At the outbreak of the Civil War, thousands of men flocked to enlist in newly established companies and regiments in the Union Army then organizing in small towns throughout the North. This raised a serious question: who would lead these men in battle? America had not fought a war in decades and had a tiny standing army. Only a relatively few officers from West Point graduated each year, and the veterans of the Mexican War were getting older. In any case, roughly half of them now served with the Confederacy.

The answer was that thousands of officers would have to learn through hard-fought experience, which raised another question: would appointments and promotions be made on merit or political connections—or both?

Isaac Peace Rodman of Rocky Brook, once a mill village located just north of Peace Dale, is a prime example of a home-grown officer who had little military training but stepped forward to organize a company of soldiers and, through both merit and political connections, earned promotions up the ranks. Remarkably, within one year, Rodman jumped from captain of a company to a brigadier general. The promotions, it turned out, were warranted. Before he was tragically struck down by enemy fire at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Rodman commanded a full division.

With the failure of the North and South to resolve the issue of slavery, the threat of Civil War loomed during the presidential election of 1860. War fears were heightened when, after the election of Abraham Lincoln, southern states seceded from the Union. They believed that the institution of slavery that they so ardently sought to preserve would be eventually destroyed with Lincoln’s election. (Even though Lincoln vowed only to stop the expansion of slavery, he did not believe he had the constitutional power to end slavery in the southern states where it existed).

In response, military preparations began in various northern towns, including in Rhode Island. Remarkably, many men in northern towns were willing to fight the South in order to preserve the Union and its new democracy. Later in the war, the fight would also morph into a war to free millions of enslaved people of the South.

In South Kingstown, some men acted quickly to muster future soldiers. The chartered company that had been organized in 1842 in response to the Dorr Rebellion, first called the Washington Cadets, then the Wakefield Cadets, and finally the Narragansett Guards, was revived. On April 19, 1861, a meeting of the outfit was held at the Court House in Kingston at 10 a.m. Men from Peace Dale, Wakefield, and Rocky Brook dominated the event. Prior to the meeting, 94 men assembled in Peace Dale and marched through Rocky Brook to Kingston. A total of 130 men enlisted in the company.

Isaac Peace Rodman of Rocky Brook was chosen as the revived company’s captain. Many of the men who had enlisted worked for his firm’s mills and admired him. Rodman then led the company for an hour of drilling with arms. Then the men were dismissed, with the request that they meet for drill every evening at one of three locations closest to their homes in Peace Dale, Wakefield and Rocky Brook.

Isaac and Mary Rodman built this still-standing stone house on Kingstown Road in Peace Dale in 1855 (Sharon Henderson)

The son of Samuel and Mary Rodman, Isaac Peace Rodman was born on August 18, 1822, at Rocky Brook. Some have speculated whether the use of the name Peace as his middle name meant that he was a Quaker. Indeed, the Antietam National Battlefield run by the National Park Service has a website article about Rodman stating that he was a Quaker and pacifist. That was not the case; the family had joined the Baptist Church in Wakefield. Isaac’s mother, Mary, joined the Baptist Church in Wakefield in 1829, and his father, Samuel, followed her shortly afterward. A short 1889 biography of Samuel Rodman states that he had been a member of the Baptist Church for over forty years and that in 1852 he was the primary donor of funds used to build the still-standing Wakefield Baptist meeting house. Records further indicate that Isaac joined the same Baptist Church in 1850. A short biography of Isaac’s life provides that, “He was for many years an honored member of the Baptist church,” and that he engaged in two activities not done by Quakers—at one time leading a men’s Bible class and another time serving as superintendent of its Sunday School.

The Peace name went back at least as far as his maternal grandfather, Isaac Peace, whose daughter, Mary Peace, was how Peace Dale got its name. Many of Isaac Peace Rodman’s ancestors from the eighteenth century were Quakers, not uncommon for long-established South Kingstown families.

Isaac’s father built a thriving mill business at Rocky Brook starting in 1838. The primary product of the mills was kersey cloth used as clothing for enslaved people in the South. Thus, the family profited from slavery in the South. The firm became one of the state’s most successful mill operators. (Two intersecting roads in Peace Dale still serve as a reminder of the mill business—Kersey Road and Paddy Hill Road. The latter inappropriate name was for the Irish mill workers who resided on the hill the road served and worked at the nearby textile mills operated by the Hazard family).

Young Isaac did not receive much formal education or military training. He attended public schools in South Kingstown, but as a young adult, Isaac joined his father’s firm. Those who knew Isaac were impressed by his natural intelligence and his extensive reading, including the classics. A biographical sketch of Rhode Island Civil War officers described Isaac as “extremely modest and retiring in nature.”

In 1847, Isaac married Sarah Lyman Arnold, daughter of a former governor of Rhode Island and member of the U.S. Congress. In 1855 the couple purchased a lot of land at the corner of Saugatucket and Kingstown roads. They built an attractive and spacious stone mansion that still stands today. The granite for the home was quarried locally. Well preserved and viewable from Kingstown Road (across from the police station), the home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Rodmans had seven children together, two of whom died early in life.

Isaac also served as president of the Wakefield Bank, and he had served for several years as president of the Town Council and a representative in the General Assembly. Rodman had participated in a small part of military life, serving as colonel of the Narragansett Guards in 1846. At the time of the muster in Kingston, he was serving his second term in the Rhode Island senate.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as president in the November 1860 election started a path of events that changed life for the Rodmans dramatically.

Father and son supported Republican Party moderates, including Abraham Lincoln. As Republicans, they likely opposed slavery. Meanwhile, orders from the South for kersey cloth dwindled. Once southern states seceded, they renounced most of their debts to northern creditors. The war crushed the Rodman firm’s mill business. The Rocky Brook Mill shut down in late May and a Wakefield mill after that. The family firm tried to hold on to their mills in order to secure military clothing contracts that were assumed would eventually be put out for bid. But father Samuel would manage the business.

Isaac was a friend of Governor William Sprague. The two had much in common. Both were sons of successful mill owners (although Sprague’s wealth was considerably greater), and both were strong supporters of the Union cause. Sprague, the “boy governor,” was elected as a Democrat in 1860, with the assistance of moderate Republicans. Sprague supported Rodman as the driving force behind the revival of the Narragansett Guards on April 7, 1861.

Five days later, the Confederates from South Carolina opened the war by bombarding and seizing the federal Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charlestown. Even though the Civil War ended his family’s business of making “slave cloth” to clothe enslaved people in the South, Rodman (as well as many of his mill workers whose jobs would be lost) eagerly supported the Union cause.

On May 4, 1861, meeting at the Court House in Kingston, the South Kingstown town meeting passed resolutions supporting President Lincoln in the full conduct of the war. The town meeting pledged that the town would assist the families of the men who enlisted and would pay enlistees $1 for every six hours of drilling. That same day, Captain Rodman received word that the Narragansett Guards would become Company E of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, then organizing in Providence.

On June 2, 1861, orders arrived requiring Company E to depart the Kingston railroad station in West Kingston for Providence on the afternoon of June 4th. Hearing that the troops would march through Kingston, Thomas P. Wells and his wife Mary offered to host a farewell party for them on the spacious lawn between their home and the Kingston Congregational Church. The officers of Company E accepted the offer. After marching to Kingston, the men of Company E relaxed on the lawns of Kingston’s houses on main street, drinking punch and eating food brought to them by villagers. Music filled the air, and women and girls had one last dance with their beaus. The minister of the Kingston Congregational Church, as well as Thomas P. Wells, gave reassuring speeches. Captain Rodman then announced that it was time for the soldiers to depart for the train. Wakefield’s new newspaper, the Narragansett Times, reported:

About 3 o’clock the volunteers formed in front of the Court House, and escorted by the Home Guards marched to the depot. A long train of vehicles proceeded and followed the companies, and the roads were thronged with people on foot. The procession occupied the whole slope of Kingston Hill extending nearly half a mile. Good judges estimated two thousand persons were at the station. There were many women and children who had come to say farewell to husbands, fathers and brothers. There were many parents, past the prime of life, who had come to bid their sons Godspeed. There were many moist eyes and quivering lips, but the moist eyes and quivering lips bespoke an emotion which did honor to the heartbeating beneath.

The 2nd Rhode Island Regiment was commanded by Colonel John S. Slocum, a solid officer with experience in the Mexican War. On June 7, the regiment paraded through Providence, ending at Exchange Place, where they heard a speech from Stephen A. Douglas, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate whom Lincoln had defeated.

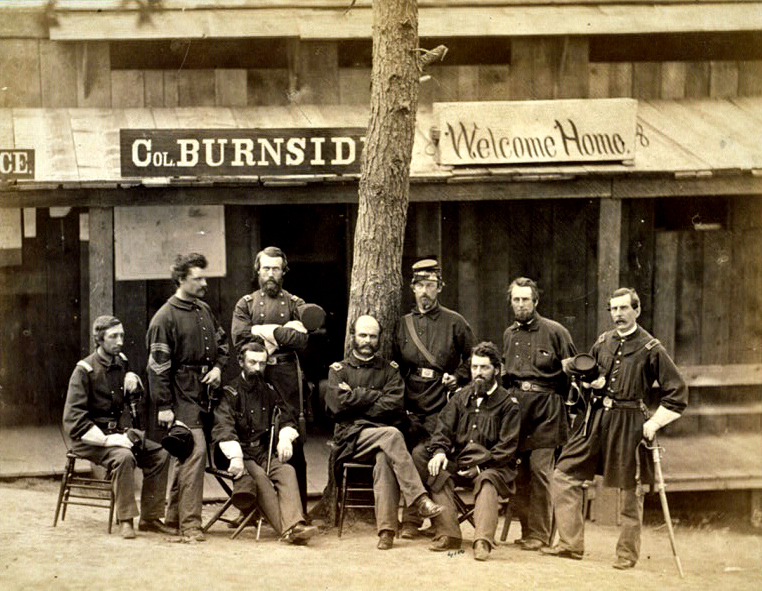

Colonel Ambrose Burnside and his officers pose for a photograph in Rhode Island in 1861. The officers are probably from both the 1st Rhode Island Regiment and 2nd Rhode Island Regiment. Captain Rodman of the 2nd Rhode Island leans against the tree (Library of Congress)

Early in the Civil War, Captain Isaac Peace Rodman quickly became a favorite of the highest-ranking Rhode Islander in the Civil War, General Ambrose Burnside of Cranston. Burnside was impressed with the conduct of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers in the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. Company E and the rest of the regiment fought like veterans for much of the day, including against the famed “Louisiana Tigers” from New Orleans. But Colonel Slocum was wounded in the action and later died. Major Sullivan Ballou of Providence also was killed in the battle—he is best known for penning a remarkable love letter to his wife before the battle.

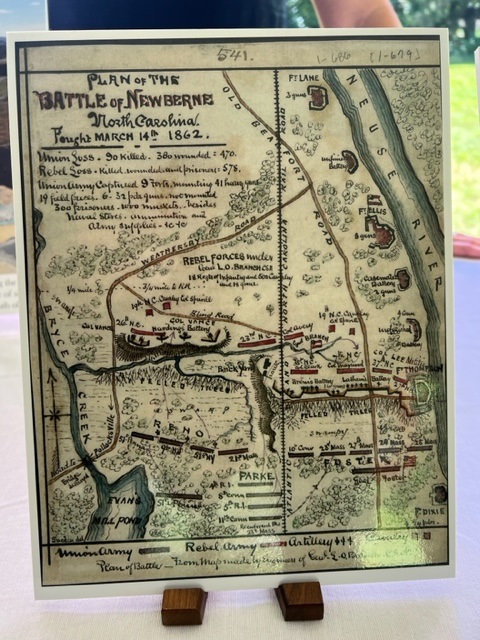

Burnside detached Rodman from Company E, and Governor Sprague appointed his friend as colonel of the 4th Rhode Island Regiment. Rodman distinguished himself at the Battle of Roanoke Island on February 8, 1862. On March 14, 1862, at the battle of New Bern, in North Carolina, at the crucial moment, Colonel Rodman on his own initiative ordered his troops to make a bayonet charge, routing the surprised Confederates and capturing a key battery. General Burnside thought Rodman’s action the highlight of the Union’s effort. Governor Sprague in a private letter described Rodman as the bravest man he ever knew. Rodman was promoted to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers, effective April 28.

Map of the Battle of New Bern in North Carolina, March 14, 1862. Colonel Rodman’s 4th Rhode Island can be seen at the bottom center of the map under General Parke’s name. A summary of the battle from the Varnum Armory Museum states in part: “Col. Rodman decided without orders to make the charge. The 4th Rhode Island men charged headlong into the fray yelling and cheering with fixed bayonets. Despite “murderous fire” from the enemy, the Rhode Islanders reached and burst through the lines getting in their rear fighting desperately hand-to-hand. This began a general breakdown in the Confederate forces. After capturing many men, weapons and equipment, and nine brass field guns, the 4th Rhode Island made a second successful charge in a different direction in support of Union forces on the left. The beaten Confederates retreated in haste back to New Bern.” The map is in the possession of The Varnum Memorial Armory Museum in East Greenwich and was being displayed at the Isaac Peace Rodman Stone House by Erica Luke and Caleb Goodhouse of the South County History Center on August 19, 2023, after a celebration honoring Colonel Rodman at Riverside Cemetery in Wakefield (Photo by Christian McBurney)

Confederate Artillery Guidon captured by the 4th Rhode Island Volunteers during its hectic charge at the Battle of New Bern, March 14 ,1862. The caption provides that it is on loan from Providence Marine Corps of Artillery Museum of Rhode Island Military History. The flag is in the possession of The Varnum Memorial Armory Museum in East Greenwich and was being displayed at the Isaac Peace Rodman Stone House by Erica Luke and Caleb Goodhouse of the South County History Center on August 19, 2023, after a celebration honoring Colonel Rodman at Riverside Cemetery in Wakefield (Photo by Christian McBurney)

Rodman was struck down with a recurrence of typhoid fever. His doctor and General Burnside insisted that he return home to recuperate. On his arrival at Kingston Station, he was met by a large delegation of local citizens, militia companies and a music band. But he was too weak to say but a few words to the welcoming crowd.

Elizabeth Hagadorn, daughter of Kingston’s Thomas R. Wells, wrote in a letter dated July 9, 1862, that when Rodman visited Kingston, he informed her that he “feels as well as ever save his strength” and that he was “anxious to be at his post.” But she noted that Rodman was “still very thin and his limbs tremble very much when he walks.”

When Rodman’s health was only partially restored, General Burnside wrote to him, asking that he return to the field in anticipation of a great battle. The Confederate Army was readying to cross the Potomac River and invade Maryland. Against his physician’s advice and with his furlough not yet concluded, Rodman obeyed and departed Peace Dale at once. The Narragansett Times reported that General Rodman considered himself in “good fighting condition” before his departure.

On his way, Rodman attended a large rally in Providence on August 4, appealing to the large crowd to speed up recruiting efforts. Four days later the South Kingstown Town Council voted to pay a bounty of $500 to each of 97 men, part of 300,000 recruits sought by President Lincoln. The large bounty indicated that enthusiasm for the war had waned from its opening days.

General Burnside placed Rodman in command of the 3rd Division in the Ninth Corps of the Army of the Potomac as it marched to catch up to Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The division consisted of an artillery unit, three New York regiments, three Connecticut regiments, and the 4th Rhode Island Regiment—in total 3,200 soldiers. On September 14, 1862, Rodman ably led his division in the Battle of South Mountain. General Burnside again singled out General Rodman for praise, stating the Rodman had demonstrated a “military genius of high order.”

Brigadier General Isaac Peace Rodman by James Sullivan, circa 1863. Sullivan painted the portrait from an 1862 photograph of Rodman in a similar pose. The painting hung in Brown University’s Memorial Hall (Brown University Portrait Gallery)

On September 17, Rodman and his 3rd Division, along with the rest of the Union Army under General George McClellan, fought on the bloodiest single day of the war in the Battle of Antietam. During the battle, the 3rd Division was stationed close to what is now known as Burnside Bridge along Antietam Creek. One of Rodman’s regiments, from Connecticut, made a charge across the bridge but had to withdraw after suffering heavy casualties.

During the assault, at 9:00 a.m., Rodman led the rest of his 3rd Division south, farther downstream, to find a place where his troops could ford and flank the enemy defending the bridge. It was not until around noon that Rodman’s men successfully located and secured the waist-deep crossing at Snavely’s Ford, about a mile from the bridge. By 1:00 p.m., the soldiers had crossed the creek and established a position.

Rodman waited to receive orders to attack, but they were delayed. Meanwhile, his men hunkered down from fire by enemy sharpshooters and artillery. Then one of his regiments, the 16th Connecticut, got lost in the thick underbrush. The element of surprise against the Confederate defenders at Burnside Bridge had been lost by the delays. But other divisions of the army had subsequently also crossed the creek. The Confederate defenders fell back. General McClellan, unhappy with the delay, ordered Burnside’s IX Corps to attack towards the nearby village of Sharpsburg.

A photograph of what is now called Burnside Bridge, taken within days of the Battle of Antietam (Library of Congress)

Finally, at about 3:00 p.m., the IX Corp’s attack began. The men of the 3rd Division climbed up the slopes and charged ahead. At first, they pushed back the enemy toward Sharpsburg. At the far left of the Union line that stretched for some three miles was the 4th Rhode Island and the 16th Connecticut, a green regiment. The regiments were slowed by the rough terrain and fields of corn.

Unknown to either Burnside or Rodman, the Confederates had just received substantial reinforcements after a rapid march from Harpers Ferry. At about 4:00 p.m., these reinforcements, under General A. P. Hill, smashed into the left flank of Rodman’s division—the green Connecticut regiment and the 4th Rhode Island. The two regiments tried to hold on, but as one soldier described they “stood for a few minutes trying to rally, swept by a destructive cross fire . . . Men were falling on every hand.” The Connecticut troops were first routed and ran, and soon the Rhode Islanders did the same.

Rodman quickly recognized the stakes: he had to avoid his division—and even the entire IX Corps—from being overrun and rolled up. The general gave an order that had worked before: for his men to charge the enemy with bayonets secured to their muskets. Waving his saber high above his head while riding on horseback, Rodman led the charge—directly into devastating artillery fire from Confederate cannon. Suddenly, he felt a sharp pain in his chest, and he slumped in his saddle. A Minié ball from a South Carolina sharpshooter’s rifle had pierced his left lung and had passed through is body. Amid the clamor of battle, he fell off his horse and onto the ground. Meanwhile, the bayonet charge had petered out under heavy fire.

Hill’s flank attack succeeded. The entire IX Corps collapsed from left to right. The remnants of Rodman’s division, as well as other survivors of the IX Corps, retreated and fell back towards Antietam Creek. The firing slowed and battle ended at about 5:30 p.m. The 3rd Division’s casualties amounted to 1,255 killed, wounded or missing—an awful and astounding rate of 39%.

Recent photograph of Burnside Bridge spanning Antietam Creek. It is a beautiful spot for viewing and also for hiking to Snavely’s Ford and the location where Brigadier General Rodman was mortally wounded (National Park Service)

Rodman was taken to a nearby field hospital. Burnside later stopped by to see and comfort his friend. No doubt Burnside knew that Rodman was dying, as was the case with most soldiers with chest wounds. The efficient Union staff immediately notified Rodman’s family of Isaac’s having been wounded and family members rushed by train to be at Isaac’s side.

Rodman lingered for thirteen days until the evening of September 29 or early morning of September 30, when he expired. Among those at his side were his wife Sally and his father Samuel. Isaac was forty years old when he died.

Rodman’s body was brought to Providence where it lay in state in a metal casket in the Rhode Island House of Representatives with full honors. It was the first time the Rhode Island State House had been used for a public funeral.

He remains Rhode Island’s highest-ranking officer killed in combat. The Providence Journal reported, “Upon the casket were the cap, sword, and belt of the deceased, and wreaths of evergreens and flowers. The hall was open to the public from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. and during the time was viewed by several thousand people.” Soldiers from the Narragansett Guards and Pettaquamscutt Light Infantry functioned as the honor guard.

Henry B. Anthony, then serving as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, eulogized Rodman appropriately by emphasizing how he had succeeded in rising, mostly by merit, in a brief time from having virtually no military experience to command a division:

Here lies the true type of the patriot-soldier. Born and educated to peaceful pursuits, with no thirst for military distinction, with little taste or predilection for military life, he answered the earliest call of his country, and drew his sword in her defense. Entering the service in a subordinate capacity, he rose by merit alone to the high rank in which he fell; and when the fatal shot struck him, the captain of a year ago was in command of a division. His rapid promotion was influenced by no solicitations of his own. He never joined the crowds that throng the avenues of preferment. Patient, laborious, courageous, wholly devoted to his duties, he filled each place so well that his advancement to the next was a matter of course, and the promotion which he did not seek sought him.

After the funeral service, soldiers escorted Rodman’s casket to rail cars at Providence Station. Rodman’s body was brought by train to Kingston Station, and then by horse-drawn funeral coach to his home in Peace Dale. More than a thousand mourners came to pay their respects, based on the procession that passed through Kingston, which extended the full two miles from the railroad station. This occasion was in sad contrast to the high hopes that townsmen felt on June 4, 1861, when Company E stood in front of the Court House before departing for war.

The Soldiers and Sailors Monument honoring fallen military personnel from South Kingstown in Riverside Cemetery, Peace Dale. General Rodman is listed (Sharon Henderson)

On Sunday, October 5, the final funeral service for Rodman was conducted before of an immense crowd—estimated at almost 1,500 by the Narragansett Times. The body was interred in the small family cemetery within a farm, located off Emmet Lane in Peace Dale. The cemetery lay atop a sandy hill enclosed by a low stonewall. Three volleys of musketry were fired over the grave, ending the ceremonies.

At Antietam National Battlefield, a sign along Antietam Creek at Snavely’s Ford marks the spot near where Rodman made his charge and fell mortally wounded. Antietam Battlefield is the best-preserved battlefield in the East, and it is a marvelous walk from Burnside’s Bridge, south along the creek, and then to the sign.

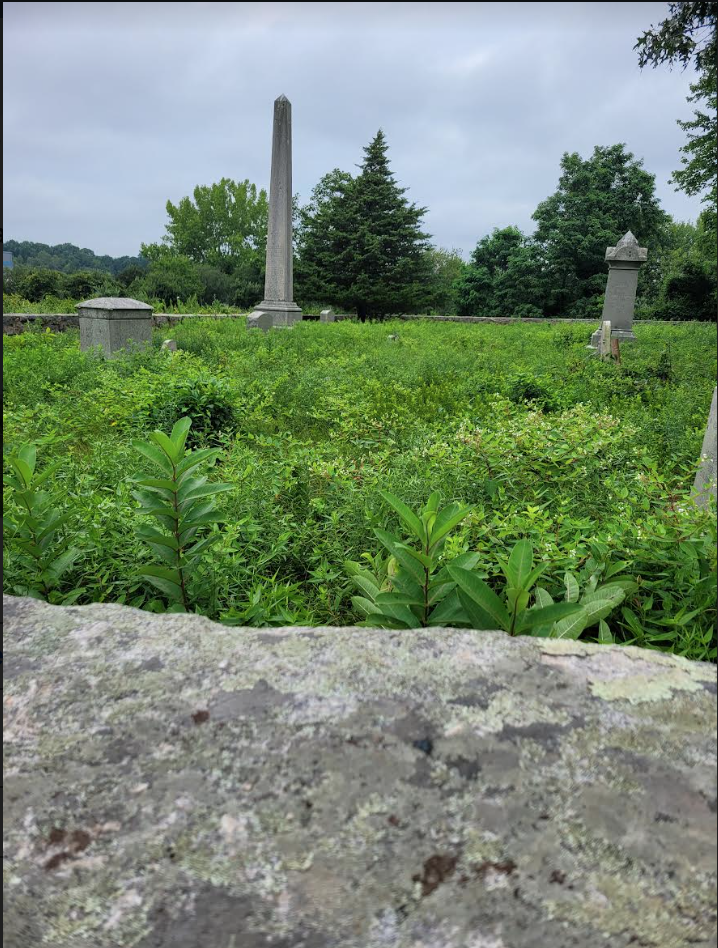

Today, an impressive obelisk marks Rodman’s gravesite in Peace Dale. Unfortunately, the Rodman family cemetery is overgrown with vegetation and the gravesite is in poor condition. The location is an eyesore and covered in ticks and poison ivy. I personally saw this ten years ago and it appears the situation has worsened since then. The cemetery is surrounded by a sand and gravel business, so access is permitted only with permission of the business owner. It is not the job of the business to care for the cemetery. On occasion, about once a year, local Boy Scout troops and Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (Rhode Island Department) spend a day or so trying their best to restore and maintain the cemetery and the general’s gravesite. But perpetual maintenance is needed. It is my belief that Isaac Peace Rodman should be properly honored by moving his grave and marker to a location accessible to the public in Peace Dale or Wakefield.

View from outside the Rodman Family Cemetery towards General Rodman’s obelisk July 23, 2023, before the overgrown vegetation was cut back. It was difficult for the photographer to work her way to reach the stonewall to the cemetary due to similar overgrowth outside the cemetery (Sharon Henderson).

View of the Rodman Family Cemetery from a side of the stonewall towards General Rodman’s obelisk. This was taken August 10, 2023, much but not all the overgrown vegetation was cut back. Ticks and poison ivy remain (Sharon Henderson)

Sources

Main Sources:

Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900 (Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 253-55, with footnotes including citations to original authorities at 358.

Robert E. Gough, “South Kingstown’s Own: A Biographical Sketch of Isaac Peace Rodman Brigadier General” (2011), Special Collections (Miscellaneous), Paper 20, University of Rhode Island Library. Also at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/sc_pubs/20.

Patrick J. Conley, The Leaders of Rhode Island’s Golden Age (History Press, 2019), 21-23.

“Isaac Peace Rodman.” Antietam National Battlefield, National Park Service, posted 2018. Online article at https://www.nps.gov/people/Isaac-peace-rodman.htm.

Narragansett Times, Oct. 3 and 10, 1862. Accessed at the South Kingstown Public Library’s website, at https://www.southkingstownri.com/993/SKPL-Digital-Collections.

Ted Ballard, Battle of Antietam (Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2008), 38-42.

“The Final Attack Trail.” National Park Service brochure, 8. Accessed at http://npshistory.com/brochures/anti/final-attack-trail.pdf. (This is the clearest explanation of the action involving Rodman’s division late in the day at Antietam that I have located.)

- R. Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island (W. W. Preston & Co., 1889), 524-27 (short biography of Samuel Rodman) and 528-530 (short biography of Isaac Peace Rodman).