I have lived with the ghosts of the past for over twenty years. Since early in 2000 when I discovered that I had a great-great-great uncle, Alfred Sheldon Knight, who served in the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War and died in Federal service, as well as two other triple great uncles who were in the First Rhode Island Light Artillery, Moses O. Knight and Almond L. Field, the Civil War has defined my life.

In nearly a quarter of a century of non-stop work, I have produced fifteen books; written so many articles I cannot count; lived and reenacted the war as a Union soldier; worked as a National Park Ranger at two Civil War parks; earned an advanced degree in the field of history with a focus on nineteenth century American history; walked many of the battlefields that Rhode Islanders fought on; visited every library, museum, town hall, archive, and other repository in Rhode Island searching for information on Rhode Island’s Civil War volunteers; and perhaps for me most importantly, visited the final resting place of nearly every man buried in Rhode Island and elsewhere around the United States who served in Rhode Island units during the Civil War. Even from my current home in northern Vermont, I continue to find and visit Rhode Islanders buried in the Green Mountain State. Furthermore, I have collected and continue to collect the physical remnants left behind by those who served, including their letters, photographs, and relics. My wife frequently states our house resembles an antique store rather than a home. It is rather odd that I have become known as the “go to guy” for Rhode Island military history, with my phone constantly blowing up about the Civil War.

Second Lieutenant Charles E. Douglas of Providence was a jeweler who first served three months as a member of the First Rhode Island Detached Militia. As an officer he served three years in North Carolina with the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

I wrote, what I said would be my last article for Rhode Island Roots in 2018, when I became a father for the first time. The temptation of writing in the free time that I had, however, in the intervening five years was too great and I decided to pen the occasional article which has graced these pages in that time. In that time as well, I have added another daughter and a son to my brood, and the little free time that I now possess is filled with feeding mush to my son, coloring with my daughters, and reading the same books over and over to an enthralled audience. They are moments that I truly cherish and ones that make my life truly worth living, rather than spending countless hours sitting in a library or pursuing some long-lost memoir. I enjoy now living in the moment, rather than living in the past. Although when I do have a spare moment, which is rare, the reading of an old letter or staring at the face of a literal kid, a teenager, who died to preserve the institution of American democracy brings the past back to life.

As I approach forty and enter retirement from writing history, I want to leave readers with what I consider to be two of the most important writings about Rhode Island’s participation in the Civil War. Both answer important questions. The first question is why. What led Rhode Islanders to volunteer en masse to go and fight their fellow Americans? The second is remembrance: how was this bloody mess of a war remembered by those who took part in it?

Both of these pieces were written by Frederic Denison. A Brown educated Baptist minister from Westerly, he was an extraordinary individual. A self-declared member of the “church militant” and a fervent abolitionist, Denison went to war armed with sabre and revolver and took part as a participant in several battles. A gifted writer as well, his field diaries and other papers at the Westerly Public Library are a remarkable source about the war and his participation as the regimental chaplain of the First Rhode Island Cavalry and Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. Fortunately, though, for posterity, Denison published two books in the 1870s about the two regiments he served in. In 1876, he wrote, Sabres and Spurs: The First Regiment Rhode Island Cavalry in the Civil War, 1861-1865. Its Origin, Marches, Scouts, Skirmishes, Raids, Battles, Sufferings, Victories, and Appropriate Official Papers; with The Roll of Honor and Roll of the Regiment. In 1879, he returned with Shot and Shell: The Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiment in the Rebellion, 1861-1865. Camps, Forts, Garrisons, Marches, Skirmishes, Sieges, Battles, and Victories; Also, The Roll of Honor and Roll of the Regiment. Both titles are quite the mouthful, but together they rank as perhaps the finest written record by a Rhode Island participant in the Civil War.

I have often wondered what led nearly 24,000 men from my native state to go to war from 1861-1865. I have found several different answers in the writings left behind by these men. For Captain Peleg E. Peckham of the Seventh Rhode Island, it was an economic opportunity. A barely getting by carpenter from Charlestown, Peckham turned his military service into a financial opportunity for his family. Tragically, however, he would be killed in one of the last battles of the war.

For Elisha Hunt Rhodes of Cranston, it was the opportunity to leave a boring clerk job in Providence, see the world, and serve his country. The war did two things. It reinforced the idea that the United States was an indissoluble nation where republicanism would triumph and where a free-market economy would triumph over the institution of slavery. Many Rhode Islanders rarely or never encountered Black people in their native state. They may have known that in colonial Rhode Island, Black people had once been enslaved, but were now free. Whey stationed in the South during the war, Rhode Island soldiers saw Blacks everywhere—and in a state of enslavement. Many Rhode Island veterans would not publicly state that emancipation was a reason why they volunteered, but the sacrifice of the 2,217 known Rhode Islanders who died in the Civil War paved the way for the freedom of four million Americans held in bondage.

Private John Rice Arnold of Providence died of typhoid at his family home on July 30, 1861, shortly after returning from the front. He had served in Company D, First Rhode Island Detached Militia (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

It is said that while the Union won the war in the field, while the South won the war in the history books. For nearly 150 years Americans were force-fed the idea that the war had nothing to do with slavery, that it was really about “States Rights.” Only after the senseless extrajudicial, filmed killings of so many African Americans and the Blacks Lives Matters movement has this pointless narrative changed. The horrendous monuments to a rebellion against the government are finally coming down and the narrative is being corrected. The war was fought over the issue of slavery, period. Nothing else.

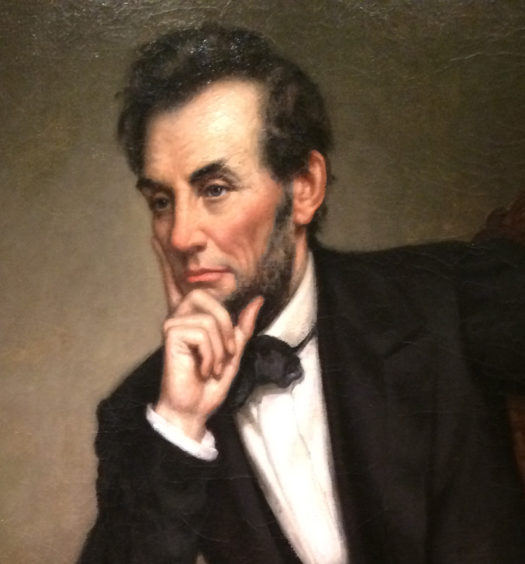

Frederic Denison was a man way ahead of his own time. In his 1879 book, Shot and Shell, the good chaplain stated plainly what the war was fought over:

However the fact may be disguised by special pleading, the signal gun of our Civil War was forged and fired by Slavery. In that hoary abuse was born and developed the giant Rebellion. The North had thrown off the ancient semi-barbaric system. The young and growing West had resolutely refused to adopt the depressing, thriftless wrong. In the South, however, the slaveholders educated and deeply involved in the peculiar institution, regarded it as justifiable and even Christian, and could not brook the opposition and reproofs brought against it by the majority of the nation. Adopting, therefore for a plea, and conscientiously on the part of many the theory of state rights as against the national sovereignty, the slave states finally planned and inaugurated the disastrous revolt.

It is hard to believe the above was written in 1879. Still, many white Americans living in the South continue to clench and resolutely hold on to the belief that the war had nothing to do with slavery. Fortunately, they are in the minority and hopefully will be the final generation to buy into this frivolous nonsense.

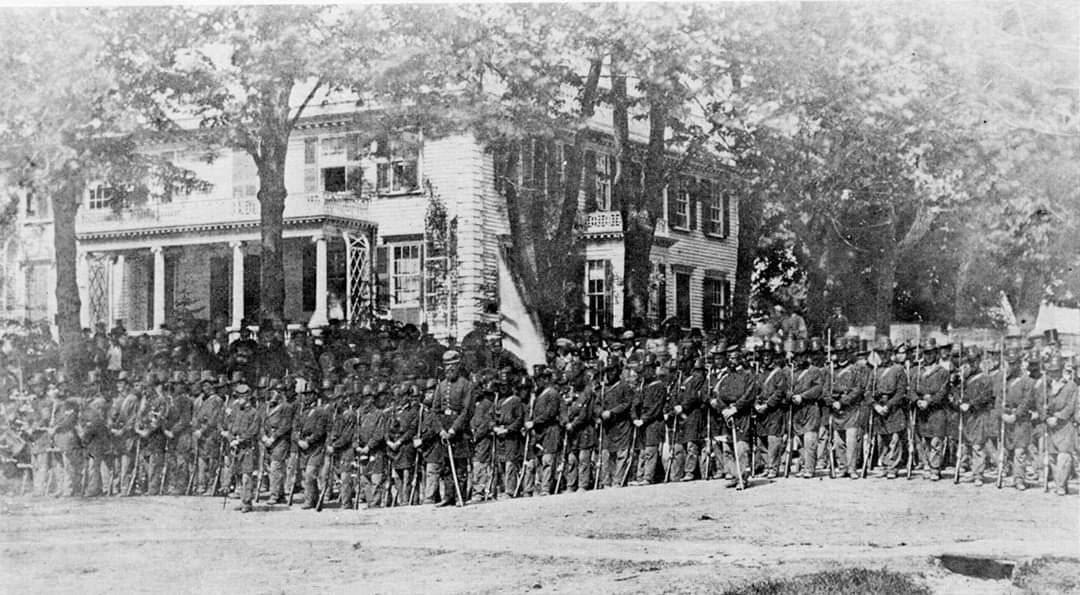

Company G, Second Rhode Island Volunteers, mustering into Federal service, June 1861 (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

After spending several pages discussing the events that led to the election of Abraham Lincoln firing on Fort Sumter, Denison concludes with the end result of the conflict that saw 750,000 Americans perish, the nation restored whole, and an entire people freed:

It may be said that our Revolutionary War with England was our nation’s natural birth. But in our Civil War our nation experienced its regeneration—a second and diviner life. The first war gave us personality and independence. The second war gave us freedom, manhood, brotherhood, and unconquerable principle. Moreover, it virtually decided the character and fate of North America, as well as of our country. In short, never was there a more important war on the face of the earth. Slavery battled with Freedom and fell. It dug its own grave and perished in endless disgrace.

Chaplain Denison could certainly write and fourteen years after the end of the war knew what had been purchased by the costly sacrifice of so many.

Secondly, I often wonder, how did Rhode Islanders remember the war? From the start, Rhode Islanders were front and center in remembering the conflict. In the summer of 1862, another chaplain, Augustus Woodbury, wrote A Narrative of the Campaign of the First Rhode Island Regiment, in the Spring and Summer of 1861. This was literally the very first published regimental history written about a Civil War unit and set the standard by which all others, including those I have written, have been published in the last 160 years. In 1868, the newly incorporated City of Woonsocket erected the first Civil War monument in Rhode Island; roughly a third of the cities and towns in Rhode Island would follow. In 1871, the State of Rhode Island dedicated the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Providence. This is remarkable, as it is the ONLY state memorial to list the names of everyone from a state to perish in the war. While an extraordinary triumph, unfortunately, the state missed the names of nearly 500 men who died as a direct result of their military service; I remedied this oversight in my 2018 book, Rhode Island’s Civil War Dead.

As a budding historian twenty-five years ago, I believed what I had been told that nearly every Civil War veteran returned back to their hometowns and instantly joined the Grand Army of the Republic (a national organization for veterans), spending the rest of their life in almost perpetual mourning, remembering the war, decorating comrades’ graves, and reliving the war as a daily experience. Central to this was attending Grand Army meetings and dedications, as well as meetings of their regimental veteran association. This description could not be further from the truth.

At its peak, in 1888, the Rhode Island Department of the Grand Army of the Republic had about 2,300 members in twenty-three posts around Rhode Island. A good many of these were men who had moved to Rhode Island after the war, seeking economic opportunity in the many mills in the state. Of the veterans who had served in Rhode Island Civil War units, the overwhelming majority were from veterans who served in the First Rhode Island Detached Militia, as well as the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, and the Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Rhode Island Volunteers. These units saw little or no combat. Surprisingly, the Grand Army was integrated in much of Rhode Island, with the occasional Black veteran as a member. In Providence, however, the association was segregated, with Black veterans in the city being forced to join the Ives Post. (I have been searching for the Ives Post records for ten years and have yet to get a major lead!)

The majority of the men who served in Rhode Island’s major combat units—the Second, Fourth, and Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, the First Rhode Island Cavalry, as well as seven of the eight batteries of the First Rhode Island Light Artillery—largely wanted to forget about the war. Writing about the Civil War veterans from western Rhode Island, Clarence M. Webster stated, “They had helped the town do a job and now they were free to live as they pleased. There wasn’t any sense making a to-do over them; they’d been good soldiers, none better, but the war was over. That was what my grandfather thought of the Civil War when he came home from it. It was over.” The men had done their duty, the Union was restored, the slaves were freed, and the veterans wanted to get on with life in the factory or back on the farm. Of roughly 950 men who survived their service in the Seventh Rhode Island, a unit that saw one in five of its members die in the service, only 150 ever joined the Seventh Rhode Island Veteran Association, and of these the best attended reunion only had about sixty veterans present.

First Sergeant Jeremiah P. Bezeley of Company B was shot in the head at Cold Harbor and lived (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

As I noted at the beginning, I have lived with the ghosts of the Civil War for a quarter of a century. Although I never had the privilege of serving in uniform, having selected to serve my country in the civil, rather than military service, I sometimes feel that the memories I have of the last two plus decades are the best of my life. Indeed, in some ways they are, but in others, watching my children grow are even better. Perhaps it was the same for the men who wore the blue from Rhode Island and were fortunate enough to return to Rhode Island to start new families or join their existing ones and live to be old men. The memories they made in their youth would never leave them, but it was because of those memories created in their youth that defined and shaped who they were in the ever-changing America they helped forge.

I leave you, as Frederic Denison did in his 1876 book, Sabres and Spurs, with the following:

Let your helm adorn your cottage;

Let your belt hang on the wall;

Keep your knapsack as a relic;

Guard your sabre in your hall;

Hold your spurs all marred by battle,

And your bullet-riven blouse,

With the bloody grime upon it,

As the jewels of your house.

Of these we will tell our children,

Proofs of valor and of scars,

And will bid them guard your memory

While they hold the Stripes and Stars.