Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, authors of an excellent history of King Phillips’ War (also called Metacom’s War), accurately describe the war as “America’s Forgotten Conflict.” It was the 17th century struggle between the tribes of southern and central New England and the English colonists and is rarely discussed today. This unfortunately means that those who participated in the war are mostly forgotten as well.

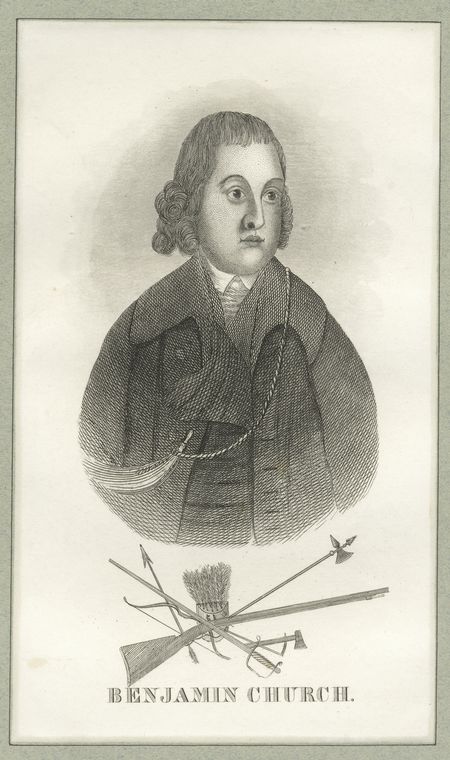

One of those forgotten men is a Rhode Islander who played a pivotal role in saving the English New Englanders from losing the war to the Indian leader, Metacom, or as the English knew him, King Philip, and his allied warriors. The Rhode Islander did so by learning and implementing the superior war tactics of the Indians during the summer of 1676. Along with his contribution to the English victory he also set in motion a new style of war that would be used for hundreds of years in North America. These tactics helped America claim its independence from Great Britain and an evolved version of these tactics are still used to this day by one of America’s most elite military units, the United States Army Rangers. This largely forgotten man is Benjamin Church and he was the “The First American Ranger.”

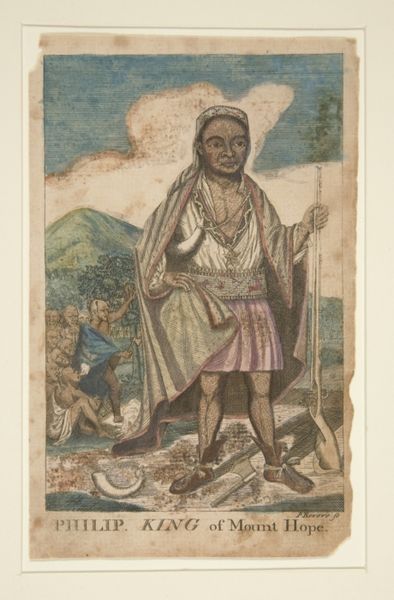

An image of King Philip, known among New England Indians as Metacom or Metacomet. It was not taken from real life.

Church was born in Plymouth Colony (now part of Massachusetts) in 1639 and learned to hunt and trap at a very early age. After marrying in 1667, Church eventually became one of the first settlers of “Sogkonate” (anglicized to Sakonnet) land that is now part of Little Compton, Rhode Island. Soon after his arrival in Rhode Island in 1674, he encountered the Sakonnet tribe (allied with or a subsect of the Wampanoags), who were led by the female Sachem, Awashonks. Church “gained a good acquaintance with the natives; got much into their favour, and was in a little time in great esteem among them.”[1] His civil relationship with the Sakonnet tribe is emblematic of the peaceful attitude Rhode Island colonists had with their Indian neighbors for most of the 17th century. However, the peaceful relationship between the Rhode Island colonists and their neighboring tribes would eventually be ruined by the larger, more intrusive surrounding white governments.

The governments were the Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Plymouth Bay colonies. To them the Indians were mere savages who were occupying land they wanted to seize to expand their towns and farms. From 1640 to 1670 the New England colonies saw their population grow to about 50,000, for a 300% growth rate. To support this growth, they began purchasing the Indian’s land, often in an unethical manner, while also intruding on the Indian way of life.

Although this encroachment severely irritated the tribes of New England, they had already been severely weakened by disease brought by Europeans even before the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth in 1620. The Massachusett tribe saw its population drop by 90% during the plague of 1616. As disease continued to migrate westward along with more English colonists, the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes eventually saw their populations fall as well. The Wampanoags were devasted, having its population fall from as many as 5,500 to 2,500. The Narragansetts avoided catastrophe, but still saw its population be reduced about 5,000 by the time of the outbreak of King Philip’s War.[2] Although weakened, the Wampanoag tribe of what are now Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts became fed up with its new neighbors and were ready to retaliate.

Igniting this retaliation was a 1675 murder trial. Three Wampanoags were charged with murdering a Massachusetts Indian named John Sassamon, who had converted to Christianity and had warned Plymouth’s governor about King Philip. After the Plymouth government had rashly charged the Wampanoag men with murdering Sassamon, they were quickly found guilty, sentenced to death, and executed. At this point the, after a Wampanoag was murdered in the custody of white men, Wampanoags decided that they had suffered enough from injustices. In June of 1675 King Philip’s men raided several homes in Swansea, Massachusetts, killing nine colonists. Over the next several months hostilities quickly escalated into a war that resulted in the highest death of Americans per capita in our nation’s history.[3]

During the period of the outbreak of fighting, Church failed to persuade his friend, Awashonks, and her tribe, from joining King Philip. The two former friends became temporary enemies. The war expanded in scope and violence in December 1675 when the strongest tribe in southeastern New England, the Narragansetts of Rhode Island, were forced into the conflict after English troops from Massachusetts, Plymouth and Connecticut conducted a surprise raid and savagely murdered hundreds of Narragansett men, women, and children in the Great Swamp Massacre.

For the first several months of the war, the colonists’ military tactics proved to be completely incapable of defending their settlements from the Indian raids. By the Spring of 1676, at least twenty towns across New England had been attacked or destroyed.[4] The English governments would have to act fast as the war was on the road to becoming a classic David over Goliath victory.

How was this possible? How were Indian tribes that were still recovering from years of disease able to wreak such havoc on the rapidly growing New England colonies? For Benjamin Church, the answer was simple: this was the New World, with a new style of war in forests that was not conducive to the colonists’ European war tactics. If the colonists wanted to win, they would have to learn how to fight like their enemy.

The fighting styles of the opposing parties could not have been more different. The Europeans were familiar with open battlefields and fighting with large, rigid armies fighting in tight formations. Although powerful, they were slow and the grouping of their soldiers created easy targets for the Indians. Reflecting back on the early part of the war years later, Church stated how the “English always kept in heap together, that it was as easy to hit them as to hit a house.”[5]

On the other hand, the Indians’ smaller military teams navigated the terrain with ease and moved swiftly around the rigid European soldiers. Instead of fighting out in the open, they shot from behind trees and rocks. One European soldier described a haunting image when he said “every stump shot like a musketeer.”[6]

Another skill the natives leaned on was their marksmanship. Shultz and Tougias describe how compared to the Native Americans “the English were slower in abandoning their inferior matchlocks and less likely to use their weapons in the daily procurement of food” and that “natives were often more adept with European technology than the English themselves.”[7] To put it simply, when it came to the skills and tactics needed to win this war, the advantage clearly was with the Indians. Eventually, after several months of defeat, logic prevailed and the Massachusetts and Plymouth Bay colonies began to incorporate the Indians’ style of warfare.

Benjamin Church was the ideal man for this job. Schultz and Tougias explain why this view was true, stating that his “willingness to form personal relationships with Indians gave Church an advantage among his fellow military officers in incorporating native tactics, in navigating the forests and swamps of New England, and in enlisting natives to the English cause.”[8] These traits enabled him to adopt his enemy’s tactics and helped to change the course of the war.

Early in the war, from the summer of 1675, Church served as the principal military aide to Governor Josiah Winslow of Plymouth Colony. It was not until July 1676 that he finally received approval to raise a mixed army of 200 volunteer soldiers, “the English not exceeding 60.”[9] As the requirement indicates, Church was to enlist non-English soldiers. To accomplish the impressive feat, he leaned on the friendships he developed his Indian neighbors in Little Compton. About a year after his first attempt to persuade Awashonks to join the side of the English, Church finally convinced her to fight with him side-by-side. Some Wampanoags also joined Church. This was yet another testament of the relationships he was able to forge with the Indian tribes of New England.

Now that he had his army, Church quickly began targeting key Native American leaders. Because of the participation of Awashonks and her people, and some Wampanoags who assisted Church, Church was able to gain valuable intelligence of enemy Indian leaders.

His first victim was Totoson, “sachem of the Mattapoisett and one of King Philip’s principal lieutenants during the war.”[10] Only months earlier, Totoson led a raid on English houses in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which resulted in the deaths of eleven colonists. Totoson also led the raid on Old Dartmouth in the summer of 1675, which enabled King Philip to narrowly escape capture at Mount Hope.

Upon discovering Totoson and his tribe’s location, Church’s army swiftly navigated the New England woods and took the Indian party by surprise. Church, being the hands on soldier he was, came face to face with Totoson “and struck the Muzzle of his Gun an inch and half into the back part of his head.” Thinking that his violent blow had killed Totoson, Church turned his back on Totoson, but before he knew it Totoson was “flying at him like a dragon.” Fortunately for Church, his men saw the Indian Sachem coming towards Church and fired at him, forcing him to flee.

By the end of the skirmish, Church proved his unit’s ability to navigate the New England forest and ambush enemy Indian warriors, using military tactics the Indians had used against the English so many times before. After the battle, he was able to boast that the number of Indians “they had killed and taken was 173.”[11] His next victory would prove to be the most notable of them all.

In early August, Church heard of the death of Totoson, possibly from heartbreak from losing his family members. Days later Church received word of Philip’s location from John Alderman. Alderman was a Wampanoag who had deserted Philip’s army after Philip killed his brother for suggesting the Wampanoag’s make peace with the English. Church was now aware that King Philip was camped out in Mount Hope and he decided to take advantage of the opportunity.

Church quickly mobilized his men and crossed into Mount Hope where the historic Mount Hope Bridge now stands. Church and another English officer, Captain Roger Goulding, planned a surprise attack against Philip and his supporters. The plan was to have Goulding charge and scare the enemy forces out of their camp and lead Philip directly to Church and his men. But the attack did not go exactly as planned—Captain Goulding thought an Indian saw him while hiding, so he began firing his musket. Church thought it was perhaps a single misfire but “before he could speak, a whole volley followed.”[12]

A view of the approximate location on Mount Hope Bay where Benjamin Church crossed to attack King Philip in 1676. The Mount Hope Bridge stands there today.

The battle was on and King Philip quickly grabbed a few essential items and began to flee. He ran right into two of Church’s men, an Englishman and John Alderman, the Indian. The Englishman fired first but missed so he quickly instructed Alderman to fire next. Alderman took aim, fired, reloaded, and fired again. In that time the course of the war took a dramatic turn. King Philip was now dead as Alderman “sent one musket bullet through his heart, and another not above two inches from it.”[13]

Church’s men, upon hearing of Philip’s death, yelled three loud “huzzahs!” as their new agile war tactics enabled them to accomplish what so many other English soldiers had failed to do for the past year. In fact, at the very start of the war, in July 1675, the colonial military under Captain James Cudworth of Massachusetts, had a similar opportunity to kill Philip when soldiers in his command learned of his whereabouts in present day Bristol, Rhode Island. They attempted to trap Philip but as usual, they acted too slowly and Philip was able to escape.[14] Church, who was critical of Cudworth and his delay to act, demonstrated the superiority of his army’s new war tactics.[15] However, the war was not over yet as many of Philip’s men escaped, including Anawan, a man whom Church described as a “a great soldier…and Philip’s chieftain all this war.”[16]

Although elderly at the time of King Philip’s War, Anawan was a fierce warrior. Instead of fleeing when the raid began in Mount Hope, he “hallooed with a loud voice, and often called out ‘Iootash, Iootash’ which meant to stand to it and fight stoutly.”[17] Church discovered the location of Anawan after a recently captured elderly Wampanoag led him to Philip’s camp. The old but fierce warrior was camped out in present day Rehoboth, Massachusetts, in a location surrounded by the Squannakonk Swamp. Captain Church arrived at Anawan’s location in late August and found Anawan and his men camped out on the side of some cliffs, along with Anawan’s son and a few of his chiefs. Church first ordered the elderly Indian that led Church’s men to the site to walk down to Anawan with his daughter to act as a sort of decoy. Church followed closely behind with his hatchet in hand and scaled the steep cliff. When Anawan eventually discovered Church and his men, it was too late. Anawan, his son, the chiefs, and the other Indian warriors were captured by Church and his soldiers.

That night, Benjamin Church ate a meal with Anawan and listened to his war stories, while those around them slept. This is a testament to Church’s willingness to learn from his enemy. At one point during the conversation Anawan walked away to grab something. Church, initially scared, put his hand on his gun, but quickly realized that he was being presented with some of the emblems of King Philip’s status as ruler. Upon placing these wampum belts and other royal items on Church, Anawan stated, “Great Captain, you have killed Philip, and conquered his Country for I believe, that I & my company are the last that War against the English, so suppose the War is ended by your means.”[18] Once again, Church illustrated his ability to lean on the New England natives’ knowledge of the land, coordinate a surprise attack with an agile unit, and capture another key Indian war leader along with his warriors.

Church rounded out his accomplishments by capturing King Philip’s brother-in-law and war chief, Tispaquin, Sachem of the Nemasket, in September 1676. Tispaquin was later beheaded and his family was sold into slavery in the Caribbean, as were, tragically, hundreds of other Indian captives.

By this time the balance of power had completely shifted to the English colonists. The Native Americans would never regain the initiative.

Along with Church’s military success there were other factors that contributed to the demise of the New England tribes. One of the most important factors was the killing of Narraganset war chief, Canonchet, in April 1676. Canonchet was considered one of the greatest Indian military strategists of the time. This skill was critical to the Indian uprising as King Philip’s ability to encourage the Indians to strike out was not matched by his military expertise or bravery on the battlefield. Therefore, when Canonchet was caught in Narragansett territory by Mohegan allies of the English and executed by them, it struck a devastating blow to the Indian uprising.

The Native Americans had also been so focused on destroying the surrounding towns that they did not sufficiently focus on growing and storing food. After the colonists had destroyed the food supplies of the Narragansetts at the Great Swam and at other places, the remaining Indians were largely fighting while undernourished for most of 1676—their women, children and elderly were underfed as well.

Another key factor that cannot be understated is the role neutral and disenchanted Native Americans played in providing key intelligence about Indian military tactics and the location of their leaders, while also fighting valiantly alongside the English. The ability of white armies to divide Indian nations that had been former enemies would be repeated in future wars in North America in the coming centuries.

While all of these factors were critical, it was Benjamin Church’s willingness to aggressively attack and kill or capture key Indian leaders that made an irreversible change to the balance of power between the two parties. After his victories it was only a matter of time until the English completely subdued the uprising. The Native Americans’ military efforts would stagger on for a few more years until 1678 when the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay.

After King Philip’s War, Benjamin Church continued his military career in the English army in North America in King William’s War and Queen Anne’s War. When he finally had enough of fighting, he wrote a book titled Entertaining passages relating to Philip’s War, which tells his first-hand account of the war. Church spent the remainder of his life in Little Compton until his death in 1678/9. He died at the age of 78 on January 17, 1717.

In the closing remarks of his book, The Skulking Way of War, which wonderfully describes the new style of war that Church adopted, the author Patrick J. Malone states how the Indians’ “skulking way of war” had “shaken the confidence of the colonists and had forced them to adopt a new doctrine for forest warfare.”[20] Any colonists who were initially skeptical of these new military tactics must have been quickly persuaded otherwise as they witnessed Benjamin Church use these new tactics to help subdue enemy Indians.

New England, as well as upstate New York, would see the ranger style of warfare perfected by Robert Rogers of New Hampshire and his rangers in the French and Indian War from 1755 to 1763. This style of warfare was also occasionally used by American forces in winning the war of independence against Great Britain in the American Revolution, particularly at the key American victories at Saratoga in New York and at King’s Mountain in South Carolina. This tradition has been carried today to one of the U.S. Army’s most elite military units, the Army Rangers. Benjamin Church, the first American Ranger, was the catalyst for this new mode of warfare being adopted by white military forces. This legacy is rarely spoken of today, but it helps to keep our country free.

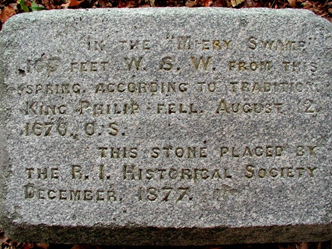

Monument in Mount Hope dedicated to where “King Philip fell on August 12 1676,” placed there by the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1877.

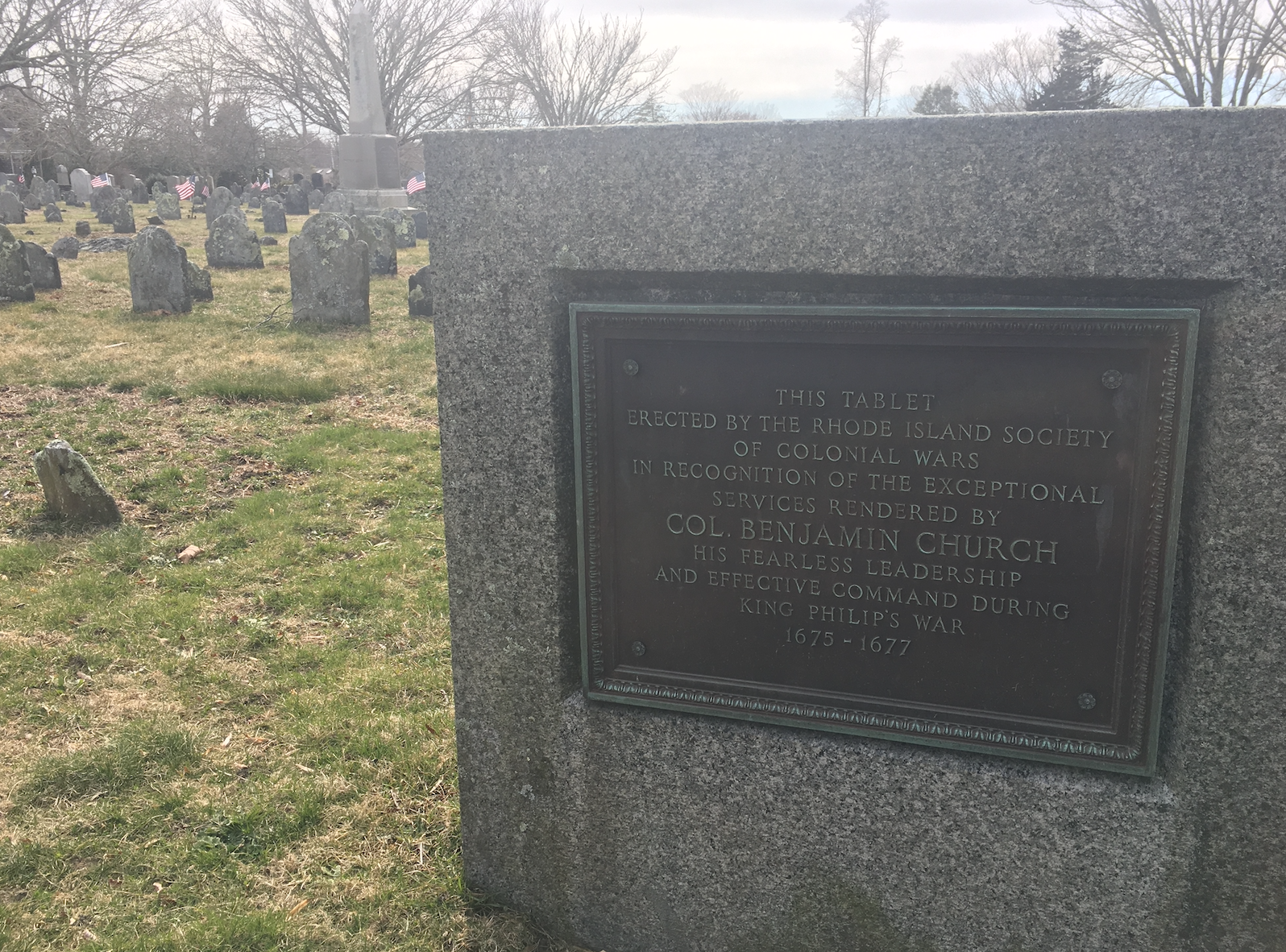

Benjamin Church’s burial place in the Old Burial Ground in Little Compton. The Ranger emblem can be seen at the top of his grave.

Benjamin Church’s burial place in the Old Burial Ground in Little Compton. The Ranger emblem can be seen at the top of his grave.

Sources:

[1] Thomas Church, The entertaining history of King Philip’s War, which began in the month of June, 1675 : As also of expeditions more lately made against the common enemy, and Indian rebels, in the eastern parts of New-England: with some account of the Divine Providence towards Col. Benjamin Church (Rhode Island: Independently Published, 1716), 19. [2] New England Historical Society, “Exactly How New England’s Indian Population Was Decimated,” accessed September 1, 2021, https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/exactly-new-englands-indian-population-decimated/ [3] James A. Warren, Gods, War, and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians against the Puritans of New England (New York, NY: Scribner, 2018), 246. [4] Joshua J. Mark, “Timeline & Battles of King Philip’s War,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed October 10, 2021. [5] Church, The entertaining history of King Philip’s War, 61. [6] Patrick M. Malone, The Skulking Way of War, Technology and Tactics Among the New England Indians (Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 2000), 88. [7] Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War, The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press), 16. [8] Ibid., 40. [9] Patrick M. Malone, The Skulking Way of War, 92. [10] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 115. [11] Church, The entertaining history of King Philip’s War, 67. [12] Ibid., 71. [13] Ibid., 72. [14] Schultz and Tougias, King Philip’s War, 45. [15] Ibid., 289-290. [16] Church, The entertaining history of King Philip’s War, 79. [17] Ibid., 72. [18] Ibid., 53. [19] Patrick M. Malone, The Skulking Way of War, 96. [20] Ibid., 100.