There were five or six duels fought in General Rochambeau’s army, three of them in Newport, Rhode Island in 1780 and 1781. Frenchmen can be irascible and easily offended, so it should come as no surprise that French military officers who have been relatively idle for a long time turned to fighting each other when they had no enemy to engage. Morris Bishop comments, “All too many gentleman officers seemed bent on killing friend instead of foe.”[1]

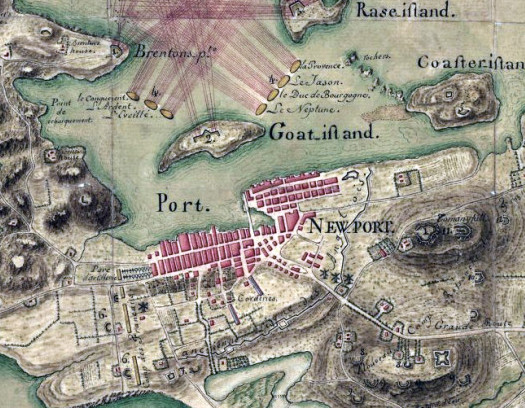

When his French army occupied Newport from 1780 to 1781, General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur Comte de Rochambeau had to deal with three duels among his aristocratic officers.

Fatal judicial duels became so frequent in France that attempts were made to reduce them since the 12th century. The last one to be authorized by a French king took place on July 10, 1547. Duels of honor became so prevalent in France that Charles IX issued an ordinance in 1566 ordering anyone taking part in a duel to be punished by death. However, the practice survived longer than did the French monarchy.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly fought with swords (the rapier, and later the small sword). Beginning in the late 18th century in England, duels were more commonly fought using pistols. Duels were occasionally fought between women. From the Revolutionary period onward, duels became the way to settle political disputes. Political duels were frequent in the 19th century. The last official duel in the history of France occurred on April 21 1967.[2]

One of the duels fought in Newport was between two of the most prominent French officers, Louis-Marie d’Ayen, viscount de Noailles (1756-1804) vs. Robert Guillaume Dillon (1756-1804). Another also had two high-ranking French aristocrats facing one another, Armand Charles Augustin de La Croix, Comte de Charlus, then duc de Castries (1756-1842), and Alexandre Theodore Victor chevalier de Lameth (1760-1829).

This article focuses on the Newport duel fought between Louis-François-Bertrand du Pont d’Aubevoye, Comte de Lauberdière (1759-1837) and Denis-Jean-Florimond Langlois de Montheville marquis du Bouchet (1752-1826). Lauberdière was General Rochambeau’s nephew and aide-de-camp. At 21-years old, he was the youngest member of Rochambeau’s staff.[3] Du Bouchet was seven years older and a brigade major of the army. He was also the brother-in-law of Irishman Thomas Conway (1733–1800), who served as a major general in the Continental Army.

A miniature of the comte de Lauberdière is on the cover of Norman Desmarais’s book, The Road to Yorktown: The French Campaigns in the American Revolution, 1780-1783, by Louis-François-Bertrand du Pont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdière.

Lauberdière’s journal[4] glosses over the duel with very little commentary other than for justifying his actions. Du Bouchet’s journal[5] gives us much more information. In early June 1781, as the army began preparing for its departure, du Bouchet was ordered to remain in Newport. He would be part of a detachment of 400 men (100 from each regiment) under the command of Claude Gabriel Marquis de Choisy (1723-1800)[6] to protect the city and the transport vessels and to guard the siege artillery still at Newport.

Du Bouchet, anxious to attain glory, was impatient to engage the enemy in combat and to make his reputation. He perceived his new orders as a humiliation. General Rochambeau tried to revive his spirits by telling him that the artillery would rejoin the army at a later time and that the main army could capture nothing without de Choisy’s detachment. Still, du Bouchet felt shame at the thought of the army marching to combat while he remained in the rear.

Believing himself bereft of honor, his dejection made him incapable of listening to reason. He admitted he was on the verge of insanity. Brigadier General de Choisy invited him and the Count de Lauberdière to dinner one evening in early June 1781. When Lauberdière learned that du Bouchet would not be accompanying the army on its march, he surmised du Bouchet would not need his horses, so, during the dinner, he asked to buy them.

Du Bouchet perceived the offer as irony and mockery and believed it was intended to humiliate him and to remind him of his disgrace. He became very angry and responded with bitterness and resentment. Feeling his honor had been attacked, Lauberdière could not ignore the response in silence. He returned an hour later with Mr. de Mauduit[7] to demand satisfaction and introduced Mr. de Mauduit as his witness.

Du Bouchet said he was extremely busy preparing orders for the army’s departure and asked Lauberdière and Mauduit to be seated for about half an hour or so, after which he would be free and entirely at their disposal. He told them that he knew that certain wrongs could not be repaired and agreed to a duel with Lauberdière, who was younger and “had to make his reputation even more than I did.”

While this was Lauberdière’s first duel, it was not so for du Bouchet. When he was fifteen and a student at a French military academy, one of his classmates challenged him to a duel to make a reputation for himself. The duel was fought at 10 o’clock at night in the moat around the town. Du Bouchet received five wounds before the duel was halted. His opponent was dishonorably discharged from the academy the next day.[8]

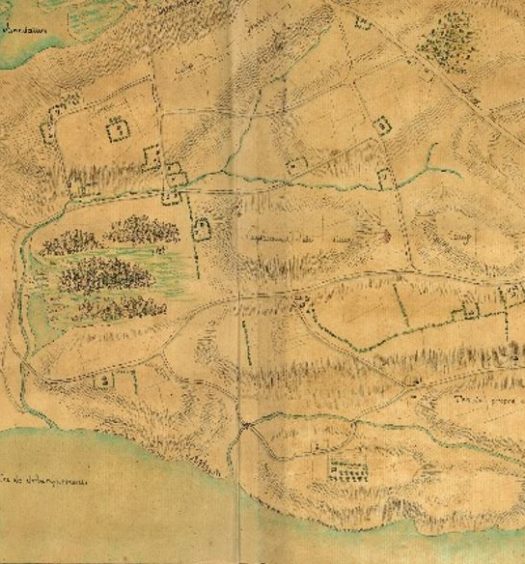

The duel with Lauberdière was fought with swords on June 10, 1781. The site initially selected was too close to the guards, so another location was chosen. The army changed the guards daily at three sites. They posted a sergeant’s guard (a sergeant, corporal and twelve men at two sites: the landing site at Wood’s Castle (now Sachuest Point, about five miles from the camp), and the hospital in the Baptist Church (no longer standing, it then stood at the corner of Barney and Spring streets). In addition, a captain’s guard (a captain, a lieutenant and 90 men) was posted around the camp, which then extended south of the current Newport Public Library to the Cliff Walk near Easton’s Beach.[9]

The duel was likely fought about half a mile or more south of the camp (around where Ruggles Avenue is today or even farther south), as this area was uninhabited in 1781 and would be sufficiently far from the three outposts to avoid the guard interfering with their plans.

There is no description of the duel, but it is known that Lauberdière was slightly wounded in two places, and that he stabbed du Bouchet several times and inflicted a serious chest wound. “Only the clavicle bone stopped his weapon” from causing more damage. Mr. de Mauduit had to assist Lauberdière in withdrawing his sword from du Bouchet’s body.

Lauberdière’s second brought him a horse after the engagement, but du Bouchet had neglected to make any such arrangements. De Mauduit wrapped du Bouchet in a greatcoat as they walked back to Newport. Du Bouchet lost a great quantity of blood along the way but made a good appearance. He encountered many people who greeted him but apparently they did not notice he was wounded and covered in blood.

After bringing du Bouchet to his lodging at Captain Zebadiah Story’s house on Thames Street,[10] de Mauduit made great haste to alert Mr. Robillard,[11] the chief surgeon. Meanwhile du Bouchet tried to stop the effusive bleeding. He felt faint and found himself very ill at ease and feared not being able to stop the blood.

Miss Betsy Story,[12] the daughter of his host, invited du Bouchet to join the family for tea. Very impatient to get to his room, he very imprudently promised to do so, not wanting to prolong the conversation on the stairway. As he delayed too long to keep his promise, Miss Betsy went to remind him. She entered his room and found him without a coat and with a bloodied shirt, dabbing his wound.

This sight filled her with such fear and horror that she let out a loud scream and fainted. The cry and noise of her fall suddenly drew the attention of her father and mother lodged below. They rushed upstairs to find du Bouchet pouring water on Betsy’s face, trying to revive her. But everything seemed useless, as nothing revived her. Her parents were in despair. When the surgeon arrived, he first took care of her and revived her.

Dr. Robillard prescribed du Bouchet to keep a very strict diet, and to maintain a very strict silence. Following the doctor’s orders and because of his good constitution, du Bouchet was on his feet again after seventeen days, even though his wound had been serious. Fortunately, none of the wounds became infected.

Lauberdière had recovered earlier and left Newport on June 23. However, his wound forced him to remain behind in Newport several days, while his division departed without him.

Word of the duel spread in the army, despite attempts to conceal it. Before June 23, Lieutenant General de Choisy invited Du Bouchet and Lauberdière to dine with him, undoubtedly to bring about their reconciliation. Du Bouchet apologized for his conduct and the two settled their differences.[13]

Du Bouchet remained in Newport until the detachment was summoned to bring the fleet and the siege artillery south. His duties of brigade major must have been performed by one of the other two brigade majors during his recovery: either François Louis Thibault, comte de Ménonville (1740-1816) or Jean Josse de Tarlé (1739-1813).[14]

Lauberdière was unable to perform his duties. He was one five aides[15] to Pierre François de Béville (1721-1798), the Quartermaster General of the Army. As an assistant quartermaster general, he should have been involved with reconnoitering and laying out the camps along the route of march, and he was supposed to leave Newport with the main part of the army, but his wound made him unable to do so.

Which one of the assistant quartermasters generals laid out the camps? It does not appear that Béville or Vauban kept diaries and the matter is not clear from other French sources.

The comte de Lauberdière and Mathieu Dumas are the only two French assistant quartermasters general to have kept any account of their work and travels during the march. The two volume English version of Dumas’s journal, Memoirs of his Own Time; Including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration,[16] contains excerpts of his three volume Souvenirs du Lieutenant-Général Cte Mathieu Dumas, de 1770 À 1836.[17] The Memoirs has a 98-page chapter (as opposed to 137 pages in the French version) on the War of American Independence which reviews the main points of the war, but it only includes a few paragraphs about Dumas’s quartermaster activities (pp. 52-53, 55, 61). To get a better picture of his duties as assistant quartermaster general, one should consult La Marche sur Yorktown: Le Journal de Mathieu Dumas (16 Juin – 6 Octobre 1781) [The March to Yorktown: The Journal of Mathieu Dumas (June 16 to October 6, 1781)[18]] transcribed by Bertrand Van Ruymbeke and Iris de Rode. The very first page specifies that “This book will be filled with my business and my thoughts.”

Dumas departed Providence, Rhode Island, on June 17, a day before the first division left Newport. He went directly to Bolton, Connecticut, the site of camp five, where he arrived on the 19th. The Count de Lauberdière departed on June 23, five days after the first division set out and two days behind the last division. He caught up with his division (Bourbonnais) on June 28 at Newtown, Connecticut, the site of camp 10. Thus, he was not able to reconnoiter and plan the first 10 camps. However, both men did make detailed notes and remarks about the places along the route of march and the people they met.

Claude Blanchard (1742–1802), Commissioner of War, departed on June 16. He was at Hartford, Connecticut on the 18th, the day the first division marched out of Newport. His journal[19] seems to indicate that the initial camps had already been reconnoitered and laid out, but we don’t have any indication of who performed these tasks.

Each division had an assistant quartermaster general assigned to it. The first division (Bourbonnais) had Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau (1755-1813). The second division (Royal Deux Ponts) had Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, comte de Lameth. The third division (Soissonnais) had George Henri Victor Collot (1750-1805) and the fourth division had Louis Alexandre Berthier.[20] Although Berthier was assigned to the quartermaster corps and accompanied the fourth division, his main duties were to map the route of march and the camps.[21]

So, the task of reconnoitering and planning the first camps must have fallen to Pierre François de Béville, Quartermaster General of the Army; Jacques Anne Joseph le Prestre, comte de Vauban; or Hans Axel, comte de Fersen. As noted above, Béville and Vauban apparently did not keep journals and Fersen acknowledges that he was so busy during the period of the march that he had no time to write. This may indicate that Fersen reconnoitered the early camps and worked with Dumas for the others. Dumas’s journal seems to indicate that he and Berthier were the only ones who reconnoitered after the encampment at the Odell house in Greenburgh, New York.[22]

Dumas and Lauberdière remained with their respective divisions as far as Head of Elk (Elkton, Maryland). From there, they took different routes to cross the Susquehanna River to Bushtown (Harford, Maryland). After leaving Head of Elk, Lauberdière and the left column crossed the Susquehanna River at Lower Ferry (now known as Havre de Grace, Maryland). The right column, composed of all of Lauzun’s Legion, the artillery and the baggage, crossed at the ford of Bald Friar’s Ferry. This added a day’s march (about twenty miles) to the voyage, and the crossing presented many difficulties. Dumas was surprised that no serious accidents occurred to delay them from rejoining the left column at Bushtown. He provides all the details in his journal.

When the troops arrived at Annapolis, they found Admiral Jacques-Melchior Saint-Laurent, Comte de Barras’s (1719–1793) fleet and General de Choisy’s detachment there waiting for them with the siege artillery. The French troops boarded the ships at Annapolis and sailed to Williamsburg, Virginia, where they joined with Major General Marie Jean Paul Joseph du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) and his army and General George Washington’s (1732–1799) Continental Army prior to marching to Yorktown. The stage for laying siege to and capturing a British army at Yorktown was in place.

Appendix 1

Dueling Rules—The Code Duello

A committee of Irishmen drew up the dueling code, called the Code Duello, in 1777. It largely replaced earlier codes, including the Flos duellatorum (written in 1410) and Il duello (1550), both Italian dueling codes, as well as the German dueling rules set by the Fechtshulen dueling schools.

The Code Duello eventually was used widely throughout Europe and in what would become the United States and was considered the “official” rules of dueling. In fact, remarkably, the U.S. Navy included the text of the Code Duello in the midshipman’s handbook up until dueling by naval officers was finally banned in 1862.

The French recognized three sorts of offenses:

- First: A simple offense.

- Second: An offense of an insulting nature.

- Third: An offense with personal acts of violence.

The person who felt offended or dishonored had to “demand satisfaction,” which means either a public apology or satisfaction via the conclusion of the duel. This demand was usually done by throwing his glove down in front of the person who offended the challenger or by hitting him in the face with a glove. Each person had to then find a person to be his “second” who would be responsible for assuring the duel was conducted honorably. The seconds chose a place to duel and decided whether or not the weapons were equal.

The person who declared the duel got to choose when the duel would be finished. Common endings to duels were:

- until one person was injured, even if the injury was minor

- until one person could no longer fight because he was too hurt

- until one person was killed or injured so badly that he would soon die

- duels with pistols could be ended after the first shot, even if no one was hit. Most pistol duels did not go longer than 3 shots.

The challenged person had the choice of an apology or other restitution or choosing the weapons for the duel. The challenger would then propose a place for the “field of honor.” The challenged person either accepted the site or proposed an alternative. The location had to be a place where the opponents could duel without being arrested. It was common for the constables to set aside such places and times and spread the information, so honest people could avoid unpatrolled places.

The statue of General Rochambeau at King’s Park in Newport near Fort Adams. The author, part of a group of French Army reenactors for American Revolutionary War reenactments, stands in the second row under Rochambeau’s left foot (Norman Desmarais)

As most duels were conducted when one man offended another’s honor, an apology on the part of the challenged could avert a bloody duel if delivered properly. So, a proper apology would logically help solve the problem, even once the duel had already begun. The Code Duello dictates a complex method of deciding who should apologize first:

Rule 1: If, in the course of a discussion, an offense is offered, the person who has been offended is the injured party. If this injury is followed by a blow, unquestionably the party who has been struck is the injured one. To return one blow by another of a more serious nature severely wounding, for instance, after a slap in the face does not constitute the person who received the second blow, however severe it may have been, the party originally insulted. In this case, satisfaction may be demanded by the party that was first struck. Such a case must be referred to the chances of a meeting.

In other words, the first offense requires the first apology, though the retort may have been more offensive than the insult. For example, A tells B he is impertinent, etc. B retorts that he lies; yet A must make the first apology because he gave the first offense. B may then explain away the retort by a subsequent apology.

Rule 2: If an insult follows an impolite expression, if the aggressor considers himself offended, or if the person who has received the insult considers himself insulted, the case must also be referred to a meeting.

Rule 3: If, in the course of a discussion, during which the rules of politeness have not been transgressed, but in consequence of which, expressions have been made use of which induce one of the party to consider himself offended, the man who demands satisfaction cannot be considered the aggressor, or the person who gives it the offender. This case must be submitted to the trial of chance.

Rule 4: But if a man sends a message without a sufficient cause, in this case he becomes the aggressor; and the seconds, before they allow a meeting to take place, must insist upon a sufficient reason being manifestly shown.

The rules also dictate when an apology can be accepted, thus preventing the duel, and when no verbal apology will be sufficient:

Rule 5: As a blow is strictly prohibited under any circumstances among gentlemen, no verbal apology can be received for such an insult. The alternatives, therefore — the offender handing a cane to the injured party, to be used on his own back, at the same time begging pardon; firing on until one or both are disabled; or exchanging three shots, and then asking pardon without proffer of the cane ….

Rule 6: There are offenses of such a galling nature, that they may lead the insulted party to have recourse to acts of violence. Such acts ought invariably to be avoided, as they can only tend to mortal combat.

Rule 7: The offended party has the choice of arms. (This is a point of such vital importance, that it is impossible to be too careful in ascertaining, coolly and deliberately, from which of the parties the insult originated. To name a duel, refers to time and place.)

Rule 8: When the offense has been of a degrading nature, the offended has the right to name both the arms and the duel.

Rule 9: When the offense has been attended by acts of violence, the offended party has the right to name his duel, his arms, the distance, and may insist upon the aggressor not using his own arms, to which he may have become accustomed by practice; but in this case the offended party must also use weapons in which he is not practiced.

Rule 10: There are only three legal arms; the sword, the saber, the pistol. The saber may be refused even by the aggressor, especially if he is a retired officer; but it may be always objected to by a civilian.

A rendering by a French artist of the end of a duel held in France, apparently on the banks of the Seine River (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Dueling Etiquette

A duel is a controlled battle between gentlemen of honor, not a brawl. As such, a certain level of dignity was expected of all participants. Rule 13 describes dignified dueling behavior. It is also one that was frequently broken, since many duelists did not really want to die, kill or maim. They only wanted to defend their honor.

Rule 13 states:

No dumb shooting or firing in the air is admissible in any case. The challenger ought not to have challenged without receiving offense; and the challenged ought, if he gave offense, to have made an apology before he came on the ground; therefore, children’s play must be dishonorable on one side or the other and is accordingly prohibited.

Since the holding of the duel itself would usually be enough to satisfy honor, duelists might use dummy bullets, or declare ahead of time that they would fire their weapon into the air or at a non-vital area of their opponent’s body. This tactic is called deloping, (from the French “delope,” meaning “to throw away“). The Code Duello frowned on this. The reasoning behind this rule is to reinforce that dueling is not a game; in issuing a challenge for a duel, and in accepting a challenge, each participant is declaring that they are prepared to shoot and be shot at.

Rule 15 states:

Challenges are never to be delivered at night, unless the party to be challenged intend leaving the place of offense before morning; for it is desirable to avoid all hot-headed proceedings.

There are no rules pertaining to what time duels can take place. The Code encourages duelists to sleep on their wounded pride and then duel with a calm demeanor the next day. In other words, men should avoid getting drunk and combative and sloppily issuing or accepting duel challenges that they would regret in the morning. Dueling at or before sunrise was more a strategy for avoiding interruptions from the public or intervention from the authorities.

Like dueling at dawn, leaving a farewell note for families and otherwise getting affairs in order was more of a practical tradition than an actual rule. Though many duels ended without bloodshed or with only minor injuries, the principle of the duel is that both participants go in prepared to die for their honor.

Rule 16: The challenged has the right to choose his own weapon, unless the challenger gives his honor he is no swordsman; after which, however, he can decline any second species of weapon proposed by the challenged.

Rule 17: The challenger chooses the distance and the challenged chooses the ground. There was variety in the distance. Some duels were fought at twelve paces, and some at fourteen or fifteen. The challenger chose the exact distance. Though it was common to wait for the signal cry of “fire!” before shooting, the Code Duello states that firing can also be done at the parties’ “reasonable leisure” if they agree to that beforehand. Even if given a signal, opponents didn’t always fire immediately.

Perhaps one of the most important rules of dueling does not involve the mechanics of the duel itself, but rather who is allowed to duel. In medieval Europe, dueling was the sport of noble-born men. Although commoners did fight and certainly did face each other in contests that could be called duels, an actual, honor-bound duel had to be conducted between two men of noble rank. One reason for this was economic — swords were expensive weapons, and not every peasant had one. But it was also a means of distinguishing the upper and lower classes. Many countries had laws forbidding commoners to fight amongst themselves, while dukes, princes and even kings were expected to duel each other.

Seconds

A cornerstone of dueling is the second, who is required to be of equal rank to their principal (meaning a nobleman couldn’t just force one of his servants to be his second). The role of the seconds is spelled out in several rules.

The seconds negotiated terms with the opponent’s seconds, bore witness to the duel, and, if necessary, stepped in and took part in the duel themselves. The seconds also arranged the time and the terms of the duel during their negotiations.

Rule 18: The seconds load in presence of each other, unless they give their mutual honors they have charged smooth and single, which should be held sufficient. (Note the reference to smooth-bored pistols as opposed to rifled weapons.)

Rule 19: Firing may be regulated — first by signal; secondly, by word of command; or thirdly, at pleasure — as may be agreeable to the parties. In the latter case, the parties may fire at their reasonable leisure, but second presents and rests are strictly prohibited.

Rule 21: Even if there’s little chance of reconciliation, seconds are obliged to meet and negotiate to attempt a reconciliation before the duel takes place, or after sufficient firing or hits, as specified. If attempts at reconciliation fail, the next step for the seconds is to sort out the rules of engagement. The Code Duello acknowledges that the seconds might get involved in the fight themselves and specifies how this involvement might occur.

Rule 25: Where seconds disagree and resolve to exchange shots themselves, it must be at the same time and at right angles with their principals.

When a Duel is Over

Dueling is about recovering honor, not about killing. So dueling “to the death” is not considered desirable in the Code Duello, although this may have been the ultimate end to many duels.

Rule 5 states in part, “If swords are used, the parties engage until one is well blooded, disabled, or disarmed; or until, after receiving a wound, and blood being drawn, the aggressor begs pardon.”

Rule 22 further specified that any wound sufficient to agitate the nerves and necessarily make the hand shake, must end the business for that day.

The sword, with or without a companion weapon, was the customary dueling weapon until around 1800. The custom of wearing the sword in civilian life had largely died out about that time and the pistol had taken its place in both dueling and self-defense. Nevertheless, sword duels continued until the extinction of dueling itself.

When using swords, the two parties would start on opposite sides of a square twenty paces wide. The square was usually marked at the corners with dropped handkerchiefs. Leaving the square was considered cowardice.

If one party failed to appear, he was considered to be a coward and the appearing party would win by default. The seconds (and sometimes the doctor) would bear witness to the cowardice. The resulting reputation for cowardice would often affect the individual’s standing in society considerably, perhaps even extending to their family.

Notes

[1] Bishop, Morris, The Exotics: Being a Collection of Unique Personalities and Remarkable Characters (American Heritage Press, 1969), p. 74. [2] The last duel in France was fought on April 21, 1967 when Gaullist Deputy René Ribière challenged the socialist Mayor Gaston Defferre to a duel for calling him ”idiot” during a debate at the National Assembly. The duel, with swords as the weapons, was fought at a secret place at Neuilly in the western suburbs of Paris early in the morning. René Ribière was slightly wounded. [3] Lauberdière was 21 when he came to America and 22 at the time of the duel. [4] The Count de Lauberdière’s diary is at the Bibliothèque Nationale and available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52506900t/f17.image. I translated it into English. See Lauberdière Louis François Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevoye, The Road to Yorktown: The French Campaigns in the American Revolution, 1780-1783, Edited and translated by Norman Desmarais (Savas Beatie, 2020). [5] Journal d’un emigré; ou cahiers d’un etudiant en philosophie, qui a commencé son cours, dès son entrée dans le Monde (Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library), pp. 214-224. [6] Brigadier General Claude Gabriel marquis de Choisy (1723-1800) commanded Lauzun’s Legion at the siege of Yorktown. Benjamin Franklin presented him with the Libertas Americana medal for his service in America. [7] Thomas-Antoine de Mauduit du Plessis (1753–1791) was a lieutenant of artillery who distinguished himself at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown and Monmouth, which gained him a promotion to rank of lieutenant colonel. He was also instrumental in the defense of Fort Mercer where Major General Count Karl Emil Kurt von Donop (1740–1777) lost his life. [8] Journal d’un emigré, p. 38. [9] Rochambeau, Donatien Marie Joseph de Vimeur, Armee de Rochambeau: Livre d’ordres contenant ceux donner depuis le débarquement des troupes a Newport en Amerique, Septentrionale, 1780, Archives Departementales de Meurthe et Moselle, E 235. [10] The house, located at 265 Thames Street, no longer exists. Communication with Dr. Robert Selig, Nov. 15, 2021. [11] The house, located at 265 Thames Street, no longer exists. Communication with Dr. Robert Selig, Nov. 15, 2021. [12] Betsy married Joseph Conckling of Connecticut around February 1785. [13] The detachment left at Newport under the orders of Brigadier General de Choisy. The detachment embarked in August aboard the Count de Barras’s fleet which brought the soldiers and artillery train to Annapolis, Maryland, to rejoin the rest of the army before the army proceeded to Yorktown, Virginia. [14] Ménonville resided with “Captain George” at 90 Spring Street. Tarlé and his brother Benoît de Tarlé lodged in the home of Charles Tillinghast. Communication with Dr. Robert Selig, Nov. 15, 2021. [15] The others were Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, comte de Lameth (1760-1829), Jacques Anne Joseph le Prestre, comte de Vauban (1754-1815), Hans Axel von, comte de Fersen (1755-1810) and Mathieu Dumas (1753-1837). [16] Memoirs of his Own Time; Including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration, by Lieut.-Gen. Count Mathieu Dumas. (London: Richard Bentley, 1839). [17] Souvenirs du Lieutenant-Général Cte Mathieu Dumas, de 1770 à 1836 (C. Gosselin, 1839). [18] Dumas, Mathieu, La Marche sur Yorktown: Le Journal de Mathieu Dumas (16 Juin-6 Octobre 1781): Sur les Traces de L’indépendance des Etats-Unis, edited by Bertrand Van Ruymbeke and Iris de Rode (Jean-Jacques Wuillaume, 2018). [19] Blanchard, Claude, The Journal of Claude Blanchard, Commissary of the French Auxiliary Army sent to the United States during the American Revolution, translated and edited by Thomas Balch (Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1876) (Eyewitness Accounts of the American Revolution). [New York]: New York Times; Arno Press, 1969). [20] See Berthier’s journal in Rice, Howard C. Jr. and Anne S.K. Brown, The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 (Princeton: Princeton University Press and Providence: Brown University Press, 1972, Vol. 1, pp. 246-247. [21] Ibid., Vol. 2. [22] Selig, Robert A, The Franco-American Encampment in the Town of Greenburgh, 6 July – 18 August 1781: A Historical Overview and Resource Inventory (Town of Greenburgh, NY, 2020.