Finest Location and Best Equipped Gymnasium in the United States.”

Brooks was particularly interested in a new-fangled health lift machine, and indeed wrote a little pamphlet about it. Illustrations of health lift machines show the patient standing on a large platform which resembled a car jack. Brooks described it as “a large iron machine, so arranged with springs and artificial cartilages of rubber that as the weight is taken upon the body all shock or jar is prevented.” Pasted in his own copy of Brooks’ book is a picture of Mann’s Reactionary Health-lift. The woman is wearing a bonnet, a corset and a bustle while exercising![15]

An advertisement for a health lift exercise machine in New York City. Brook’s gym in the Butler Exchange Building had one too. To use it, the individual stood on the platform and lifted up.

Charlotte’s friends were indeed a “nice set.” Her fellow exercise enthusiasts included members of many of Rhode Island’s established families. She mentioned some of them in her diary, writing on November 4, 1882, “Gym. Lots of folks in, Miss Almira Rathbone among ‘em.” And on January 27,1883: “Gym. Polka race with Connie Pitman. Nice time.” On March 31, 1883: “Call for Connie Pitman to go down with her. Run 50 laps and do lots of other work. Grace Channing came in—partly to see me perform.” One of Charlotte’s friends, and a fellow member, was Caroline Hazard. When she became president of Wellesley College, she set up a graduate department of hygiene and physical education. Caroline Hazard’s father was a wealthy textile manufacturer in Peace Dale; the Rathbones had been in Rhode Island since the seventeenth century; Connie Pitman’s father was for forty years clerk to the United States Circuit Court; Grace Channing’s grandfather was William Ellery Channing, founder of the Unitarian church, while her father was an inventor who worked with Alexander Graham Bell on the invention of the telephone. Grace was a kindergarten teacher in 1883, perhaps why she was watching rather than running and jumping. (She and Charlotte later became close friends in Southern California, and Grace even married Walter Stetson after his divorce from Charlotte—and even helped raise Charlotte’s daughter.[16]

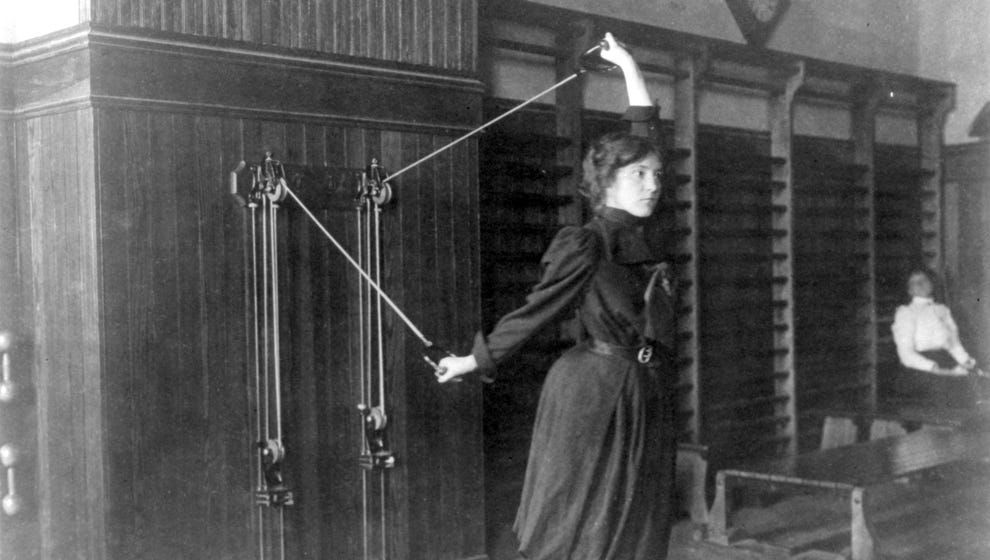

Charlotte visited the gym at least three times a week, and in the weeks preceding her marriage she went almost every day. In addition to calisthenics (defined as repeated, often rhythmic exercises to strengthen the large muscles) with dumbbells or Indian clubs, she used fixed apparatus on which she vaulted, jumped, and climbed. Her favorite activity was the traveling rings. They were stirrup-shaped and suspended from the twenty-five-foot ceiling. She would mount a table with a ring in her hand, draw it back, then “launch forth in a long swing and catch the next [ring] with the other [hand] …and go on swinging…down the five and back again.” She added “that is as near to flying as one gets, outside of a circus. I could do it four times in those days.”[17]

Charlotte was so enthusiastic about the gym that she wrote an article about it for the Providence Journal on May 23, 1883. In this, her first published nonfiction, she claimed that there were 71 regular workers among the ladies, and hoped that next year there would be more, who would “testify to the good sense and energy of Providence womankind; let them show their appreciation of the fact that (this is stated on competent authority) although there are larger, there is no institution on earth that rivals in beauty and completeness of outfit the Providence Ladies Gymnasium.”

High school girls work out with dumbbells in a gym class in Washington, D.C. in 1899 (Library of Congress)

After Charlotte Gilman and Charles Stetson married in 1884, the couple had a daughter, Katherine (1885-1979). Charlotte, who had given up her visits to the gym, suffered from severe postpartum depression. After a failed “rest cure” with celebrity doctor Silas Weir Mitchell she moved to Southern California in 1888, moving almost as far away as she could get from her unhappy marriage. The Yellow Wallpaper is a semi-autobiographical novella she published about her experiences with the rest cure.[18] She resumed regular exercise, interspersed, however, with bouts of depression, writing that nearly two-thirds of her adult life were spent “as if trying to rise and walk under a prostrate circus tent, or wade in glue.”[19]

In California Charlotte developed a national reputation as an author, speaker and champion of women’s rights and other social causes. She received her divorce from Stetson in 1894, and married her first cousin, Wall Street attorney George Houghton Gilman, in 1900. She wrote several important books including Women and Economics (1898) and the feminist novel Herland (1915). The couple lived in New York until 1922, and then in Norwich, Connecticut, until George’s sudden death in 1934. Charlotte moved to Pasadena, California, where her daughter lived, and in pain from terminal breast cancer took her own life in 1935.

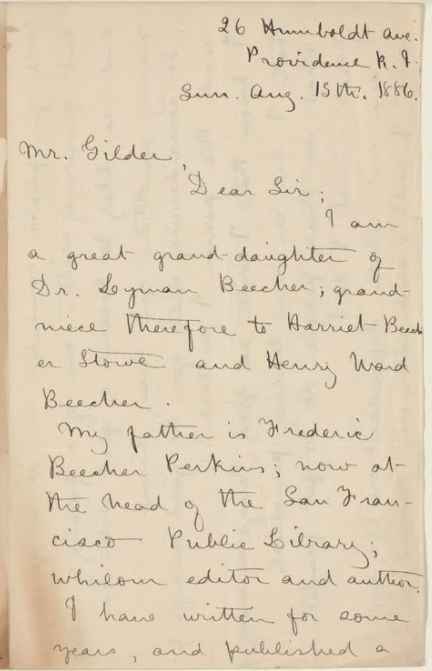

Cover page to a letter written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman from Providence in 1886. She was trying to get some of her poetry published. To that end, she started the letter, “I am a great-granddaughter of Dr. Seymour Beecher, grand-niece, therefore to Harriett Beecher Stow and Henry Ward Beecher.” Charlotte later became a successful and prolific author (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Notes

[1] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography, Introduction by Ann J. Lane (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 64. [2] Quoted in Jane Lancaster, “‘I could easily have been an acrobat’: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Providence Ladies Sanitary Gymnasium, 1881-1884,” ATQ New Series 8:1 (March 1994), 33. All quotations from the diary were taken from the Charlotte Perkins Gilman papers in the Schlesinger Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts, which are now online at https://schlesinger.radcliffe.harvard.edu/onlinecollections/gilman/item/13662551/1.Charlotte’s diaries were published in, Denise D. Knight, ed., The Diaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1994), and selections from her letters were published in Mary Hill, ed., A Journey from Within: The Love Letters of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Lewisville, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1995), and Denise D. Knight and Jennifer S. Tuttle, eds., The Selected Letters of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2009).

[3] See online history of the Rhode Island School of Design at https://www.risd.edu/about/history-and-tradition. [4] There have been several biographies of Gilman. See Mary A. Hill, Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Making of a Radical Feminist 1860-1896 (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1980); Ann J. Lane, To Herland and Beyond: The Life and Work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (New York: Meridian Books, 1991); Cynthia Davis, Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010). [5] See Barbara Ehrenreich and Deidre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Expert’s Advice to Women (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1978) and Patricia Vertinsky, The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1990). [6] William Blaikie, How to Get Strong and How to Stay So (New York: 1879), 57 and 63. The book has been digitized by Project Gutenberg at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/36557/36557-h/36557-h.htm#page218. [7] See the online https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:311513/ for a leaflet about Miss Shaw’s school. [8] Gilman, Living, 46 and 64. [9] Bergmann, Harriet F., ““The Silent University”: The Society to Encourage Studies at Home, 1873-1897,” The New England Quarterly 74, no. 3 (2001), 447-77. Accessed online May 20, 2021, doi:10.2307/3185427. [10] Gilman diary, quoted in Jane Lancaster, Inquire Within: A Social History of the Providence Athenaeum Since 1753 (Providence: Providence Athenaeum, 2003), 111 (the crackers, November 10, 1881; the little fuss, May 11, 1882). [11] Mary A. Hill, ed., Endure: The Diaries of Charles Walter Stetson (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1985), 25. [12] Gilman, Living, 28. [13] See online article https://www.universalhub.com/2016/womens-exercise-movement-19th-century-boston; Gilman, Living, 66. [14] “Ladies’ Sanatory Gymnasium,” in Moses King, King’s Pocket-book of Providence, R.I. (Providence, RI: Tibbitts, Shaw & Co., 1882). [15] J.P. Brooks, Exercise Cure: The Butler Health Lift, What It Is and What It Will Do (copy found in The John Hay Library, Brown University. See also the online article, ttps://physicalculturestudy.com/2015/11/10/the-health-lift-the-greatest-machine-youve-never-heard-of/ [16] See the article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Ellery_Channing. There does not seem to be a biography of Grace Channing Stetson, who led an interesting life as a prolific author, based mostly in Rome where Walter went to paint, and after Walter’s death, as a war correspondent. She died in New York in 1937 after years of poverty and ill health. [17] Gilman, Living, 67. [18] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper is available as an e-book from Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1952/1952-h/1952-h.htm. See also Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Wild Unrest: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Making of The Yellow Wallpaper (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). [19] Gilman, Living, 102.