One of my favorite hobbies is reading popular and top quality American history books by authors who have deservedly built national reputations. By popular history, I mean the author is neither a college professor nor holds a Ph.D. in history. Remarkably, four Brown University undergraduate alumni who graduated in a five-year period from Brown are at the top of these ranks: Nathaniel Philbrick ’78, Eric Jay Dolin ’83, Edward Ball ’82, and Tony Horwitz ’80.

Recently, I walked into an independent bookstore in the small but charming town of Shepherdstown, West Virginia. I was not surprised to see books offered on its shelves from each of these talented Brown historians.

A common feature that each of these national best-selling authors have is that their books combine excellent and accurate history with being eminently readable. Their books typically have the narrative flow of a fine novel.

Another feature at least two of the authors share is that they were blessed with a spouse who supported them financially while the struggling author tried to make a go of earning a living as a history writer. Based on my own meager book royalties, I stand in awe of those who can earn a decent living writing history books.

Nathaniel Philbrick broke out in 2000 with his short book, In the Heart of the Sea, The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, the winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction. The book tells the two true stories of a sperm whale that slammed into a Nantucket whaleship (the basis for Herman Melville’s Moby Dick) and an incredible survival story. Meanwhile, readers concisely learn about those extraordinary Nantucket whalers.

Another notable Philbrick book is Mayflower, A Story of Courage, Community, and War. This book combines the remarkable settlement of Plymouth, Massachusetts, by the Pilgrims and the tragedy of King Phillip’s War, which ended the power of southern New England Indian tribes. As The Hartford Courant wrote of the book, Philbrick “illuminates the conflicts and fleshes out the stick-figure characters we were all fed in Propaganda 101.”

My neighborhood men’s book club loved In the Heart of the Sea, and my wife’s women’s book club lauded Mayflower.

Recently, Philbrick has written a fine trilogy on the American Revolutionary War. My favorite is the first one, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution, which focuses on the overlooked radical Patriot Dr. Joseph Warren.

Growing up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Philbrick somehow developed a passion for sailing. By attending Brown University, he was in sight of Narragansett Bay, where he became Brown’s first Intercollegiate All-American sailor in his senior year in 1978, the same year he won the Sunfish North Americans at Barrington, Rhode Island. In the class room, he majored in English, not history.

When I asked Philbrick what Brown did best to prepare him for a writing career, he responded, “It was in Professor George Monteiro’s Honors Short Story and Poetry classes that I learned to write. He required a 2-page paper every week, and as any writer knows writing short is much harder than writing long.”

After graduating, Philbrick earned a master’s degree in American Literature from Duke University. He worked as an editor of a sailing publications before developing the history writing bug. Philbrick moved to Nantucket in 1986 and has remained there ever since, with his wife Melissa. In his latest book, Travels with George, In Search of Washington’s Legacy, Philbrick follows the journeys of the country’s first President, George Washington, on his travels north (including to Newport and Providence) and south. Philbrick includes in his narrative his own retracing of Washington’s trips, which he did with Melissa and their lively dog, Dora.

Eric Jay Dolin has made a specialty of selecting broad topics and writing entertaining narratives about them. My favorite book of his is his first effort for a national audience in 2007, Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America. He followed that one with the fascinating, coast-to-coast story of Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America.

Dolin’s best-seller is about pirates. As with his other books, the title tells it all: Black Flags, Blue Waters: The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious Pirates. Another popular book, particularly in New England, has been A Furious Sky: The Five-Hundred-Year History of America’s Hurricanes, published in 2020.

Dolin’s most recent book is the forthcoming Rebels at Sea: Privateering in the American Revolution. This book is on a topic—privateering—that my latest book focuses on as well; Dolin’s is the best survey on this underrated topic. I also had the privilege of reading a manuscript of it and giving my comments to Eric.

After growing up near the coasts of New York and Connecticut, Dolin came to Brown wanting to become a marine biologist—more specifically, a malacologist (seashell scientist). In fact, Brown Alumni Monthly even published an article during his freshman year titled, “The Admission’s Office Called him ‘Shell-Man.’”

After earning a double major in biology and environmental studies, Dolin realized he did not want to spend his working life in laboratories. He obtained a master’s degree in environmental management from Yale University and a Ph.D. in environmental policy and planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

While working in a variety of jobs in the environmental policy field, Dolin penned several books and numerous articles. Eventually, he realized that he wanted to become a professional writer—writing about American history. He has succeeded marvelously, with his books benefitting from his background in maritime and natural history. Dolin credits Brown with helping him along that path. He said in an email to me that “Brown, by the nature of its curriculum and philosophy, encouraged me to be curious and pursue my passion, and both in classes, and by writing occasional op-eds for the Brown Daily Herald, the Brown Banner, and other campus publications, I honed my writing skills.” Today, Dolin lives with his wife, Jennifer, in Marblehead, Massachusetts.

Edward Ball exploded onto the history-writing scene with his Slaves in the Family¸ which follows generations of his White ancestors, one of whom moved onto a plantation outside Charlestown, South Carolina, in 1698. Ball family ancestors built a dynasty lasting six generations, acquiring more than twenty plantations. The book is also about the enslaved people forced to work on the plantations. Ball traces the ancestry of one enslaved family line for ten generations. Ball was quoted in a 2007 article in Brown Alumni Magazine about his book, “I wanted to bring the stories of slaves up out of obscurity and bring the stories of white people down so they were on the same level. . . . . Acknowledging the fact that my family took part in some of the worst episodes of American life instead of running away [from that fact] – I hope it’s the honorable thing to do.””

I recently purchased from a Nantucket independent bookstore Slaves in the Family (which stood in front of Dolin’s book on Hurricanes) and reread it. Despite the considerable studies of slavery that his book helped to spur over the last two decades, I found that Ball’s book as a history stands the test of time.

Ball has continued to write history books, most recently, in 2020, Life of a Klansman, A Family History in White Supremacy. This book is a about another Ball ancestor. Ball was quoted in a 2020 article in Brown Alumni Magazine that his book attests that “this happened, this is not only my family, but part of our national history—and not an uncommon part. The story is that white supremacy is deep in American life, it is long lived, and it is normal.”

After growing up in Charleston, with the help of student loans and financial aid, Ball attended Brown, where he studied semiotics and history. After graduation, he became a freelance journalist in New York City.

Tony Horwitz had a brilliant career in journalism, including winning the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 1995, before turning to writing best-selling books. In his books, he combines both history and his own travels, creating his own genre.

Horwitz gained fame with his 1998 book, Confederates in the Attic, Dispatches From the Unfinished Civil War. To write the book, he embedded himself on weekends with Civil War reenactors. The Confederacy, he found, was alive and well, and as full of animus at the idea of equality and tolerance as ever. Horwitz once asked a Klanswoman and grandmother why she was not wearing her Klan robe. “It’s a good look,” she said, but “the cleaning bills will kill you.”

In Horwitz’s two most recent books, he returned to studying the Civil War, this time its origins, as well as our country’s social and political divide today. He looked beyond the myth to find the character of abolitionist John Brown for Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. In Spying on the South, An Odyssey Across the American Divide, published in 2019, he retraced the journey of Frederick Law Olmsted, who before he designed New York City’s Central Park, wrote dispatches for The New York Times while traveling in the pre-Civil War South.

Horwitz was raised in Washington D.C. and graduated from Brown with a degree in history in 1980. (Horwitz returned to Brown as a fellow of the John Carter Brown Library in 2007). He then obtained a master’s degree from the Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

In 2006, Horwitz moved to West Tisbury, Martha’s Vineyard, with his wife, Geraldine Brooks, a noted journalist and a marvelous historical novelist. Tragically, he died suddenly in May 2019, apparently of cardiac arrest. “His journalism was always participatory, and he took readers along for the ride,” Joel Achenbach, a reporter for The Washington Post, said in an email to The New York Times the day after Horwitz’s death. “He climbed masts on sailing ships, rode mules, marched with Confederate re-enactors, and ventured into dive bars in the remote crossroads of America.”

My own time at Brown as an undergraduate (class of 1981) overlapped with each of Philbrick, Dolin, Ball and Horwitz. But, regrettably, despite majoring in history, I do not recall meeting any of them in my four years at Providence. I have had the pleasure of meeting Philbrick and Dolin recently.

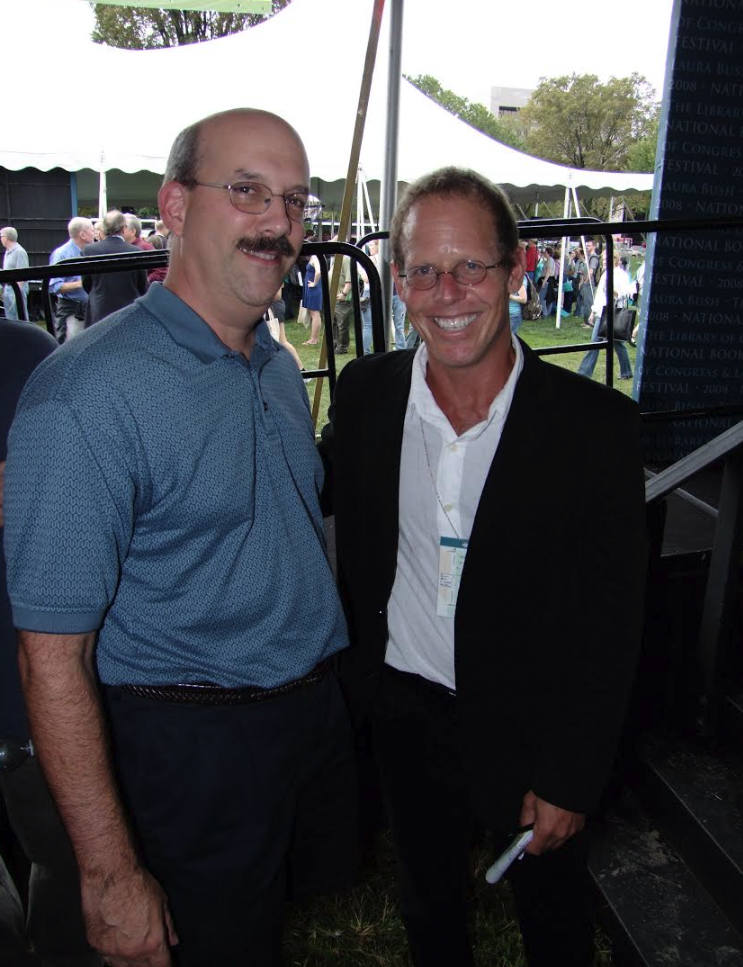

I did briefly meet Tony Horwitz. I attended every National Book Festival in Washington, D.C., when it was held on the grassy ground of the National Mall. I would always sit in the second row, in front of the speaker—it was as close to heaven as I thought I would ever get. In 2008 Horwitz came to speak about his latest book. I must have informed a photographer, Bruce Guthrie, hanging about that I had attended Brown the same time Horwitz had. After Horwitz stepped down from the speaking podium, the photographer pushed us together and quickly snapped our photograph. As the photograph was taken, Horwitz muttered, “I don’t even know this guy.” It was true, but I am glad it happened.

Tony Horwitz and Christian McBurney at the National Book Festival in 2002 (by, and courtesy of, Bruce Guthrie).

I hope I have made a convincing case that an impressive array of talented popular historians with national reputations writing books on American history once walked the grounds of Brown’s campus as undergraduates in a five-year timespan. I suspect that few, if any, universities or colleges, can make the same claim.

I encourage you to consider reading the books mentioned above, and the many others that were not mentioned in this article.