In the early days of the abolition movement in the United States, by necessity, abolitionist work had to come primarily from white people because, before the American Revolution, most black people were enslaved. But on occasion enslaved black people forced the hands of whites and in turn advanced the cause of abolitionism. This is the story Abigail, an enslaved woman from South Kingstown, who did exactly that in 1779.

As is typically the case with enslaved people fighting for their rights, the story is complicated and the motivations of the main characters are mixed, but the story is fascinating. While the outlines of this story have been mentioned in other history books, the author of this article has uncovered much new information, including contemporary documents. In addition, this article includes the first detailed discussion of the 1779 law ever published, including its remarkable recital supporting eventual abolition of slavery in the state.

The American Revolution was the world’s first significant movement in abolishing slavery. Before then, there was virtually no antislavery activity in any of the thirteen colonies of North America, or for that matter, anywhere else in the world. There was some antislavery activity percolating in Britain, but the abolition movement there did not begin until 1787.

Patriots loudly proclaiming infringements on their liberties by the British Crown could not help but see and sympathize with enslaved people who lived in their midst possessing almost no rights. Along with the rising desire to free themselves from British rule, some white people in the Northern colonies, and even a few in the Southern colonies, began to feel the first stirrings of antislavery thought.

The abolition movement took a long road. Progress was usually incremental. It was not realistic to expect all thirteen colonies, or even the northern ones, to make an abrupt transition concerning an institution that had existed worldwide in various forms for thousands of years. But by the end of the period that felt the impact of the American Revolution, progress in the cause of abolition (and ending the transatlantic slave trade) had definitely been made.

Rhode Island saw its own antislavery movement arise in the years before the American Revolution, even though the colony continued to dominate the North American slave trade (mostly from Newport) and had the highest percentage of blacks of any New England colony (more than six percent). Rhode Island’s blacks were centered in Newport, Providence and in what is now Washington County (then known as King’s County and now also known as South County), where a quasi-plantation system of dairy, livestock and horse farms arose and where enslaved people dominated the workforce.[1]

By the eve of the American Revolution, Stephen Hopkins and Moses Brown of Providence, and the Reverend Samuel Hopkins (no relation) of Newport, became a powerful triumvirate in Rhode Island opposing both the slave trade and the institution of slavery. Stephen Hopkins, a four-time governor of the colony and future signer of the Declaration of Independence, had owned an enslaved woman whom he said cared for his ailing wife and children. But his views had evolved. Moses Brown also had been a slave owner, but after converting to the Society of Friends (Quakers), he manumitted them. The Reverend Samuel Hopkins too once owned an enslaved person. Yet he became perhaps the most impassioned antislavery writer in the colonies, even if he was the minister of a Congregationalist congregation in Newport, the slave trading capital of the colonies. (He did not allow slave trading merchants or slave ship captains in his congregation). The three men knew that because Rhode Island did not have a royal governor, its legislature, the General Assembly, could enact antislavery bills without the need for royal approval, and that because the colony was so small, officials in London might overlook the laws.

On May 17, 1774, the town meeting of Providence recommended a stoppage of “all trade with Great Britain, Ireland, Africa and the West Indies.” The ban would prohibit Rhode Islanders from carrying African captives to British-controlled Caribbean islands (which was where most Rhode Island slave ship captains carried them). The town meeting further instructed its representatives to the Rhode Island General Assembly to obtain an act banning the importation of enslaved people, and to free all enslaved persons born in the colony after they reached maturity.[2]

With Stephen Hopkins and Moses Brown working behind the scenes, the General Assembly at least complied with one request, banishing the importation of African captives in June of that same year. This was one of the first times in world history—and perhaps the first—that a legislature adopted a material measure restricting the transatlantic slave trade.

The act’s recital, likely penned by Stephen Hopkins, was impressive, even if it likely referred to the gradual emancipation proposal that was not adopted:

Whereas, the inhabitants of America are generally engaged in the preservation of their own rights and liberties, among which, that of personal freedom must be considered as the greatest; as those who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves should be willing to extend personal liberty to others.[3]

The two Hopkinses and Brown were disappointed that the General Assembly did not pass legislation gradually emancipating Rhode Island’s enslaved population. With the coming of the movement for independence against Great Britain and the need to unite in the long war against the British, the new states of the United States generally set aside for later consideration controversial matters such as emancipation. That was the case with Rhode Island, which did not enact its gradual emancipation bill until 1784, the year after the Revolutionary War ended.

Once the war commenced in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, enslaved people in Rhode Island found opportunities to gain their freedom, further weakening the institution of slavery in the state. Enslaved men could often earn their freedom by substituting for their white owners who had received draft notices to serve in the state militia. Beginning in February 1778, with the re-establishment of the First Rhode Island Continental Regiment (the famous “Black Regiment”), about one hundred enslaved men earned their freedom by enlisting. Moreover, as I documented in an article for Newport History magazine, at least thirty-five enslaved men, women and children, and likely dozens more, escaped from the Rhode Island mainland to Newport and Aquidneck Island, then occupied by the British army and navy. Many of them left the state and after the war were resettled in Canada.[4]

About 100 enslaved men earned their freedom by enlisting and serving in the First Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals during the Revolutionary War (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

The focus of this article is on an incident in 1779, when an enslaved woman, Abigail (also called Nab), from South Kingstown, forced the General Assembly’s hands.

The story begins in the spring of 1779 with John Rice, of Hartford, in Orange County, in North Carolina, travelling to New England. His aim: to purchase enslaved people and bring them back to his home state. Whether he wanted to use the enslaved people on his own farm in North Carolina or to resell them at a profit to other farmers in North Carolina is not known. Because the Continental Congress had shut down the transatlantic slave trade during the war, North Carolina was not allowed to import any captives from Africa or any other place.[5]

Rice was an ambitious twenty-five year-old. A stranger in New England, he carried in his pocket a letter of recommendation from John Penn, a delegate to the Continental Congress from North Carolina, who wrote that Rice “is esteemed as a young man of character.” Penn added that he hoped Rice would “tak[e] care to behave well.”[6]

Rice must have suspected he would face opposition if he announced that he hailed from North Carolina and wanted to purchase enslaved people and bring them back. While slavery in Rhode Island and the rest of New England on occasion could be harsh, the conditions of enslaved people in Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, and especially in South Carolina and Georgia, were known to be much worse. Of course, slavery anywhere was horrible and had to be enforced by local laws and terror. But conditions of servitude in the South were more brutal than those in the North, particularly compared to conditions in New England. In addition, some thought it cruel to take enslaved people away from their families. Accordingly, Rice told people he encountered that he hailed from Hartford—in Connecticut.

Perhaps Rice thought he could obtain some “deals” in Rhode Island. At the time, the British army occupied Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island, as well as Jamestown. With the Royal Navy capturing American trading vessels by the score, trade was depressed. So called “Narragansett Planters” in King’s County had less ability to profit from keeping enslaved people.. In addition, astute slaveholders might have seen the writing on the wall—that slavery would soon end in the state. One solution was to obtain some money by selling them. Since the market within Rhode Island was poor due to hard economic times, a likely buyer would be from out-of-state.

On May 13, 1779, John Rice appeared at the farm of Carder Hazard of South Kingstown (which then included the town of Narragansett). Hazard, a second son, reportedly was tall and “uncommonly handsome.” He was a moderately successful farmer and a slave owner whose first wife hailed from the South. At the time he was one of five justices on the King’s County Court of Common Pleas, having served several terms in that position.[7]

Hazard agreed to sell Rice four of his enslaved females: Abigail and three of her young daughters, Mary, Jane and Milly. The eldest of the three girls was just seven years old. Rice must have been desperate to buy as he paid the $3,000 purchase price not only in depreciated Continental paper money, but also with “hard money”—scarce and valuable Spanish milled coins.[8]

It is not known if Hazard knew that Rice intended to take Abigail and her children to North Carolina. At the least, Hazard must have known that Rice was not from Rhode Island. It is possible Rice told him he was taking them to Hartford, Connecticut. Even if he did, that was a long horse ride from Narragansett, away from Abigail’s family.

The identity of the father of Abigail’s children is never mentioned in the record. It is possible he was one of Carder Hazard’s enslaved men. In November 1777, three of Hazard’s enslaved men—Jacob, Pharoah and Quaco—were spotted helping to unload a British warship that had accidentally run ashore near Point Judith. Perhaps it was Jacob, who on July 6, 1778 enlisted in the First Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals, thereby earning his freedom, but who was away on military duty.[9]

Rice was eager to travel to other states in New England, probably Connecticut and/or Massachusetts, to search for more enslaved people to buy. He did not want to have Abigail and her young children tag along with him. So he left Abigail and her children behind at Carder Hazard’s farm until he returned to fetch them.

On June 18, Rice returned to South Kingstown (probably in current day Narragansett) to pick up Abigail and her girls in order to transport them to the South in a wagon he had acquired. Other enslaved people whom Rice had purchased out of state were already in the wagon.

Rice hired two men to drive the wagon, thirty-year-old Lodowick Stanton of Charlestown and John Cross of Westerly. The thirty-year-old Stanton was the son of Colonel Joseph Stanton of Charlestown, a prominent farmer and slave holder. But because thirty-year-old Lodowick was the third son and sixth child, and his father was still living on the main family farm, it appears he was not a substantial farmer. Most successful farmers would not have hired themselves out as a wagon driver. Cross was a peddler and small-time merchant.[10]

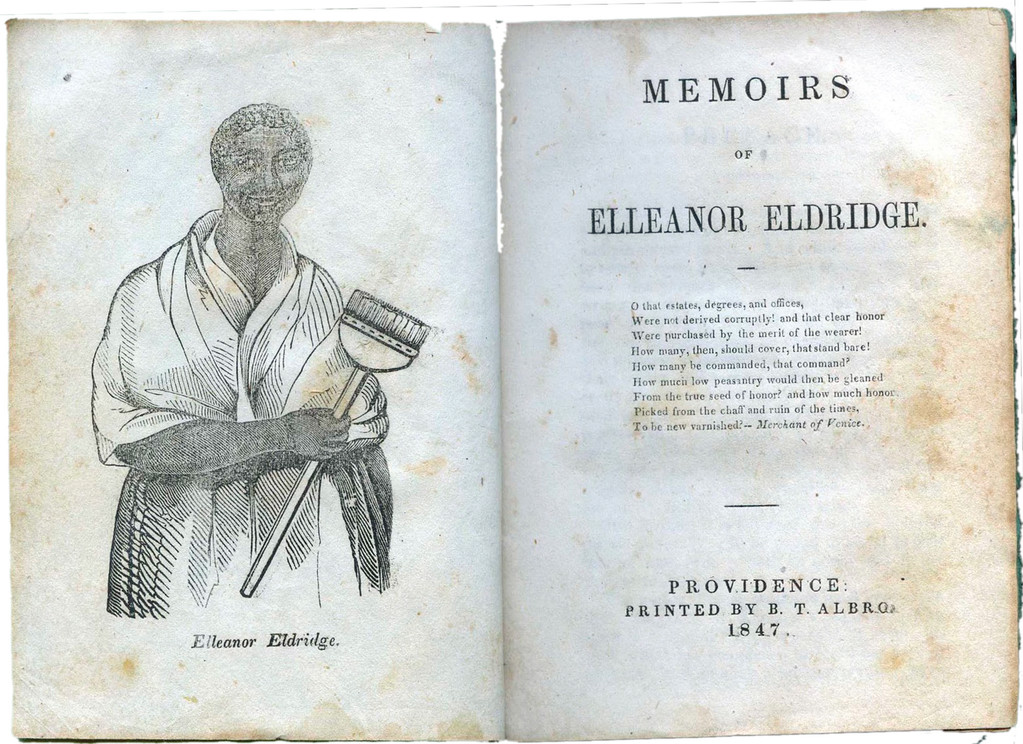

Elleanor Elldridge, a daughter of an enslaved Rhode Island woman, had her memoir published in Providence in 1838 (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

The next day, Rice and his party, including his wagon filled with enslaved men, women and children, rode southwest, probably mostly along the Old Post Road. Cross took one of Abigail’s children on his horse, and Stanton drove the wagon carrying Abigail and her two other children.

During the day’s ride, which was about thirteen miles, Abigail and Lodowick must have discussed that she and her daughters were being taken to North Carolina. Abigail must have disclosed strong feelings against it and asked Lodowick if he could help her and her children avoid that fate so that they could remain in Rhode Island. Stanton decided to help Abigail.

The party arrived in the early afternoon at Stanton’s house in Charlestown. Stanton discussed his plans with his wife, Thankful, who must have agreed to cooperate with her husband to aid Abigail. Stanton then walked into the room where Rice was resting and announced that he wanted to purchase Abigail and her youngest daughter, Milly. This was a surprising offer, since Stanton did not appear to be a wealthy man and is not reported to have held any enslaved people. Stanton may have figured that this was the only way to keep the two in Rhode Island. Rice refused. Stanton pressed him again, but Rice’s denial was firm.

Stanton left Rice and went to a back room to speak with Abigail, who must have known about Stanton’s offer to purchase her. The two agreed on another plan. Abigail then approached Rice and said that she wanted to stay nearby at John Cross’s house for the night. Her third child might have been at Cross’s house. Lodowick Stanton then said he would be a surety for Abigail’s return. Thankful, in a friendly manner, next offered for Rice to spend the night at their house for free. Rice accepted the offer, and although he feared that Abigail might never return to him, he apparently agreed that she (and presumably her children) spend the night nearby at Cross’s house. In the meantime, Stanton departed his house, claiming that he had business at a nearby mill. In reality, he was making plans with Cross and likely other locals to assist Abigail and her daughters.

Shortly after sundown, the Stantons informed Rice that they were going to bed for the night. Rice decided to get a good sleep as well; he was weary from the trip. But Lodowick must have sneaked away from his house at night to assist Abigail and her children.[11]

The next morning Rice awoke and was informed that Abigail and her daughters were nowhere to be found. Stanton was not a good liar. At first he said that they had all gone to Block Island. Then he blamed John Cross for their disappearance.

In a petition Rice later submitted to the General Assembly, he stated: “In making enquiry for his Negroes, [he] has great reasons to believe that a number of people had combined against him to deprive him of his property.” In addition, Rice wrote that he “was informed his person was in danger if he . . . pursued after” Abigail and her children. Stanton and likely John Cross, among others, kept Abigail and her children hidden at their own expense for several weeks.

A frustrated Rice continued on to Stonington, Connecticut, where he entered into a power of attorney authorizing a Stonington attorney, Joshua Randall, to recover his lost “property.” After travelling around New England to find more enslaved people to purchase, on September 11 Rice arrived at New London, Connecticut, expecting to find Abigail and her children there. He was disappointed.[12]

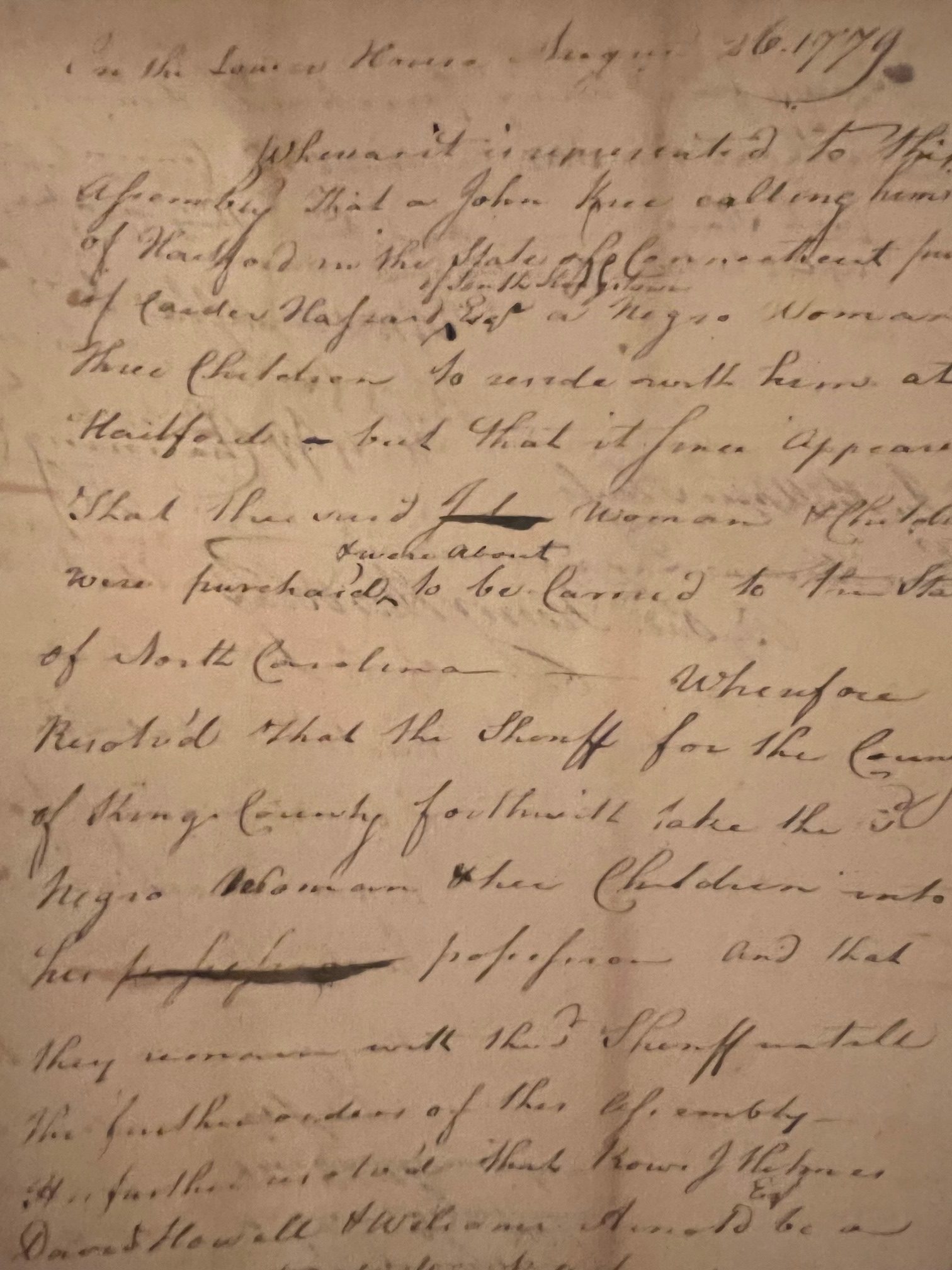

Rice was informed of the proceedings involving Abigail and her girls at the August 1779 session of the General Assembly at Providence. Some white men from southern Rhode Island, likely including Lodowick Stanton, approached the General Assembly and informed its members of Abigail’s circumstances. In response, the General Assembly passed the following resolution:

Whereas, it is represented unto this Assembly, that Joshua Randall, of Stonington, in the state of Connecticut, as factor for one John Rice, calling himself of Hartford, in the state of Connecticut, aforesaid, purchased of Carder Hazard, of South Kingstown, Esq., a negro woman, and three children, to reside with the said John Rice, at Hartford [meaning in Connecticut]; but that since it appeareth that the said woman and children were purchased to be carried to the state of North Carolina; wherefore—

It is voted and resolved, that the sheriff of the county of Kings forthwith take the said negro woman and her children into his possession; and that they remain with the said sheriff until further orders of this Assembly.[13]

From the Journal of the Lower House of the General Assembly, August 26, 1779. The resolution directs that Abigail and her daughters not be taken out of the state by John Rice and instead be in the custody of the sheriff of King’s County (Rhode Island State Archives)

Perhaps hearing of Rice’s arrival at nearby New London, the General Assembly, then meeting at the courthouse at East Greenwich, again took up Abigail’s cause. On September 15, the Lower House of the General Assembly ordered Joshua Randall of Stonington to sell “the Negro woman and her 3 children” to a Rhode Island resident or residents whose “humanity shall be approved of by Carder Hazard of South Kingstown, the original owner of said slaves,” that in the meantime Abigail and her children should continue to be held in the custody of the Sheriff of King’s County, Beriah Brown of North Kingstown, and that Rice pay Brown for the cost of the food and other expenses incurred in maintaining Abigail and her children until the sale was completed.[14]

The General Assembly might have decided to void the sale by Carder Hazard, forcing him to return all of the purchase price to Rice. But it did not take that course, possibly not believing it could interfere with a private contract, or preferring to be severe with an out-of-state slaver.

An outraged Rice, learning about the proceedings at East Greenwich, rushed to the town, arriving on the morning of September 17, but he was too late. The General Assembly had resolved not to conduct any more private business.[15]

Rice complained, in his petition, that “such a noise is made and propagated by designing men” about his character that he “must lose his said property unless” the Lower House reversed itself. On October 28, Rice submitted his petition to the General Assembly, then meeting in session at the courthouse in Little Rest (still standing in what is now Kingston, in South Kingstown), and asked for the General Assembly to grant him appropriate relief.[16]

The General Assembly did not look kindly upon Rice’s petition or request for relief, refusing to change its position. Instead, it passed new legislation prohibiting the sale of enslaved people to out-of-state buyers without the consent of the enslaved people.

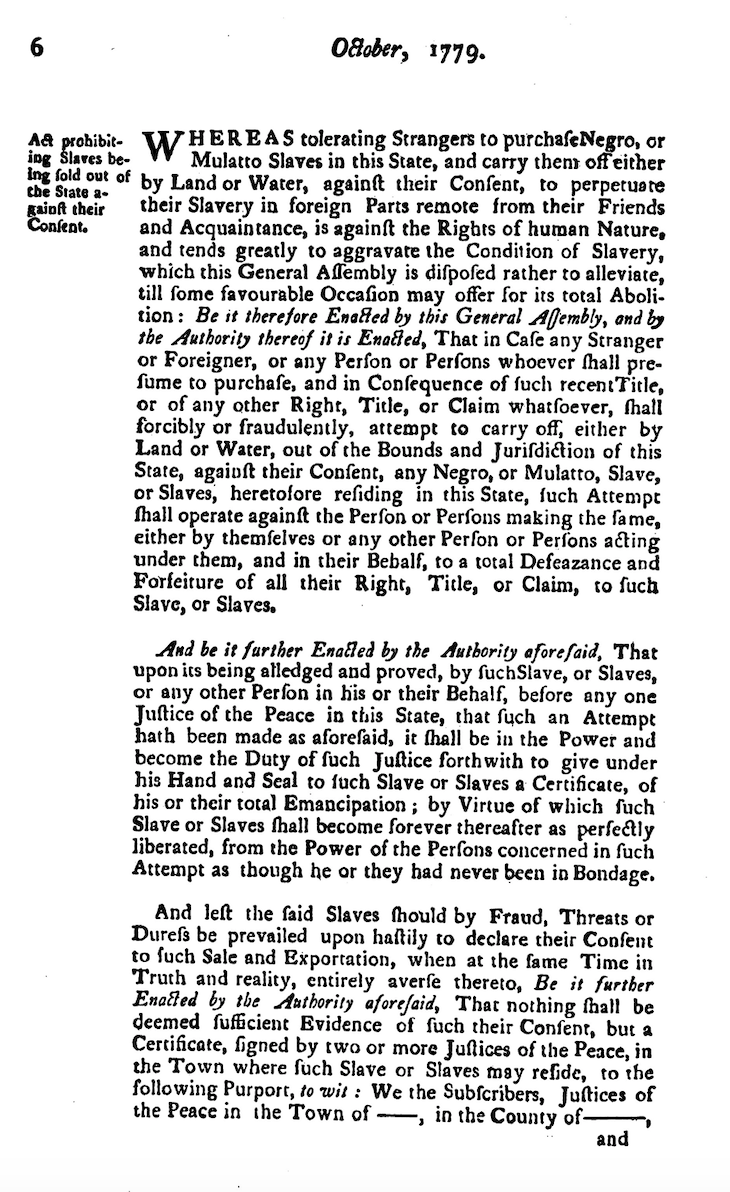

This article is the first time that the legislation’s recital and other parts of the act are set forth in a publication. Historians previously relied on John Russell Bartlett’s Records of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, but volume eight of that work gives only the act’s name and purpose. For the full text of the Act, one must consult the Rhode Island State Archives or the hard-to-find published work, Rhode Island Resolves and Acts.

The General Assembly included with the legislation a remarkable recital:

Whereas tolerating Strangers to purchase Negroes, or Mulatto Slaves in this State, and carry them off either by Land or Water, against their consent, to perpetuate their Slavery in foreign Parts remote from their Friends and Acquaintance[s], is against the Rights of human Nature, and tends greatly to aggravate the Condition of Slavery, which this General Assembly is disposed to alleviate, till some favorable Occasion may offer for its total Abolition . . . .[17]

This recital is remarkable for two reasons. First is the rationale provided for it: that it was cruel for an enslaved Rhode Islander to be carried away to a different state far from the person’s family and friends. Previously, most historians have concluded that the main rationale for legislation such as this (which was adopted in several northern states) was the legislators’ determination that the conditions of enslavement were harsher in the South than in the North.

In addition, the recital refers to the disposition of the General Assembly to lessen the harshness of the conditions of enslavement until “some favorable occasion may offer for its total Abolition.” The occasion, no doubt, was a successful end to the war of independence against Great Britain. As stated, Rhode Island did enact a gradual emancipation act in 1784, the year after the war’s end.

Back in the General Assembly’s August 1779 session, David Howell, Welcome Arnold and Rouse J. Helme had been appointed a committee to draft this bill. David Howell of Providence was the first name to appear in a list of members of the Providence Abolition Society, formed in June 1790,[18] and he took an active role in leading it. One suspects he drafted the above recital.

First page of an “Act Prohibiting Slaves being Sold Out of State Against Their Consent”, with its remarkable recital (R.I. Acts & Resolves, Oct. 1779)

Remarkably, the legislation included a provision that if an enslaved person complained to a Justice of the Peace in any town in the state, and it was proven, that there had been an attempt to sell such enslaved person and have the person carried outside the state without such person’s consent, in violation of the act, the Justice of the Peace was required to provide the enslaved person “a Certificate, of his or her total Emancipation; by Virtue of which such slave or slaves shall become forever thereafter as perfectly liberated . . . as though he or they had never been in Bondage.”[19]

This part of the legislation is evidence that the members of the General Assembly would have liked to have emancipated Abigail and her daughters. However, they must have felt it was not fair to apply the law retroactively without having given John Rice notice of the act before applying it.

In addition, if any slave buyer was convicted in court of violating the law, such person would be required to pay a fine equal to the value of the enslaved person or persons that the convicted person attempted to sell. And one-half of such fine was to be paid to the “Informer” whose information led to the conviction.

The law contained another provision that must have been added as a sop to, or made at the insistent of, Rhode Island slaveholders. A Rhode Island slaveholder could sell outside the state an enslaved person who had “become notoriously unfaithful and villainous.” To do so, the slaveholder had to obtain a judgment in the county court that the enslaved man or woman satisfied this standard—not an easy burden to fulfill. It is not clear if an enslaved man or woman would be considered “unfaithful and villainous” if he or she tried to free himself or herself by running away.[20]

I am not are of any cases applying the emancipation provision or the provision imposing a fine on slaveholders who attempted to sell an enslaved person out of state. Thanks to the Rhode Island State Archives, I am aware of one case in which a slave owner successfully petitioned the General Assembly under the provision described in the above paragraph to sell an enslaved woman to a Connecticut buyer, but that is a story for another day.

John Rice must have been dumb-founded about the legislation. To make matters worse for Rice, on the same day that Rice submitted his petition and the law was passed, Abigail and her three children were sold to two Rhode Islanders. Lodowick Stanton purchased Abigail and her daughter Milly. The other two girls, Mary and Jane, were purchased by Colonel Joseph Noyes, a prominent militia officer and farmer from Westerly whose farm was located near the coast.[21]

In the Rhode Island censuses of 1774 and 1782, and the federal censuses of 1790 and 1800, Lodowick Stanton is not reported as having any black persons living in his household, either enslaved or free.[22] Interestingly, those censuses do not indicate that his oldest brother, Joseph Stanton, Jr., who would be elected as one of the state’s first U.S. Senators in 1790, ever held any enslaved people. Joseph Stanton, Jr. was also an original member of the Providence Abolition Society. Did Lodowick purchase Abigail and Milly for humanitarian purposes? Or was he from the start motivated to purchase Abigail and one of his daughters to enslave them? It will never be known with certainty, but his conduct with Rice on the day before Abigail’s escape, the census information, and his oldest brother’s activities, constitute some evidence that it was the former.

By contrast, Joseph Noyes was reported to have five black persons in his household in the 1774 census and three in the 1782 census, all of whom were likely enslaved. In the 1790 census, Noyes is listed as having seven enslaved persons residing in his household; in the 1800 census, none are reported.[23]

The General Assembly required both Stanton and Noyes to sign a bond obligating them to “not send said Negroes or either of them out of this State.” The penalty for failing to comply with this obligation was $10,000.[24]

For Abigail, the outcome was mixed. On the positive side, neither she nor any of her children was transported to North Carolina. In addition, her actions helped spur legislation in the General Assembly that could be applied to help other enslaved people in Rhode Island. On the other hand, tragically, her family was divided. Stanton could not afford to purchase all of Abigail’s children. Stanton’s and Noyes’s farms were not too far away from each other, but still she could not see Mary and Jane on a daily basis. (It is possible Noyes allowed Abigail to look after the two young girls he had purchased until they became old enough to work at his farm or house).

The General Assembly’s 1779 legislation did not apply retroactively the provisions allowing an enslaved person who filed a complaint about being sold out of state to be declared free. If it had, Abigail could have gone free. In addition, Rhode Island’s gradual emancipation legislation, enacted in 1784, technically applied only to persons born of enslaved mothers after the date of the act.[25] That was too late for Abigail (and her children) too.

In actuality, the institution of slavery in Rhode Island was weakened at a more accelerated rate than the gradual emancipation law envisioned. In 1774, there were likely more than 3,000 enslaved persons in Rhode Island, but by 1790 there were only 948 and by 1800 just 380. Most enslaved persons in Rhode Island had been freed, either by manumission by their owners, by their owners through negotiations with the enslaved adults, or by the enslaved persons freeing themselves by running away. Some slave holders stubbornly held on, but many of those who remained enslaved were elderly, who may not have been able to support themselves if freed, and children born after 1784 who would eventually become free. It is likely the case that Abigail’s children were not freed until they attained age 21 or later so that they could work to support themselves—and in the meantime repay their owners with free labor for supporting them during their years as minors.

Rice remained bitter about his situation. He appears to have received the same purchase price from Stanton and Noyes, but he lost money because he was paid in Continental paper money that continued to depreciate in value. Moreover, he had to reimburse Beriah Brown £100 for the state’s expenses of maintaining Abigail and her children and pay the fees of his Stonington attorney.[26]

Both Stanton and Rice had to appear together to sign Stanton’s bond. Rice became enraged when Stanton again claimed that he had no role in Abigail’s escape. According to Rice, “with my naked hand I knocked him down and don’t know but believe I struck him again.” Stanton lodged a suit against Rice in the King’s County Court of Common Pleas, charging him with assault and seeking damages.[27] In a letter to the court, Rice defended himself. First, he claimed that the General Assembly had disgraced itself by taking away his “Negroes.” He even added some awful lines of poetry, including the following verses:

By a set of arbitrary knaves

I am deprived of lawful slaves

Rice concluded his letter by stating, “if the Honorable Court thinks I ought to pay anything for flogging a man of his character, I stand ready to do it, to the amount of any sum the Court pleases to inflict.” The defendant signed his name, “J. Rice, Infamous Carolinian.”[28] Apparently, Rice had to leave the state without being paid for Stanton’s purchase of Abigail and Milly.[29] Stanton apparently managed to keep the money frozen until the suit was resolved.

The court had the matter investigated by an impressive triumvirate: Henry Marchant, just back from serving as one of Rhode Island’s delegates to the Continental Congress; James Mitchell Varnum, a retired brigadier general of the Continental Army; and Freeman Perry of Charlestown. They recommended a verdict in Stanton’s favor, and the court agreed. The court ordered Rice to pay Stanton £30 in damages and for Rice to pay court costs of more than £50. Presumably, Sheriff Brown sent the remaining funds to the slave trader in North Carolina.[30]

Notes

[1] See Christian McBurney, “The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Aug. 1986), 81-93. [2] See William R. Staples, Annals of Providence: From Its First Settlement to the Organization of the City (Providence, RI: Privately Printed, 1843), pages 235-36; Mack Thompson, Moses Brown, Reluctant Reformer (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press,1962), 96-99. [3] General Assembly Resolution, June 1774 Session, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 7 (Providence, RI: A. C. Greene, 1862), 251-52. [4] Christian McBurney, “Freedom for African Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History, vol. 87, No. 276 (Summer/Fall 2017), 1-39. [5] Hartford, in Orange County in North Carolina, was also called Hart’s Mill and was near Hillsborough. For increasing antislavery activity, see Christian McBurney, “The First Efforts to Limit the African Slave Trade Arise in the American Revolution: Part 3 of 3, Congress Bans the African Slave Trade,” in the online Journal of the American Revolution (Sept. 15, 2020), at https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/09/the-first-efforts-to-limit-the-african-slave-trade-arise-in-the-american-revolution-part-3-of-3-congress-bans-the-african-slave-trade/. [6] John Penn Letter of Recommendation for John Rice, Nov. 27, 1779, Beriah Brown Papers, Mss 109, Box 4, Folder 7, Rhode Island Historical Society [hereafter “Beriah Brown Papers”]. Rice obtained a second letter of recommendation from officers of the North Carolina Brigade, then stationed in New York City. North Carolina Brigade Letter of Recommendation for John Rice, Oct. 22, 1779, in ibid. [7] See John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, Vol 8 (Providence: Cooke, Jackson Co., 1863), 5 (1776), 220 (1777), 389 (1778, and 563 (1779 (selection of Carder Hazard as justice and years); Caroline E. Robinson, The Hazard Family of Rhode Island (Boston: Privately Printed, 1895), 55-56. [8] Petition of John Rice of North Carolina to the General Assembly of the State of Rhode Island, Oct. 28, 1779, Rhode Island Petitions, vol. 17, fol. 118, Rhode Island State Archives (hereinafter, “John Rice Petition”). Most of the details of the episode involving John Rice and Abigail are from the prior source and Statement of John Rice to the Court of Common Pleas, King’s County, undated (probably late 1779 or early 1780), in the Beriah Brown Papers, infra (“John Rice Court Submission”). [9] For Carder Hazard’s enslaved men helping to unload HMS Syren, see Deposition of Martin Murphy, undated, William Davis Miller Papers, Mss 629, sub-group 12, box 2, folders 7 and Mss 673, series 4, sub-series C, box 3, folder 57, Rhode Island Historical Society; Christian McBurney, “’Strange Mismanagement’: The Capture of HMY Syren,” (April 10, 2014), in the online Journal of the American Revolution, at https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/strange-mismanagement-the-capture-of-hms-syren/. For Jacob Hazard, with Carder Hazard of South Kingstown as his owner, enlisting as recruit number 60, see An Account of the Negro Slaves Enlisted into the Continental Battalions, 1778, in General Treasurer’s Accounts Alphabetical Book, No. 6 (1761-1781), Rhode Island State Archives. [10] For Lodowick Stanton, see William A. Stanton, A Record, Genealogical, Biographical, Statistical, of Thomas Stanton, of His Descendants, 1635-1891 (Albany, NY: Munsell’s Sons, 1891), 426 and 432. Lodowick was married to Thankful in 1772. Ibid., 43. Stanton moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and died there in 1818. Ibid. He was reported to have a 150-acre farm on which he kept thirty cows. See Thomas W. Bicknell, The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Vol. 2 (New York, NY: American Historical Society, 1920), 482. For John Cross as a tin peddler from Westerly, see Joseph W. Blaine, ed., Nailer Tom’s Diary, A Preliminary Index (Newport, RI: Privately Printed, 1971), 51. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] General Assembly Resolutions, Aug. 1779 Session, in Bartlett, ed., Records of R. I., Vol. 8, p. 576; General Assembly Resolutions, Aug. 26, 1779, Rhode Island Resolves and Acts (“R.I. Acts”), Rhode Island State Archives, August 1779, p. 7. [14] See General Assembly Resolutions, Sept. 1779 Session, in Bartlett, ed., Records of R. I., Vol. 8, p. 586. [15] John Rice Court Submission, infra; John Rice Petition, infra. [16] Ibid. [17] R.I. Acts, October 1779, p. 6. Just the name of the act was set forth in the Bartlett edition. See Bartlett, ed., Records of R. I., Vol. 8, p. 618. [18] R.I. Acts, June 1790, p. 6. [19] Ibid., October 1779, p. 7. [20] Ibid. [21] See Lodowick Stanton Bond, December 13, 1779, and Joseph Noyes Bond, December 13, 1779, in Beriah Brown Papers, infra.; John Rice Petition, infra. [22] John R. Bartlett, ed., Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Taken by the Order of the General Assembly, in the Year 1774 (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), p. 153; Jay Mack Holbrook, ed., Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979), p. 118.; Bureau of the Census, Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Rhode Island (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908), p. 40; 1800 Federal Census, Charlestown, Rhode Island, National Archives. [23] Bartlett, ed., R.I. 1774 Census, 72; Holbrook, ed., R.I. 1782 Census, 89; Bureau of the Census, 1790 Census, Rhode Island, p. 50; 1800 Federal Census, Westerly, Rhode Island, National Archives. [24] Same bonds cited in note 20 above. [25] General Assembly Resolutions, February 1784 and October 1785 Sessions, in John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England, Vol 10 (Providence: Providence Press Co., 1865), pp. 7-8 and 132-33. For more on the emancipation legislation and the transition from slavery to freedom in Rhode Island, see Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery, Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England,1780-1860 (Cornell University Press, 1998), 66-69, 71-73, 76, 93-94, 98-103, and 206-08. [26] See John Rice Court Submission, infra; same source as in note 14 above. [27] John Rice Court Submission, infra. [28] Ibid. [29] Power of Attorney, Dec. 30, 1779, John Rice to Beriah Brown, Beriah Brown Papers, infra. In his instructions, Rice informed Sheriff Brown where he could send any money due to Rice if Rice was not able to collect it. [30] Court Record of Decisions, Court of Common Pleas, King’s County, February 1780 Session, p. 395 (Stanton v. Rice), Archives at the Judicial Records Center, Rhode Island.