After I published my book on the history of Kingston in 2004, a Narragansett Times reporter asked me who my favorite character in the book was. She expected me to say Elisha Gardner, the “Cat Inspector,” or Elisha R. Potter, Jr., the educated and refined leader of the village. But I chose Elizabeth Hagadorn for her defense of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party during the difficult years of the Civil War.

At the time, of course, women could not vote. But they could let their influence be known privately and publicly with the men who did vote. In her wonderful letters, one can feel Elizabeth Hagadorn’s strong and tangible support for the Union cause and the Republican Party. (Her letters are possessed by the Rhode Island Historical Society.)

Elizabeth (known as Lizzie) Wells was born on December 15, 1819, the daughter of Thomas Robinson Wells, for decades a cashier of the Kingston village bank and town clerk of South Kingstown. Her mother, Maria, had been born and raised in Kingston and was a cousin of Elisha R. Potter, Jr. All of their male children went to college, which was unusual for the day. Lizzie could not attend college, but she must have received an excellent education, based on her superb writing skills.

In June 1837, a number of Kingston villagers formed the Kingston Anti-Slavery Society. Seventeen-year-old Elizabeth became one of its first members, as did her brothers and sisters and step-mother.

In 1853, Elizabeth married Frank Hagadorn of New York. The Hagadorn family had roots in Kingston from the early 1800s. At the time of the Civil War, the couple were back in South Kingstown.

The Republican Party in the 1860 election opposed the extension of slavery in the South and voted in as president the party’s candidate, Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. The party then opposed the states in the South believing that they could secede from the Union. The Democratic Party in the 1860 election generally did not want to annoy the South by threatening the use of the power of the federal government to prevent the expansion of slavery. Many Democrats supported the Union cause but did not want the war to be cast as one for the abolition of slavery. Some Democrats even sympathized with the South. All of this played out in communities throughout Rhode Island, including in the small village of Kingston in the town of South Kingstown.

The Civil War broke out into open warfare when on April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked the United States military garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. The fort surrendered two days later. The news stunned the North, but also invigorated Northerners, leading them to begin forming regiments and engaging in military drills. The Northern states would not allow the South to secede without a fight.

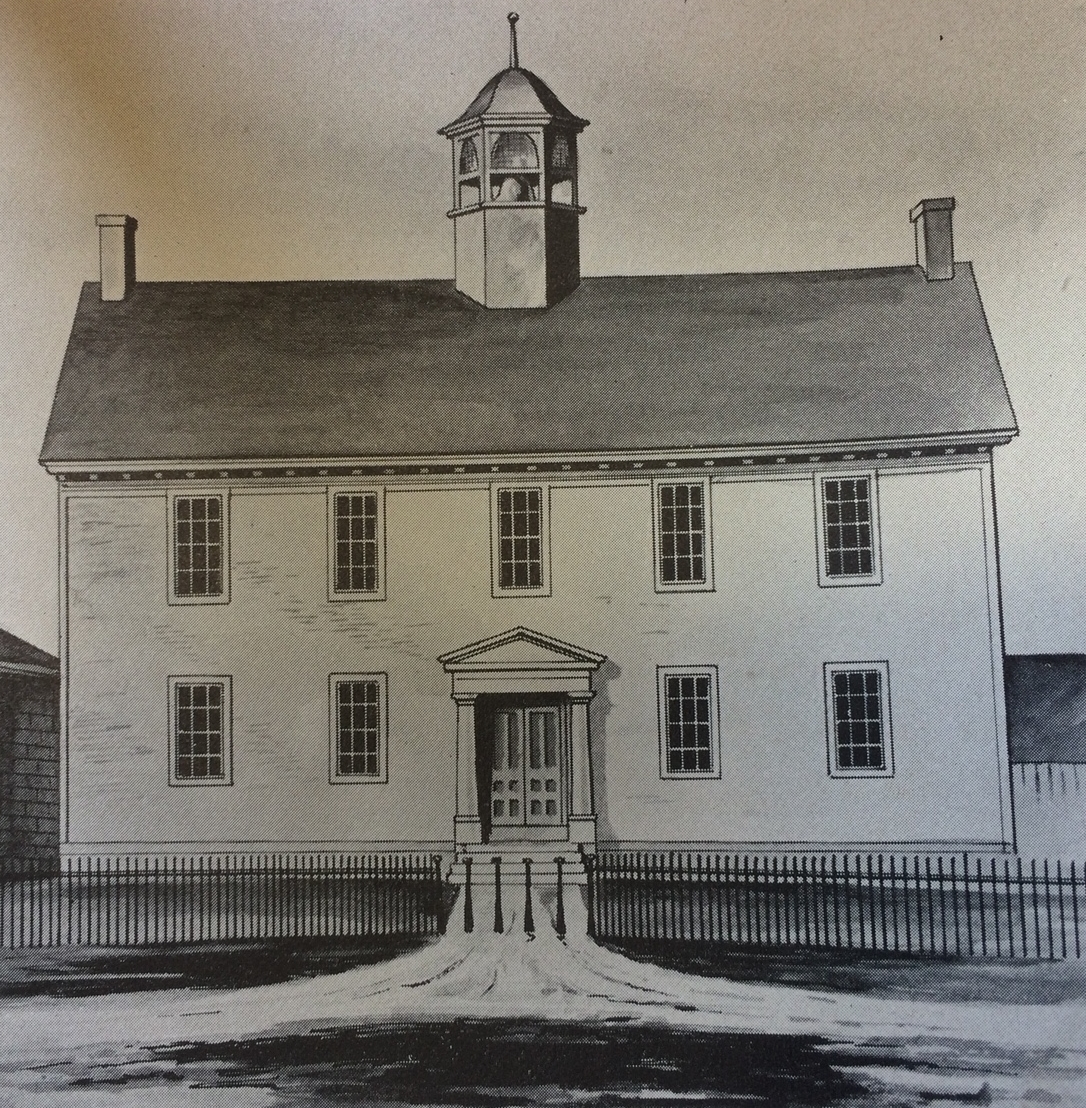

On May 4, 1861, at a meeting of the South Kingstown town meeting held at the Kingston Court House, town voters (all men) passed resolutions supporting newly-elected President Abraham Lincoln in the full conduct of the looming war. The town meeting pledged that the town would assist the families of the men who enlisted in the state regiments and would pay enlistees $1 for every six hours of drilling.

The Washington County Court House, by Henry Walling, 1857. Town meetings and musters of regiments during the lead up to the Civil War were held at the Kingston Court House, which served at the time as the Washington County Court House and South Kingstown Town Hall. The mansard roof that it currently has would not be added until 1876. (Christian McBurney collection)

Elisha Reynolds Potter, Jr. moderated the town meeting. Potter resided at the Potter Homestead in Kingston, built in 1809 (where I grew up). Well educated and refined, he was the village’s most prominent individual and a seasoned state politician. During the turbulent years of the Dorr Rebellion, Potter had helped to found the Law and Order Party and represented Rhode Island’s rural interests in generally opposing the expansion of the right to vote to working but landless urban immigrants (mostly Irish) in Providence and other cities. Potter helped to maintain an unfair system that allowed rural Rhode Islanders to have an outsized influence on the politics of the state, despite their proportionally small population. Potter had even been elected in 1843 for a term, under the banner of the Law and Order Party, as Rhode Island’s representative in the U.S. Congress. Eventually, the Law and Order Party disbanded and Potter returned to the Democratic Party.

South Kingstown’s greatest military hero during the Civil War would be Isaac Peace Rodman. He was co-owner and operator with his father, Samuel Rodman, and brother, of five textile mills, most of them in the Rocky Brook neighborhood of Peace Dale. He also served as the president of the Wakefield Bank, and he had served several years as president of the town council and a representative in the General Assembly. When the Civil War broke out, he was serving his second term in the state senate. He was a close friend of Governor William Sprague, a Democrat who was a strong supporter of the Union cause.

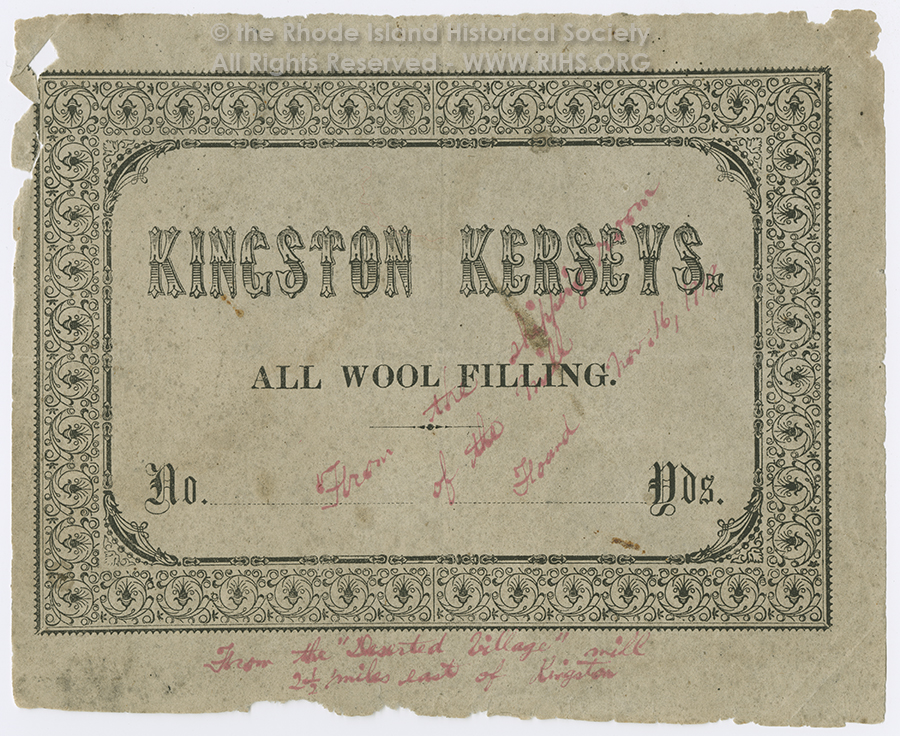

Rodman organized an independent company, settling on the name Narragansett Guards. On April 19, 1861, a meeting of the outfit was held at Kingston Court House. Prior to the meeting, 94 men, mostly hailing from Wakefield, Peace Dale and Rocky Brook, assembled in Peace Dale and marched to Kingston to attend the meeting. After an hour of drilling, the company was dismissed and the men were requested to meet for drill every evening. Many of the recruits worked in Rodman’s mills that had made “negro cloth,” which was made into clothing for enslaved people in the South. The war ended this business and the mills closed. The mill workers, many of them Irish immigrants, and Rodman patriotically supported the Union cause.

Fabric label. Kingston Kersey All Wool Filling, no date, Ephemera Collection, Box 4, Rhode Island Historical Society. RHi X17 2824. The mill that made the label was probably at Mooresfield, about 2 1/2 miles east of Kingston. Kersey would have been produced also at the nearby Rodman Mills at Rocky Brook and was used to clothe enslaved people in the South (This image has a Rhode Island Historical Society watermark and may not be used without its permission).

With a total of 130 men, the Narragansett Guards were organized as Company E of the 2nd Rode Island Volunteers, known as “South Kingstown’s Own.” The soldiers voted for Isaac Rodman as their captain, and Governor Sprague confirmed the appointment.

On June 2, 1861, orders were issued requiring Company E to depart from the Kingston railroad station (then called Kingston Depot, in what is now West Kingston) for Providence on the afternoon of June 4. After being supplied and trained, on June 19 Company E would then take a steamer from Fox Point in Providence for New York City and travel by train for the rest of the journey towards Washington, D.C. to help defend the Union capital.

Thomas Potter Wells, the brother of Elizabeth and a staunch Union supporter, and the cashier of the village bank, and his third wife Julia (Johnson) Wells, offered to host a farewell party for the soldiers on the spacious lawn between their home and the Kingston Congregational Church, which stood across from the Court House. The offer was accepted. Thomas’s sister, Elizabeth, who got along well with Julia, must have helped to organize the party.

Portrait of Isaac Peace Rodman by James Lincoln. Rodman was the first New England Union general to be killed in the Civil War (Brown University Portrait Collection)

On June 4, Captain Rodman marched Company E to Kingston, where he and his men leisurely gathered on the lawns of Kingston’s houses on the main street, drinking punch and eating food brought to them by villagers. It must have been an idyllic scene in the small village, with flowers and grass providing a carpet and ancient tall elm trees providing the shade. Music filled the air, and women had one last dance with their beaus. Reassuring speeches were given. Captain Rodman then announced it was time for the soldiers to depart for the train. Wakefield’s new newspaper, the Narragansett Times, reported on the memorable and heart-wrenching scenes:

About 3 o’clock the volunteers formed in front of the Court House, and escorted by the Home Guards marched to the depot. A long train of vehicles proceeded and followed the companies., and the roads were thronged with people on foot. The procession occupied the whole slope of Kingston Hill extending nearly half a mile. Good judges estimated two thousand persons were the station. There were many women and children who had come to say farewell to their husbands, fathers and brothers. There were many parents, past the prime of life, who had come to bid their sons Godspeed. There were many moist eyes and quivering lips, but the moist eyes and quivering lips bespoke an emotion which did honor to the heart beating beneath.

Elizabeth’s letters make it clear that not everyone in Kingston village or South Kingstown enthusiastically supported Union war efforts, especially early on. South Kingstown was a strong Democratic town, and some Democrats, including one of Elisha R. Potter, Jr.’s brothers, were angry that Republicans had, in their view, goaded the South into war.

Elizabeth wrote often to her half-brother, Amos Palmer Wells.He had enlisted as a captain in the 11th Regiment of New York Volunteers in May 1861. In 1861, Elizabeth caustically commented to him on the lukewarm war support in South Kingstown. Elizabeth proudly noted that the Company E soldiers were mostly “operators in the factories and mechanics — some of whom were foreigners.” These “foreigners” would have been Irish and other immigrants. By contrast, she noted, there “was not a farmer in the company.” Most adult men in South Kingstown were farmers of English stock. Her comment indicates that most of the town’s farmers were rural Democrats who initially did not strongly support Union war efforts.

The Union loss at the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, shocked northerners and helped to galvanize their support for the war. Rhode Island regiments took an active part in the battle. Hagadorn achingly wrote of her acquaintances and townsmen who had been killed in the battle. In the case of one soldier from Company E who had died, Hagadorn recalled that she had seen the soldier’s mother on the day Company E departed Kingston “in a flood of tears.” Hagadorn noted that the Battle of Bull Run had “wrought quite a change in the minds of some of our secessionists here — Elisha Clarke says now, he is ready to go and fight with all his might. Even John Larkin says he is ready to fight for law and government.”

Divisions in the village broke out in the open when James B. M. Potter sought a position in the Union army, while at the same time publicly criticizing the Union cause. The younger brother of Elisha R. Potter, Jr., James had owned and operated textile mills at South Ferry and Usquepaug. Potter suffered, however, “heavy losses on his goods” for several years and in February 1861 was forced to turn over his two mills and his interest in the South Ferry mill to a bank at Kingston. At the age of 43, he had to find a new career. With the coming of the Civil War, he decided to seek a post as paymaster with the Union army. Elisha R. Potter, Jr., a close ally of Democratic Governor William Sprague, persuaded Governor Sprague to write a letter of recommendation for James to bring to Washington, D.C. But before he departed, James, a die-hard Democrat, shocked Kingston villagers with his anti-Union statements.

Elizabeth Hagadorn angrily wrote in a July 29, 1861, letter to Amos that Potter’s “last wishes, before leaving home, were strongly expressed for the success of the rebels and denouncing the [Lincoln] administration in the severest language possible.” This conduct was particularly hurtful to many villagers, as they had recently heard the news of the Union loss at the Battle of Bull Run. Hagadorn wrote that before July 4, someone had sent a letter to the proper authorities in Washington, D.C. alerting them to Potter’s sentiments. The rumor was that villager John G. Clarke, Jr. had sent the missive. Clarke denied it to Hagadorn, but said that he “felt sufficiently indignant to do so.” Hagadorn concluded about James Potter, bitterly, “I think we are in more danger from such traitors in the Cause than from the rebels.” Potter ended up securing the job.

While Elisha R. Potter, Jr. was not a military man, he played an important role in Rhode Island’s legislature. In some ways consistent with President Lincoln in the early years of his administration, Potter emphasized bringing the South back to the Union instead of insisting on the defeat of the South and eliminating slavery. As a member of the Rhode Island senate at a special session on August 10, 1861, Potter introduced a resolution calling for the “full and sincere union of all political parties.” While he spoke about the hope of restoring peace and the Union, he was enough of a realist to recognize that that was unlikely to occur and was remarkably prescient to recognize that Union goals in the war could change. At this early time in the war, most Union soldiers fought to preserve the union of the states. They did not want to see the country forged in the American Revolutionary War as an experiment in democracy become split into numerous countries and become like Europe, constantly fighting. Potter pledged the “entire resources” of the state “for the preservation of the Union.” In his speech, Potter argued that the resources of the South, and the reasons that had led it to secession, were such that the North must expect a difficult war. Speaking only a few weeks after the Union’s loss at the first Battle of Bull Run, Potter expected that the war would be a “bloody one.” He noted, “compromise is for the present out of the question. Since the last battle, the South will not, and the North cannot with self-respect, offer terms of peaceable re-union.” Yet Potter saw that the vision of why Union soldiers fought would eventually be transformed. He stated that “it seems to me” that “we are inevitably drifting” into “an anti-slavery war.” Potter also expressed disbelief that the South would resort to a war which would have as its likely end result the destruction of the institution of slavery that the South sought so earnestly to protect. The Narragansett Times reprinted Potter’s entire speech on its front page.

Potter, to his credit, sponsored a bill in the state senate to give equal voting rights to naturalized citizens who fought in the Union forces. This would have included many Irish male immigrants who had been excluded from the voting rolls under the 1843 state constitution that Potter helped to draft. Wilkins Updike, a prominent attorney and politician also residing in Kingston, however, helped to block the measure, which led to his being the target of a vitriolic attack in a Providence newspaper. At a South Kingstown town meeting held in June 1862, with Wilkins Updike serving as moderator, town voters instructed their representatives to oppose legislation that would extend voting rights to native born citizens who did not otherwise satisfy legal requirements, on the ground that “no person ought to be allowed to vote in questions of taxation unless he is himself taxed.” Even the risk of soldiers dying in combat did not change their views.

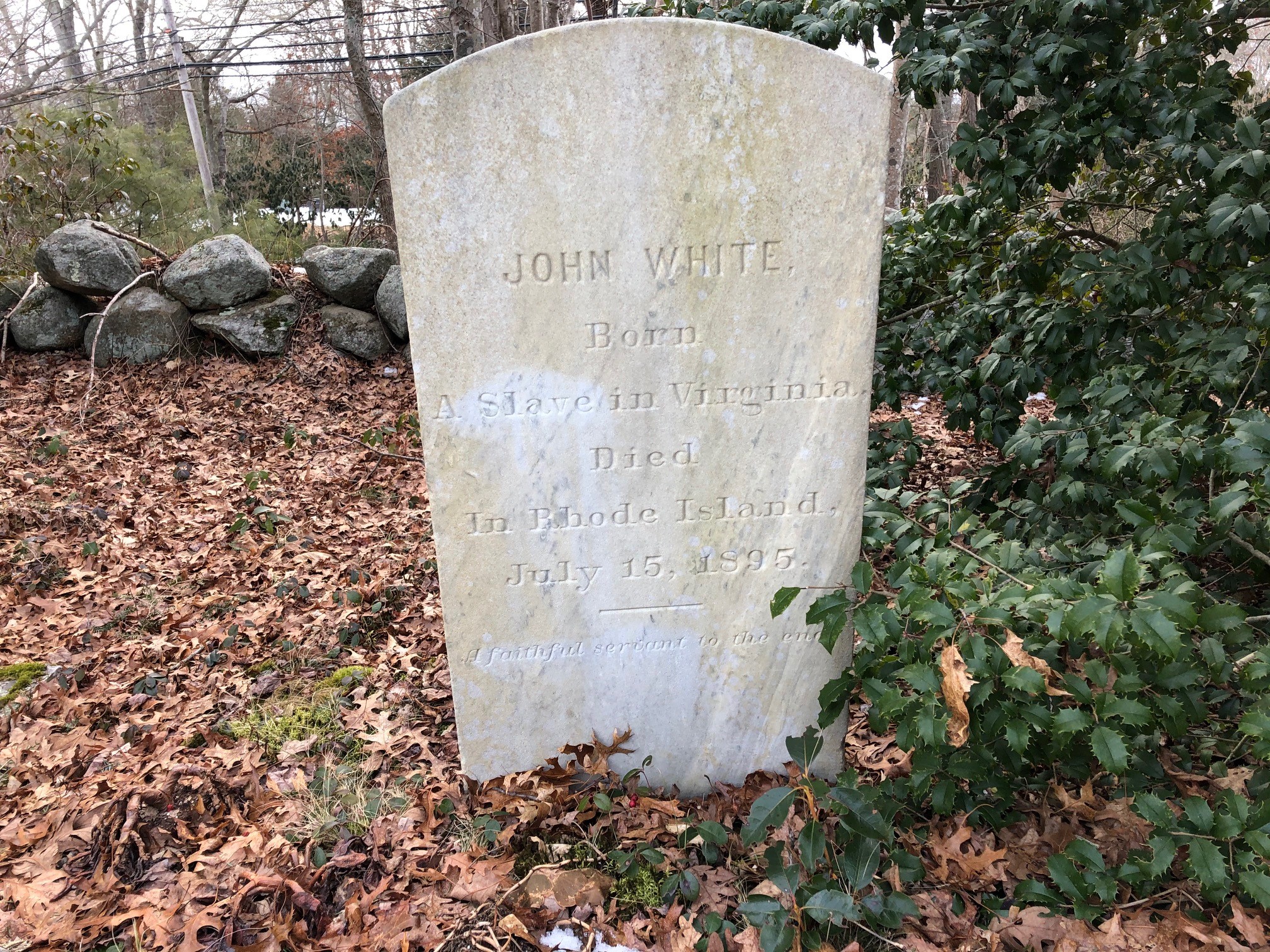

Potter also pushed forward a state senate investigation as to whether an amendment to the state constitution was “necessary to prevent slaves who have escaped, or who may escape, from the Southern States into this State, from voting without proper restrictions.” Potter was supported in this effort by Thomas P. Wells, an abolitionist. Both men were concerned that enslaved people, lacking in education and experience being free, would not be informed voters. Perhaps Rhode Island’s experience with the Dorr Rebellion led them to focus on this odd issue. (One former Virginia slave, John White, did settle in Kingston, where he died in 1895.)

Gravestone for John White, “Born a Slave in Virginia, Died in Rhode Island, July 15, 1895, A Faithful Servant to the End.” Old Fernwood Cemetery, Kingston (Christian McBurney)

The bloody war continued and many townsmen who had enlisted in Rhode Island regiments were killed in combat or by disease. Isaac Peace Rodman (who will get his own article one day) thrived as an officer, and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. Tragically, on September 17, 1862, he was killed by a cannonball late in the battle of Antietam in Maryland, the deadliest single day in the history of American warfare. Rodman’s body was brought by train to Kingston Depot and then by horse-drawn funeral coach through Kingston to his stone home in Peace Dale (which still stands) at the corner of Kingstown and Saugatucket Roads. The procession of mourners extended for two miles. This occasion was in sad contrast to the higher hopes the townspeople had felt on June 4, 1861, when the officers and men of Company E had stood in front on the Court House in front of hundreds of their townspeople before departing for the war.

As the war dragged on, and thousands of more Union soldiers were killed or suffered horrible wounds in battles, and with no end to the war in sight, sentiment against the war increased in the North. This was particularly true in Democratic strongholds, such as rural South Kingstown. The appearance of Internal Revenue Service agents at the John N. Taylor tavern in Kingston to collect federal taxes (newly imposed to support the war effort) from local townsmen added to the anger of Democrats.

In March 1863, Elisha R. Potter, Jr., still a leading Democrat, created a controversy, as a result of his relatively sympathetic view of the South. In the state senate, he introduced a resolution calling for the “settlement of our present national difficulties upon the basis of a restoration of the constitutional rights of all the States, as soon as it can honorably be done.” Potter was calling for an end to the war and a return to the status quo permitting slavery. To the credit of the state senate, the resolution failed to pass. For most Rhode Islanders, as Potter had feared in 1861, the war had gone too far merely to return to the status quo on the slavery issue.

Anti-war sentiment reached its pinnacle during the 1864 presidential election. As Confederate leaders understood, they did not have to win the war to secure their independence; all they had to do was to exhaust the male voters in the North and influence them to vote out Lincoln’s war administration. In the lead up to the upcoming election, General Lee had stymied General Grant’s march on Richmond by digging in at Petersburg, and General Sherman was halted outside Atlanta. Prospects for a second term for Lincoln looked bleak. Finally, Sherman presented a present to Lincoln by forcing the Confederates to evacuate Atlanta on September 1.

In October 1864, at a crowded meeting of South Kingstown Democrats in the Kingston Court House, Elisha Potter delivered a speech in favor of General George McClellan, President Lincoln’s Democratic opponent. McClellan had led the Union army in the East early in the war and became popular with Union soldiers but had been rightfully sacked by Lincoln for incompetence. In the election, McClellan hinted that he wanted to end the war, which, if he had succeeded, would have left slavery in place in the South for the four million enslaved people there.

In response, on November 4, 1864, a large crowd of Republicans met at the Kingston Court House in support of Lincoln for President. Peace Dale’s Rowland Hazard, South County’s richest mill owner, inveighed against the “Peace Party” and asked the crowd whether it wanted to “succumb to the South and give up all that we have conquered from it.”

Women were prominent at both gatherings. They could not vote, but they made sure they were seen and heard.

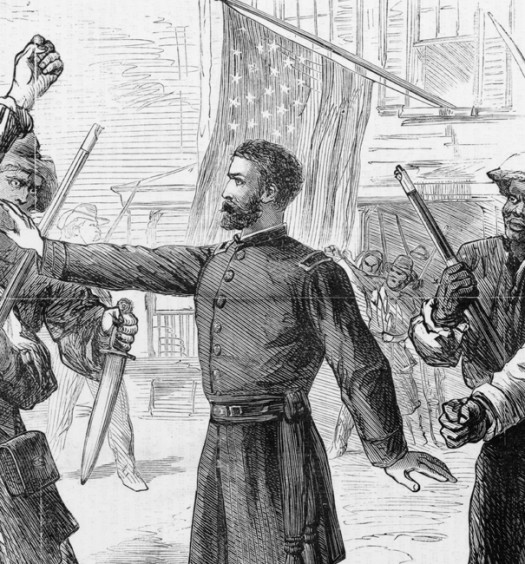

Elizabeth Hagadorn, a strong Republican supporter, wrote about the election to her brother, Amos. He had become a major in the 20th New York Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops, which was raised in New York City in March 1863. His service must have made his abolitionist father and sisters proud. In her letters, including to her husband Frank, Elizabeth called the Democrats “Copperheads,” a derogatory term for Northerners who wanted to end the war immediately. She glumly expected that a majority of town voters would support McClellan. On election day, Hagadorn wrote with disgust that there were Democratic leaflets plastered on the village’s trees and in the Court House, where the town voters cast their votes. (Under current law, leaflets supporting a candidate at a voting place is not allowed.) The leaflets claimed that a second Lincoln administration would increase prices and taxes

To Hagadorn’s great pleasure, a majority of South Kingstown voters voted for Lincoln—but by a margin of just 26 votes. The staunch Republican wrote that while she was “ashamed that I live in a town that could give so small a majority against traitors, and rebels, I rejoice that the town has not been blackened by giving her votes in favor of them.” Hagadorn was pleased to take note of the increasing popularity of the Republican Party “in our Coppery town.” Overall, Lincoln won Rhode Island easily by a margin of 62% to 38%.

Finally, in early April 1865, Confederate armies began surrendering. America’s most deadly war was over. No surviving letter exists revealing Elizabeth Hagadorn’s thrill of sharing in the glow of victory and the end of slavery in the South, but no doubt she felt it.

But then, tragically, Lincoln, who had steadfastly guided the Union to victory, was assassinated on April 15 at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Ironically, none other than James B. M. Potter was a witness. After serving in the Union army, his harsh anti-Lincoln sentiments must have changed. In 1864 he was promoted to major and paymaster and in 1865 the U.S. Senate conferred on him the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel for faithful and meritorious service during the war. Newspapers had advertised that Lincoln and Grant would attend that evening’s performance at Ford’s Theater and Potter decided he wanted to attend. He had a good view of the President and his wife, Mary, in their upper-tier box close to the stage. Suddenly, he heard the crack of a pistol and saw a man jump from the President’s box. Potter yelled that the President had been shot and he urged his friend Dr. Morely to attend to him. Potter was asked to assist in escorting Mary Lincoln across the street to the Peterson boarding house where a grievously wounded President Lincoln had been taken. Potter recalled Mary exclaiming, “Oh, why did they let him do it?” Potter said he also attended to Major Henry Rathbone, who had been in the box with the Lincolns and had been stabbed with a knife by the assassin. Potter wrote these recollections in a letter in 1890 to John Hay and John Nicolay, Lincoln’s secretaries; but his letter came after they had published their ten-volume biography of the fallen leader.

Elizabeth must have grieved deeply upon learning of the death of Lincoln. Her spirits must have lifted upon hearing that her brother Amos had mustered out of the army. But the war had more pain in store for her. Amos had served as a major in the 20th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, in 1864 and 1865, mostly in Louisiana and Texas. But he contracted tuberculosis in the military service and died of it on January 27, 1866. He left behind him at Glens Falls, New York, his wife of four years, Emma, and a six-year-old son and two-year-old daughter.

Notes

This article is based mostly on the chapter “Kingston during the Civil War” in Christian M. McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004).

For information on Elizabeth (Wells) Hagadorn, Thomas R. Wells, and their family, see Representative Men and Old Families of Rhode Island (Chicago, J. H. Beers & Co., 1908), v. 2, p. 1033; Guide to the Hagadorn-Wells Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society, https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/Mss629-10.htm. For the list of the members of the Kingston Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, see McBurney, History of Kingston, appendix C.

For Isaac P. Rodman and the formation of the new regiment, see John Bartlett, Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers in the Civil War, 357-62; Oliver H. Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane (West Kingston, RI: Kingston Press, 1999), v. I, 184-89. For the town meeting on payment for enlistment, see South Kingstown Town Meeting Records, v. 2, 229-30 (May 4, 1861). For the farewell hosted by the Wells, see Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane, v. I, 184-89; Narragansett Times, June 7, 1862, 2. For Rodman’s Civil War experiences, see Bartlett, (ed.), Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers in the Civil War (Providence: Sidney S. Rider & Brother, 1867), 357-62; J. R. Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties (New York: W. W. Preston, 1889), 529-30. For Rodman’s first return to South Kingstown, see id.; Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane, v. I, 184-89; Letter from Elizabeth (Rhodes) Robinson, dated July 9, 1862, Hagadorn-Wells Papers, MSS 629 SG 10, Box 2, Folder 1, Rhode Island Historical Society. (Elizabeth Robinson was the step-mother of Elizabeth Hagadorn).

For Potter’s Senate speech, see Elisha R. Potter, Jr., Speech of Hon. Elisha R. Potter, of South Kingstown, upon the Resolution in Support of the Union (Providence: Cooke & Danielson, 1861) 2-11; Narragansett Times, Aug. 31, 1861, p.1. For Potter’s efforts to extend the vote to Irish-American soldiers, see Patrick T. Conley, An Album of Rhode Island History, 1636-1986 (Norfolk, VA: Donning Co., 1986), 107. For the town meeting against extending the vote to native born citizens, see South Kingstown Town Meeting Records, v. 3, 38-39 (June 7, 1862. For reference to the attack on Updike, see Narragansett Times, Sept. 19, 1862, 2. For Potter’s resolution on freed slaves from the South voting in Rhode Island, see Narragansett Times, Feb. 13, 1863, 2. For federal taxes, see Narragansett Times. Sept. 25, 1863. For Potter’s 1863 resolution, see Elisha R., Potter, Jr., Speech of Hon. Elisha R. Potter of South Kingstown, March 14, 1863 (Providence: Cooke, Jackson & Co., 1863), 20-23 & 29-35. For the pro-McClellan meeting, see Narragansett Times, Oct. 28, 1864, p. 2, c. 2.

For the pro-Lincoln meeting and Presidential election vote in Kingston, see Narragansett Times, Nov. 4, 1864, p. 2, c. 2; letter from Elizabeth (Wells) Hagadorn to Frank Hagadorn, dated Nov. 11, 1864, Hagadorn-Wells Papers, Mss 629, SG 10, Box 2, Folder 2, Rhode Island Historical Society. For James B. M. Potter, see McBurney, A History of Kingston, chapters on Elisha Potter; Efforts at Manufacturing in Kingston Fail; and The Potter Brothers, Updike and the Aftermath of the Dorr Rebellion; see also Narragansett Times, Feb. 15, 1861 (involuntary assignment of mills); letter from Elizabeth (Wells) Hagadorn to Amos Wells, dated July 29, 1861, Hagadorn-Wells Papers, Mss 629 SG 10, Box 2, Folder 6, Rhode Island Historical Society; James B. M. Potter, “Recollections of a Paymaster of the Army During the Civil War” (1896), James Brown Mason Potter Papers, Mss 629 SG 6, Box 1, Folder 7 (appointment as paymaster and service in Union army; he retired from the U.S. Army in 1882).

For James B. M. Potter’s letter regarding President Lincoln’s assassination, see letter of James B. M. Potter to J. G. Nicolay and John Hay, Jan. 7, 1890, John Hay Correspondence, 1854-1914, “Platt” to “Ray,” John Hay Library, Brown University.

For US Army records on Amos Palmer Wells’s military service and death, see www.fold3.com (search in Civil War—Union Army for “Amos P. Wells”).