At the beginning of World War II there was an urgent need for ships. Lots of them, of all types and sizes were required, and in a hurry. Warships for the navies, transports for the armies, freighters and tankers for the merchant marine, and innumerable small craft and auxiliary vessels were needed. Warfare that spanned most of the world’s oceans could not be conducted successfully without massive resources of transport by sea—and protection of such transports.

Current and recent generations may find it difficult to accept the reality of that statement, but it must be understood that in the late 1930s the movement of people and goods throughout the world was dependent on vastly different means than today. Transportation on land was mainly by railroads. There were no interstate highways for rapid movement of large capacity trucks, and such vehicles had not even been imagined. Air transport was developing, but long-distance flights were limited to seaplanes and airships, and the general public considered those options adventurous, expensive, and downright dangerous. The movement of people and tangible “things” between continents was entirely by sea. Any study of World War II history must be viewed from that perspective.

Great Britain was the first of the Allies to expand its shipbuilding industry. In addition to ramping up warship construction, it was obvious that a huge merchant marine was needed. As an island nation, dependent on supply from beyond its shores, Britain was vulnerable to any threat to replenishment by sea. That threat had been experienced during World War I, but now the danger was even greater. Following the recovery of Germany after World War I, Germany had developed formidable air force assets and a navy especially focused on attack submarines. Once World War II commenced, it was clear that soon there would be interruption in supply lines for the military, and also for the feeding and survival of the entire civilian population. Britain’s tradition of ruling the seas was in jeopardy. Commonwealth nations were quick to respond, with Canada in the best geographical position to help.

The United States was neutral, with a strong anti-war movement in the 1930s. But its future involvement in war with Germany or Japan was a realistic possibility and arguably inevitable. As a result, and with the prodding of the U.S. Navy Department, United States ship designers and builders began to prepare.

International treaties between the major world powers had placed severe limits on the number and types of warships that could be maintained after World War I. When the United States was attacked on December 7, 1941, all those restrictions became moot. Shipbuilding was given the highest priority, and the U.S. navy yards at Boston, New York, Portsmouth, and elsewhere went into maximum activity. Also, the long-established civilian shipyards, such as those at Bath Maine, Groton Connecticut, and Newport News, Virginia, responded in kind. However, it was recognized that those facilities would not be able to produce the numbers of vessels needed.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, well understood the situation, and he injected himself into the issue using his executive authority. Orders were issued to establish eighteen emergency shipyards throughout the country. Selection of location was determined by assessing a candidate site for its easy access to the sea, and the potential availability of a large local labor force. One of the places meeting those criteria was Providence, Rhode Island. It was declared a winner by the United States Maritime Commission.

The Providence emergency shipyard was created at Field’s Point during 1942. At the extreme south end of the city, the waterfront there is at the head of Narragansett Bay, directly aligned to the Atlantic Ocean, just beyond Newport a few miles away. The Field’s Point neighborhood was adjacent to Allen’s Avenue, convenient for workers commuting by car or bus. A further advantage was its close proximity to major rail lines. It would be easy to lay short spur track connections to bring in every type of material and equipment required for building ships. It was an ideal location for a shipyard.

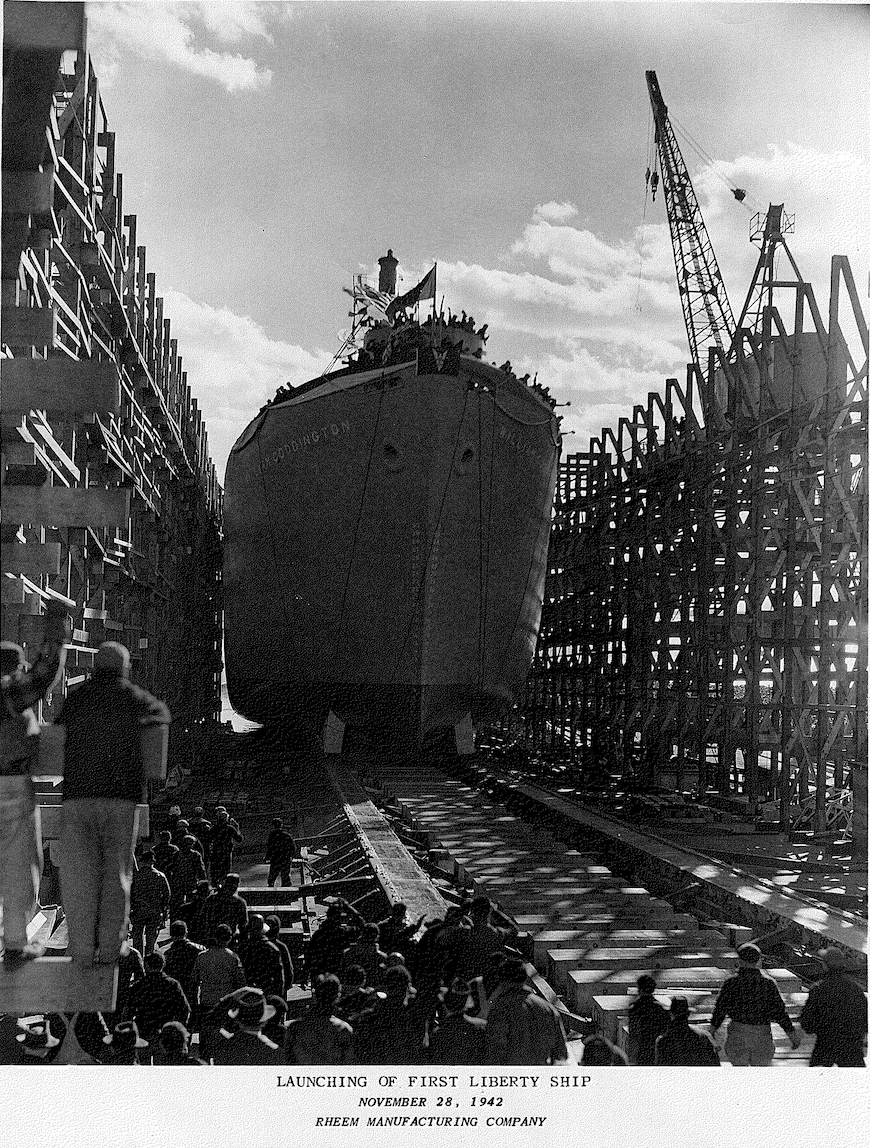

The emergency shipyard operational concept was simple. The Maritime Commission was the owner of the yard and its products [ships], but local management and operations were the responsibility of a civilian contractor. The Providence yard was initially assigned to the Rheem Corporation, a mid-western company that manufactured a variety of military items (including steel shipping containers and practice bombs for aircraft), but which had absolutely no experience in shipbuilding. As a starter project, Rheem was ordered to build a fairly simple freighter, one of a new design class of emergency vessels known as a “Liberty Ship.”

Rheem managed to build the freighter, and partially constructed a second ship, but the pace of shipbuilding was slow and efficiency was unsatisfactory, as judged by Maritime Commissioner inspectors who maintained an office on site. The contract with Rheem was terminated, and the shipyard was placed under the expertise of the Walsh-Kaiser Corporation. Its primary owner, Henry Kaiser, was recognized as one of the most brilliant industrialists in the country, having directed a variety of successful large-scale projects, including a major California shipyard. Walsh-Kaiser took over the Providence yard and there was immediate improvement.

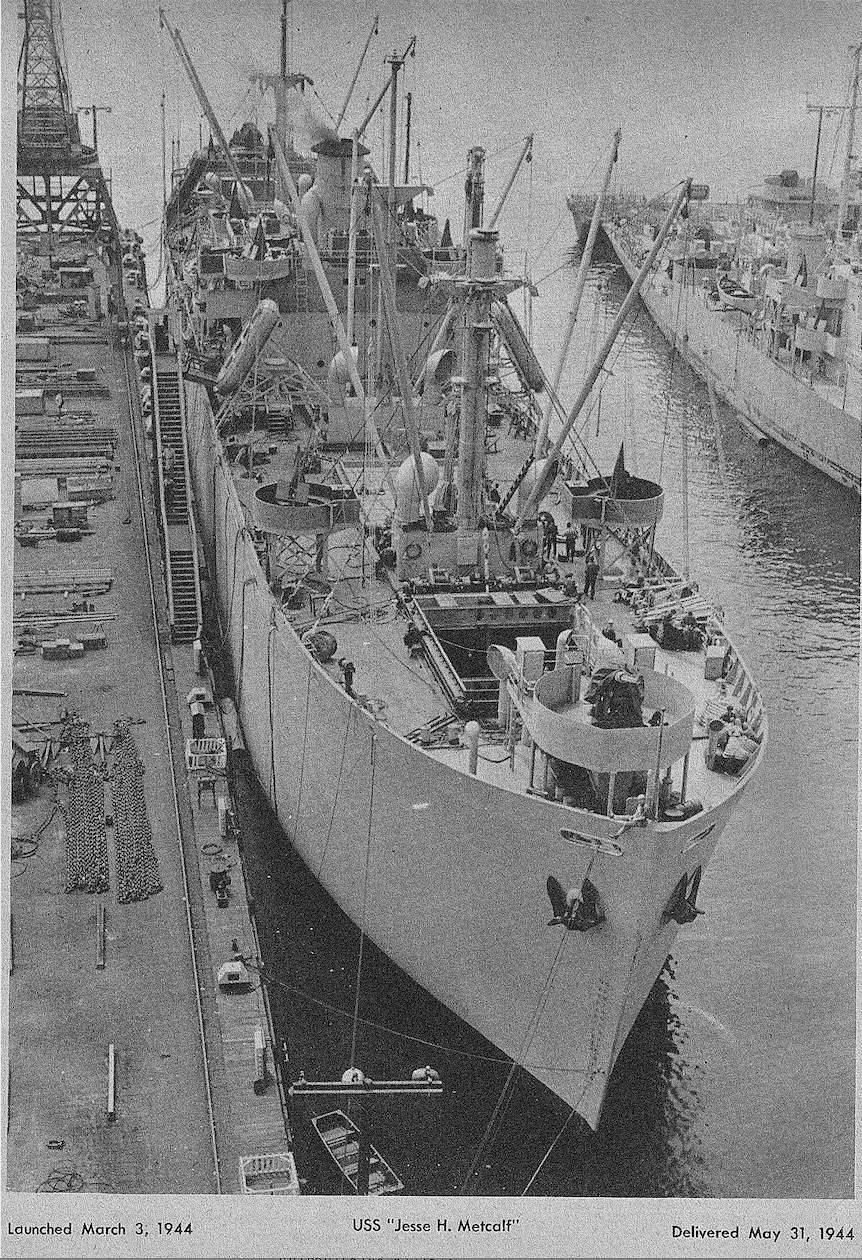

Launching of First Liberty Ship, SS William Coddington, November 28, 1942 (Rheem Manufacturing Company)

The shipyard site at Field’s Point occupied 144 acres. It was designed to be able to build six ships at a time. Six large “building ways” were erected side-by-side on the south facing waterfront. Numerous buildings were placed nearby for the assembly of prefabricated sections of ships. Large parking lots were available for employees who were fortunate enough to be able to own and operate automobiles during the years of severe gas rationing that existed during the war. The yard operated under flood lights 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Cranes in the sky appeared above South Providence.

At the peak of its existence the shipyard at Field’s Point employed more than 21,000 workers. Remarkably for the times, 3,000 of them were women. Although much of the work was physically demanding, and often dangerous, there was no problem finding workers. The pay of a shipyard worker was considerably greater than that being offered at any similar job outside. In 1944 the starting pay of a woman welder at the shipyard was 91 cents an hour. She would be fortunate to receive 50 to 70 cents an hour if employed at a local department store.

Another advantage of employment at the shipyard was exemption from military service, as long as work was available and job performance was satisfactory. However, if a male employee was laid off or fired for any reason, he would immediately be subject to the draft. There was, in fact, a military recruitment office on site at the personnel office. Simultaneous with receipt of his final pay envelope, the former employee received his draft notice. Within a few days he would be in uniform at a basic training facility. For some, this arrangement may have inspired a good work ethic.

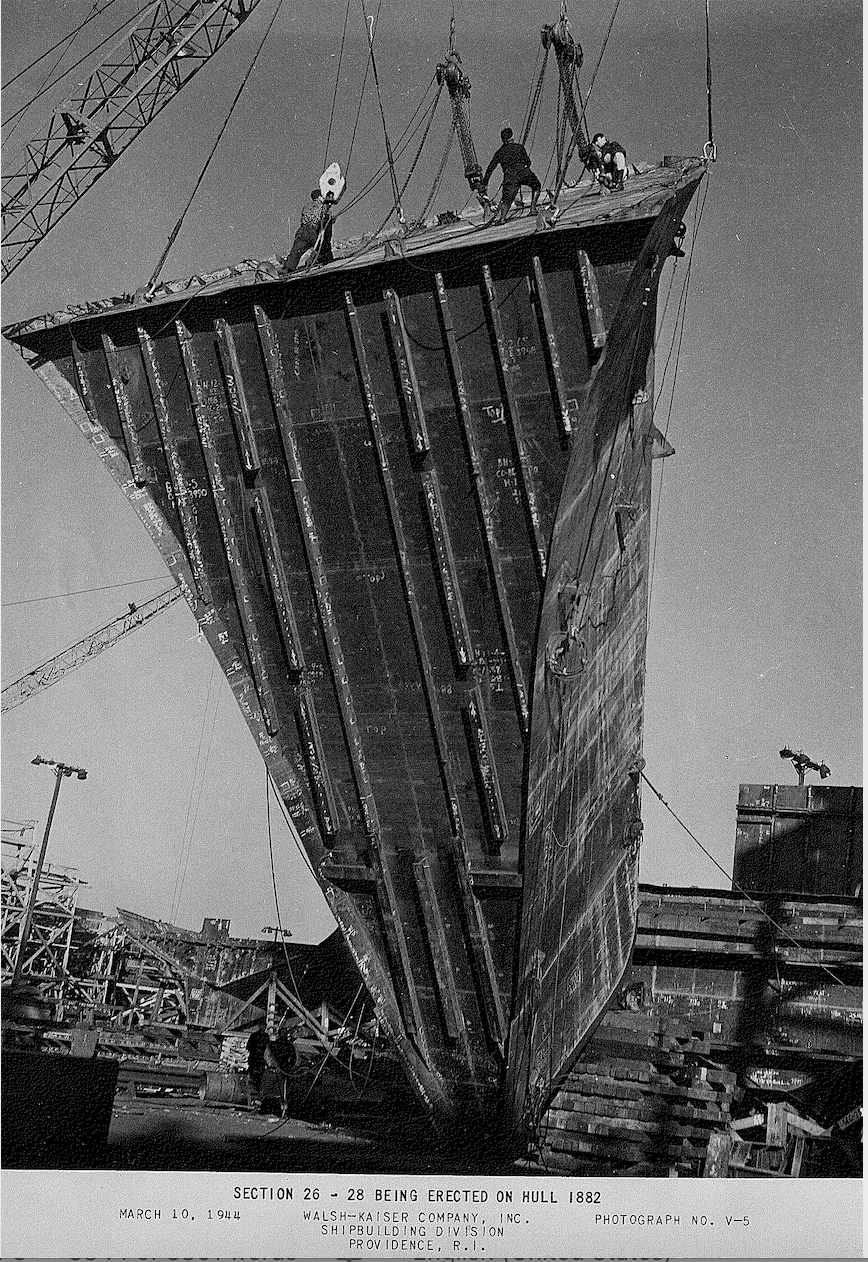

Section on Hull 1882 (USS Artemis) being erected. Fatalities were not uncommon, most from falling from heights. Note the apparent lack of safety harnesses or other protective devices (Walsh-Kaiser Company)

The master designs and specifications for ships created at the emergency yards came from professional naval architects contracted by the government. The Maritime Commission decided what types of ships would be assigned to each yard and sent the corresponding plans.

Providence was ordered to build three different types of ships. The first was the famous Liberty ship. In simple terms it was a huge, motorized, compartmented, floating “box” that could be loaded with every type of dry cargo needed at a distant shore. Nationwide, more than 2,700 “Liberties” were built during the war. Several of the emergency yards, including the one at South Portland, Maine, specialized in that design and produced hundreds. The Liberties from Providence were considered fill-in projects while awaiting material and supplies for the more significant ships. Field’s Point built just eleven Liberty ships.

The second ship design was a small warship designated a “frigate.” The frigate was intended to be used primarily as an escort vessel to protect convoys of merchant ships as they moved across oceans teeming with enemy submarines or overflown by enemy bomber aircraft. The frigate was equipped with sonar and radar, both being new, advanced technologies in the 1940s. Anti-submarine depth charges and anti-aircraft guns were included as armament. The U.S. Navy frigate was adapted from a Royal Navy design that had been conceived such that commercial shipyards, not experienced in warship construction, could produce a useful navy vessel without adhering to rigid military specifications. It was similar in size and appearance to another U.S. Navy type of warship known as a destroyer escort (which were invaluable in hunting German U-boats). More than one hundred frigates were built, some at shipyards on the Great Lakes. Providence delivered 21 of them.

Sea Trial of HMS Anguilla, a Tacoma Class Frigate, Transferred to the Royal Navy as Colony Class (Walsh-Kaiser Company)

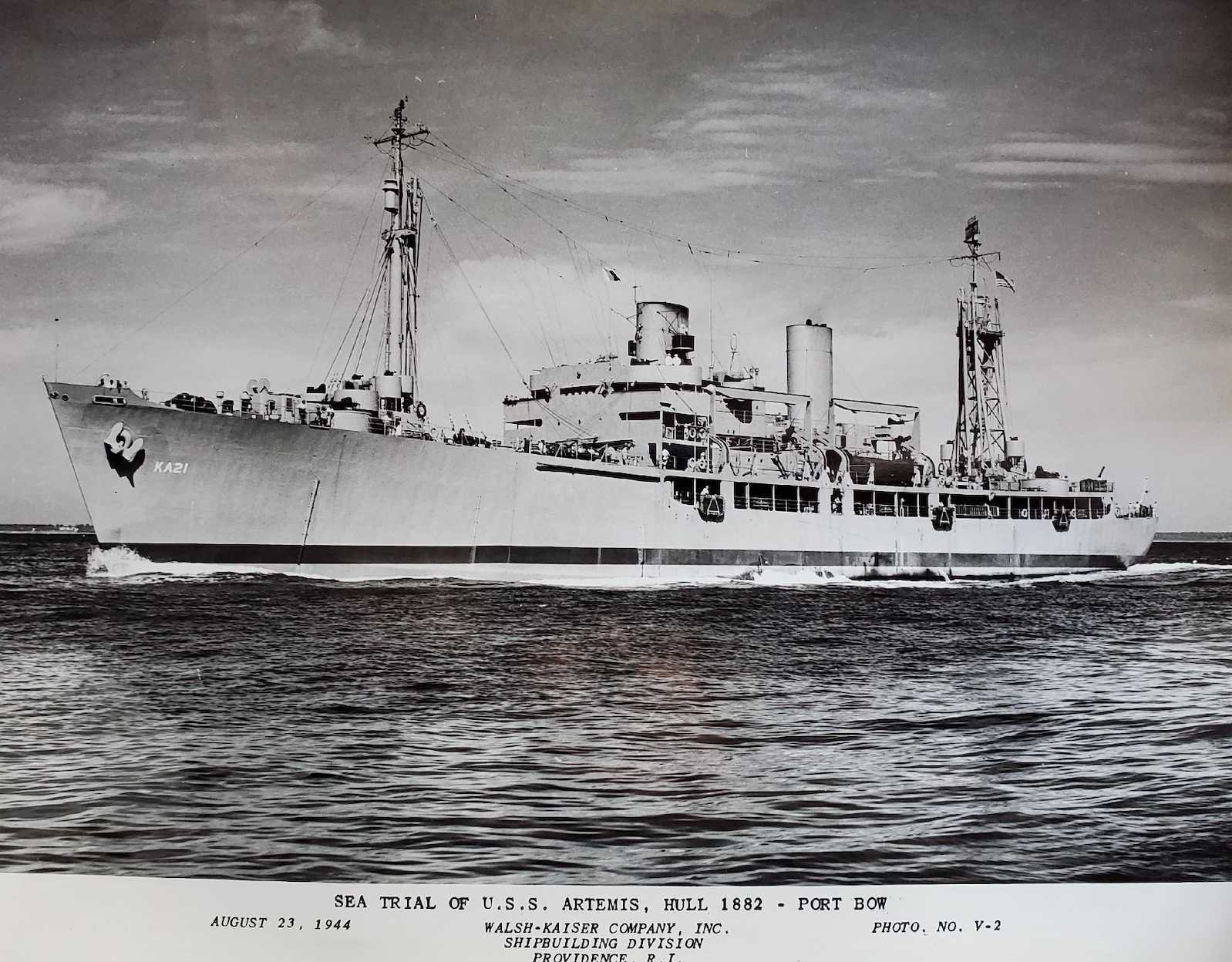

The third and largest Field’s Point product was a “Combat Loaded Cargo Ship.” It was also a new design, specially intended to support invasion of Japanese held islands in the Pacific Ocean. It was a U.S. Navy auxiliary vessel, identified as an AKA (auxiliary A, cargo K, attack A). It was configured to transport and land Army or Marine Corps troops on enemy beaches. Then it functioned as a floating supply depot, just offshore, to support the ground forces during their fighting. It was equipped with guns for defense against enemy air or surface craft. It also included modern medical facilities to treat wounded soldiers. The ship could transport 270 troops and set them ashore. The AKA carried fourteen landing craft, two of which were large enough to carry vehicles as large as a tank. Providence delivered 32 Combat Cargo Ships.

The Combat Cargo Ships, interestingly, were exclusive to Providence. No other yard built ships of that class of AKA. They were the most significant products of the Field’s Point shipyard.

The length of time required to build a ship varied widely. Histories of Liberty ships often boast of instances where a ship of that type was built in just a few days. That was not usual for shipbuilders experienced in constructing them; the simplicity of its design and efficient production methods resulted in impressive delivery records for many of those ships. The first Liberty built at Fields Point by the Rheem Corp. took eight months from keel laying to delivery. The others were completed in four months [shortest] to ten months. While not a record breaker, creation of a fully functional 440-foot-long cargo ship in four months is amazing. Cost of a brand-new ready-to-roll Liberty was $1,800,000 in 1940s money. That is equivalent to about $37,000,000 today. Such a deal. “Come On Down!”

Liberty ships were operated by civilian personnel. As soon as it was completed, the Maritime Commission assigned each new freighter to an established shipping company, under contract. That company was responsible for manning, operating, and maintaining the vessel until the end of the contract.

The crew of a Liberty numbered about 50 persons. They were civilian sailors, “Merchant Mariners” (not “Merchant Marines,” a frequently used misnomer). The ship’s officers were licensed, experienced men, but the lower ranking seamen often were new untrained sailors, fresh from the farms and factories of America. Many were attracted by the high pay given to merchant seamen, and to the fact that they were exempt from being drafted into military service as long as they maintained employment on a merchant ship. Later, many would realize that service on a Liberty ship could be more dangerous than that of a soldier in a foxhole ashore. (The Merchant Marine had a higher death rate during the war than the Army or Navy).

A Liberty’s crew was augmented by a detachment of U.S. Navy personnel when sailing in dangerous areas of the world (which was just about everywhere during the war). Such U.S. Navy personnel were known as the ship’s Armed Guard.

During the war, most merchant ships were outfitted with several guns for defense against surfaced submarines and enemy aircraft. It was considered inappropriate or illegal to require civilian crew members to operate guns in combat. Therefore, a navy military team, trained in operation and maintenance of the guns, was assigned to each armed merchant ship. The Armed Guard unit consisted of about 25 men, commanded by a single junior commissioned officer (Ensign or Lieutenant, junior grade). With the Armed Guard on board, a Liberty sailed with about 70 to 80 persons.

In contrast, the crew of a frigate was entirely military. The U.S. Navy frigates were somewhat unusual in that their personnel were often entirely made up of U.S. Coast Guard personnel. During World War II, the Coast Guard was absorbed by the Navy and operated under Navy control. The frigates from Field’s Point were otherwise unique in that they were manned by British crews. That entire group of 21 ships was given to the Royal Navy under the Lend-Lease program. While the ships were being built, Royal Navy sailors were stationed at Boston for training, and then sent to Providence to join their ships as they were completed and commissioned as British warships

Getting to America from England during the war was a dangerous trip. Travel by airplane was not possible. Usually, the British crews were sent on ships headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. There they boarded trains for Boston. Each British frigate had a crew of about 170 men. Most of the officers, including the commanding officer, were navy reservists. The captain of a frigate held the rank of lieutenant commander (equivalent to a major in other services).

The Combat Cargo Ships were large and loaded with sophisticated features. They required a crew of 303 U.S. Navy military personnel. The senior officer was usually a full commander. The background of those men included long service career sailors, reservists called to active duty, and men who enlisted or were drafted into the Navy. Most were, or became, competent in the numerous special skills required for deploying an AKA. Included were doctors and dentists who closed their civilian practices and accepted officer commissions for the duration of the war.

The Combat Cargo Ship was a floating “village” that could respond to most any need for long periods of time. With troops embarked, an AKA carried nearly six hundred men.

The appearance of the ship was impressive. Having two streamlined smokestacks, it resembled an ocean liner.

One of the details associated with shipbuilding, considered to be of importance, was the naming of the ships. Despite the turbulent demands and distractions of a world war, a great amount of thought and attention was given to assigning appropriate names to all the new ships being built. In the case of the Liberty ships, the government invited input from the shipbuilders to recommend names that honored local historical persons. The only stipulation was that they must be deceased. Existing political figures were not to be considered.

The first Liberty ship launched at Providence, SS William Coddington, was named for one of the early settlers of Aquidneck Island. Then there were SS John Clarke, SS Samuel Gorton, and SS Moses Brown, all named for historical figures from Rhode Island’s colonial and revolutionary period.

The prefix SS means Steam Ship. When a ship was finished its name was painted on each side of the bow [without the SS] and across the stern. After it began operating, the Liberty’s name might be painted over for security reasons.

When the new class of frigates was authorized, the U.S. Navy assigned names and hull numbers to each. They were all given names of small cities throughout the United States. Included was a USS Newport, a USS New Bedford, and a USS Woonsocket. Here, the prefix USS means United States Ship. The entire class of frigates was known as the Tacoma Class, USS Tacoma being the name of the first ship of that class or group of identical vessels.

When it was decided to give 21 of the frigates to the British, it was obvious that American names would not be appropriate. After considerable discussion, the Admiralty in London sent over a list of names. The Field’s Point frigates were to be named after some less important colonies (many small islands) of the British empire. The entire set would be known as Colony Class frigates. Included were HMS Pitcairn, HMS Barbados, and HMS Zanzibar. The HMS designation was, of course, for His Majesty’s Ship.

Naming the Combat Cargo Ships was a perplexing problem. There were so many auxiliary vessels, of similar function, that officials were running out of ideas for names that fit a logical category, such as people or places. Finally, someone suggested naming the Providence AKA ships after heavenly bodies. There are numerous stars, constellations, and other objects in the universe known only to astronomers. They have names that could be used for ships. The first AKA completed at Field’s Point was given the name USS Artemis. Therefore, all 32 would be known as the Artemis Class Combat Cargo Ships. Others included USS Hydrus, USS Lumen, and USS Xenia. With each name of a navy ship there is a corresponding hull number. The name appears only on the stern of the ship, At the bow, the hull number is painted in white. Artemis vessels included the letters KA with the numerals.

Production efficiency at the shipyard improved continually, despite construction materiel shortages causing delays. There were also unexpected problems such as an inherent mechanical issue with the propeller shaft bearings of the frigates. Solving that problem involved time consuming changes and trials. However, all 21 Colony Class ships were delivered between October 1943 and June 1944, an impressive accomplishment. After that, the production record of the Artemis Class ships emerged as nothing less than spectacular.

The keel of the first ship was laid in November 1943, and delivery was in August 1944. That was not bad for the first ship of a new design, but the Navy was desperate to have those ships and wanted them built even faster. The yard workers and their unions were made to understand how important it was, and they responded with patriotic drive. A goal was set to complete ten ships before the end of 1944. That goal was met. The yard earned the award of a large Maritime Commission pennant to be flown with the U.S. flag and the Victory flag at its headquarters. The white letter M against a blue field was the highest form of recognition that could be given to a facility involved in navy production work. Each employee received a Maritime Commission award of merit pin to recognize his/her contribution to the shipyard’s achievement.

The ships continued to be completed at an astonishing rate. In 1945, a new Artemis AKA was delivered, on average, once every ten days. The most impressive record was set when two of the ships, USS Turnadot and USS Valeria, were each built from keel laying to delivery in just 82 days. From November 1943 to August 1945 the shipyard constructed 32 huge Artemis Class Combat Cargo ships (AKA 21 to AKA 52).

Delivery and commissioning of the last ship, USS Zenobia (AKA 52), was on August 6, 1945. That was also the day when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. Shortly thereafter, World War II ended. Delivery of AKA 52 meant that there was nothing more to do at the shipyard. Local politicians, envisioning Providence as a major shipbuilding center in post-war years, tried to get the government to maintain the yard, but all their lobbying failed. Within a few months the building ways and other structures were torn down. The site of the shipyard became an overgrown area of wild brush amidst assorted rusting junk. It remained that way for many years.

The emergency shipyard at Field’s Point delivered 64 ships. It was an important contribution by the local labor force towards winning World War II. During the 1940s there was little in the way of industrial automation. Those ships were built by people, not machines. The effort of those many persons should not be ignored or forgotten. Sadly, there is nothing at the site of the yard that commemorates their work. There is no monument, plaque, or other marker that mentions the historical significance of that place.

Today there is nothing left that suggests the onetime existence of a shipyard at Field’s Point. The last vestige of it was a row of weathered pilings in the water where a fitting out pier once stood. A portion of the property is now the waterfront campus of Johnson and Wales University. It is doubtful that any of the students or faculty of that institution are aware of what was accomplished there during the war.

The news media has not been useful in reporting the history of the Field’s Point shipyard. Whenever it has been mentioned by the press, the story has been full of errors. The most characteristic mistake is undue emphasis on the Liberty ships. If the yard is mentioned at all, it usually is described as “the place that built the Liberty ships.” As explained earlier in this article, the Liberties were a minor set of the products constructed at Providence. That error was exemplified recently when a book was published that features nostalgic photographs of Rhode Island during the 1940s. Included is a high-altitude aerial picture of the shipyard. It shows ships in all six of the building ways. They are proudly described as Liberty ships in the caption. In fact, it is clear that all are Combat Cargo Ships. No image of a Liberty exists in that picture.

The Artemis AKA, especially, should be remembered when the industrial contributions of Rhode Island are cited in World War II histories. It was unique to the Field’s Point shipyard. No other yard built it. During the war years, it was synonymous with Providence.

So ends my summary of the subject of shipbuilding at Providence during World War II. But that is only part of the larger story that describes the operations and disposition of those 64 ships. Readers may wonder what happened to all those vessels when they sailed down Narragansett Bay and went away to serve on the path to victory. The whole story is included in my book, The Ships from Field’s Point, Providence RI 1942-1945. Therein is an account of the service and adventures of many of those ships, during the war and in the years following it. There is also a record of the final disposition of each vessel.

Notes on Sources

Most sources are presented on pages 161-165 of The Ships from Field’s Point. It is not practical to repeat all those listings here. In addition, I was privileged to have the opportunity to interview two former shipyard employees. One was a telephone conversation with an elderly lady who, in her late teens, had been a welder. The other was an in-person meeting with a gentleman who had worked in the cable assembly shop.