I was just 18 years old, a college freshman, on May 4, 1970, when National Guardsmen in Ohio opened fire and killed four student protestors at Kent State University. Fifty years later, I still remember the looks on peoples’ faces as news of the shootings spread like lightning across my own college campus a thousand miles away at Brown University in Providence.

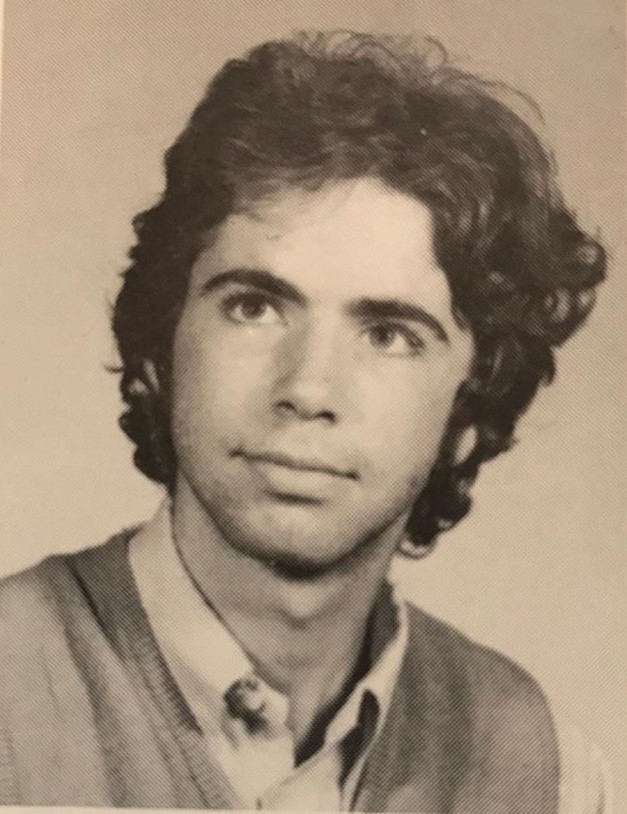

Brown University students, on the College Green in front of University Hall, protest the shootings at Kent State, the week of May 4, 1970. Brown was not known as a radical campus, but the Kent State killings spurred large protests (Kenneth D. Ackerman)

Those were dramatic times. President Richard Nixon had just announced his invasion of Cambodia that week. I remember watching Nixon give that speech in a crowded dorm room on a small, grainy black-and-white TV as people shouted, hooted, threw things at the screen. With news of the Kent State shootings, our campus within hours was on strike.

Brown University in 1970 was a relatively small school that had just undergone a major change in response to student protests the year before: the adoption of a New Curriculum featuring optional grades, no course requirements, and more student control. My class was the first of this experiment, adding to the sense of tumult. And now the school had shut down. Classes were suspended.

On Strike!!

The campus quickly erupted in protests, pickets, meetings, fevered gossip. Questions raged over whether the school would cancel final exams, how grades would be assigned, what to do about graduation. Rock and roll music blared from dorm windows, making the scene electric. Ours was one of over 400 colleges on strike that week – the largest student protest ever. If campus protests ever had the chance to make any difference in the real world, now seemed the time. How exciting to be caught up in this extraordinary moment!

Driving all these events was the Vietnam War, by 1970 in its fifth year with more than 500,000 American troops deployed and no end in sight. Hundreds of American soldiers were dying every week along with thousands of Vietnamese. And we college kids felt ourselves directly in the target zone. The Selective Service, the draft, hung over our lives like a noose, ready to pull us out of school or snap us up the minute we left, then ship us off to kill or die. Over 2.2 million kids around my age, all men, were drafted during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1973. Tens of thousands never came home alive.

The next summer I would see my own name come up in the draft lottery. Number 14 (out of 365). A bullseye. The war was no abstraction. It was tangible, immediate. And nobody was neutral about it. For my viewpoint, there seemed nothing honorable or patriotic about this conflict halfway around the world. We seemed to be fighting on the wrong side, killing people we didn’t know and had no quarrel with, wreaking pointless oceans of pain and loss, our own government using bully tactics here at home, lies, police clubs, and undercover spies, to stifle dissent. Obviously, plenty of people disagreed.

The killings at Kent State of white, middle class protest kids just like us got more publicity, but these weren’t alone. They came on top of similar killings at Jackson State College in Mississippi and Berkeley’s Peoples Park, let alone the police riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago just two summers before in 1968. Construction workers had beaten up protestors that week at the World Trade Center site in New York City. Richard Nixon had publicly called us all “bums.” Passions ran red hot, fear, anger, a loyalty to generation, my circle. It was “us” and “them.”

The war had already colored my first year of college. The protest movement was everywhere. Already I had participated in two large protest marches that fall. In October I had traveled to New York for the first Moratorium Against the War, a raucous march of 100,000 people from Columbia University down to Bryant Park some 60 blocks away. (On that trip, I also had the chance of a lifetime to attend the deciding game five of the 1969 World Series with my nephew Jim, also unforgettable.) Then, a month later, I had travelled south to Washington, DC – my first trip ever to what would become my home of 40+ years – for the November 1969 Moratorium, which drew half a million people marching up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Washington Monument to hear the folk music group Peter Paul and Mary and a raft of speakers.

That day in Washington I even got to march with the charismatic writer Norman Mailer. My friend Lou Peck and I spotted Mailer along the route and joined his group of friends for a block or so. Before nightfall, I’d had my first whiff of tear gas from the National Guard. I loved being involved in the movement, the marches, the protests. It felt like the most important thing I had ever done with my life – far more exciting and relevant than mere college classes or anything else. And yes, I admit, it was fun! Action!

So when the chance came in May 1970, just days after the Kent State shootings, to join a handful of classmates and a professor and drive overnight down to Washington, D.C., this time to participate in a hastily-called protest over the Kent State shootings and the Cambodia invasion, I jumped at it.

On to Washington!!

I’ve forgotten many details about that trip more than fifty years ago. How I wish I’d taken notes! Professor Strauss, who drove us down to DC, taught Applied Mathematics at Brown, and I had taken a basic class he taught on computers. There was no such thing as a computer or IT department at the time. These machines remained exotic, rare animals back then, cumbersome, primitive, mysterious. What passed in 1970 for a basic course in computers involved punch cards, endless loops of coding, and reams of print-out pages. No screens, no mice, no cool-looking gear. They were fascinating, but hardly seemed practical or useful in any way. Times would obviously change on that score.

I remember how, reaching DC, we stayed overnight with friends of the professor who had a house in the Maryland suburbs. We were just a handful, the professor plus three or four students. I remember arriving at the march itself the next morning in the professor’s car, a station wagon. Where did he park the car? As an adult, I would have obsessed the entire day over that question. As a protest kid, I never even noticed. Even now, when I think of that day, I still wonder about it.

The rally took place on the Ellipse, the park in Washington just south of the White House and across from the Washington Monument. Newspapers estimated the crowd at 100,000, congregating since the night before. President Nixon had actually slipped out of the White House and visited some of the protestors camping out around the Lincoln Monument in a creepy, awkward pre-dawn exchange. The White House grounds themselves had been circled with buses parked bumper-to-bumper, sealing off the area as Secret Service and other troops mobilized inside. Armed police and National Guard were visible everywhere on the street.

And then there was the weather. That day, May 9, was hot, a special condition local Washingtonians know all-too-well as Hazy, Hot, and Humid. For outsiders like me from colder climates up north, the thick heat could knock you down or take your breath away.

Arriving at the rally, we were met by some of the march organizers. When Professor Strauss told them we came from Brown University – considered a relatively moderate campus — they decided to give us armbands and assign us as marshals. Our job was to help cordon off a small area near the front stage that served as a first aid station with doctors and medical tents — a busy place that day with kids passing out from the heat or experiencing side effects from the many underground drugs of that era.

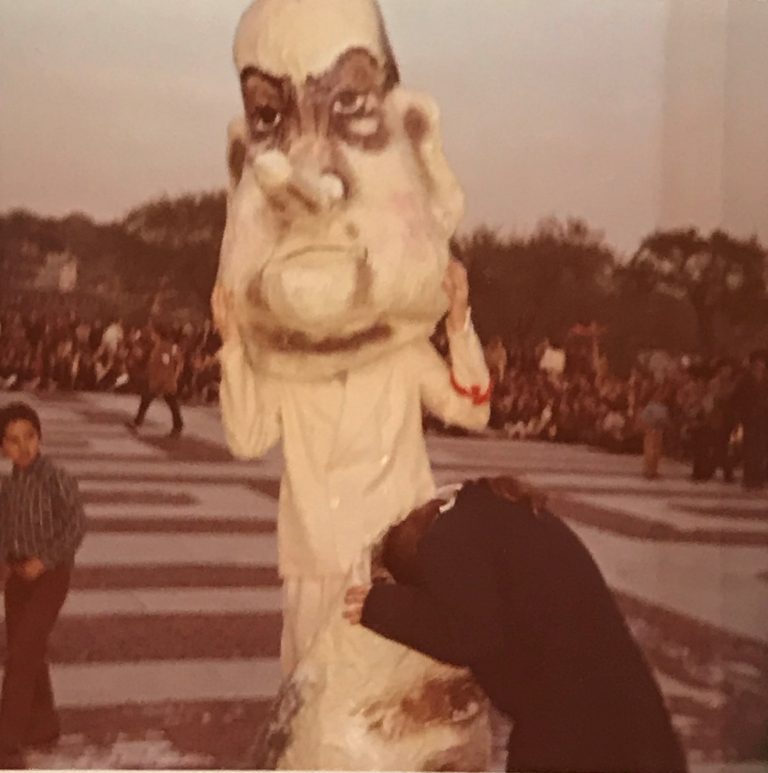

I don’t remember much of the big rally itself. There were speeches, cheering, noise, people, music. TV cameras and news crews dotted the scene. But the real action came after the main event broke up. By then, late afternoon, after hours in the heat, marinated with drugs, beer, and lots of sitting around, most of the people seemed wiped out. The Washington Post noted how the heat made this crowd more passive, less agitated than at other recent demonstrations. But not all. Others just got impatient.

A homemade “papier mâché” puppet of President Richard Nixon at anti-war protest march in Washington, DC, on May 9, 1970 (Kenneth D. Ackerman collection)

Up at the front where we were, a few march leaders decided we hadn’t finished yet. They had brought half-a-dozen wooden boxes to use as props, shaped like coffins and each one draped with a sign for one of the recent shootings: Kent State, Jackson State, Peoples Park, so on. Wouldn’t it be a great idea, they announced, to carry them around to the front of the White House and deliver them to the doorstep of that murderer inside, Richard Nixon himself. Cheers rose up and off we went. Our entire part of the crowd got up and started marching toward the White House.

Off to Storm the White House!!

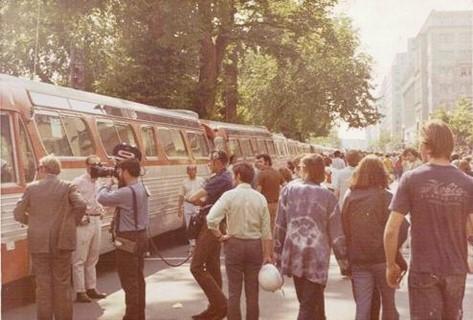

I have checked this part of the story against newspaper accounts, just to make sure my own memory hadn’t gotten it wrong. And in fact, according to the Washington Post and other sources, a group of about 10,000 splintered off at that point on a mission to deliver those prop caskets to the president’s door. We marched from the Ellipse up 15th Street past the Treasury Building, then around the perimeter of bumper-to-bumper busses toward Pennsylvania Avenue.

I remember that march vividly, how we flooded the street. People climbed up lamp posts to take photos. Police, heavily armed military, were visible in all directions, on rooftops, at corners. The crowd had a carnival mood, loud, active, alive. We all shouted chants together, like marching music to clapping hands and drums and whistles. I remember two in particular I’d never heard before: “Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh! The N. L. F. is Gonna Win!!” and “Two! Four! Six! Eight! Organize and Smash the State!!”

A crowd of protestors marching up 15th Street in Washington, D.C., near the White House, on the day of the protest, May 9, 1970 (Kenneth D. Ackerman)

What did these even mean? The N.L.F. – National Liberation Front – was the formal name for the Viet Cong, the group we were fighting at that moment in Vietnam. Was this treason against the country? In that moment, I didn’t seem to matter. The words were clever and striking and bold. I wouldn’t learn until much later that these two chants happened to be favorites of a radical group called the Weather Underground involved with bombings and arson. These were now my friends and comrades on that day, on that street, in that moment of good fun and shared adventure.

I also noticed, looking at the other marchers, how many of them, men and women alike, wore hard-hat helmets, the kind construction workers use. At the time, I thought it was probably just a style statement – solidarity with the working class? — like the red bandannas and small canteens. Silly, naive me, not realizing that the hard hats were protection from police clubs and the bandannas, with a splash of water, from tear gas. These were not novices, my new friends. They came prepared.

On we marched, filling the street, chanting the chants, following the mock coffins, until we found ourselves on Pennsylvania Avenue directly in front of the White House. A few years later, in 1995 after the Oklahoma City bombing, the Secret Service would block off this section of Pennsylvania Avenue from local traffic, a security measure hardened and expanded after the attacks of September 11, 2001. But back in 1970, Pennsylvania Avenue was just another street, and that’s where we stood now.

Having reached this point, the crowd grew restive. What next? The White House was blocked by the bumper-to-bumper buses. There was no way in. But the leaders up front had an answer: Let’s deliver the coffins by simply lifting them and heaving them over the buses. Cheers and whistles rose from the crowd as dozens of hands and arms joined in lifting the wooden boxes and as high as they could, but they couldn’t quite reach the tops of the buses.

What now? Again, no hesitation. The leaders up front, barely 10 feet away from where I stood with my little cadre of co-students and professor in the middle of the crowd, announced the answer. Let’s knock over the buses!! They can’t stop us!! Power to the People!! Right On!!

Tip the Buses!!

And so the buses started shaking. Hundreds of hands and arms from the crowd now concentrated all their strength on rocking those buses, harder and harder, tilting them further and further. Realistically, could they actually have knocked one over? Or at least pushed it far enough to make an opening? And what if they did? What next? Were we ready to charge through? And what was waiting behind those buses? Soldiers? Police? National Guard?

A few years later, I would get a direct answer to that question. By the mid-1970s I was working as staff counsel to a US Senator and, one day at a Capitol Hill reception, I happened to meet one of the Marines assigned to the White House grounds that day. We started sharing stories. What he told me was this: “It’s a good thing you guys never managed to knock over that bus.” Stationed behind those buses, he explained, were not only Secret Service and DC police but also US Marines with live ammunition, instructed to protect the perimeter of the White House. Things could have gotten ugly very fast.

But we didn’t know that at the time. Maybe some suspected it, but nobody seemed to care, nobody seemed nervous. Instead, we were caught up in the moment, the cheers, the chants, the energy, the thousands of voices, the leaders urging us on.

Buses parked bumper-to-bumper to seal off the White House grounds from demonstrators, May 9, 1970 (Kenneth D. Ackerman)

It was at this precise moment that Professor Strauss managed to get our attention and pull our small group together into a tiny huddle like football players. I remember his words almost exactly. He said: “I know a really good Chinese restaurant over that way,” pointing in the direction away from the White House. “If we leave right now, we can get there before the rush.”

Chinese Food!!

We followed his lead. Slowly, we threaded our way back through the crowd, away from the line of buses now shaking ever more violently. We had just reached the sidewalk and taken a few steps onto Lafayette Park when we heard commotion breaking out behind us, screams, people running. A volley of tear gas cannisters flew out from the White House grounds, over the busses and into the crowd. They exploded. Sparks and smoke rose sharply in the air. People ran, scattered, as the gas spread. We ran too, but we were in front of everyone else – still close enough to get a good whiff of the tear gas, but not enough to be trapped.

And yes, we eventually did make our way to that Chinese restaurant and got a table before the crowd.

Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about that day in Washington, D.C. I’ve tried to turn it into a funny story for the family, how I learned my lifelong appreciation for Asian food. The spot where our group was tear-gassed in May 1970 was barely a block away from where police under President Donald Trump in June 2020 would unleash tear gas to clear demonstrators from around Lafayette Park to make way for a photo op in front of Saint John’s Church, just across the street. This time, the demonstrators were protesting the shooting of George Floyd and calling for racial justice. Circumstances were different, but the parallels were hard to miss: the anger, the eagerness for confrontation, the resulting acrid smell of gas.

Yes, we were right to be in Washington, D.C. that day in 1970 protesting the Vietnam War and the Kent State shootings. But that only scratched the surface. Were we, the protestors trying to knock over that bus in front of the White House, innocent victims of the National Guard or whoever launched that tear gas attack? Hardly. They were defending the White House, doing their job and, that day, doing it well. It was our side that picked the fight. Nobody was killed or seriously hurt. Nobody lost their right to free speech. How different this was from June 2020 when it was Donald Trump’s White House, the government side, that launched the unprovoked attack to clear Lafayette Park even though a pre-announced curfew had not yet gone into effect and nobody had been threatened.

But the point that stuck with me most deeply from 1970 was about the leaders. On one side were the loud people on the street in front of the White House egging on the mob, urging it deliver those wooden boxes, charge the White House, knock over buses, storm the grounds, oblivious to the risk the some of us could be shot, beaten, or gassed. And for what purpose? A headline? A thrill? A good time? A virtue play?

Then on the other side was Professor Strauss. I’m embarrassed to say that I was too naive that day to appreciate it, but Professor Strauss was teaching us something important in luring us away from the fight with his suggestion of Chinese food: how an actual adult demonstrates leadership in a tense situation. Seeing the dangers, he had recognized his duty to protect his students and was showing us how to withdraw gracefully before things got totally out of hand. It involved saying no, drawing limits, recognizing dangers, and having the discipline to act in a timely way.

I wish I had gotten to know Professor Strauss better back at Brown University. I never took another course in Applied Mathematics. Computers were still too futuristic for me back then; Psychology and History became my focus. But when I look at leaders, even today, be it politicians, candidates, or anyone else, the standard he set still lurks in my mind. Yes, Chinese food. How about Moo Shoo Chicken tonight?

Brown University decided to cancel its final exams that year and give every student a “Satisfactory” passing grade in all their courses. So it went on hundreds of campuses. But the wave of college protests that spring didn’t end the war. If anything, it marked a high point for student protests. After that, campus actions felt increasingly pointless and started getting smaller. Public opinion turned negative.

As for me, seeds of my future were being planted. After graduating college in 1973, I came to Washington, D.C. to start law school, drawn in great part by the next major political melodrama of that era, the Watergate scandal, reaching fever pitch with televised hearings a few blocks away before the Senate Ervin Committee. Soon I would start working there on Capitol Hill, as an intern, then a Committee Staff Counsel, then as an agency administrator, and on from there.

The 1960s were complicated, confusing, before even starting with all the drugs. Failing to have understood them in real time is no embarrassment for anyone. But for people my age, we Baby Boomers, those were our formative, coming-of-age years. They shaped us for good or ill – all the controversy, drama, and change – and not always in obvious ways.