Home ownership is a mainstay of the American Dream. In colonial Rhode Island, merchant shippers and merchant retailers, as well as professionals, such as attorneys and physicians, had access and control of income, resources, and property. However, over time seaports, like Newport, saw the increasing wealth for skilled artisans (such as distillers, ropemakers, carpenters, and blacksmiths), mariners, and owners of small businesses, creating a group of individuals with the money to acquire land and homes. Social values such as hard work, frugality, and respectability were key attributes to acquiring property. Such was the prospect before the Revolution commenced, for 53 free—but formerly enslaved—men and women in Newport. In the Rhode Island Colony Census of 1774, they are listed as heads of households, suggesting the possibility that some were homeowners.

My research began with the question, how did those who were formerly enslaved become homeowners in pre- and post-Revolutionary Newport? Where did they settle? As property owners, what rights by law extended to those of African heritage? I build on earlier research of three scholars. In 1998, Richard Youngken identified ten Newport men of African heritage who owned real estate and were both business owners and active in the African American community by the early nineteenth century.[1] Akeia A. F. Benard, in her 2008 dissertation, delved into probate and land evidence, identifying twenty-six property owners among the former enslaved.[2] In 2009, Newport historian James Garman identified early nineteenth century Black homeowners in the New Town neighborhood.[3]

I began with a list of African Union Society members, which over time from the 1780s to 1794, numbered about eighty free men of color. Another list of African Benevolent Society members contains the names of about sixty free men and women who joined the efforts to build a school in 1808 and a church in 1824.[4] Census lists from 1774, 1782, 1790, and 1800, as well as the tax list of 1798, provided additional names. With these lists in hand, the card catalogs at Newport City Hall revealed two dozen landowners. Included in the summaries for each owner are dates of birth and death garnered from newspapers, from records of God’s Little Acre cemetery, or the Stevens Shop gravestone accounts, and Newport Historical Society manuscripts.

Enslavers assigned their surnames to the enslaved and assigned men of African heritage first names of classical origin (e.g., Cato, Scipio), African names (e.g., Yamma, Quam), or geographic locations (e.g., Bristol, Newport, London). Enslaved Newport women sometimes had Roman first names, such as Diana, Flora, or Phoebe, but were often named Phillis, Sarah, Sylvia, or Violet. Deeds in Newport Land Evidence Records record not just the man or woman’s name but their occupation and identify them as free persons of color.

Several patterns emerge. Wills often reveal the inheritance of houses and lots by wives and descendant children, with the first filing of deeds at the time of sale by the wife or descendant family. In some cases, this was twenty, forty, and up to eighty years after the purchase date. For some individuals, no deed was discovered but the Black person was listed as an abutter in another deed. Some original deeds may have been lost in the sinking of a British ship at Hellsgate in 1779, when wet city records were taken and stored for three years in a warehouse.[5] Nevertheless, city documents reveal over sixty individuals of African heritage owning house lots from the 1780s to the 1820s.

Formerly enslaved families lived on lots of substantial size. The survey plots for New Town and Easton’s Point show lot size as 5,000 square feet (fifty feet by one hundred feet). In 1801, the William Handy subdivision survey showed thirty-four lots each 63 feet x 98 feet on Levin/William/Thomas/John Streets, about 6,000 square feet each. With such large plots, families could plant gardens and keep farm animals. Some families bought a large lot and sold parts of it to relatives or friends. [6]

The cost of a home and lot varied. Bacchus Coggeshall paid $52 for his lot in New Town while Arthur Flagg paid $26.50 in Easton’s Point for a lot the same size. When Cudjo Hicks bought two lots in the Handy subdivision, one cost him $30 in 1810 while the other property was $75 in 1800. Robert Keith paid $60 for his house lot on Lower Thames Street, while Abraham Casey paid $300 for his house and lot on Levin Street.

Black men earned a decent, steady income by working in skilled jobs in the maritime trades, like boatbuilding, barrel making, and ropemaking. They also derived income from house construction, chocolate grinding, masonry, furniture making, distilling, and spermaceti candle making.

How Individuals Acquired Property

Building a dwelling or purchasing a house on a lot necessitated financing. Although five banks formed in Newport from 1795 to 1819 and there was no local ordinance or state law prohibiting lending money to Black men or women, there is no record of any loans by these banks to Black men.[7] Nevertheless, at least sixty people of African heritage became homeowners during this period.

In some instances, members of the Free African Union Society offered mortgages to prospective homebuyers. That was the role of Cesar Lyndon (died ca 1794), Bacchus Coggeshall (died 1808), Cato Easton (died 1812), and George Johnson (died 1819).[8]

Another option was to lease a lot from the town of Newport with the option to buy. The area of New Town was in the north, a part of the “School Lands,” which Newport leaders tried to develop by selling or leasing lots from 1763 through 1800. Newport leaders encouraged Black residents to lease property with payment to the town that was often in produce. The size of the lot allowed the residents to work a garden and to use the resource for payment.[9]

A third way was for formerly enslaved people to take out a mortgage on a house from the descendants of a slave owner until they accumulated funds to buy the house and lot. Such was the case with the free Black Thurstons and a house in the Point owned by Rev. Gardner Thurston (1721-1802). According to the 1782 Census, six Black people lived in the house owned by Reverend Thurston on Easton’s Point; they were probably all free since there was no White head of household. Since the minister never owned a slave, they were likely formerly enslaved by the minister’s father, Capt. Edward Thurston. The house and Lot #129, fronted Washington Street on the west and Walnut Street on the south. In 1801 “Flora Thurston, Widow, Newport Thurston, cooper, and Violet Thurston, spinster,” took out a mortgage with the minister before his death.[10]

Another path to ownership was by an arrangement with the owner. Arthur Flagg, Sr. (ca. 1733-1810) lived in a house inherited by Elisabeth Flagg (1751-1827), the daughter of Arthur Flagg’s first enslavers, Mary Ward (1713-1781) and Ebenezer Flagg, ropewalk owner (1710-1762). In the 1782 Rhode Island Census, nine Black people lived in the house owned by Mary Flagg. Those residents were likely Arthur Flagg, Sr., a ropemaker, his wife Flora (1727-1802) and children Violet, Arthur Jr., Solomon Nuba, Rosanna, Peggy, Phoebe, and Abraham. On March 19, 1793, Arthur Flagg, Sr. stated that he was selling a house and lot for $30 to Cupit Brown. Flagg indicated that it was “the same sold by John Ingraham to Mary Flagg, east on Thames Street, south on land of Col. Benjamin Hall, west on the heirs of Nathan Ingraham, north on the heirs of Capt. William Read.” The house and lot were on the west side of lower Thames Street, south of William Ellery abutting Cross Street.[11] There is no land evidence record of a sale to Brown. If Flagg sold the house lot to Brown, it was back in the Flagg family when he wrote his will on March 19, 1804, leaving the house lot to his family. The Flagg family lived there for about eighty years.[12]

How Enclaves Emerged

New Town Neighborhood, the North End of Newport

Reconstruction of the Survey Map of School Lands in Newport, Rhode Island in 1763 by James Garman, “School Lands to Kerry Hill: Two Centuries of Urban Development at the Northern End of Newport, RI” (2009), accessed at https://digitalcommons.Salve.edu. Free men of color owned Lots 5, 17,18, and 24 between 1793 and 1810

New Town in the north end of Newport was an area of leather tanneries, dye houses, a ropewalk, and market gardens. The twelve acres bordered the Gallows Field and the Common Burying Ground. The town encouraged home ownership by charging a minimal annual quitrent for each of the seventy-five house lots. Historian James Garman identified the house lots where Barker, Potter, Coggeshall, Gardner, and Simmons lived. [13] Historian Akeia de Barros Gomes located Bess Brown (1729-1793) who left land to her grandson George Johnson, who died ca. 1820, and wife Phillis (Chaloner), who died in 1798. Lots #17 and #18 were on Spruce Street (now Kingston Avenue).[14] What follows is the results of research by me on other families who lived in New Town. Hampshire, Flagg, Taylor, Ellery, and Weeden families were on Hunt’s Lane (now Caleb Earl Street) or on Green Lane (now Tilden Avenue) near the Quaker Cemetery.

Cato Barker, “a Man of Colour Trader,” sold house lots he owned: Lot #24 in New Town 1807 [LE 10: 307] and another lot in 1808 [LE 10: 321]. Impressively, Cato also owned a hotel and stables on Broadway.

Cesar Potter, “a Man of Colour, Laborer,” owned Lot #5 in New Town, which he sold to Bacchus Coggeshall, “a Free black Man, Chocolate maker” (ca. 1746-1808) and his wife Anne (Deandrease) Coggeshall in 1803. The house still stands at #20 Kingston Avenue [LE 10: 418, NP 4: 526 (1808)]. Anne inherited the house and lot; her niece, Hope (Coggeshall) Simmons inherited the home in 1818 at the death of Anne. Hannah and Ann Gardner, as well as Cesar and his wife, Catherine Potter, occupied 1,000 square feet of the lot [LE 14: 235 (1816)].

Cuff Simmons, who married Hope Coggeshall, was noted in the bounds of the deeds of others in 1810, as owning Lot #5 Spruce Street, New Town [LE 17: 504, which is a deed filed in 1830, twenty-five years later, when Simmons sold the property to chaise makers, Robert, and George Shaw.] In the Newport Mercury in 1811 Cuff Simmons advertised his crew of chimney sweepers, operating his business from the corner of Warner and Tanner Streets.

George and Jenny Hampshire (also Hampshear) owned a house on Hunt’s Lane (now Caleb Earl Street). In 1811, when George’s widow Jenny was deceased, Job Townsend administered an auction of the house and land, fronting 26 feet on Hunt’s Lane and 83 feet deep, a lot of 1407 square feet [NP 4: 254 (1805), NP 5: 26, LE 12: 330].

When Arthur Flagg, Jr. (1764-1827), a “free Man of Colour,” mariner, and his wife Susannah, sold a house and lot in 1807 on Green Lane (now Tilden Avenue), they stated that this was the same property deeded to Arthur Flagg, Sr. by Charles Davenport, a mason, in Dec. 1790 [LE 10: 239].

Rosanna (Flagg) Taylor (1772-1847), “Widow” of Simeon Taylor, lived in a house and lot identified as the same sold to Simeon Taylor by Charles Davenport and his wife Sarah, on Dec. 27, 1798, on Green Lane in New Town [LE vol. 8: 366]. Eliza Flagg (1807-1854), daughter of Arthur Flagg, Jr., affirmed the ownership of Phebe (Flagg) Benson and her daughters Mary Jane Benson Ann Benson (1803-1863) so they could sell in 1857 [NP 34: 51, LE 34: 51].

Showing Green Lane (Tilden Avenue) in Newport, from a larger map by Matthew Dripps (1850). Prepared for The West Broadway Neighborhood, Newport, RI Report (Mar. 1977) by the Rhode Island Historic Preservation Commission, p. 19. On Green Lane (Tilden Avenue), the Flagg families and the Weeden families owned houses on a lot between Stephen Northam and Nicholas White from 1790 to 1852.

Henrietta Ellery (1769-1848), “a free woman of color,” received a deed from Charles Davenport and his wife Sarah to a piece of property in 1801 and was mentioned as an abutter in the Flagg deeds. When Henrietta died, the house and lot were sold at auction by Samuel Vernon in 1850 [LE 28: 138].

James Humphrey Weeden (1769-1852), mariner, and his wife Jane Weeden (1774-1851) in 1842, owned/lived at a property previously owned by Arthur Flagg Jr, with the abutter to the south Henrietta Ellery and the abutter to the north Rosanna Taylor [LE 24: 78]. Their son Christopher inherited the property and sold it to Thomas Brown in 1852 [LE 32: 205]. The bounds of the lot were west on Green Lane (later Tilden Ave) 50 feet, south on land formerly of Henrietta Ellery 90 feet, east on land of Stephen Northam (formerly land of Paul Mumford), and north on Rosanna Taylor 90 feet.

On Tilden Avenue were the homes of the Arthur Flagg, Sr. family, their descendants, and subsequently, the Weeden family. The Flagg-Weeden houses were located between the Stephen Northam House to the southwest which still stands at #79 Tilden and the Nicholas White House at #69 Tilden. Both of those houses were built before 1800. On the Flagg-Weedon lot stand two houses built between 1850-1870.

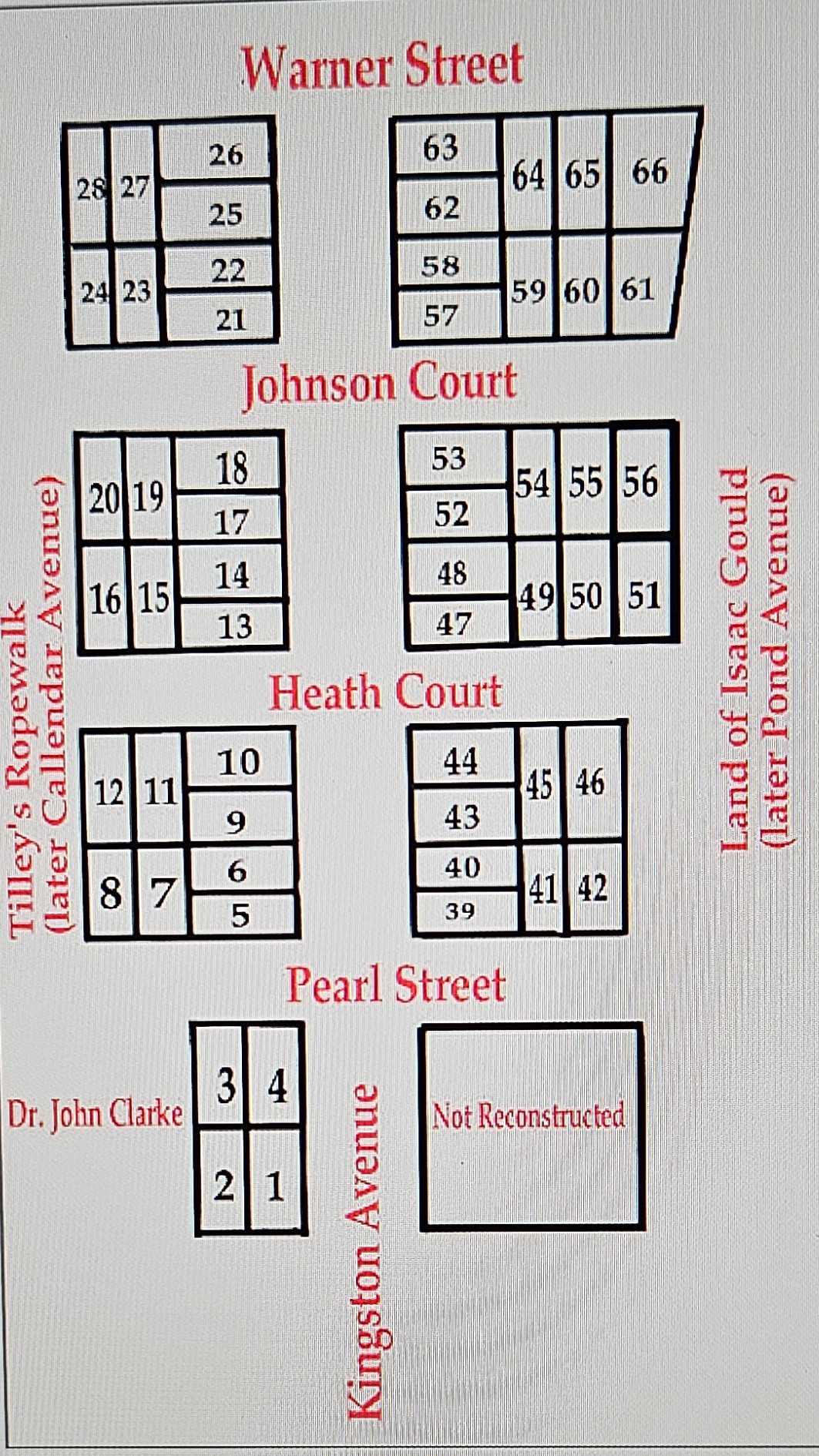

The William Handy Subdivision along Levin, Thomas, John, and William Streets

In central Newport, this subdivision extended to the Thames Street wharves on the harbor and Bellevue Avenue. In 1801, William Handy had the twenty-one acres, inherited by the four brothers, surveyed into thirty-four 6000 sq. ft. lots. [NP: 8: 113-114.] Previously, historian Akeia de Barros Gomes located the family of Cesar Bonner (1755-1833), a baker, living in 1810 at 23 Thomas Street (now called the Isaac Rice House, after Bonner’s stepson).[15] In 1812, Abraham Casey, Sr. (1750-1817),a carpenter, lived at what was designated # 28 Levin Street.[16]

“Properties of William Handy, Divided into Lots and Streets Laid Out by John Gould, Surveyor (March 1801).” Newport Probate, Vol. 8:113-114, Newport City Hall. Men of African heritage owned Lots #24 through #28 between William and Levin Streets in the first decade of the nineteenth century

This historian pieced together a neighborhood that emerged post-Revolution with the addition of these families of African heritage: Mein, Brinley, Davis, Wanton, Easton, Hicks, Handy, Pease, and Dyre.

In 1811, Cesar Mein owned the southern quarter of Lot #24 before Cesar Bonner purchased it. Alexander Jack (1779-1843), cordwainer, purchased the northern quarter of Lot #24, 31 feet 6 inches [hereafter] on Mushroom Lane (later Levin Street), 62 feet east on Thomas Street, 31 feet 6 inches south on land of Cesar Mein, and 62 feet west on Edward Willis [LE 12: 262, 13: 568]. Alexander Jack is considered a descendant of a Black family from Antigua. However, in each census from 1790, he was listed as White, as were his two wives. Newport Restoration Foundation moved his ca 1811 home from 59 Levin Street to 49 Mill Street in 1969.

Pompey Brinley (1779-1813) bought part of Lot #26 from Samuel Greene in the Handy subdivision in September 1804. Pompey and his wife Esther lived at 73 Levin Street (31 feet 6 inches north and 31 feet 6 inches south on William Street), which was one half of the 63 feet x 123 feet surveyed lot [LE 42: 727 (1872) Youngken, p. 69]. It was not demolished until 1997.

John (Jack) Davis (1756-1836) bought one half of Lot #25 from shopkeeper Samuel Greene in 1804 in the Handy subdivision, 68 William Street, which stayed in the family for generations. The house still stands one room deep, two stories high, 738 square feet on a lot of about 3,000 square feet [LE 24: 317 (1842)].

Ceazar Wanton (died 1835) left his house and lot near Golden Hill Street to Fanny Davis (1770-1843), the wife of his friend Jack Davis, who lived on William Street [NP 10: 303-305, NP 13: 283, 430].

Cato Easton, laborer, and wife Cynthia (Almy) Easton bought house and land from Nathan B. Hammett, Housewright, and wife Mary (Billings) in 1808 [LE 49: 133 (1891)]. The lot #27 was bounded south 31 feet 6 inches on William Street and north 31 feet 6 inches on Levin Street with Pomp Brinley to the east and John Davis to the west. Their son was Alexander Easton.

Alexander Easton (1802-1872) and his wife Caroline bought out his sister, Jane, and her husband, John Howe, to own the Easton lot on Levin Street abutting Pomp Brinley [NP 5:92 and LE 24: 533 (1842)]. Alexander and Caroline Easton with John and Patience Philipps sold land north on William Street bounded by Nathan Hammett to the south and Alexander Jack to the east in 1837 [LE 21: 513].

Cudjo Hicks and his wife Freelove lived on William Street on a lot bought in 1800 from Nathan Hammett. Hicks was co-owner of the 2,774 square feet lot with Quam Handy [LE 15: 86. (1822)]. Their daughter Mehitable Hicks (1782-1833) married Hannibal Collins (1781-1833) and lived in the house.

Also on William Street, in 1815, her brother Samuel Hicks (1791-1861), a “free Man of Color, Mariner,” bought from Benjamin Hammett and his wife, Leah (Fairbanks). The lot was west of Cudjo Hicks. Samuel lived there with his wife Mary Ann (Stoddard) Hicks in a 795 square-foot house that still stands at 37 William Street [LE 13:120].

Kingston Pease, black ball maker (maker of shoe polish), bought a lot from Niobe Greene in 1783 and sold the lot in 1786. Kingston Pease formerly owned land south of the Hicks family, as noted on a deed of Alexander Jack in 1823. Pease leased this house to Cupid Brown in 1792 [LE 3: 378, 379, LE 4: 495, LE 27: 185, Town Council, Ap. 1823, 89. Vol. 1674B, 161, Newport Historical Society].

Rosanna Dyer and Silvia Easton lived and died in a house (ca. 1790) once owned by Benjamin Hammett. It still stands at #36 William Street, an 845 square foot home on a 2,348 square foot lot [Youngken, p. 78].

Easton’s Point

The Easton family owned twenty acres in the northwest of town adjacent to the harbor. In 1702, Nicholas Easton’s third wife Ann gave the large area to the Quakers, who had the land surveyed for over a hundred house lots in 1725. The Point was close to jobs like boat building, cabinet and furniture making, soap and tallow making, block and mast making and distilling along Bridge Street to Long Wharf.

“Divisions of Easton’s Point, Newport, RI,” a Map Copied by Henry Jackson from Newport Land Evidence Plat Book 2, p. 3, Newport City Hall. Free men and women owned lots # 105, 106, 108, 110, 112, 115, 116, 125, 127, and 129

Historian de Barros Gomes located eight families of African heritage living in Easton’s Point. Charles Chaloner, Sr., possibly a candlemaker, free in 1769 (died 1804), owned three lots in 1792 [Acct. Bk. Proprietors of Easton’s Point, 106]. Francis Chaloner (1778-1865), mariner, grandson son of Charles Chaloner Sr., owned Lot # 112 on Second Street from 1790 until it was foreclosed in 1823 [LE 16: 220, LE 31: 7]. Cuff Rodman (1769-1809), laborer, and his wife Sarah (Stevens) Rodman inherited Lots # 115 and #116 [NP 4: 648, NP 6: 48, LE 26: 397]. Kirby (Kibeah, also Cubber) Rodman (1736-1806) left his house for his wife Rachel; the property was on Third Street where descendant Nancy Rodman lived [NP 4: 383 (1808)]. Henry and Charlotte (Mowatt) Clark lived at the corner of Second and Willow Street with her parents, Quash Mowatt (1734-1823), mariner, and his wife Harriet sold their land to Henry Bliven before departing for Liberia [LE 15: 262].) John and Bess Beard owned two lots, #105 and #106; one of their houses stands today at 31 Willow Street. Arthur Flagg, Sr. owned Lot #112 at the corner of Third Street and Poplar Street, 42 Poplar, in 1807 [LE 10: 283]. Zingo Stevens, bricklayer and stonecutter, and his three wives lived in 1797 at the corner of Poplar and Third Streets [NP 5: 565, 571(1817), Acct. Bk. Proprietors of Easton’s Point, vol. 610, 146, 148, NHS].

Historian Youngken identified two men of African heritage whose properties were moved to the Point neighborhood. Nathaniel Rodman (1772-1848) owned Lot # 108 in the second division in Easton’s Point. The 1,408 square foot home stands at 13 Second Street at the corner with Bridge Street, having been moved from Kingston and Warner Streets in 1969. Rodman sold the house to Alexander Anderson of Providence, another man of color [LE 11: 183, LE 21: 107 (1835)]. Neptune Thurston, cooper, lived in a house two stories high and one room deep, which was moved from Long Wharf to 41 Walnut Street in 1883.

Research on homeowners in this neighborhood revealed additional information about the Thurston, Weeden, Phillips, and Lyndon families.

Cato Thurston, laborer (died 1822) and his wife Flora James paid for Lot #129 in Easton’s Point from 1785-1800 at £2.8 per quarter year [Acct. Bk. Proprietors of Easton’s Point, vol. 610 NHS].

Primus Thurston, distiller, and his wife Violet, sold lots, #125 and #127 in the Point in 1813, before declaring bankruptcy in 1814, according to the Rhode Island Republican. The deed indicated the lots were previously owned by William Tilley [LE 12: 644, LE 13: 8, Acct. Bk Proprietors Easton’s Point, 350]. He owned the lots in 1800.

In 1802, Thomas Weeden and wife Ruth bought a house on Washington Street. When the land went to auction in 1810, their son Philip, a mariner, purchased the home [NP 4: 568, 581 (1809), LE 10:163, LE 12: 60].

John Phillips and his wife Patience (Mowatt) (Sherman) Phillips lived at 72 Poplar Street.

Cesar Lyndon, Secretary of the Free African Union Society and the clerk for Governor Josias Lyndon, lived with his wife Sarah (Searing) at 107 Walnut Street in 1790.

Pope Street, South End of Newport

In the south end of town, the Redwood family-owned meadow lands. Black families settled along a rural roadway, called Negro Lane. By 1777, the name changed to Pope Street, after Abraham Redwood’s daughter married Captain Francis Pope. Historian Youngken located Jack Mason (John Nubia, or Salmar Nubia) (ca. 1756-1826) at 21 Pope Street when he sold his property to Nathan Hammett [LE 15: 166]. Newport Gardner (1746-1826), the famous music teacher and school principal, known as Nkrumah Mireku, was at 25 Pope Street [LE 15: 265]. Bacchus Overing, distiller (died 1810), and his son Paul Overing (1784-1857), restaurant owner and carpenter, lived at 29 Pope Street (ca. 1790) [NP 5: 497, LE 12: 65, LE 15: 407].

“The South End of Newport,” from a larger map, “A Plan for the Town of Newport, Rhode Island,” by Charles Blaskowitz and William Faden (London, 1777). Lower Pope Street, Bowery, and Young Street became the location for homes of the Armstrong, Barker, Collins, Fairweather, and Thurston families.

After continuing the research, it was evident another six Black families lived on or near Pope Street in the post-Revolutionary era (named Barker, Collins, Elliot, Armstrong, Fayerweather, and Thurston).

Cato Barker owned two lots near Pope Street as he was an abutter in the sale of property made by Stephen Deblois to Gordon Dickson, distiller, in 1808. One lot was 66 feet east to west by 45 feet north to south; Cato was the abutter to the south. The other lot was 40 feet north to south by 20 feet east to west. Cato Barker’s land was on the west and fronted on Pope Street [LE 10: 316].

Barry (also Burrey) Collins, laborer, left his house and lot to his wife Obour (Tanner) Collins (ca.1750-1835). It was located on the south side of Bowery Street, previously the ropewalk of Evan Malbone.[17] The bounds were noted in the sale of the lot to physician David King by Obour in October 1831. To the north of Collins was Bowery Street west on Sam Crapon, east and south on land of Samuel Whitehorne [NP 5: 305, 331 (1817), LE 18: 356].

Lincoln Elliot, laborer, bought #38 on the north side of Pope Street from John Howard, Yeoman, in December 1791 and did not record it until 1828. It is located east on land formerly of Jonas Redwood, west and north on John Howard, and south on Pope Street. His property went to Cesar Armstrong, farmer, and a son Peter Armstrong, mariner, who lived there until his death at sea in 1848. The property was sold at auction in 1853 by the town [NP 17:10, 81, 95 and LE 17: 80, LE 17:198].

George Fayerweather (sometimes spelled Fairweather or Fearweather) owned land at #18 Pope Street in 1809. When distiller Gordon Dickson bought a lot, Fayerweather owned the lot to the east [LE 11: 114]. When Abraham Redwood in London deeded land on the west side of Spring Street and Pope Street to Redwood Library in 1834, Fayerweather was the abutter to the west on Pope Street [LE 20: 187].[18]

Cato Thurston, laborer (died 1822), and his wife, Violet, bought land from Henry Clannen, sailmaker, and wife Mary, in 1808, referred to when the house and lot on north side of Young Street were sold to Isaac Gould in 1849 after Thurston’s wife died [NP 6: 345, 562, LE 27: 400].

Other Areas of Settlement

John Mowatt, grocer (1779-1859) and his wife Patience Mowatt (1787-1865) bought a property in 1818 at 83 Division Street where they ran their produce store for over a decade. They also had a liquor license from the town by July 1830. He left the house to his wife, Patience, who sold it to Reverend Michael Eddy in 1861 [NP 19: 394 (1827) and LE 39: 609].

Robert Keith (died 1799) and wife Roseanna lived on the east side of Thames near the Point from 1795 [NP 3: 186, 210 (1801) and LE 8: 700].

Isaac Babcock, gardener, and his wife, Phebe, in 1822 owned a house at 15 School Street [LE 16: 116].

Conclusion

From the time of the American Revolution through the decades of nation building after independence, freed African Americans lived in many different neighborhoods of Newport. Affordability, proximity to jobs, and opportunities for multiple uses for their property led many to purchase in areas like New Town, Easton’s Point, the Handy subdivision, and Pope Street. In the Federal Census of 1810, there were 264 free African Americans residing in 89 households headed by free African Americans.[19] at least 49 free individuals of color owned property out of the 89 heads of households in Newport’s Black population of 630. This amounts to half of all free heads of households. The expanding number of Black homeowners, landowners, and businessmen was the first step to permanent residence in Newport and status among the emerging leaders of the African American community. Political rights as taxpayers would be decades in the future.

The George Johnson House (1790), which stands at the corner of Spruce Street (now Kingston Avenue) and Johnson Court in Newport is 18’ by 28’ with 500 square feet on each of two levels (the Author)

Notes:

[1] Richard C. Youngken, African Americans in Newport: An Introduction to the Heritage of African Americans in Newport, Rhode Island 1700-1945 (Newport, 1998). Youngken identified Pope Street and New Town areas of settlement, as well as residents Newport Gardner, Arthur Flagg, Duchess Quamino (ca. 1739-1804), Cesar Lyndon, and Pomp Brinley. Most of his research was on the nineteenth century. [2] Akeia A.F. Benard, “The Free African American Cultural Landscape: Newport, RI, 1774-1826,” Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Connecticut, 2008. Accessed at https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/dissertations/AAI3308227/. Professionally, the historian is known as Dr. Akeia de Barros Gomes. In 2024, the Newport Historical Society appointed her as Director of the new Center for Black History in Newport. [3] James C. Garman, “From the School-Lands to Kerry Hill: Two centuries of Urban Development at the Northern End of Newport, RI” (2009). Accessed at https://digitalcommons.Salve.edu. Garman located in New Town Cuff Simmons, Bacchus Coggeshall, Cato Barker, Cesar Potter, the Johnson heirs, Ann, and Hannah Gardner. [4] William H. Robinson, ed., Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society, Newport, Rhode Island, 1780-1824 (Providence, RI: The Urban League of Rhode Island, 1976). The Newport Historical Society also has the complete manuscript copies of the organization in volumes 1674A, 1674B, and 1674C, as well as for successor organizations, the African Humane Society and the African Benevolent Society.Trinity Church ran the Bray School for enslaved and free Black children from 1762 to 1775. See John B. Hattendorf, Semper Eadem: A History of Trinity Church in Newport 1698-2000 (Newport: Trinity Church, 2001), 30-38, 120.

[5] Cherry Fletcher Bamberg, “Newport’s Town Records, Lost and Found,” Newport History,101: 290 (Winter 2024), 61-101.

[6] Eileen O’Brien, Newport City Clerk, showed me a map of the Handy subdivision from the later years of the nineteenth century. Many of the large lots were divided further and sold. Sometimes three houses sat on the original surveyed land. [7] Accessed at https://www.ricurrency.com/timeline-of-rhode-island-banking/. Bank loans were available for white families with the opening of the Bank of Rhode Island (Newport) in 1795. Four other banks opened their doors by 1819, but no record has been found of bank loans advanced to Black men in this period. In 1905, Armstead Hurley founded the Rhode Island Loan and Investment Company, the first Black owned bank in Rhode Island. [8] Cesar Lyndon, a clerk, documented several loans that the FAUS made to help prospective Black buyers. George Johnson, free Black mariner, held notes of $400 from men to whom he loaned money. Newport Probate [hereafter NP] 6: 86 (1820). All probate and deed records were found at Newport City Hall. Bacchus Coggeshall, NP 4: 509 (1808). He held a mortgage to the land of Cesar Potter. NP Vol. 5: 92-93, 100 (1812); he held a note worth over $456 with John Easton. [9] Garman, “From the School-Lands to Kerry Hill,” 4. The first term used for rental of the school lands was “fee farms” to collect money for Newport schools. [10] Newport Land Evidence [hereafter LE] 8: 92-93 (Mar. 25, 1801). The mortgage was to be paid by 1804, but Rev. Thurston died. Nevertheless, Cato Thurston paid in full by May 1788. Acct. Bk. for the Proprietors of Easton’s Point, vol. 610, 86, Newport Historical Society. See John Stevens III Account Book 1783-1794, p. 161. Cato Thurston paid for gravestones for family members. Thurston Genealogy #5528, p. 263. Tom Kennedy, “The Reverend Gardner Thurston,” The Green Light of the Point Association (Spring 2008), 10, 15, 17. Newport Mercury, April 1765. Reverend Gardner Thurston owned and lived in a second house, located between Cross Street on the west and Thames Street on the east and south on Amory Corner, a small gore of land on Thames Street East, closer to his church. Will of Abigail (Thurston) (Dyre) Bennett (1686-1761), Box 1. Land Evidence, Newport Historical Society. Gardner inherited the house from his widowed Aunt Abigail in 1757. [11] Proceedings of the Free African Union Society, vol. 1674B, 175. NP 4: 685-686, 707 (1810) and LE 34: 353-354. In 1858, a descendant, Eliza Flagg, sold the house and lot. [12] The Flagg lot is referenced in another deed of a neighbor, Declaration of Independence signer William Ellery, Esq. (1728-1820). After Ellery died, his youngest son George Wanton Ellery (1789-1867) in 1828 bought the property. The abutters were “North on land of Silas Dean, East on Thames Street, South on land of Arthur Flagg, a Blackman, and West on a back street” (Cross Street). LE 17: 35. See Blaine Papers Mss. 1079, Box 8, Folder 4, Rhode Island Historical Society. Joseph Blaine used Thomas Hornsby’s recollections, “Downtown Newport in 1770-1800-1949,” printed in Newport Daily Advertiser (Dec. 1849) and reprinted by George Champlin Mason in the Newport Mercury in 1872 to record the following: “Captain William Read at 89 Thames West and later William Ellery family to 1872. Arthur Flagg at 90 Thames West, “a very worthy and pious Black man lived with his family to 1849.” Benjamin Hall at 91Thames West with his descendants for 70 years; George Hall at 92 Thames West. John Stevens at 93 Thames West had a shop for working in marble; Rev. Gardner Thurston at 94 Thames West.” See LE 34: Oct. 19, 1857, where Eliza Flagg paid $1.00 to Mary Jane and Ann Benson for the property of their grandfather Arthur Flagg, Sr., East on Thames, North on George W. Ellery, West on Cross St., and South on land of William Messer. [13] Garman, “From the School-Lands to Kerry Hill,” 2. [14] NP 1: 145, NP 2: 353 (1793), NP 6: 24, 86 (1820), LE 15: 24. James Garman found that John and Sarah Chavers and John G. Moses occupied Lot #18 for a time as “owners” with no deed from either Brown or Johnson. See also Marian Mathison Desrosiers, “Sylvia Banister and Her Family,” Rhode Island Roots, vol. 49, No. 3 (Sept. 2023), 114-137. The Johnson descendants eventually lived on the inherited land. [15] LE 12: 23. See Cherry Fletcher Bamberg, “Isaac Rice and Sarah Ann (Conner) Rice and Their Children (Part One),” Rhode Island Roots, vol. 49, No. 4 (Dec. 2023), 194-219. [16] Will of Casey, Jr. NP 15: 83, 92, LE 13: 478 (1812), LE 25: 504 (1846). Antoinette Downing and Vincent Scully, The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island (C.N. Potter, 1967), 509. The Casey house was demolished to build Memorial Boulevard in 1969 to connect to America’s Cup Avenue. Youngken indicated that the Chaloners lived on a lot in the Handy subdivision on Levin Street. [17] Richard L. Champlin, “The Art, Trade, or Mystery of the Ropemaker,” Newport History, vol. 152 (Fall 1973), 1-19. At least ten ropewalks existed. Buliod’s ropewalk was from Farewell Street to Poplar Street; Flag and Collins was along Farewell and the Quaker cemetery. Tilley was co-owner of a ropewalk on what would become Callendar Street in New Town. [18] The Newport Fayerweathers are connected to the Fayerweather family of Kingston. The George II who owned the property in Newport was likely the same man who had built in 1820 and owned a house in Kingston that still stands. He was a blacksmith, and with his wife Nancy Rodman, a Narragansett, had a son, Solomon, who was also a blacksmith in Kingston. Another son, George III, married abolitionist Sarah Harris Fayerweather. The original enslaver of the Fayerweathers was the Reverend Samuel Fayerweather, who was the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in South Kingstown from 1760 to 1781. See Christian M. McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 147-51 and 248-52. [19] Akeia Benard, in her dissertation on p. 120, referenced W. D. Pierson, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro American Subculture in Eighteenth Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 47.

Author’s Note: Several probate records indicate property left to wives: Pero Nichols to Affebe [NP 3: 214 (1800)]; Prince Champlin to Lydia [NP 4: 44 (1803)]; Scipio Tanner to Peggy [NP 5: 511, 531 (1819)]; and Cato Willet to Diana [NP 6: 552 (1824)]. Once the names of their descendants are known, deeds may be located.