In early October 1927, baseball sluggers Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig arrived at Providence to play an exhibition baseball game. It was a memorable day for kids and adults alike.

At the time, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were two of the most famous men in America. Their team, the New York Yankees, had just won 114 games and swept the World Series in four games over the Pittsburgh Pirates. Their Yankees’ team is considered one of the best baseball teams of all time.

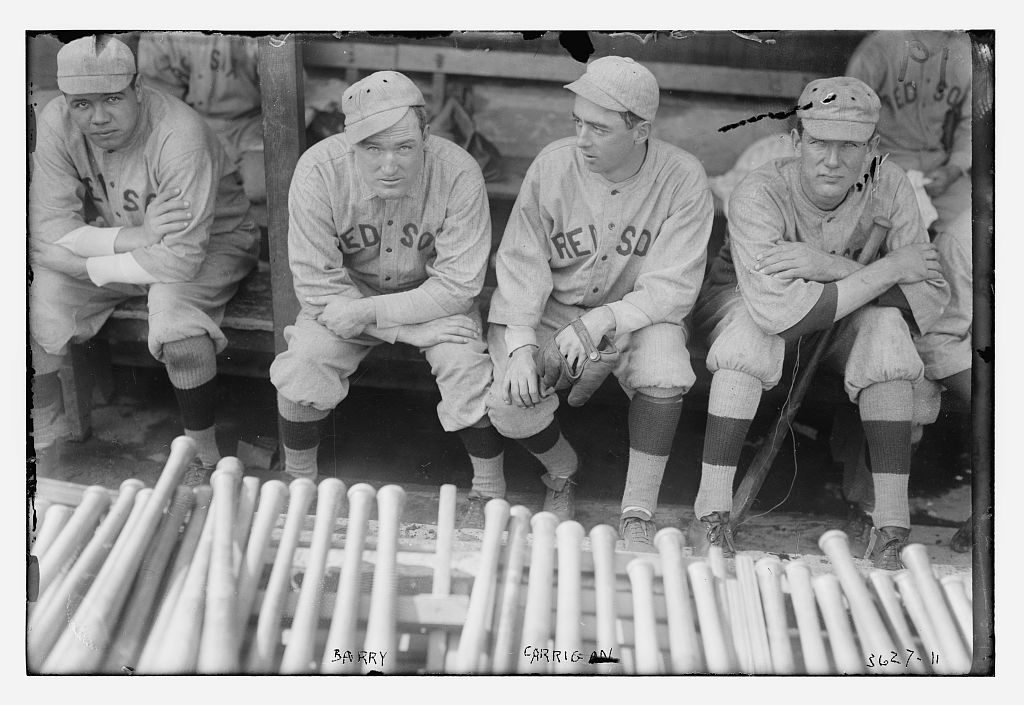

Babe Ruth started his major league career with the Boston Red Sox, helping them win pennants with his pitching in 1915, 1916 and 1918. He is on the far left here in 1915, his first full season as a major leaguer. In the prior year, he played in Providence (Library of Congress)

Ruth and Gehrig had monster years batting in 1927. Ruth hit .356, with 60 homers (more than any other team in the American League) and drove in 164 RBIs. He walked 137 times and scored 158 runs. His slugging percentage of .772 is still one of the best of all time. At 32, he had one of his best seasons.

Lou Gehrig was right with Ruth in batting, hitting for an average of .373, with 47 homers and 175 RBIs. Hitting behind Ruth in the lineup, he slugged .765, also one of the best of all time. His 117 extra-base hits are second only to Ruth’s 119 in 1921. He bagged 447 total bases (no one has had more since), including 52 doubles and 18 triples. “Larrapin Lou” was only 24 years-old, and just 436 games into his amazing streak of 2,130 consecutive games played. Gehrig won baseball’s most valuable player award in 1927. Ruth might have won it instead, but at the time, a player was allowed to win the award only once — Ruth had won in 1923.

But just two days after winning the Word Series at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx on Saturday, October 8, baseball’s two biggest stars hit the road for a national barnstorming tour, arriving at Providence on Monday, October 10. Christy Walsh, Ruth’s business manager, organized a 21-game tour aimed at showcasing the two sluggers. Games were played from Providence to San Diego, with many of the towns in between small in size. After completing the tour, Walsh reported that Ruth and Gehrig had traveled more than 8,000 miles for games in nine states and that about 220,000 fans had attended the games.

Why would Ruth and Gehrig put themselves through the grueling task of traveling across country by slow train and in cars on poor roads? They could earn more money, doubling their salaries. Ruth and Gehrig were not paid by the Yankees what they were worth. As a result of major league baseball’s “reserve clause,” a baseball team in effect owned its players. The player could not be a free agent and negotiate with other teams. For Ruth and Gehrig, it was either playing for the Yankees or sitting at home. As a result of what probably is the worst U.S. Supreme Court decision of all time (at least based on the law), baseball’s noncompetition arrangements could not be challenged under federal antitrust laws. Because the team owners had such negotiating power, player salaries were kept artificially low. Barnstorming across the country was a way for Ruth and Gehrig to make more money—and for fans to see them in action.

Their 1927 tour netted nearly $220,000. Ruth earned a $70,000 salary from the Yankees in 1927 (almost as much as the U.S. President’s salary, a shocked public learned), and matched it on the cross-country tour. The younger Gehrig, too, reportedly doubled his $8,000 salary, though he was about to get a new Yankees contract paying him $25,000 a year.

Christy Walsh had not expected the Yankees to sweep the Pirates in four games. With an unexpected gap in the schedule, Ruth and Gehrig agreed to begin their 1927 barnstorming tour at Providence.

Providence was special for the Babe. He had played with Providence Grays, then an outstanding minor league team, in 1914, his second time playing as a professional after leaving St. Mary’s orphanage in Baltimore. After joining the Grays on August 18, Ruth spent two months in Providence in 1914, part of only 46 games he spent in the minors. A mid-season Boston Red Sox pickup from the minor league Baltimore franchise, the Boston management thought Ruth needed experience in the minors. At the time Ruth was primarily a pitcher, but he could also wield the bat. Ruth hit his only minor league home run in a Grays uniform, a blast to right field in Toronto in a September 5 game in which he also tossed a one-hitter. Ruth led Providence to finish in first place in its league that season. In 1915, 1916, and 1918, Ruth’s pitching helped the Boston Red Sox to World Series championships, until he was traded to the Yankees in 1919 where he became legendary for his batting.

While residing in Providence, Ruth had befriended Tim O’Neill, known in Rhode Island as the “King of the Sandlots.” Since around the turn of the century, O’Neil had organized baseball leagues for young boys in Providence. At the time, he had six leagues with eight teams each.

Tim O’Neil, Providence’s “King of Sandlots,” is shown here with Babe Ruth before the start of the Providence exhibition game (Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame website)

Ruth wired Judge James E. Dooley in Providence on Sunday evening, October 9, informing him that he and Gehrig were booked on a train from New York City for Providence the next day. “Believe me, I am glad to come back to Providence where the fans treated me great when I was a green kid with the Grays.” Ruth then generously extolled the virtues of Gehrig, who had never visited Providence. Gehrig, though, would arrive shortly after Ruth. He stayed behind in New York City a few hours longer to comfort his mother, who had just been released from the hospital.

Monday’s morning Providence Journal newspaper contained an advertisement for the exhibition game that thrilled its readers: “Babe Ruth, King of Swat, and Lou Gehrig, Fence Buster, Will Positively Appear” that afternoon for an exhibition game at Kinsley Park.

Arriving at Providence’s Union Station at noon, Ruth was escorted to City Hall, where he was greeted on the steps by Providence’s Mayor James E. Dunne, Judge Dooley, and Ruth’s onetime teammate Jean Dubuc, then the coach of Brown University’s baseball squad. Ruth had a soft spot for Dubuc. While pitching for the Detroit Tigers, Dubuc had surrendered Ruth’s fifth major-league home run, the longest ever hit at Detroit’s Navin Field. In Providence, Ruth stayed at the Biltmore Hotel, where he was interviewed by local reporters. After being joined by Gehrig, the two men dressed for the afternoon game.

The exhibition game was played at Kinsley Park, where the Grays played. It was located at the corner of Kinsley Avenue and Acorn Street, across the street from the Nicholson File Company’s factory complex. The stadium was built by Peter Laudati, a prominent Providence developer who was also a part-owner of the Providence Steam Roller, a new professional football team that also played its home games at Kinsley Park. The next year the Steam Roller would win its league, becoming New England’s first team to win a major league football championship.

The Journal’s advertisement, and news spread by word of mouth, did the trick. By game time, there were thousands at Kinsley Park, including, according to one newspaper, “2,222” excited children.

Christy Walsh supplied the team uniforms the two stars would use in Providence and for the rest of the 1927 tour. Gehrig and his team wore white uniforms with “Larrapin’ Lous” emblazoned on them, while the Ruth and his team wore brown uniforms with the team name “Bustin’ Babes” on them.

Before the game, at 2:30 p.m., Ruth and Gehrig were feted to a tribute at home plate. A vaudeville star had planned to open his new burlesque show, “Cock-a-Doodle-Doo,” in Providence that day, but once he learned that Ruth and Gehrig would be staging their exhibition game, he cancelled the opening show and had all sixty of his chorus girls, dancers, jugglers, comedians, acrobats, band members, and other entertainers at home plate welcoming the two baseball stars. Joining them were Judge Dooley, Tim O’Neil, and Peter Laudati. Ruth and Gehrig posed for pictures with O’Neil.

Babe Ruth always took time with children, who adored him. Here he is with some young girls at Yankee Stadium in 1921 (Library of Congress)

The Journal noticed a few changes in the Babe, but also some familiar personality traits. Ruth was popular with the press, but was also known as a womanizer even in his Providence days. While he was “more portly, more famous” he was “no less genial,” the Journal reported. “As a matter of fact, between the boys and the chorus girls gathered about him at the plate, the Babe seemed to give preference to the boys,” the newspaper added.

Prior to the game, Ruth and Gehrig engaged in a home-running hitting contest, always a crowd pleaser on their tour. At the plate just before the game started, Tim O’Neill reviewed some new rules with the two umpires: Ruth and Gehrig could not be walked by any pitcher. The sluggers would either make a hit, hit into an out, or swing mightily at strike three. The paying attendees needed to see their money’s worth.

The following is a wonderful account of the exhibition game from Jane Leavy’s new book, The Big Fella, Babe Ruth and the World He Created:

Gehrig batted cleanup and played first base for the pennant-winning team from the Universal Winding Company, known as the Universals. Ruth batted cleanup and played the outfield for the runner-up team from the Immaculate Conception Institute, known as the ICI.

. . . .

The game resembled baseball for five innings. . . . When Ruth asked the opposing catcher Emilio “Cappy” Cappalli what to expect from the kid on the mound, Cappy said: “The straightball, no curves.” The kid struck him out on three straight curves. Decorum broke down. All that stood between Ruth and 2,222 boys was a score of overdressed Providence city cops and a flimsy railing marking the boundary between propriety and jubilation. They poured out of the grandstand and leaped from the box seats. They flew to him, climbed on him, clung to him.

Soon the kids began to storm the field between at-bats, and between pitches, accosting Ruth and Gehrig at their positions, and in the batter’s box, racing each other—and outracing the cops—for every batted ball. . . .

Ruth and Gehrig accommodated everyone, signing schoolbooks, pocketbooks, diaries, handkerchiefs, order slips, collars, and cuffs, “everything but blank checks, which earned them a 10,000 batting average in the signing department,” the [Evening Bulletin] paper said.

In the seventh inning, Ruth decided to take a turn on the mound, an ill-advised decision that yielded the only home run of the day, a majestic thing that sailed off Gehrig’s bat and over the center field fence.

In the eighth, Ruth meandered to the plate, two batters out of turn, to face Gehrig, who hadn’t pitched since his days on Morningside Heights. “Here began the greatest battle between a pitcher and a batter in the history of baseball,” the Providence Journal declared. “Gehrig struck him out three times and walked him at least once oftener than that.”

Ruth refused to leave the batter’s box. Gehrig kept pitching. Ruth kept swinging. The last of seven pecks of balls disappeared. Still the Babe refused to budge. Time was called. Tim O’Neill was compelled to surrender the last available ball in the ballpark—one signed by Ruth and Gehrig that he had sequestered in his jacket pocket.

“Babe waved the outfielders back and then on the 25th or 26th pitch . . . history being forever in the dark as to the exact number . . . The Babe hit the ball into right for a single and two men went over.”

A hundred kids fell on O’Neill’s souvenir. The umpires called Ruth out for batting out of turn and called the game on account of no more baseballs. The final score was either 13-7 or 13-9, depending on whether you counted the last two men to cross the plate.

Ruth’s main contact in Providence, Tim O’Neil, also invited the slugger for a testimonial dinner in O’Neil’s honor at the Biltmore Hotel in Providence on October 18. But by then Ruth and Gehrig and their barnstorming tour were in Sioux City, Iowa. Ruth telegraphed his regrets and sent a letter praising O’Neil’s volunteer work to be read in his absence. Attendees at the dinner honoring O’Neil included Herb Pennock, a star pitcher for the Yankees; Emil Fuchs, president of the Boston Braves baseball team; Reverend William A. Hickey, Bishop of Providence; Lieutenant Governor Norman S. Case; Mayor Dunne; and a judge and a priest who had played in O’Neil’s little league as children. O’Neil would continue organizing little leagues in the state for a total of sixty years. His work helped to spawn baseball little leagues and American Legion leagues throughout the country. He was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2013.

[Banner Image: Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig on their 1927 barnstorming tour]

Bibliography:

Jane Leavy, The Big Fella, Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York, NY: Harper, 2018) [Leavy’s recently-published book on Babe Ruth, which was the main source for this article, is recommended. She starts with Ruth’s exhibition tour as a way to get to know the Big Bambino. She also uncovers the details of Ruth’s early and difficult family life, which had been shrouded in mystery ever since he became a celebrity in the 1920s.]

Patrick T. Conley, “Timothy ‘Tim’ O’Neil,” at the online website for the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame (click on Sports – Baseball) @ www.riheritagehalloffame.com/inductees_detail.cfm?crit=det&iid=707

Providence Journal and Providence Evening Bulletin, Oct. 10-11, 1927.

Tom Emery, “For Many Decades, Providence was a Player in Baseball’s Minors,” Providence Journal, Aug. 9, 2015.

Wikipedia report on Kinsley Park.

“King of Sandlots Honored at Banquet,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Oct. 19, 1927 (Associated Press report).