We Rhode Islanders pat ourselves on the back a lot, including when it comes to the Revolution. But did the colony (and later state) really matter much in bringing about this major change in American life? Was Rhode Island, as historian Florence Parker Simister wrote, in “the fire’s center.” With the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence coming soon, let’s look at the arguments.

We can start with an excerpt from a history of the state written by William McLoughlin, long-time historian at Brown University:

Stubborn, pugnacious, and cocksure, Rhode Island rushed pell-mell toward revolution after 1764. Its people were more united, its leaders more outspoken in favor of independence than those of any other colony. In open disobedience, it was the spearhead of the Revolution. It was the first colony to resort to armed resistance, to call for a Continental Congress, to renounce allegiance to the king, to create an American naval force.

All of that is true. Nevertheless, a simple reading of history suggests that the state really didn’t matter much for achieving independence. To get there, the colonies had to do two things:

1) Resolve to become free of Britain and take up the responsibilities of self-government; and

2) Convince the British empire to end hostilities and allow us to become independent.

Rhode Island had already largely achieved the first goal by 1764, but it was too small to achieve the second goal on its own. So the key question is less about what Rhode Islanders did for themselves, but how much they led the other colonies toward the first goal, and then together achieve the second goal.

We Didn’t Start the Fire

In that light, it’s certainly true, as McLoughlin says, that the colony’s leaders believed more strongly in independence than those elsewhere. They appreciated easy access to British imperial ports, while reacting badly to any interventions from London. But the British overlords tended to see Rhode Island as too small to make a fuss about. In 1775 it still had only 60,000 inhabitants, far smaller than Massachusetts (320,000) or Virginia (525,000), and smallest of all the thirteen colonies except for Delaware (42,000) and recently chartered Georgia (27,000).

Besides, King Charles II had granted Rhode Island an unusual charter in 1663. Understandably antagonistic toward Puritans for beheading his father, and favoring religious toleration, he not only preserved the colony’s separation from Puritan Massachusetts and Connecticut, both of which coveted its land — but also gave it near-complete autonomy. Rhode Island was one of only two American colonies to elect its own governor rather than live under a royal appointee (Connecticut was the other). London appointed only the local customs officer.

So, it was easy for later imperial officials to dismiss little “Rogue’s Island” as an outlier. Back in 1704, the chief justice of the New York colony had written to England that Rhode Islanders “did in all things as if they were out of the dominion of the crown.” King George III himself noted in 1774, “Rhode Island is a strange form of government.” But nothing changed. Disobedience in the much larger Massachusetts got far more attention in Britain.

A photo of the replica of the Royal Navy warship HMS Rose. John Millar of Newport was a driving force behind its construction (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Rhode Islanders’ extraordinary autonomy – quasi-independence — actually made them less eager to stir up trouble with the Empire. By the 1760s the colony included several prominent monarchists, the “Newport Junto,” who pestered London to revoke the unusual charter, install a royal governor, and generally treat the colony like all others. To keep inconspicuous, Rhode Islanders complained only mildly about a steep new tax on molasses imports for the all-important rum distilleries. They still protested this tax and other burdens, with Governor Stephen Hopkins writing one of the most daring (and reprinted) theoretical objections to British rule. Yet he and other leaders declined to press their objections, and they returned from the “Stamp Act Congress” in 1765 with little to show for themselves.

Indeed, Rhode Islanders showed no interest in building inter-colonial resistance to the empire. The first strong opposition came from Virginia, whose general assembly in 1765 passed the “Resolves” put forward by Patrick Henry. Most other colonial assemblies followed suit. Rhode Island issued similar resolves, and mobs here likewise harassed local royal stamp issuers until they resigned their office. But Rhode Island’s riots were no greater in number than those elsewhere, even if local officials worried about Newport mobs getting out of hand.

Parliament backed down on stamps and then on the Townshend Duties in 1767 – but mainly because the colonies had successfully boycotted British goods, and London merchants suffered from losing a big market. Opportunistic Rhode Islanders, especially in Newport, were the last to cooperate with non-importation, to the point that most other colonies stopped trading with us. People here were fine with independence in principle, but not if they could make an easy buck from defying what other colonies were doing – hardly the basis for colonial leadership or effective opposition to empire.

After a lull of a few years, events moved quickly from 1770. That’s when the British began a new push to enforce its rules on customs, including the one remaining item from the Townshend Duties, on tea. The trouble began not here but on the Delaware River. First, unknown sailors beat a prominent New Jersey customs collector investigating a vessel off-loading its cargo onto small boats (a common smuggling technique). For good measure, they also tarred and feathered an assistant collector, his son. Then in 1771 outside of Philadelphia, after a customs schooner captured a vessel accused of smuggling, a mob arrived, beat up the captain and crew, and stowed them in the hold. By the next morning, the captured vessel and its cargo had disappeared.

Yet little came of this outrage against imperial authority, because colonial resistance to customs was old news. Back in spring 1764, after all, the gunner of the old Fort George in Newport fired several cannonballs at the St. John, a customs ship accused of taking hogs and poultry without proper payment. In December that same year, the customs ship Maidstone arrived in Newport and began impressing local sailors to fill out its crew. By June, those interventions had grown so bad that a mob arrived at the docked schooner, seized one of its small boats, and burned it to ashes. Governor Samuel Ward regretted the seizure and promised to prevent future violence but insisted that the Maidstone free all the local sailors it still held. Royal Navy officials complained, but imperial officials did nothing.

So, our much-prized attack on the Gaspee was just one in a series of aggressions against imperial rule, and perhaps even predictable. Dismayed at persistent smuggling in Narragansett Bay, the Royal Navy in 1772 assigned that schooner to police the area. As the Gaspee made its way to Narragansett Bay, its captain, Lieutenant Dudingston, heard that angry residents of Martha’s Vineyard had just rescued a captured smuggling vessel and imprisoned the crew of the offending customs ship.

Nevertheless, Dudingston persisted, and soon proved such an annoyance, with legal and extra-legal harassment, that John Brown and other Providence merchants took advantage when the Gaspee ran aground off Warwick. They shot and wounded its belligerent captain (“the first blood of the Revolution,” as the Sabine Tavern marker says), evacuated the ship, and burned it down. While Dudingston recuperated, Warwick’s sheriff (also one of the attackers) arrested him for improperly seizing an earlier cargo. The Royal Navy had to pay a stiff fine to get him released.

This time the Empire was aroused enough to organize a royal commission of inquiry, which got nowhere because of insufficient local willingness to testify. But the commission had one notable feature that raised the stakes: it could ship colonial suspects to England for trial. Why the change? Lawlessness seemed to be breaking out across the continent, from the Ohio Valley to South Carolina, and the Gaspee was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Here is the main evidence for the claim that the Gaspee attack brought on the Revolution. The creaking British empire wanted to make a point, and colonists everywhere objected that the King had thus infringed on the ancient English right of trial by a jury of one’s peers. But the commission was actually pretty milquetoast. No trial ever took place, as the commissioners couldn’t find any credible witnesses to testify in Rhode Island.

As Nick Bunker points out in his account of the British empire, only a hardline response that revoked Rhode Island’s charter and blockaded all of southern New England could have prevented the region from moving to independence. Some officials did call for stiff reprisals. But overall, the mainland colonies were just too marginal to the Empire for its officials to move decisively in 1772.

Even if the bold commission had mattered much for the revolution, Rhode Islanders weren’t the main actors. Characteristically, the loudest complaints came not from here, but from Virginia, whose leaders set up the intercolonial committees of correspondence that soon spread to every colony, including Rhode Island. Those committees did matter and were in place by December 1773 when the colonists in Massachusetts finally did something truly outrageous: dumping a large shipment of imperial tea into Boston Harbor. Meanwhile Rhode Island’s “neutral” governor, Joseph Wanton, tried to forestall confrontation.

From the Boston Tea Party came the Intolerable Acts, the First Continental Congress, the battles of Concord and Bunker Hill, forming an inter-colonial army, and the rest of the Revolution. Despite what the 2022 exhibit at the John Brown House suggested, the Revolution flowed not from the Gaspee attack, which the British decided mostly to overlook, but from the actions of the large colonies of Virginia and Massachusetts.

The Gaspee attack was hardly the first act of colonial aggression against the British, or even the first shot fired at imperial troops – the Newport cannon fire in 1764 preceded it. It was just the most noticeable aggression for British ministers to deal with, at a time when they were beset by drought and smuggling at home, depressed financial markets, and potential war in the Baltic. Perhaps in calmer times the Empire would have reacted forcefully, but the outcome would likely have been the same.

Jumping ahead to 1776, it’s true that the Rhode Island’s General Assembly voted in May to stop requiring officials to affirm allegiance to the British King (not quite the same as formal independence). But the Continental Congress had already largely decided to go for a full break by then, so the move was irrelevant to the great Declaration of Independence two months later. Here again, Congress paid far more attention to the large colonies, not Rhode Island.

We Didn’t Lead in the War, Either

Given its small size, Rhode Island was never going to be a major factor in forming the army. It’s true that people here led the way in creating the Continental Navy. The Rhode Island General Assembly sent a resolution to Congress requesting it to form a navy, which was done. Esek Hopkins (brother to Stephen), one of Brown’s regular ship captains (including for a disastrous slave trading voyage), became the first commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy.

For all his devotion to the Revolution, however, Brown put his personal profit above the country’s. He invested heavily in privateering rather than supporting the fledgling navy. He saved his best ships for the former and gave the navy only his mediocre vessels. He charged what an aide to General Washington called an “exorbitant” price for gunpowder that one of his privateers had captured from the British garrison in Surinam.

As for Commodore Hopkins, he effectively lasted less than a year. Hampered by sailors preferring to work for privateers rather than the navy, he accomplished little, and the little American navy was a non-factor in the war. Privateering was a factor, in raising the cost of sending British forces across the ocean, but it was not decisive, and in any case Massachusetts and other maritime colonies sent out privateers as well.

Rhode Islanders did fight in the major land battles of the war, from Bunker Hill to Yorktown, but with no special renown. Nathanael Greene of Coventry became what many have called General Washington’s “right-hand man,” and he skillfully frustrated the British southern strategy in 1780 and 1781. Even British historians have called him the best tactical general on either side in the war. But by 1780 British investment in the fight was already fading, stung by the great defeat at Saratoga in October 1777 and the entrance of the French soon after. Greene had done little before then and had blundered badly in leading troops during the evacuation of Manhattan in 1776.

The remains of a Revolutionary War era fortification in Middletown (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

When Greene took over the southern command, the war’s outcome was still in doubt. But the Empire, focused on its longstanding enmity with France and deeply concerned about losing its valuable Caribbean possessions, seems to have largely given up on subduing the northern colonies. General Cornwallis as well as the British foreign ministry hoped mainly to hold the supposedly more loyal areas south of Maryland. Greene’s brilliant maneuvers, with help from Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion and other southern irregular leaders, likely brought on the fateful battle of Yorktown sooner than otherwise. But the outcome of the war probably would have been the same without him.

Perhaps also relevant is that Greene largely abandoned Rhode Island after the war. He accepted a plantation from grateful southerners, moved to Georgia, and became a slave-holding planter, before his early death from heatstroke in 1786.

Newport’s Missed Opportunity

It’s true that Rhode Island could have played a decisive role. In December 1776, British forces occupied Newport and Royal Navy warships established a blockade of Narragansett Bay. Over the next year and a half, Rhode Islanders did little to harass or threaten the occupation. The rebels fortified Providence, removed coastal resources from British raiding parties, and carried out an impressive kidnapping of British general Richard Prescott. But for the most part, they sat back and allowed the British and some remaining loyalists to gradually despoil the city by the Sea. Major General Joseph Spencer (from Connecticut) led an attempt by New England states to capture Newport in October 1777 and more than 10,000 New England troops gathered in Tiverton, but the expedition was called off due to lost secrecy, leading to Spencer’s removal.

Only in August 1778, did the rebels finally do something, in the Revolution’s only battle on Rhode Island soil. A promising joint invasion of Newport with the French navy failed miserably when a major storm dispersed most of the ships, and British forces seized the opportunity to counter-attack rebel forces that had retreated to Portsmouth. Only rearguard action in Portsmouth, including a valiant stand by the integrated Rhode Island First Regiment and other Continentals, saved hundreds of troops from being wiped out. If the campaign had gone as planned and allied troops had captured the British force, the war might have ended three years early.

However disastrous for the city, the Newport occupation had two positive benefits for the Revolution. It foolishly kept British forces in New England when they might have assisted the Empire in the all-important mid-Atlantic region. And the First Regiment’s bravery under fire helped to begin to overcome white Americans’ deep-seated racism against people of African heritage.

French soldiers debark from their ships at Long Wharf in Newport, July 11, 1780 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

We Sat Out the Crucial Move to Preserve the Revolution

Winning the war was only the first step – now the new states had to sustain their independence. Rhode Islanders were satisfied with the wartime Articles of Confederation, but these proved a thin reed for preserving the fragile alliance of states and defending its land against jealous European powers. When Congress called a constitutional convention in 1787 to amend the Articles, Rhode Island was the only state not to send any delegates. When the convention went further and drafted an entirely new federal constitution, the farmer-dominated Rhode Island General Assembly denounced the move and refused to ratify it.

For over a year, while other states ratified the document and it became law, the General Assembly explored ways for the state to become a free-trading enclave surrounded by the American republic. Statia, the Dutch-controlled free port (and slave-trading mart) of St. Eustatius in the Caribbean, was a favored model, though it still depended on Dutch protection. Only in 1790, when the new United States threatened to impose duties on trade with Rhode Island, and merchants in Providence and Newport sought to secede from the state, did the General Assembly relent and allow a vote that narrowly ratified the federal constitution.

Joining the Union proved crucial for the state’s political as well as economic development. Besides giving Rhode Islanders’ open access to American markets for its burgeoning manufactures, the Union likely helped promote democracy in the long run. Prosperous manufacturers were inclined to hoard political power for themselves, especially against non-Anglo-Saxon immigrant communities. But participation in the American republic helped to prevent what might otherwise have become an oligarchy.

But We Were Still Essential

Nevertheless, Rhode Islanders can take pride in their participation in the Revolution. We just need to look deeper into what the Revolution was all about: the majority of people resolving to take up the responsibilities of self-government. In the 18th century, most Europeans still followed the medieval hierarchy. The world, they thought, consisted of God on high, then the King, then the nobility, then the gentry, then commoners (with whites ahead of people of color), and then animals. Hardly anyone thought of humanity in general. Colonial gentlemen wrote about traveling “alone” when accompanied by a servant, because only people of their class mattered.

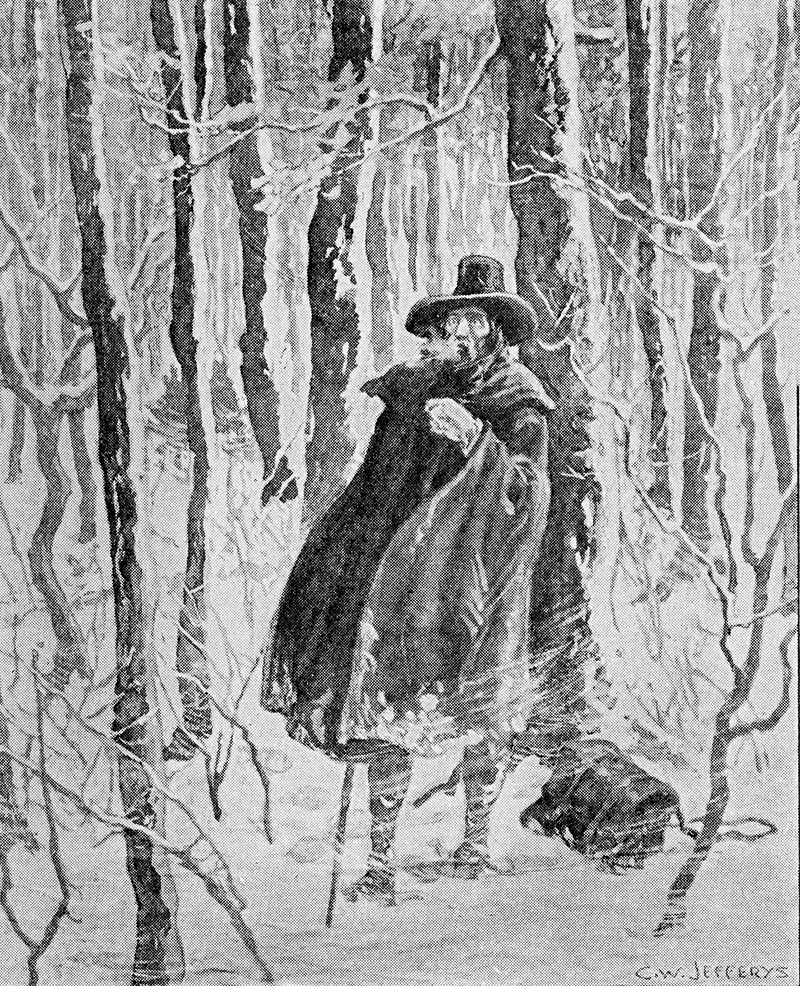

The Revolution came with a severe critique of hierarchy – and Rhode Island clearly led the way here. A century earlier, Roger Williams had taken Protestant ideas to the next level and preached “soul liberty.” He was more than a brilliant thinker; he (and likeminded Anne Hutchinson) also managed to persuade hundreds of followers to join him in the wilderness of early Rhode Island. Among them was the clergy-diplomat John Clarke of Newport, who worked with Williams to secure autonomy in the Charter of 1663.

Surrounded by Puritan centralizers seeking to create a religiously monolithic and intolerant society, Rhode Islanders nevertheless insisted on individual freedom. We don’t have to say (as John Barry did) that Williams “created the American soul,” to acknowledge that his efforts helped lead to the Revolution.

Indeed, even as Puritans denounced Rhode Island as a “cesspool” of individual liberty, religious freedom and democracy, Williams’s example drove home vital lessons throughout the colonies. Our weirdly quasi-egalitarian approach, not Massachusetts’s Puritanism or Virginian gentility, became the dominant American culture. And that’s what won the Revolution. The result was hardly an egalitarian paradise, with stiff hierarchies of gender and race still in place. But much of the old deference had faded.

The British strategy against the rebellion depended on a crucial assumption: many, if not most colonists remained loyal to the King according to that hierarchy. Caught in that mindset, British leaders believed the troubles had arisen mainly from a few rebel hotheads and mobs that had intimidated the loyalists. They sought a quick victory to prevent a fratricidal conflict that would drain resources from the main colonial prize, those sugar-exporting islands of the Caribbean. So they planned a large military force to arrest the leaders and restore order, at which point the loyalists would emerge and take back control.

That didn’t happen, not in Massachusetts, not in New York, and not in South Carolina. Deep down, most colonists rejected the old hierarchy and preferred self-government. They may have known little about Roger Williams or the crazy charter, but Rhode Island’s example at least indirectly inspired them to believe a democratic republic was actually possible.

Roger Williams imagined as trekking through forests from Puritan Massachusetts to what is now Rhode Island

Time and again, British generals complained to London of paltry assistance from supposedly loyal colonials, while noting the impressive bravery of mere commoners in defending “their” land. British efforts to maintain its American colonies were probably doomed from the start of the war, thanks partly to Rhode Island.

Editor’s Note: John Landry and Christian McBurney are looking to organize local historians to write a series of essays on Rhode Island in the American Revolution. With the 250th anniversary approaching, we hope to highlight the findings of numerous books and articles written on the subject since the 1970s. Please contact Christian McBurney at editor@smallstatebighistory.com if interested.

Sources

William McLoughlin, Rhode Island: A History (Norton, 1978).

Florence Parker Simister, The Fire’s Center: Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era, 1763-1790 (R. I. Bicentennial Foundation, 1979).

Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (Knopf, 1992).

Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution (Simon & Schuster, 2006).

David Sherman Lovejoy, Rhode Island Politics and the American Revolution, 1760-1776 (Brown University Press, 1958).

Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (Oxford University Press, rev. ed., 2005).

Nick Bunker, An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America (Knopf, 2014).

Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Westholme, 2022).

Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Westholme, 2011).

Robert W. Smith, “Algiers or St. Eustatius: Foreign Affairs and the Ratification of the Constitution in Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Summer/Fall 2018), 48-70.

John Barry, Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty (Viking Penguin, 2012).