[Note from the Editor: The following is a town-by-town review of the impact of the destructive Hurricane of 1938. It was written by writers hired by the Federal government in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression to write histories of the New England states. A number of them were in Rhode Island at the time of the storm. They quickly put this book on the Hurricane of 1938 together and released it before the end of 1938. The book they produced was mostly photographs, only a few of which are included here. The write-up for each town covered has one or nuggets in it. Tragedies are told of incidents where multiple deaths occurred in Jamestown, Tiverton, and Providence. However, not every town or tragedy is covered. South County, including the tragedy at Napatree Point, is not covered. Towns covered in detail include Providence, Newport, Bristol, and Woonsocket. Other towns discussed are East Providence, Warren, Prudence Island, Pawtucket, Barrington, Tiverton, and Jamestown. The book is titled, New England Hurricane, A Factual, Pictorial Record (Boston, MA: Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1938). It is available in many of the state’s libraries. I reviewed a copy in the Rhode Island Room at the Peace Dale Library.]

Winds of gale force-60 miles an hour have often struck PROVIDENCE at the autumnal equinox. Everybody minimized the strong wind that was already becoming violent by two o’clock in the afternoon. At five, when most of the offices let out and workers and shoppers started homeward, flying pieces of roof and other heavy objects caused little consternation. Even the most timorous had a tacit faith that the river would not overflow. The last great flood, in 1815, was too remote in history to be a reminder.

But earlier in the day the tide had not receded as it should have. The wind down the Bay had been so strong that it kept the water at almost high tide level, so that when the next high was due, Providence had a double tide, precisely as in 1815. The city was not built for that contingency. No man-made bank of the river nor wharf nor shoring was prepared for an extra rise of more than 10 feet.

Two women and a man struggle in the rising waters of downtown Providence. Many were swept off their feet by rushing water and saved by ropes thrown out of windows.

The lower part of Providence got the flood first. The rising of the water took the same direction as the wind. Down at Field’s Point, about three miles south of the center, the water rushed in, taking possession of a large lumber-yard, carrying thousands of boards along with the tide to deposit them at Point Street Bridge, which acted as a kind of net.

North of Field’s Point lie the headquarters of several oil and coal corporations, with large plants covering many acres of low ground. The waters attacked, surging into basements, pushing aside tank cars, playing with automobiles, and roaring on northward, carrying everything not fastened to the ground.

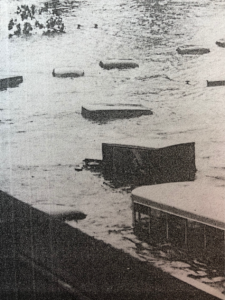

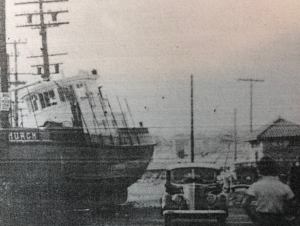

At the Point Street Bridge, the Field’s Point lumber was piled high. Beside it, on the raised ground of South Water Street, lay two coal barges borne down the river by the flood.

The neat row of parked cars in the background bears witness to the impetuosity of the rising water, which gave few car owners a chance to rescue their property and get to high ground.

Crawford Street Bridge, near the center of the city, rises above any southward points. It is part of a very wide structure, known generally as the Weybosset Bridge, shaped like two H’s lying tandem on their side. Its height delayed the flood in the center of town for a few minutes. Once the water got over the bridge, however, it rushed back on Dyer Street to join with waters already there. Meanwhile, near the railroad station where the Woonasquatucket and Moshassuck join, river water poured in from the other direction. The flood gave little warning. Water was filling the streets up to the curbs. There was another lift to the river. All the little alleys and narrow back streets intensified the ferocity of the current. After the second surge, people who braved the waist-high depth were swung off their feet and carried wherever the water happened to be rushing. A couple standing near the Gulf Station at Crawford Street bridge were dragged a block and then hurtled around- a corner down Custom House Street. Like many others they were saved by ropes thrown out of windows.

Down at Field’s Point, about three miles south of the center, the water rushed in, taking possession of a large lumber-yard, carrying thousands of boards along with the tide to deposit them at Point Street Bridge, which acted as a kind of net

Luckily for thousands waiting to go home, the street car terminals were near public buildings, which offered a refuge. The current for trolleys was turned off shortly after five o’clock. Busses continued to operate until the rising waters forced passengers and drivers to abandon them. A United Electric Railways bus was stranded in the middle of Fountain Street. An Express Company truck behind it, like others in the area, was swiftly deserted. The neat row of parked cars in the background bears witness to the impetuosity of the rising water, which gave few car owners a chance to rescue their property and get to high ground.

The din of short-circuited horns in thousands of similarly flooded cars was more clamorous and insistent than any New Year’s Eve celebration.

Craft of every description landed on the streets of Barrington. A yacht in the Barrington River was spared when it ascended the slip and rested there snugly while other vessels were dashed to bits

The sidewalk in the background, behind the soldier safe on his rock pedestal, leads to the Union Station, which served as a refuge and hospital for hundreds of people that night. During the flood the wind often blew more than zoo miles per hour.

The water receded almost as quickly as it had risen. By 10 o’clock the marooned citizens ventured out into the streets from their temporary shelters and started to walk home over the fallen trees and other debris that made auto transportation impossible.

Next morning the main streets were macabre with dark cavities of flooded and shattered first floors. But restoration work had- already begun. The streets were flooded again, this time by pumps gushing with water sucked from basements. Restaurant workers and store clerks, in their shabbiest get-ups, some of them wearing improvised hygienic masks, worked courageously at the seemingly hopeless job of cleaning Providence.

There was a spontaneous mobilization of the National Guard, which began police duty before the water had subsided.

The next morning, WPA workers were enlisted and transported in trucks to the worst-hit areas in the southern part of the State.

A six-story brick wall had fallen in a public parking lot, killing two women in one of the cars and seriously injuring a child.

Abandoned street cars and auto mobiles filled the downtown area. The running board of one automobile served as a shelf for a homely salt-cellar, which must have floated at least two blocks from the nearest restaurant.

Coyle, State Administrator, set up a cot in his office; for days on end he did not leave his post. Red Cross field workers had arrived and emergency work immediately began. Bus service had begun even before the rowboat was removed from Exchange Place.

The animals in Roger Williams Park lost their homes but stayed contentedly in the vicinity, knowing nowhere else to go.

Within twenty-four hours after the flood and hurricane, reconstruction work was progressing systematically. Captain Bower, his two barges high and dry on South Water Street, was being widely quoted: “I’ve spent thirty-eight years between Jacksonville and the Bay of Fundy, and I’ve never seen a storm like this one.”

PAWTUCKET was less severely struck than Providence, but the river rose higher than ever before and exceeded the flood level of 1936. Wind damage was heavy. The most spectacular event was the demolition of the steeple on the 70-year-old First Congregational Church. Clock and all, it toppled over into Broadway, Pawtucket’s most traveled thoroughfare.

Any WOONSOCKET citizen will tell you, “We’re getting so used to floods that the mills all have pumps in their basements. We missed this one, but the wind was the worst in the city’s history.”

No part of the city, high or low, was spared. Along Main Street and at Flynn Square pedestrians who sought shelter in doorways saw great panes of glass in store windows bulge in and out from the wind pressure, finally explode with a cannon-like roar; fragments were delivered to the flying wind, which would then scoop out the merchandise and carry it down the street. It was carnival time for boisterous youngsters, who paraded around in women’s hats and other finery; one young fellow made a costume out of a suit of long underdrawers.

The sign in front of Najarian’s fell within a foot of a pedestrian, who looked at it for a moment and then, realizing his narrow escape, leaped into the middle of the street and ran for his life. The devout women of Woonsocket held impromptu prayer meetings in three or four different languages in the buildings where they sought shelter. Patrolman Eugene Mailloux, at Flynn Square, was injured when swept off his feet and hurled against a passing automobile. The Woonsocket Hospital was filled with casualties. There was one death. Until current was restored late that night, treatments were administered by lamplight.

Textile workers were luckily dismissed early from the mills. Within a short time after closing, several of the buildings collapsed.

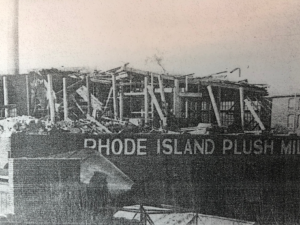

The Rhode Island Plush Mills and the Woonsocket plant of the United Rubber Company were storm-pelted.

The Bell Company and the textile mill of the American Wringer Company were temporarily crippled.

A newly erected chimney on the EAST PROVIDENCE town hall was torn loose and crashed through the slate roof of the building, nearly burying the police radio operator, James F. Byrne. The gas humidor on First Street, one of the familiar landmarks, burst into flames as loosened bricks fell into the tank, causing friction and igniting gas in the outer shell. People on Boston Street, 150 yards away, felt the scorching heat and ran in all directions.

People in Watchemoket Square gasped as they saw Manuel Azevedo leading his docile old horse up the steep flight of iron stairs at the depot end of Boston Street to dry land.

One woman remarked, “I had just the grandest time walking around town, but when I got home and found out what had happened, I fainted. I never would have gone out for a million dollars had I realized.”

Houses formerly fronted with a wide expanse of beach now droop over a cliff, with the waters of the bay lapping at their foundations. At Narragansett Terrace, houses pulled loose from their foundations veered crazily to the side. Steps lead to nowhere. In one, whose interior was exposed, a bathtub stood unmarred. On the sands, a gas range, the skeleton of a small sailboat, and a telephone perched placidly atop a piece of plumbing were strewn about.

Along the shore, acres of property were washed into Narragansett Bay. The former 70-foot beach has more than doubled its width.

Craft of every description landed on the streets of BARRINGTON. The bridge was completely blocked by boats carried there by a capricious tide. A yacht in the Barrington River was spared when it ascended the slip and rested there smugly while other vessels were dashed to bits.

At Bay Springs, houses were washed or blown away with hardly a trace of their former locations. Some dwellings were so expertly twisted off their foundations that nice distinctions between front door and back door could not readily be made. The following morning the gale found residents of Bay Springs dazed, incredulous, philosophical. One man sat in a rocking chair on what bore some resemblance to a back porch, puffed at his pipe, and directed a crew of men sorting out the jigsaw puzzle that was once his home.

Inhabitants of WARREN were astonished to find their main street obstructed by a huge oyster boat, detached from its moorings 200 feet away and deposited in the middle of the thoroughfare. In South Warren seven or eight small houses were washed into the sea.

Six are known to have perished on PRUDENCE ISLAND, off the coast of Bristol. The water ate away the bank up to the lighthouse, but the old guardian of the seas repulsed it. The keeper contrived to escape the tempestuous waters, but his home was thrown into Narragansett Bay.

At BRISTOL, the water rose 15 feet above normal, leaving grotesque spectacles in its wake. Gasoline tanks careened madly through the streets. A rowboat flung through the air alighted on the bar of a saloon. The steeple of the Methodist Church with its 1,000-pound bell somersaulted into the church auditorium. Valuable yachts and lumber were tossed out of Herreshoff’s, who built many of the contenders for the Lipton cup. The wall of the shed was partially ripped off; the structure swayed, then caved in. The Bristol Yacht Club disappeared. William Perry, owner of Bosworth House, oldest residence in Bristol, rushed into his library in an attempt to save records and instruments. The flooring had disappeared and Mr. Perry narrowly escaped drowning in 15 feet of water.

Heartened by the fact that no lives were lost, Bristol zealously set about rehabilitation. WPA workers, aided by other laborers, cleared streets of wreckage, with trucks, tractors, and Diesel-powered shovels. Weakened structures were ripped down. Fire trucks pumped water from cellars. National Guardsmen, police, and volunteers patrolled the streets and prevented looting. Employees of the State Board of Public Health joined forces with the Bristol branch of the Red Cross and the Bristol District Nursing Association. Instructions were posted about public and personal health. Free injections were given against typhoid.

The Bristol Phoenix lived up to newspaper tradition; with presses cut of commission it issued a mimeographed paper.

In the emergency people rose to heroic heights. A lady told, “To my amazement, my nephew, a sea-scout, played an important role, saving two neighbors and performing other useful tasks, when as a rule he was a good-for-nothing.”

The mainland and the northern tip of the Island of Rhode Island are closest at TIVERTON. The converging land made a bottleneck to intensify the northward surge of the water. Houses managed to stand despite the force that disabled the Stone Bridge and scrambled the hundreds of boats, one of which was tossed over a wall.

Many year-round residents lost their lives; motorists travelling the road to Newport or Fall River were terrified. An eye-witness, having deserted his car and taken cover in a nearby house, reported: “There was a Packard on the road with three women and two men in it. When the big wave struck, it must have washed the Packard away, for after the wave had passed I was unable to see either the car or the people who were in it.” The house into which this witness and five others had broken their way in a frantic escape from the rising water was floated out into the river. Two sides were blown off, and other parts began to collapse during the voyage until only the roof, with its six passengers, was left. It finally settled in a tree and the men were rescued by State Police.

On JAMESTOWN, a placid island between Aquidneck and the mainland, long celebrated for its “. . . . modest dwellings scattered wide along the hills and water’s side,” seven school children were trapped in a bus and drowned. The famous old Governor Carr, a revered institution, traveling a ferry lane established early in the State’s, history, now lies grounded—a Gargantuan, embarrassed monument.

Island Park all but vanished under a breaker with a reported height of 30-40 feet. A house that kept its first floor was pierced through by the gush of water. Well-equipped basements, with electric pumps, set-tubs, and washing machines, were completely uncovered. The site of another home was marked by only a couple of boards, a rag, and an overturned milk bottle, still full.

A sailor, trying to fasten a line at the New York Yacht Club slip at Newport, was marooned on a pile

NEWPORT boasts miles of exposed shore line, beaches, fabulous homes, a busy harbor. The beaches were the first struck as waves leaped and reared and tore at the boardwalk on Easton’s Beach. The road offered little resistance and was partially submerged. Up in the harbor the water flowed over the lowlands and wharves closely built up with coal yards, fish markets, lumber yards, ship chandleries, garages, and restaurants. It ripped barges and boats from their moorings and twirled them about aimlessly. Thames Street, narrow, old-fashioned, packed with thriving business establishments, was flooded.

Ferry landings were obscured in a distended and swollen harbor; as the water rose violently a sailor, trying to fasten a line at the New York Yacht Club slip, was marooned on a pile.

The Yacht Placidia held at her dock, but was a pitiful hulk after the wind died down. The hawsers of the Pequannock were slipped off their piles by the height of the tide and the steamer ran amuck across the harbor, demolishing 500 feet of the Torpedo Station breakwater before being blown ashore at Gould Island.

EASTON’S BEACH was recognizable but hopelessly ruined.

THIRD BEACH was swept clean. A fireplace and chimney were outlined against the sky as if prepared for some Druid ceremonial.

Of BAILEY’S BEACH, only the central portion of the bathing pavilion remained, right in the center of the road.

Parts of the Ocean Drive were gnawed away by the sea, and passage was impossible.

On Washington Street the blacksmith and boiler shops of the New England Steamship Company collapsed. The concussion hurled tons of dust and soot into the air, so that a spectator described it as “looking like a typhoon.” Further up the street houses were invaded by the water; rescue workers struggled along in rowboats from door to door, offering transportation to hysterical mothers and children.

By 6:30 the water had returned to its old confines and the wind had eased down. The city was dark. Full devastation could not be estimated until the cool dawn of the next morning.

Buildings judged unsafe were immediately burned or pulled down, lest they crash and inflict further injury to an already devastated area.

Among these late victims was the Pavilion at Easton’s Beach, once famous for shore dinners.

WPA workers and National Guardsmen were summoned by sound truck at midnight, and reclamation was begun. One of the workers answering the call describes his sensation as he threaded his way through streets once proudly lined with trees: “It was like walking through a forest, with its sweetish scent of things green and fresh.”

[Banner Image: Two women and a man struggle in the rising water of downtown Providence. Many were swept off their feet by the rushing water and saved by ropes thrown out of windows.]