[From the editor: This charming article displays the author’s wonderful humor and eye for detail. Its author, Rachel Chase Boynton, was born in December 1894, the daughter of Captain Halsey Chase, the founder and long-time operator of the Prudence Island-Bristol ferry, and Lizzie Kelly Studley. Rachel attended school in a one-room schoolhouse on Prudence Island, where she was taught by her father in elementary school. She later became a school teacher, first on Prudence Island, and then on the Rhode Island mainland, including in Providence Public Schools and in Lincoln. Despite her lack of a college degree, she worked as a teacher for more than thirty years. After she married Oliver Griswold Boynton in June 1930 at St. Michaels Church in Bristol, the couple moved to Providence. She also wrote articles for Woman’s Day magazine. Rachel passed away in 1987 at the age of ninety-two. She was the twin sister of Rebecca Chase Herreshoff, whose life was highlighted in an article by Johna Spencer. A prior (also wonderful) article by Rachel Chase Boynton and her upbringing on Prudence Island was previously published on this site. To find both articles, simply click on the Archives tab and then type in Boynton in the search box. Thank you to Daniel Chase Boynton, one of Rachel’s children, and Johna Spencer, for the information in this paragraph. The following story appeared in the Rhode Island Yearbook for 1972.]

I read in the papers about the acute shortage of teachers, it takes me back to my early experiences in that profession. I’m not boasting when I say that I was a successful teacher for thirty years, and yet I have no degree of any kind. I even had the governor of our state, the Hon. John H. Chafee, who is now the Secretary of the Navy, as a student when he was nine years old, and I’m mighty proud of that.

I lived on Prudence Island in the middle of Narragansett Bay, and being the “ugly duckling” of the family, I was elected at the age of 12 (after my mother’s death) to stay home and take care of my baby brothers while my sisters went away to boarding school.

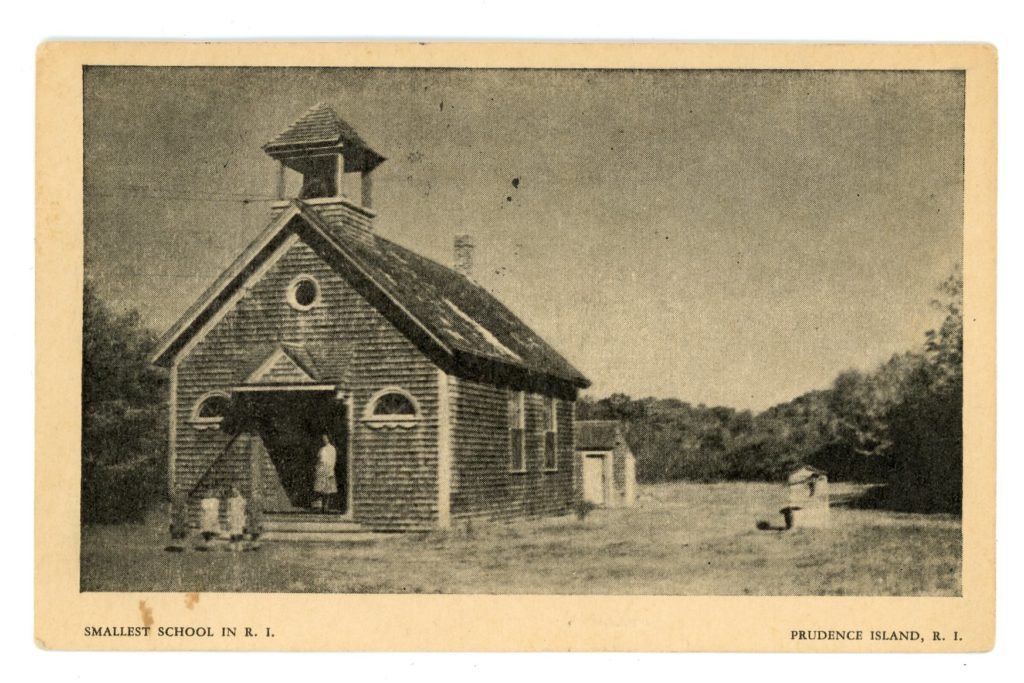

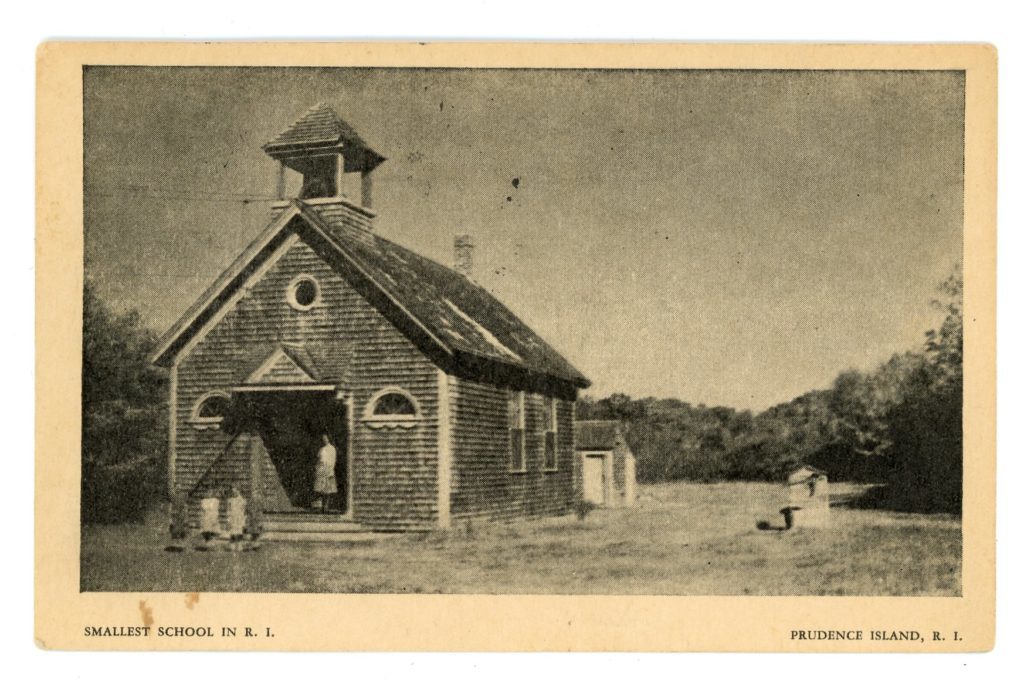

A one-room schoolhouse on Prudence Island, possibly where Rachel Chase Boynton went to school and taught (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)x

After two year of high school, I was obliged to go to work. Apparently in those days, ability and inclination meant something. When I found that I could take an examination for a teacher’s certificate, I studied all night and passed it successfully.

My first position was on the island where I was born, and at the island school built by my father and where he was my teacher all through the elementary grades. By the way, this little island school had a library which included all the classics which had been given by Mr. Collier of COLLIER’S magazine to all schools included in the Town of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. As my father had a literary mind, he encouraged us to read most of the classics before we were fourteen years old.

While teaching for three years at this island school, I lived with an aunt and walked four miles a day. If I thought I was going to be late, I would run the last mile because I wanted to set a good example for my pupils. However, the walk was fun, for it wasn’t uncommon to see seven wild deer in a wooded field. They would stare at me for a while and then go bounding over a stone wall, their white tails flashing in the sunlight. In winter the walk was more difficult because I had to wear long rubber boots trudging through the snow.

There was no janitor service at the school, so that I had to stoke the potbellied stove with coal, piling it on at night so that it would last until morning with the ‘door open. My father had taught me that any task, no matter how menial, should be done to the best of one’s ability, so that I put as much thought into the care of that stove as I did into teaching my twelve pupils in this ungraded school.

In the winter, we would make a huge beef stew on Monday with every child bringing some vegetable while I supplied the meat. In the midst of a math lesson, I might say, “Mary, will you peel the carrots for the stew?” By keeping it in the cold entry, it would last about four days providing a hot dish for each student. There were no disciplinary problems.

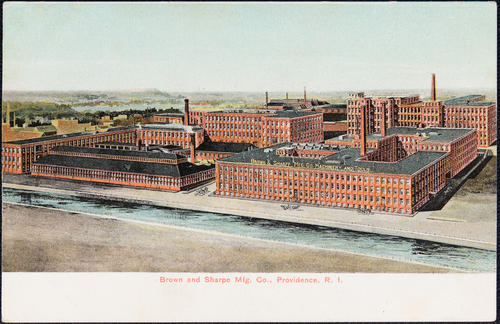

On Saturdays I travelled to Providence on the old bay boat, the City of Newport, to attend classes in school law, methods and management at the old Rhode Island Normal School. During the winter of 1918 the bay was frozen over, so that I walked across the ice from the north end of the island to Warwick Neck in order to take the train to Providence. It was an unforgettable experience for salt water ice often cracks and snaps menacingly.

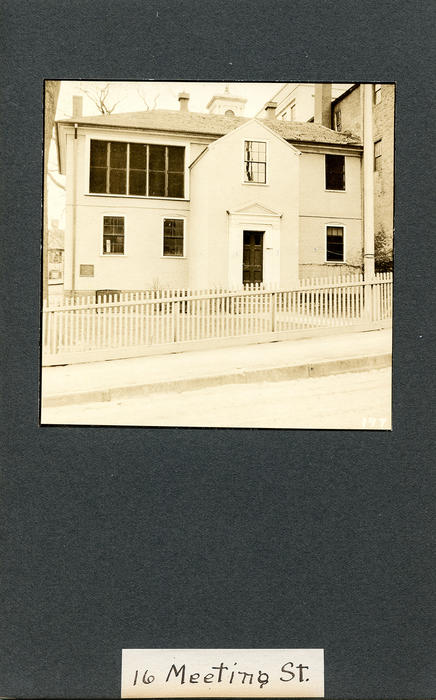

Meeting Street School, also known as the Brick School House at 24 Meeting Street (misidentified as 16 Meeting Street), and later the location of the Providence Preservation Society. The door is framed by pilasters supporting a pediment above the door. A picket fence encloses the yard of the building (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

After three years on the island, I accepted a position in Washington Village in South County where I had fifty children in one room and the first three elementary grades. While I was there, I found out that I could apply for “city training” (under a critic teacher) which is the last six months of the normal school course. Two assistant- superintendents came to visit my class and then I had to interview five men on the school committee. One of those men, a Mr. Reynolds, appointed me. When I went back to thank him, he said, “It’s not very often that you find an honest to goodness Yankee that’s as anxious to teach school as you are.”

After my training I spent three years at the Knight Street School on Federal Hill. Apparently I was good enough to be put on the visiting list; for teachers came nearly every day to observe my teaching methods, yet I couldn’t get a job in that same area now (even if I were young enough) because I haven’t a Bachelor’s Degree. My past experience would mean nothing.

I didn’t stop learning, for there were always evening extension courses at Brown University that were interesting; I also went to Hyannis Summer School.

It was at the Gordon School, a private co-educational school, where I taught Halsey Howe, who is now the rector –of our Episcopal Church. Halsey had an exceptional vocabulary for his age. We had a vocabulary tree on which my pupils put any new words that they had learned. One day we came upon a very difficult word in social studies, whereupon I turned to nine-year-old Halsey and said, “Surely you know the meaning of this–word.” His reply was, “No, Miss Chase, that’s a sticker; it defies analysis.”

When my husband and I had three sons in prep school and college at once in 1948, I wanted to go back to teaching. As I accepted a position at the Lincoln School for girls, in Providence, I announced to Miss Cole, the head mistress, that I had no degrees. Her reply was, “That’s all right! I think more of personality and ability than I do of degrees.”

What’s wrong with our system today that native ability and the will to work has lost some of its importance? I think a degree is a fine thing to have and I wish that I had one; but there are many failures among people who have degrees. Let’s give those eager young people a chance to prove their ability by hard work.

Recently an old pupil of mine came to me for guidance in getting a teaching position in Providence. Because she had attended a junior college and didn’t have a Bachelor’s Degree, she couldn’t qualify for the Rhode Island schools; yet she loves children, and I’m certain that she would make a fine teacher. What she lacks could be made up by taking extension courses if they would give her a chance.

Since teaching has been one of my most rewarding experiences, I am grateful that I was able to accomplish it successfully by hard work and perseverance.

[Banner image: A one-room schoolhouse on Prudence Island, possibly where Rachel Chase Boynton went to school and taught (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]