The article prominently mentions three Rhode Island locations: Block Island, Newport and Providence. Chamberlin mentions how Newport residents expected to see a naval battle off their cliffs between recently-armed rumrunners and Gray Ghost. Chamberlin also wonderfully describes the insular community on Block Island that protected rumrunners from outsiders (including, as here, New York World newspaper reporters posing as buyers of bootleg whiskey). The newspaperman further colorfully describes how a customer seeking offshore bootleg whiskey places an order to “financial” agents stationed in a room in a large Providence hotel.

Chamberlin’s article, selected as on the best news stories of 1923,[1] is so well written and provides such a great sense of the times that it is set forth in its entirety below.

This article is being released in conjunction with the publication of my new book: Christian McBurney, Machine Guns in Narragansett Bay: The Coast Guard’s War on Rumrunners (History Press, 2023).]

“Rumrunner Linwood is set afire by her crew in an attempt to destroy evidence before seizure by a pursuing U.S. Coast Guard patrol boat, May 1923” (National Archives)

Out in the Atlantic Ocean, ten miles beyond the three-mile limit and between Block Island, off the Rhode Island coast at the extremity of Long Island Sound, and Nomans Land, there has been lying for the last three weeks a liquor-bearing armada of fourteen or sixteen vessels which has been flooding New York and New England with 20,000 cases of liquor weekly.

More than half the vessels in this fleet are part of the international system of two rival New York syndicates. Both of these organizations ship their liquor directly from England and Scotland in tramp steamships to St. Pierre, Miquelon. Here it is transshipped to three-masted Gloucester fishing smacks, carrying 2,000 cases each, which make up the armada off Block Island.

These schooners are operated by a skipper and crews of nine or ten deep-sea fishermen, strong, hardy and courageous. They are all armed with automatic pistols and sawed-off shotguns, although an ordinary strong man, even armed with a club, would hesitate to attack one of these fishermen who had only his bare fists for defense.

The one thing these men fear and in which apparently is the one hope of ending rum-running on this coast, is a liquor pirate nicknamed the Gray Ghost. This ship, a big steel trawler painted a battleship gray, is armed with a one-pounder in her bow and carries machine guns aft on both starboard and port.

The crew consists of sixty as reckless ruffians as ever sailed with Capt. Kidd. As the Gray Ghost, looming out of a fog like an apparition, appears suddenly alongside a schooner at night, these men board their prey with pistols in their hands instead of cutlasses. Almost before the schooner’s sleepy crew are awake, her cargo has been transferred to the pirate, which disappears in the darkness.

The Gray Ghost’s home port is Boston, where it is alleged she is owned by three men ostensibly insurance brokers, with offices on a prominent business street. She seems reasonably safe so long as she confines her depredations to liquor-bearing ships, for these vessels dare not appeal to the United States Government nor to the British authorities whose flag they fly.

But the residents of Newport and the vicinity are looking forward to a naval battle off the coast and are hoping it may not take place until the summer people have arrived. For the bootleggers, who are not the men to take losses calmly, are now planning to arm their vessels with one-pounders and machine guns and to augment the crews with experts in the handling of these arms.

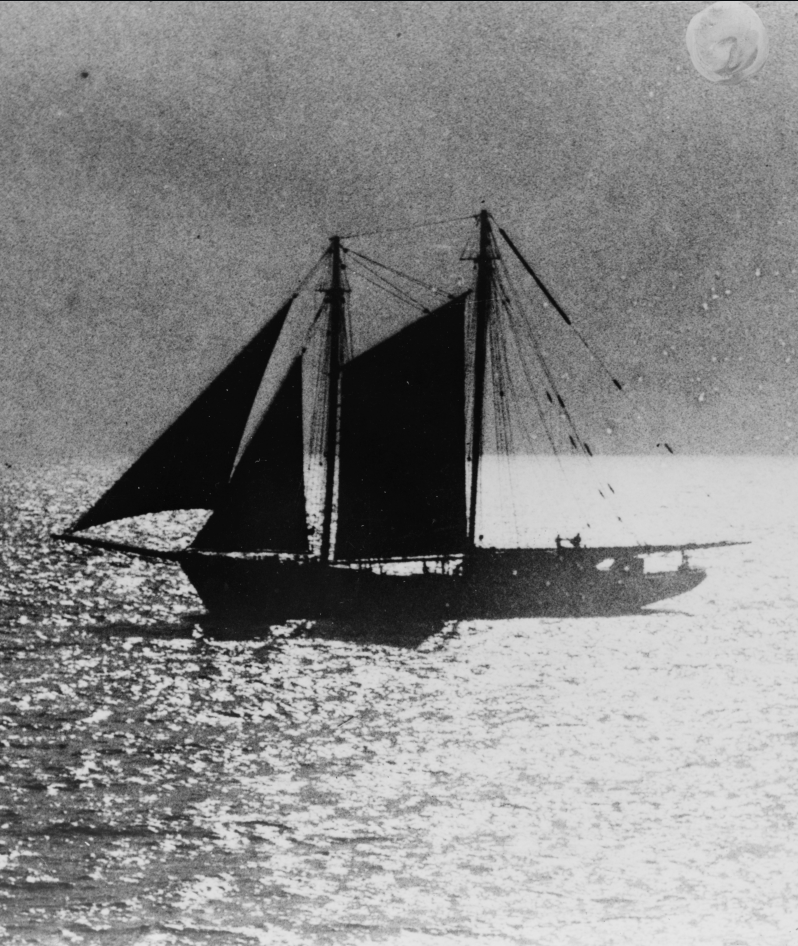

An “outside” supply ship carrying illegal liquor under sail. Many of the early outside vessels were sailing ships (Library of Congress)

Until this takes place the armada is basing its protection on a system of signals and general alertness. Thus it was that yesterday when a reporter and a photographer for The World sought to visit the fleet, they found the vessels with sails up and tacking and veering like a flock of frightened gulls instead of tugging at fathoms of anchor chain.

The Gray Ghost had visited the fleet as it lay at anchor two nights before, and had boarded a vessel and looted it of 1,700 cases of liquor, all it had on board. The pirate evidently had made a haul elsewhere, for it departed after this, but its morale effect was effective and enduring.

The signals are arranged between the captain of the vessel and its agent on shore. These financial men, as they are called, make their headquarters in one of the newest and largest hotels of Providence, R. I. Here the purchaser makes his payment and receives a note calling for so much liquor and also gets the station of the vessel and its code.

The purchase is not quite as simple a matter as this, of course. Even if you know that Mr. Smith stopping at the hotel is an agent for one of these vessels you can’t call him on the telephone and make a deal. Mr. Smith will instruct the prospective buyer to come to a certain room, and to come alone except for his bank roll.

When you arrive you will find that Mr. Smith is not alone, but has his gunman with him, and seeing this, you will not, if you are wise, argue with him or attempt to carry on the interview after the agent has announced it is closed. That is, not unless you happen to be a gunman yourself.

Not but what the prices will make you feel like arguing. The vessels are mostly laden with Lewis Hunter rye at $54 a case; Peter Dawson Scotch whiskey at $45 a case, and White Horse Scotch at $45 a case. They occasionally have some wines and champagnes, and the Transatlantic always will bring these on order.

The boat in which The World men made their trip is a nameless forty-foot craft which makes a steady ten knots an hour and is skippered by one of the men with a power boat on the surrounding shores who is not a rum-runner. This skipper specializes in carrying agents to and from the fleet, and reports it as more profitable and less dangerous.

A twenty-five mile run from Newport, R. I., brought us to Block Island, a noted summer resort which this winter has been turned into a bootleggers’ paradise. The four or five hundred fishermen who with their families comprise the island’s population are all members of either one or both of two great fraternal organizations, whose emblems may be seen painted on their boats.

Not only is Block Island a storehouse for much of the liquor from the fleet but virtually all of its men residents are engaged in running the whiskey, either to Rhode Island ports or to points on the Connecticut and Long Island shores of the Sound. Their clannishness long has been proverbial, but now it is doubtful if a stranger who did not promptly state his business and prove said business to be connected with this liquor trade, would be permitted to land.

The skipper did the talking and represented The World men as buyers seeking only 100 cases. This order could have been promptly filled there, but the guide said his passengers had a price of $45 a case out of Newport, which, as it would leave no profit for carrying the booze, was rejected with sneers.

A friend did volunteer the location and signal of one of a few general sellers of the fleet and the power boat departed. The only thing The World men received was an invitation to lose some money in one of the big crap games with which the captains and crews of the fleet entertain themselves on their infrequent visits ashore.

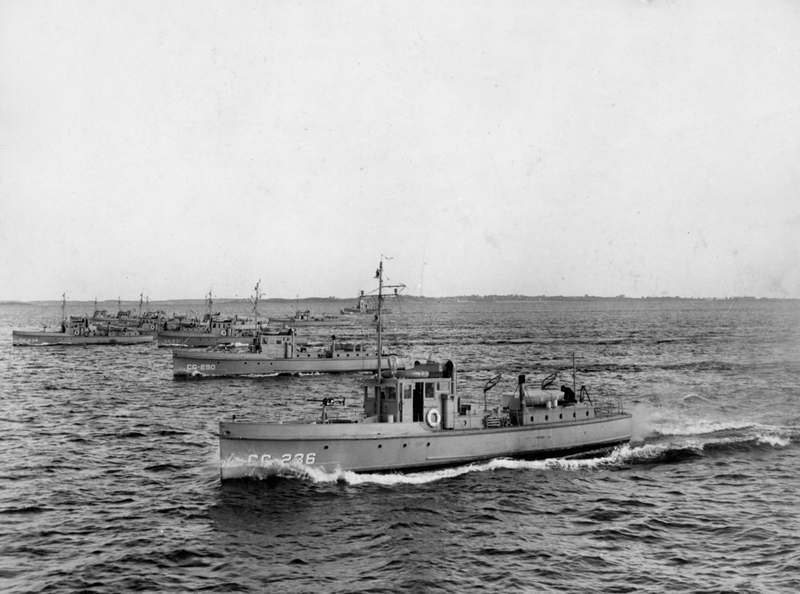

Coast Guard patrol boats, known at 75s, were the backbone of the Coast Guard’s effort against rumrunners (National Archives)

Now the signal might have been two white flags, one white flag or a black one, or even a red one or any combination of these, which are all in use, but it cannot be revealed. But whatever it was, it was not what the large converted yacht which was first picked up, ten miles beyond Block Island, itself the inner edge of the three-mile limit, was expecting.

The former yacht promptly displayed a pretty pair of heels as the reporters’ boat picked it up and the lookout picked up the news boat simultaneously through field glasses. None of the three schooners which soon were sighted responded to the signal, but tacked out to sea to avoid an approach and judging from their speed used their auxiliary engines along with their sails.

The skipper spat disgustedly and cursed the Gray Ghost as he swung about. There was no better luck with the three remaining members of the fleet sighted before the increasing roughness of the ocean and approaching darkness forced a return homeward. The general seller evidently had sold out his cargo or else he was the one the Gray Ghost looted. The others simply weren’t taking chances.

But from a man in a Connecticut city alleged to handle the rum traffic through that locality, The World reporter had learned the procedure of those who did the buying from the general selling ships. This will be told tomorrow.

Bargain day on Rum Row off New Jersey’s three-mile limit, carne to a sharp halt at dusk last evening when customs men and Coast Guards swooped down on returning rum buyers trying to make the home coast through the gathering murk.

The morning had been a pleasant one, and a comparatively calm sea lured a dozen buyers in power boats and tugs past Sandy Hook, according to the Associated Press. The liquor-carrying fleet had been increased to sixteen vessels—a huge and rusty old tanker, two nondescript steamers, twelve two-masted schooners and a battered three-masted bark.

It was just at dusk when the government men got into action. The old Army tug, Lexington, now used by the customs guards, saw a large auxiliary sloop making for the Long Island coast after visiting Rum Row. The Lexington intercepted the sloop off Rockaway Point. A government man was placed aboard and then the Lexington went after other prey. The Porpoise, a high-powered boat also used by the customs men, drove several vessels back to sea.

Coast Guard men commandeered a powerful rum runner in the Shrewsbury River and started toward the row. One vessel was stopped by the guards and others made for the open sea again.

When night came the liquor armada blazed with light. Huge anchor lights, of the type used in lighthouses, were hanging from each vessel. This action was believed to be in reply to reports of incoming steamship commanders that the armada is a menace to navigation.

Three small rum-runners were stopped by customs guards, but were found to have no liquor aboard.

The Boston Globe, in its March 16, 1923 edition, reprinted the above article under the heading, “Boston Pirate Craft Terror of Rum Fleet, Sea Battle Impends, as Block Island Smugglers Arm Against Dreaded Grey Ghost.” Chamberlin’s description of the Block Islanders seems spot on.

Wooden cases and barrels of illegal liquor on board an outside vessel, circa 1923. In later years rumrunners would use burlap sacks, which were easier to handle (Library of Congress)

I suspect Gray Ghost never existed. There is no indication of it I have found in official records. The New York World never followed up on its story. The vessel popped up in a story of a Scottish rumrunner who travelled to the Bahamas to supply rum ships with whiskey. The Scottish rumrunner heard stories about Gray Ghost appearing off Nassau and the response of rumrunners there sending out heavily armed ships to deal with the pirate ship.[2] But there is no indication they located the vessel. It may be that Gray Ghost was a composite of different pirate ships whose crew specialized in hijacking rum ships. Or it may be that Prohibition supporters concocted the story in order to scare off rum ships. In any case, there is no doubt that the rum ships on Rum Row, and the rumrunners they supplied, faced the risk of the loss of cargoes valued in the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars by pirate ships—as well as confiscation by the Coast Guard.

Notes

[1] Joseph Anthony, ed., The Best News Stories of 1923 (Boston, MA: Small, Maynard & Company, 1924), 38-42. [2] Netley Lucas, “Scotchman Relates Thrilling Tales of his Adventurous Trip to Rum Row,” Chattanooga Daily Times (Chattanooga, Tennessee), June 29, 1925.