By the late summer of 1918, the World War had achieved the nadir of state authorized mayhem. Millions were dead, diseased, and wounded. Homeless, starving men, women, and children stalked Europe’s cities seeking food and shelter. Europe’s face was pocked with bomb craters, deep-lined by offal filled trenches, tread upon by tanks, and fumed with lethal gasses. It wore the tired look of disillusionment and ‘profound despair.

Here, in Westerly, moderately safe from the discomforts of the Great War “over there,” folks did the best with what they had. That winter of 1917-1918 was a troubled one when the December temperatures icicled down into minus teens below zero Fahrenheit — that was cold. The Westerly Sun ran a story about workers who claimed it was too cold to cut ice on the Pawcatuck River. (In those days ice was cut and stored underground for use the following summer.) Some did not complain. They could save time and distance by walking across the solid river to their workplaces in Pawcatuck. On the other hand, the frozen river prevented coal barges’ travel upstream to Westerly to unload their bituminous heaps on the Main Street docks. Fuel to heat Westerly had to be rationed.

Everyone in Westerly was concerned with food rationing as well. With so much American foodstuffs under export to aid the war effort, measures to ensure sufficient nourishment for the home front became necessary. Rhode Island newspapers published an Official Weekly Fair Price List. The Price List came with a caveat: “Below are given the fair prices on stable food commodities. If dealer charges more for an item than the price list below, please report and send your sales slip, if possible, to Robert W. Hamilton, Federal Food Administration of Rhode Island, State House.” About 30 food staples were listed with the price range allowed: butter (tub), per pound, .56-.58; eggs (fresh Western) per dozen, .60-.64; potatoes, No. 1 per pound, .036-.04; sugar (granulated, bulk), per pound .075-.08 were some examples of price listed commodities.

The Arctic-like weather was not all that captured local peoples’ attention. Throughout the war years incessant, intense Liberty Bond drives filled the local paper with figures of amounts raised to date. An insatiable need for material and the money to pay for it ground down the economy. People would be asked why Westerly could not raise more money than other towns of comparable size and wealth.

On a lighter economic note, Westerly’s barbers, members of Local 761, United Barbers of America, on May 1, 1918, agreed to a new price schedule: shave, 15 cents; haircut, 25 cents; shampoo, 25 cents; and a relaxing massage, 25 cents. Not all barbers were to enjoy this new prosperity. The tonsorial parlor of Andrew Ruffino, with its satellite pool tables, located in Burdick’s Hall (present-day Bradford Post Office) suffered fire damage on the night of Wednesday, July 11, 1918. Ruffino, who worked days at the Bradford Dyeing Association, experienced a malfunction when lighting oil stove, which he used to heat water, causing the conflagration.

Ellery Burdick, a grocer located on the same first floor of Burdick’s Hall, suffered water and fire damage. Though the flames did reach the Hall’s second floor, the large hall up there used for showing motion pictures and other social occasions, was not much harmed.

The American Red Cross came into its own during the war-to-end-all-wars. The Red Cross sought Westerly volunteers for a broad range of war-related activities including the wrapping of Pershing packets, or surgical dressings “for use on the front line trenches,” as exclaimed in the March 29, 1918 edition of the Westerly Sun. Men and women were needed to staff Red Cross canteens for American troops on the Western Front.

Most pressing on local nerves were repeated calls for more men to fight the war. At first, volunteers leaped into the fray. But, as word trickled back from Europe of local men who had been killed or wounded, that initial enthusiasm ebbed. Congress had foreseen this problem in 1916 when it passed the National Defense Act, increasing the military’s authorized strength. In 1917 the Selective Service Act, or the draft, became law. So the recruiting and drafting continued in Westerly. Men whose names were selected for the draft were frequently published in the Sun’s front pages. That was a comfort because these servicemen were keeping the enemy at bay, far from the homeland.

The state of the nation’s public health, however, was a growing problem not extensively covered in the local newspapers. Measles and the Spanish flu were illnesses that hadn’t really affected the Westerly region. But, the war, soldiers’ living conditions, and a general absence of public health information meant that inexorably these diseases would creep their way into the Westerly community.

In the same 1917-1918 time segment some national newspapers reported the deaths of servicemen from measles. In 1917 that epidemic resulted from the cramped living conditions recruits had to endure. Military training bases began to receive at least twice the number of men that space had been allotted for. Trainees were compressed onto substandard barracks or field tents during that bitterly cold winter, often without heat or hot water. Sanitary facilities offered to the men were of a primitive quality. Measles spread nationwide with the transfer of newly trained troops to various new posts.[1]

One historian explained, “the first recorded case of Spanish Influenza occurred at Fort Riley, Kansas. On March 11, 1918, a company cook reported !to the base hospital with flu-like symptoms.” Within a week, “522 similar cases had been recorded in the files of the Fort Riley Hospital.”[2] Soon thereafter outbreaks of the influenza were reported at six other Army installations. The U.S. Navy was also informing the public of flu cases at its ships ported on the East Coast.

At New England’s army training installation, Camp Devens, 23 miles north of Worcester, Massachusetts, housing and sanitation conditions were deplorable. “In a single day, 1,543 Camp Devens [Mass.] reported in with influenza. On September 22, [1918], 19.6 per cent of the entire camp was on sick report, and almost 75 percent of those on sick report had been hospitalized. By then, pneumonias, and the deaths, had begun.”[3]

The seriousness of the military’s health problems struck home in early September 1918. The Commandant of the Second Naval District, Boston, Rear Admiral Joseph W Oman “directed that for the time being none of the enlisted personnel of the district on leave shall leave Newport without a special pass.”[4] The admiral’s order followed newspaper reports of local recruits dying in basic training of pneumonia brought on by encounters with the Spanish flu virus. The quarantine order, however, did nothing to save the life of a Westerly boy, John Irving Shippee, 21, “who died of influenza at the Newport Naval Station,” the Westerly Sun reported in its September 23 edition.

The problems the influenza epidemic posed to the military community understandably were seen as a distant black cloud to the local populace. But that nonchalance changed when the enemy disease began to affect the civilian population. The Westerly Sun reported on its September 25 front page the death of William E Murray, Boston’s postmaster, who “succumbed to pneumonia induced by influenza.” The newspaper also announced the passing of Ashaway resident, Harold R.W. Peterson, a pneumonia casualty following a bout with the flu.

By the close of September, lacking a statewide prescribed action plan, Westerly health officials decided to act on their own to head off the epidemic exploding its way into town. At that time Spanish influenza was not a disease that the Rhode Island Board of Health required local municipalities to report incidences of, or deaths from. But Westerly’s Public Health Officer, Dr. Samuel C. Webster (99 High Street) was not one to allow the towns peoples’ health to be undermined.

He told the Sun, “If I had my way I would abolish all gatherings, close all churches, close the theaters and stop people from traveling on trolley cars, and in fact, gathering together in any place that is not well ventilated.” Even though Rhode Island’s governor Robert Livingston Beeckman (1915-1921), Dr. Byron U. Richards, secretary of the State Board of Health; and, Dr. Charles V. Chapin, Providence’s Superintendent of Health, and others at a meeting in the capital city decided “to hold in abeyance, for the time being at least the closing of” public gathering places “due to favorable weather conditions,” area officials began to implement measures to stymie the epidemic’s further proliferation.

During a consultation with Dr. Willard H. Bacon, Westerly Public School Superintendent, Dr. Webster learned that 400 students or about 25 % of the district’s student population were home ill with the flu. He advised the school chief to close the schools, which he did “for an unspecified period of time.”

Other public gathering places were called upon to temporarily close their doors. Frank Vennette, manager of the Bliven Opera House on 96 Main Street, canceled orders for Boston-booked films. The Central and Princess Theaters followed suit. Rev. Clayton A. Burton, pastor of the Seventh-day Baptist Church and Rev. John G. Dutton of the Christian Church announced their church doors would be closed for services.

Three of the Shore Line Electric Company’s men—dispatcher Frank Bailey of Palmer Street; conductor Thomas McGowan of North Stonington, and, William Howard of Mechanic Street— were flogged by the flu as well, as were 20 other trolley workers. Yet, the line continued to operate on its normal schedule albeit with more cars in service to prevent passenger contagion.

Dr. Webster ordered the children’s reading room at the Westerly Public Library “closed until further notice.” And, on the weight of his advice to the Westerly Town Council, that body voted to close soda fountains immediately. Soda fountain operators took umbrage with this ruling because saloons were allowed to remain in business, Westerly Police Chief Thomas E. Brown was ordered, by the Council, to strictly enforce the new ruling.

In Connecticut where the epidemic’s effects were not as pronounced, Charles H. Gavitt, a West Broad Street undertaker, was instructed by Hartford officials “to hold no public funeral…where the person has died of Spanish influenza.” Stonington’s Health Officer, Dr. Charles F. Congdon, required all saloonkeepers “to forbid men gathering at their saloons after patronizing the bar:’ A negligent bar keep would find his watering hole boarded up by the police.

Several days later, Dr. Charles F. Congdon, Stonington’s Health Officer, ordered the closing of all public, private, and parochial schools in Pawcatuck and the Borough as well as all theaters and movie houses in the affected areas “until further notice.”

In nearby Ashaway, several cases of serious illness resulting from the flu were reported. When “the attendance at the Ashaway High School [present-day Ashaway Elementary School] was diminished to about a quarter of the usual number of students,” the school board, on the advice of School Superintendent S. Hussey Reed, quickly closed that building “for the coming week, or until ordered to reopen by the school board.”[5] Perhaps, what brought the seriousness of the situation to Sup. Reed’s attention was the absence of Professor Albert B. Crandall, principal of the Hopkinton grammar and high school, who had been stricken by the flu. It is not too unreasonable to speculate that a number of the faculty didn’t report to their classrooms for the same reason.

October 1918 was an extremely important month in the lives of Westerly’s citizens. It was an opportunity to be on their very best behavior, to be outgoing and caring for others in distress. The Spanish Influenza epidemic had hit hardest in the town’s North End. Those suffering the most were families of Italian immigrants. Folks who had come to America to build a new life for themselves and families; they provided a lot of the labor which powered Westerly industries. These new arrivals were people whose lives centered on close family ties and closer living conditions. With so many people living in a small clannish community it was inevitable that an epidemic which thrives on air-borne contagion would spread rapidly. And so it was that more than “700 cases” of the flu were estimated by one of Westerly’s physicians, Dr. John L. May (19 Canal St.), who had been attending many of them.

This was an age of self-reliance. No one sought or expected “the government” to do anything — at least not at first. Citizens felt a sense of responsibility for each other’s health and safety. When there were scores of families in the town “where every member [was] ill and it [was] impossible to get any outsider to assist in the caring for those afflicted with the disease,” two volunteer health organizations leaped into the breach. They offered emergency medical care and food to families struggling to survive.

The Westerly Chapter of the American Red Cross called upon the women of the town to help care for the sick. Before volunteers entered afflicted homes, Red Cross workers fitted the women with special gauze masks made by Chapter workers to prevent contagion. Red Cross headquarters was then located at 18 Elm Street.

The Westerly Sanitary Corps (today’s Westerly Ambulance Corps) under the leadership of its commander, Dr. Frank I. Payne, threw its heart and soul into the work ahead. Notified by the Red Cross of the conditions threatening the town, members established a headquarters in the Boy Scout Hall on High Street. They had a telephone installed, beds placed for men to rest upon between their six hour patrols, and utensil sterilization equipment on hand to protect themselves from contagion. “Four young ladies volunteered” to answer phone calls and provide secretarial support under the direction of Miss Elizabeth Hoag.[6] Patrols from the Westerly Sanitary Corps went directly into the homes where they rendered first aid to the sick. Serious cases were reported to WSC headquarters who assigned doctors to follow up with the necessary treatment. Patrols also delivered food, donated by the townspeople, to those in need.

The Westerly Sanitary Corps’ crowning effort during this crisis was the establishment of an emergency hospital at the Beach Street School. (At this time Westerly had no public hospital. Its sole private hospital was the Westerly Sanatorium, a large gambrel style red brick building facing Wilcox Park at 3 1/2 Granite Street. Dr. John Champlin, out of a sense of responsibility to the public, built the hospital and opened it in February 1910.[7]) Some months before Corps members had completed some renovations to this unused elementary school building at 113 Beach Street in anticipation of just such a need. The emergency hospital was wrought out of the school’s two commodious classrooms and principal’s office. “Within five hours, the school, now -a hospital, was open and the heat on.” Patients in the worst stages of the disease were treated there on its 29 beds, When the patients began to recover, they were sent to another empty school in the North End of town to complete their recovery. The Rhode Island Garage Company (Dixon House Square) donated an ambulance to transport patients for the duration.

Word of the WSC’s excellent work reached officials at the State Board of Health in Providence. Here is what it wrote of that volunteer body’s performance:

In some of our towns and cities the work was truly remarkable, and no community in this country could have excelled that which was performed in Westerly, and we doubt if any will be able to equal the promptness and efficiency shown in the emergency work there, under the guidance of the Westerly Sanitary Corps as indicated by the following: The request for the opening of the hospital was received at 8 o’clock in the evening. Three minutes later some of the members of the corps were on their way to the schoolhouse. Before midnight repairs were completed and the cots made ready in the two large wards, and shortly after daylight following there were 29 patients under treatment.

This work included electrical wiring thorough overhauling and quite extensive repairing of the plumbing system, the knocking down and reconstruction of the heating plant and some important carpenter work. This was done at the Beach Street School, a building abandoned sometime ago, yet in a very satisfactory state for use as a hospital.[7]]

The second tier emergency hospital was the empty Pleasant Street School and its annex (yes, portable classrooms in the back of the building. Does anything really change in the school business?) Patients housed in this building were on their way to a full recovery. Also treated and cared for at this facility were children from families “who have either been left orphans or whose parents are unable to take care of them.” Dr. Bacon placed the children, now almost numbering 40, in the care of public school teachers who worked there on a rotating shift basis. Appeals were published requesting cribs and cots for the Pleasant Street facility. Dr. Champlin cared for five of the children at his hospital.

Westerly’s cadre of doctors fanned out among the sick offering their expert skills. Dr. John L. May, however, had to cease his efforts due to exhaustion caused by an extremely heavy workload and long sleepless hours. Although former Westerly Health Officer, Dr. Michael Henry Scanlon, was struck down by the disease, following his recovery, he continued to administer medicines and see patients at his office. Others doctors who waged the battle against the disease were Dr. Howard D. Kenyon (88 High Street), Dr, C. Grant Savage (7 Elm Street), and Dr. Asa Sheldon Briggs (Ashaway). Dr. Briggs also worked in Bradford as that area’s physician, Dr. David F. Marr, (Main Street, Bradford) had been called to serve in the U.S. Army in late September.[8]

Continuing the trend begun in September, the death toll from pneumonia brought on by the flu further escalated in October. In Westerly the fatalities were scattered about in many homes. Some victims’ names can be mentioned here: James Murano, 3, of Tower Street, son of Mr. & Mrs. Louis Murano; Beatrice Williams, a Westerly High School senior, daughter of Mr. & Mrs. Bertram D. Williams of Mystic; Angela Cafone [sic.], 6 months, 86 Oak Street; John D. Holland, Jr., 22, son of John Holland of Main Street; Edward Tailon, 31, an acting sergeant in the 4th Company R.I.N.G. of Greenman Avenue, left a wife and three children; and, Charles L. Clarke, 38, of School Street, left a wife and two daughters; Charles and Rose (Brocano) Ferraro of Haswell Street. “The Ferraro case on Haswell Street is one of sadness…The husband Charles died Monday [Sept. 30] and Mrs. Ferraro passed away yesterday [Oct. 1], leaving four small children. They have no relatives here, but they are being well cared for:” Olivia M. Datson, daughter of Army Captain & Mrs. Abraham P. Datson of Park Avenue, and Dr. James M. Crowley, 32, a Westerly dentist, mourned by his wife, Sarah (Leahy) Crowley of 71 High Street.

The local newspaper reported on the grave apprehension felt in the town. “During the past 48 hours there have been 12 deaths from Spanish influenza and pneumonia, bringing the total number of victims up to 47” over the past two weeks. People were becoming nervous about their own safety. Dr. Webster said it would require a guard at every home to have individual quarantines imposed. There were stories of ill people wandering the streets, some with sick children in their arms, seeking a doctor’s care. It was estimated that 80% of the cases popping up town-wide were to be found in the North End. The Sun declared, “The disease is worst in the Italian section of the town.” It was clear that some desperate measure was required to slow the epidemic’s spread.

A request was made of the Commander, Captain Abraham P. Datson, of the 4th Company, R.I.N.G., at the Dixon Street Armory to station guards in the Pierce Street area. Was it the Westerly Town Council’s wish, or did Dr. Webster do the asking? The answer is still not clear. Other sections of the town had suffered the flu’s illness and death, but the Guard wasn’t sent to those homes. Why the “Italian section”?

Guards were posted along a rectangular perimeter extending from the corner of Pierce and High Streets down Pierce Street to Canal Street. And, from the corner of Pleasant and High Streets soldiers walked down Pleasant Street to Canal Street. The canal and the distance between the corners of Pleasant and Pierce Street along High Street formed the two short sides of the geometric figure.

The guard was there to keep people moving and to stop them from visiting homes which held influenza patients. Most area residents took “kindly” to the regime, appearing to appreciate this imposed form of protection. A few residents raised objections. However, as Dr. Webster had said, “You can’t contract the disease unless you come in actual personal contact with someone who has it.”

On the same day the R.I. National Guard took up perimeter positions in the North End neighborhood this list of deceased victims was published: Pasquale Gentile, 20 Pierce Street; Mrs. Harry Soloveitzic, 5 Canal Street; John DeBartolo, 75 Pierce Street; Mrs. Mary Lavarto, 19, wife of Joseph Lavarto, 9 Pond Street; Mrs. Philomena Spino, 24, wife of Michael Spino, 76 1/2 Pierce Street; Frank Murano, corner of High and Dixon Streets, survived by his wife and three children; and, John Leonetti, laborer, Marion Street.

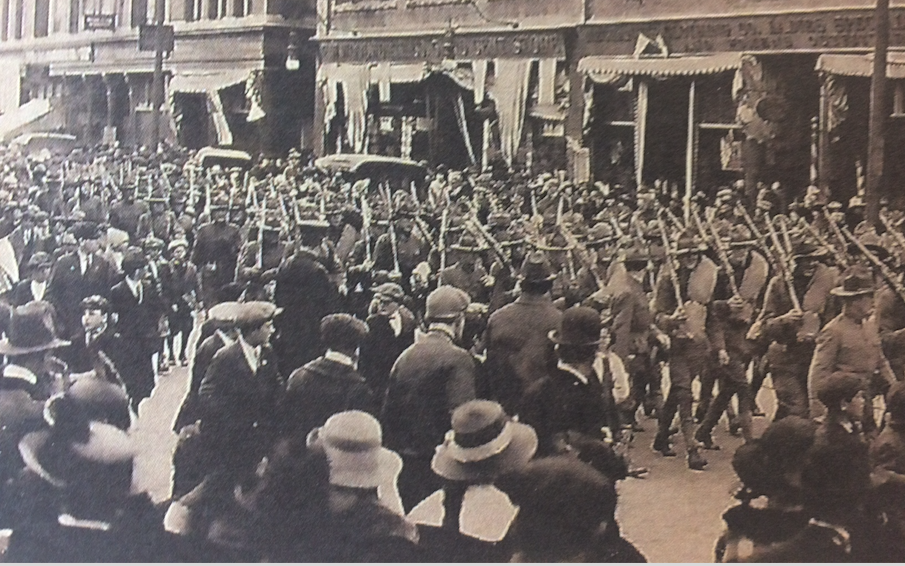

The tugboat Westerly, laden with soldiers from World War I, easily identifiable by their round hats and putties worn above their boots (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

When the death rate stopped climbing towards the middle of October, saloons and soda fountains were allowed to reopen. Westerly schools which were to resume classes on Monday, October 14, will now do so on Wednesday the 23rd, according to an announcement made by Dr. Willard Bacon.

As if by Divine Intercession, Westerly received a much needed morale boost or a kind of comic relief toward the end of October. As the epidemic was winding down, William Ashley “Billy” Sunday (1863-1935), the anti-booze evangelist who couldn’t shut Chicago’s bars down, blew into Westerly on a whirlwind crusade of this part of the nation. It seems incomprehensible that so very soon after the health problems experienced here that he would try to pack 1500, men only, into the Bliven Opera House to hear him speak. He was to give his one-hour anti-liquor speech on Friday, October 25. Employers even let men off work at the factories and shops in time to hear him speak. Quarries did not close down, but made arrangements “so that anyone desiring to hear Billy may leave their work at 11:30.”

Billy Sunday could have been the Elvis Presley of his time for the excited reaction he got from the Westerly High School students when he showed up unannounced at the Broad Street address. At 11:30, the students heard the bell ring and ring. Was this a fire drill, or what? Sunday gave them his 15-minute stump speech in the auditorium. Then he skipped down Union Street to the Opera House on Main Street. He could probably hear the applause all the way.

But wait, weren’t crowds the cause of contagion? Maybe he was the tonic people needed to cheer them up.

In November the enemy epidemic “went away.” The previous month’s turbulence slowed to such a degree that the local Red Cross people were publicly seeking funds to clear up a $600 flu-related debt. Chapter Treasurer, James M. Pendleton, expressed a hope that citizens would be grateful for the benefits so recently received.

There was a flare-up of influenza in Bradford toward Christmas, but it was not accompanied by the disease’s former virulence. People now knew to see a doctor straightaway when they felt the widely publicized symptoms. The patient initially felt a chill followed by a high temperature (100-104 degrees Fahrenheit). The fever would last from three to five days, followed by nausea, uneasiness, and depression. The Infected mucous membranes in the noses, throat, and bronchial tubes would produce a prolonged cough. Doctors, if notified in time, were able to treat these symptoms and affect a cure and complete recovery.

No official records of the number of dead or who were affected by this disease in Westerly were kept. Many more names of those who suffered and who perished could be added here.

The State Board of Health in late December 1918 decided to make mandatory the reporting of the Spanish influenza. The Board was prompted into action by a suggestion made by Rupert Blue, the U.S. Surgeon General, head of the U.S. Public Health Service.[9]

Some statistics are available today, however. In response to a request the author made to the Rhode Island Department of Health, produced these figures:[10]

Year Influenza Deaths in Rhode Island

1917 128

1918 2,306

1919 596

In the end, the enemy disease was defeated and expelled from the town by the hard work and caution of its intrepid citizens.

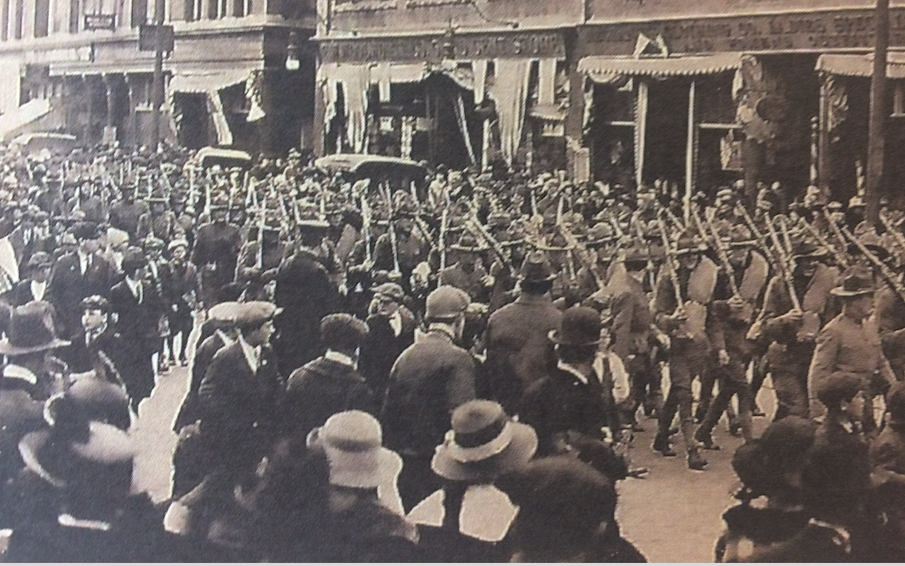

[Banner image: Troops marching down Westerly’s High Street, probably in 1917 (Author’s Collection)]

Notes:

[1] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Viking, 2004), 148-149. [2] Virginia Aronson, The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2000), 42-45. [3] Barry, The Great Influenza, 187. [4] Providence Journal, September 14, 1918. [5] Westerly Sun, September 30, 1918. [6] Westerly Sun, October 9, 1918. [7] Byron U. Richards, M.D., Secretary, Fortieth Annual Report of the State Board of Health of the State of Rhode Island for the Year Ending December 31,1919, 31-32. [good] [7] Westerly Sun, February 4, 1910). [8] Westerly Sun, September 23, 1918. [9] Providence Journal, December 27, 1918). [10] Will Smith of the Rhode Island Department of Health to Thomas O’Connell, May 31, 2006.