As I poked around the photography division of the Navy History and Heritage Command last summer at Washington Yard in Washington, D.C., I was hoping to find more photographs for my second World War II Rhode Island book. Instead, I stumbled upon a scrapbook containing a remarkable collection of photographs taken from a Navy biplane from 1924 to 1934. Several of them were scenes of Narragansett Bay and Newport. I knew almost immediately that they were a hidden treasure and that more than just viewers of smallstatebighistory.com should view them. I decided that I would try to get them seen by the widest audience possible. I offered them to the Providence Journal as an article. I was not surprised when the newspaper agreed to run some of them. However, I was surprised that the article on the photographs, written by the talented Donita Naylor, ran in the upper fold on the front page of the December 28, 2018, edition (well, it being the holiday season, it was a slow news day). On the same day, the identical article (albeit with some different photographs) appeared on the front page of the Newport Daily News.

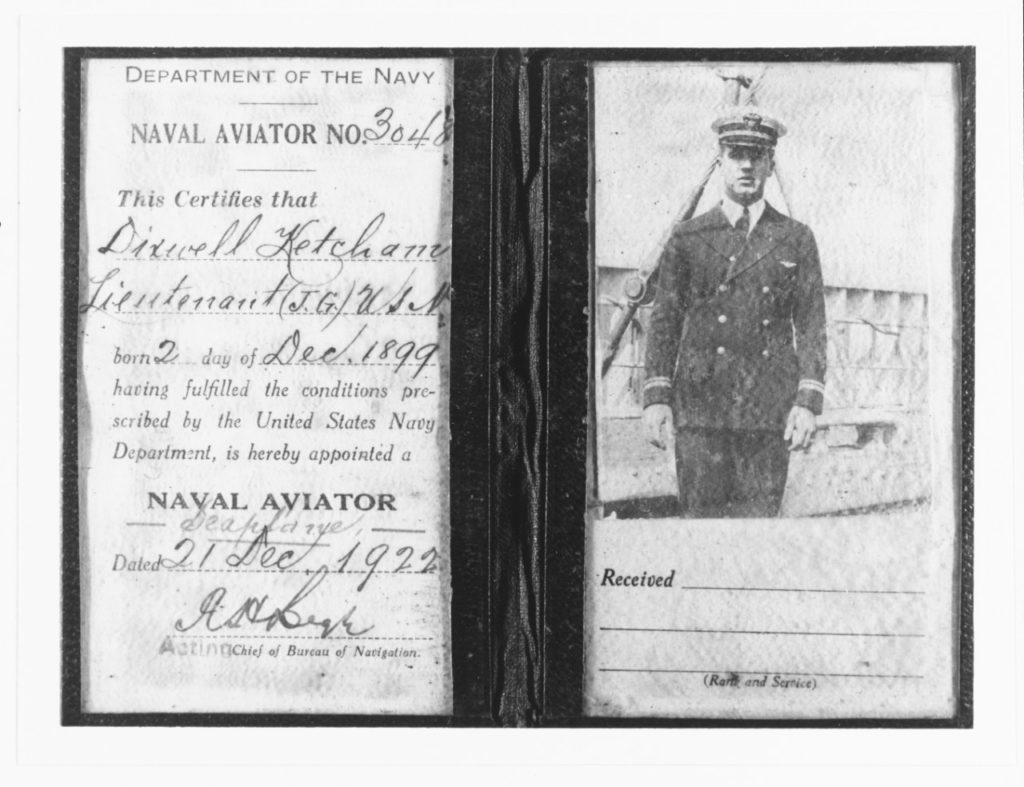

Naval aviator certificate, dated December 21, 1922, making Dixwell Ketcham’s appointment as naval aviator number 3048.

The Providence Journal and Newport Daily News articles and website versions could not include all of the photographs I had collected. In this article, I show all of them of Rhode Island. They follow this article.

The photographs can be viewed in different contexts. For one, they are about the photographer and Navy flier, Dixwell Ketcham, and his experiences as a pilot in the 1920s and early 1930s. It is also about the early days of naval aviation using bi-winged seaplanes, called floatplanes. There was tremendous risk involved, but excitement too about being on the cutting edge of technology. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the photographs is their superb quality. That part of the story is about cameras built specially for aerial photographs.

After the Wright Brothers in 1903 took their first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, it was not until 1909 that the Navy Department began to treat naval aviation seriously. By 1910 the Navy’s first aviator completed his training and the first flight from the deck of a Navy cruiser occurred. In January 1912 the Navy established the first naval air station at Pensacola, Florida. When the U.S. entered World War I, it had only 48 qualified naval aviators and 54 planes. Virtually all of the aircraft used by the Navy in the war were bi-winged seaplanes built only for reconnaissance. Generally, each cruiser and battleship carried at least one or two aircraft. The one Navy base in New England during the war was at Squantum, Massachusetts.

This was the world Dixwell Ketcham entered. Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1899, he enrolled at the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1916 and graduated in 1920. He joined the new and exciting field of naval aviation. While not still in its infancy, it was still immature. After training to fly at Pensacola, in December 1922, at the age of 22, Lieutenant (junior grade) Ketcham earned his appointment as naval aviator. He stayed with naval aviation for the rest of his career.

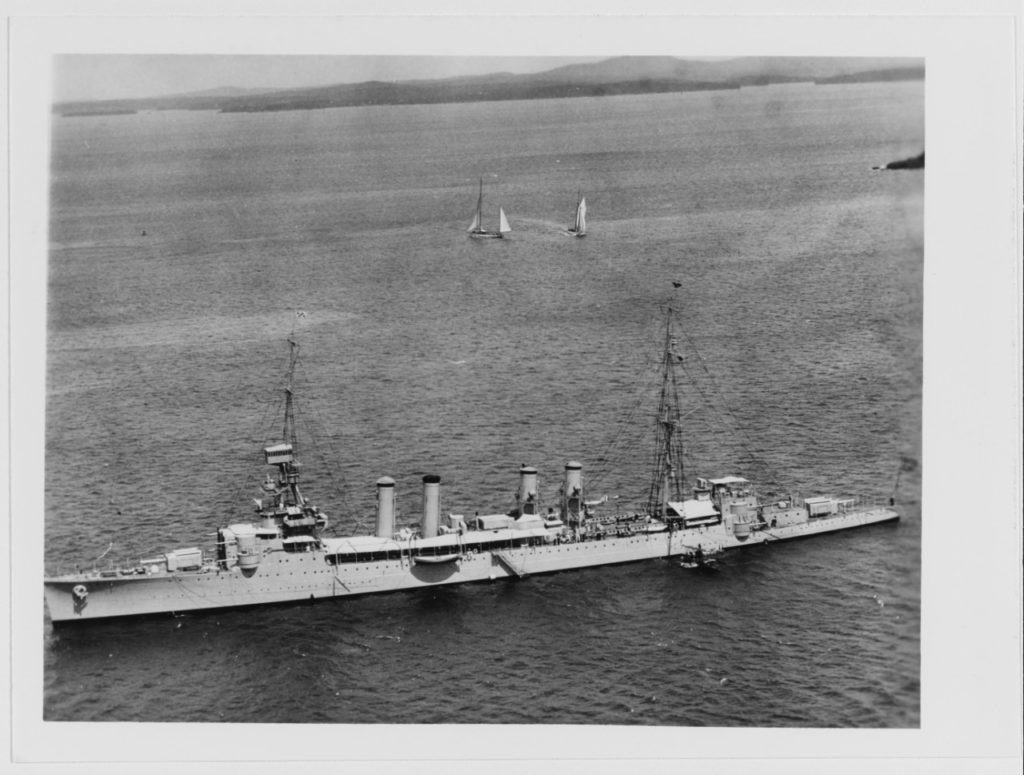

By 1924, Ketcham was an experienced pilot, typically sailing on the light cruiser USS Richmond. His plane was a floatplane that would be launched from the cruiser by a catapult mechanism. It could land on the water on its floats near to Richmond and taxi next to the ship’s crane. The crew, using a cable winch and reel mechanism, would then lift Ketcham’s plane back onto the deck. If Ketcham need to fly again, the winch and cable would be used to hoist the floatplane back on the catapult. In 1924, catapults launching floatplanes were powered by gunpowder. The floatplane could also take off on the water.

The floatplane had two open cockpits. The flier flew in the front cockpit, the observer or photographer in the rear cockpit. It must have been quite an experience flying over Narragansett Bay, with the wind whipping over the pilot and whistling around the struts and wires holding the aircraft’s two wings together.

Ketcham’s catapult-launched seaplane was typically a Vought O2U-1 “Corsair” floatplane. Its main purpose was reconnaissance—spotting and observing the enemy’s fleet. These floatplanes were sometimes called scout planes. They could also be used as artillery spotters—a cruiser’s eight-inch guns could fire artillery shells about ten miles. The Corsairs were built at nearby Stratford, Connecticut.

A Vought O2U Corsair floatplane flying at sunset in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The crew has just dropped a torpedo as part of an exercise. The photographer caught the torpedo, which was likely made at the Newport Naval Torpedo Station, in midair.

The Navy began having pilots use cameras on floatplanes so that they could take aerial photographs. In addition to the field of aviation, the field of aerial photography was also in a relatively young stage. The quality of many regular cameras was poor. Taking an aerial photograph with a camera when on board a light bi-plane that would vibrate from the running engine and get pushed around by winds often did not generate high-quality photographs. But the Navy could afford the best cameras that money could buy. Ketcham was provided with one of these cameras, based on the incredible quality of his photographs.

Rob Doane, curator at the Naval War College Museum, thinks that the type of aerial camera Ketcham used on his floatplane was either a Sherman Fairchild K-3 or K-5. Doane stated that by the 1920s and 1930s, these cameras had solved a lot of the earlier problems of vibration and focus. The cameras were large, which increased the photograph’s depth of field. Ketcham would have held the large and bulky camera sitting in the rear cockpit (cameras in World War II would be affixed to the aircraft).

Ketcham took photographs wherever he went on board the light cruiser Richmond. His locales included Havana and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; Panama City, Panama; and St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. In those days, the U.S. Navy often spent winters training out of ports in the Caribbean. Happily for us, he also visited Newport and Narragansett Bay. Of course, the Navy had an important presence in Newport, highlighted by the Naval Training Station for new recruits, the Naval War College for officers, and the Naval Torpedo Station.

The light cruiser USS Richmond, at anchor, around the late 1920s. Note the floatplane at its side in the water. Another floatplane is secured to the ship behind the second smokestack. Ketcham was often assigned to this warship.

The features that leap out from each photograph are its sharp focus and depth of field. Many of the photographs may be the best aerial photograph ever taken of its subject.

Consider, as an example, the photograph of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis at anchor in New York Harbor. The sleek vessel was the pride of the U.S. Navy when it was christened in 1932 and would serve as the flagship of the Pacific Fleet during World War II. In Ketcham’s photograph, at the mainmast (at the ship’s stern) can be seen a flag flying the presidential seal, indicating that President Franklin D. Roosevelt is on board. This photo must have been taken during one of the three cruises that Roosevelt made with this ship, in 1933, 1934, or 1935. Given that Ketcham was present in New York Harbor on Navy exercises in 1934, it was likely that year. The three star flag flying from the foremast signals there is also a three-star admiral on board. (According to the August 15, 1934 edition of the Providence Journal, Indianapolis visited Narragansett Bay, along with four other heavy cruisers and a host of destroyers, although Ketcham’s collection does not have any photographs from that visit.)

A Vought O2U-1 Corsair floatplane suspended over a ship’s catapult by a cable winch and reel mechanism during the later 1920s

Two of Ketcham’s fellow naval aviators, unidentified, while in flight, viewed from the observer’s cockpit

Two machinists (right Crawford, left Auser?), one leaning on a propeller. They maintained and repaired the floatplanes on board Richmond. The young men were at the cutting edge of technology at this time and they look like they know it

Naval aviator takes photograph from an open, rear cockpit holding a Sherman-Fairchild K-3A Camera (Smithsonian Institution)

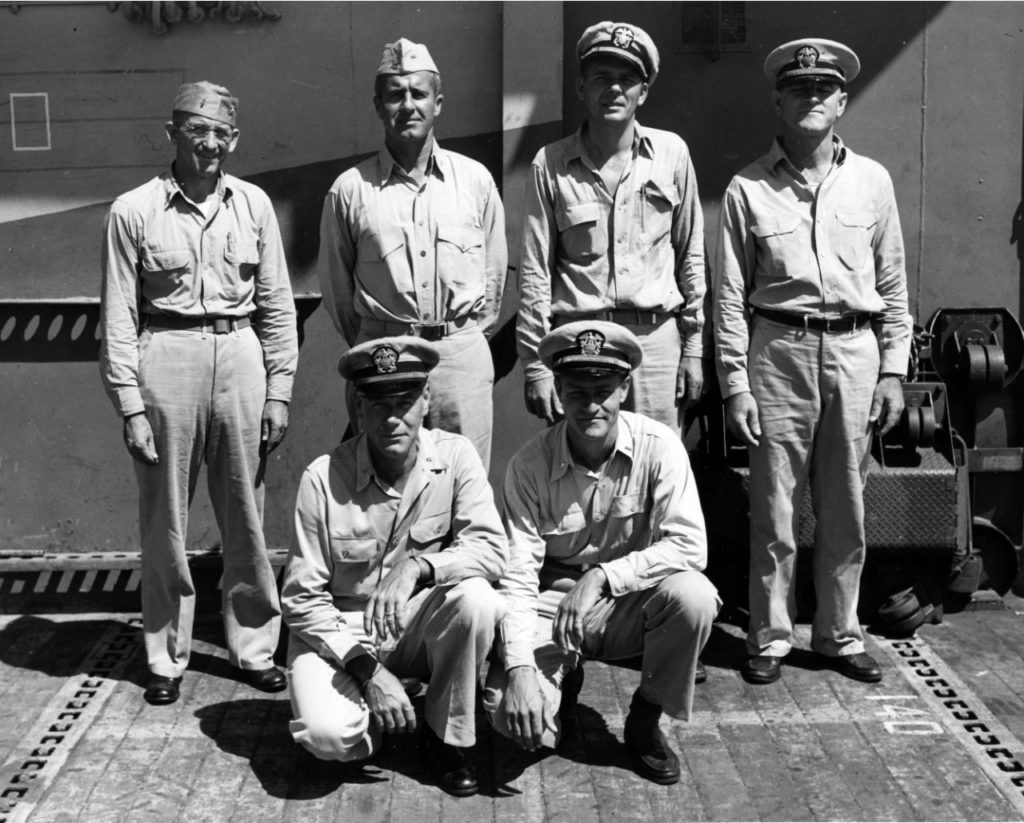

Admiral Dixwell Ketcham (second from left, standing) on the escort carrier Block Island in the Pacific. Immediately after Japan’s surrender, he supervised the rescue of 1,200 American and allied prisoners at a Japanese POW camp on Formosa.

Already famous prior to the war, during the war Indianapolis delivered parts of the atomic bomb to Tinian Island in July 1945. Tragically, it was sunk on its return voyage by a Japanese submarine and its communications officers had no time to signal their location or fate. Hundreds of sailors went down with the ship, and hundreds more died in the next several days, many by shark attacks. Finally, a “flying boat” seaplane spotted some survivors and radioed nearby ships for help.

The incredible story of Indianapolis is well told by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic in Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man (Simon & Schuster, 2018). Interestingly, Ketcham’s photograph of the doomed ship is better than any of the ones of it in the best-selling book.

I would hazard a guess that the following are the best aerial photographs ever taken of their subjects: Jamestown’s East Ferry Landing; the warship in Narragansett Bay; the Mount Hope Bridge; and the Newport mansions other than Miramar.

One aspect of the photographs of the Newport mansions jumps out: the beautifully-manicured lawns and gardens. This was a time when the wealthy still owned substantial Newport mansions; the Great Depression and high taxes had not yet taken their toll. Ketcham too was impressed, based on the number of coast-side mansions he photographed.

Which of the Rhode Island photograph is my favorite? It is a tough choice, but I would choose the one showing sixteen biplane floatplanes floating at Potter’s Cove off Jamestown. This is a sight that the world will never see again—there just are not enough surviving floatplanes. There was only a small window of time in world history, and a few places where such a scene could have even occurred. One wonders how it came to pass that so many floatplanes visited Narragansett Bay at one time. Presumably, many of the Navy’s cruisers on the East Coast must have rendezvoused at Narragansett Bay. Next to the floatplanes is the USS Wright, a tender that provided fuel and other supplies to floatplanes. This photograph is one of the few Rhode Island photographs in Ketcham’s collection that is dated—in this case, 1924. That date is prior to the year the Navy launched its first aircraft carrier in 1927. A close second for my favorite is the photograph of East Ferry Landing at Jamestown.

What happened to Dixwell Ketcham in World War II? As with a number of early naval aviators, he commanded aircraft carriers in the Pacific theater. He saw action at the Gilbert Islands (1943) and the Marshall Islands Campaign (1944). He ended up as rear admiral of an aircraft carrier task force, using the escort carrier Block Island as his flagship.

Perhaps Ketcham’s most memorable role occurred shortly after Japan’s surrender. Navy command feared that American and other Allied prisoners of war were at risk of being killed by Japanese prison guards eager to get rid of the evidence of their war crimes. This risk became reality in a few instances. But Ketcham prevented any such occurrence at the island of Formosa by quickly diverting his carriers and having aircraft pilots drop pamphlets with instructions for the guards and supplies for the POWs, and then having his fleet rescue and pick up the 1,200 survivors. Ketcham passed away at the age of 93 in 1993 and is buried at Palo Alto, California.

Enjoy the photographs!

[Banner image: East Ferry Landing for the Jamestown—Newport ferry, circa 1930 (Dixwell Ketcham Collection, Photography Division, Navy History and Heritage Command)]Credits for Identifying Subjects in Photographs:

Unless otherwise provided, all of the photographs below are from the Dixwell Ketcham Collection, Photography Division, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

Most of the photographs below can be viewed at the Naval History and Heritage Command’s website. Go to www.navy.mil (click on Naval History & Heritage Command; then on Collections; then Photography; search for: Ketcham). The following are not posted at that website: the Newport mansions; the Mount Hope Bridge; East Ferry Landing at Jamestown; and the heavy cruiser in Narragansett Bay.

Ingrid Peters, Deputy Director and Director of Education, and Bertram Lippincott III, Librarian and Genealogist, of the Newport Historical Society identified the Newport mansions and Luce Hall at the Newport Naval War College. Robert Doane, Curator of the Naval War College Museum, provided information for the Luce Hall photographs, the heavy cruiser in Narragansett Bay, the battleship in New York Harbor, and the Indianapolis. John Peixinho identified homes in the photograph of Bailey’s Beach (some I did not even mention). Russell DeSimone spotted Miramir, which I confirmed with an online search of period photographs. The Providence Journal staff concluded that the ferry landing was on the East Side, which I confirmed by doing a search of period postcards and photographs. I obtained the information on the floatplanes and Richmond from the Naval History and Heritage Command website.

The captions for the Newport mansions shown below are mostly derived from captions of photographs of the same mansions (but not as good quality) at the Robert Yarnall Richie Photograph Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University (the online digital collections can be accessed by searching in Google for the name of the house, Newport, and Yarnall).

Dixwell Ketcham’s Rhode Island Aerial Photographs and More:

(To enlarge the photograph, click on the photograph; to return, click on the x in the upper right corner)

Sixteen Navy floatplanes moored at Potters Cove off Jamestown. To the left is the USS Wright, the tender vessel that provided the floatplanes with fuel and serviced them. To have so many floatplanes in one location, there must have been several cruisers in Narragansett Bay at the time (1924). Note the rural scene in Jamestown.

Jamestown Ferry landing on the East Side of Jamestown. The ferry is inside the pilings, perhaps taking passengers on board.

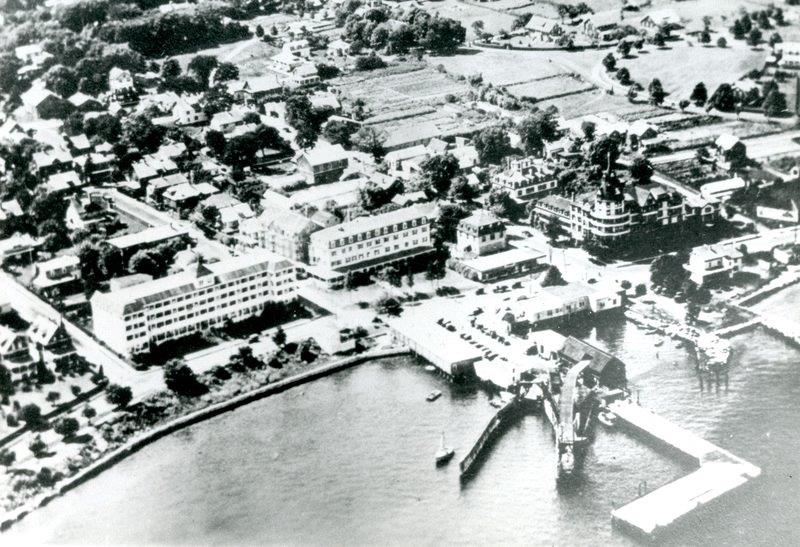

Close up of Jamestown landing on the East Side of Jamestown. From left to right, the major hotels fronting the shore are Hotel Thorndike, Gardiner House, and Bay View Hotel (with castle-like turret on the right).

Jamestown Ferry Landing showing Hotel Thorndike, Gardiner House, and Bay View Hotel. Taken in 1930, but NOT by Ketcham. It is a decent aerial photograph, but is not of the same high quality as Ketcham’s photograph. It is here for comparison purposes only (Providence Library Digital Collections)

The recently-constructed Mount Hope Bridge, with Bristol at the bottom of the photograph and Portsmouth at the top. It was dedicated on October 24, 1929. It is possible this photo was taken even before it opened for automobiles, although it appears one automobile is on the bridge just above the edge of the Bristol coast. The Musselbed Shoals Lighthouse, destroyed in the 1938 Hurricane, is shown on the right (west) side of the bridge near Portsmouth.

A heavy cruiser moored in Narragansett Bay, either the USS Pensacola or USS Salt Lake City. Note the two floatplanes just behind the far smokestack, and the cable and winch mechanism that would lift them from the water just in front of the far smokestack.

Luce Hall, at the Naval War College on Coasters Harbor Island. Note the three separate stairways to classrooms and the artillery piece in front. At the rear of Luce Hall is Mahon Hall. Founders Hall is next door with trees in front.

Cadets marching on Dewey Field at the Naval Training Station on Coasters Harbor Island. The Commandant’s residence is to the north of the marching cadets. Naval War College buildings Luce Hall and Founders Hall can also be seen at the left.

A tranquil scene of Newport Harbor, with the city of Newport sprawling in the background. Ida Lewis Rock Lighthouse sits in the lower right portion of the photograph. It became the Ida Lewis Yacht Club in 1928. Around this time, a boardwalk was built connecting it to Aquidneck Island. This photograph was likely taken prior to the date in 1927 when the lighthouse ceased its regular operations and the light was transferred to a thirty-foot steel tower placed in front of the dwelling and automated.

Bailey’s Beach, the private exclusive beach club for Newport’s elites. It must be summer as beach chairs are set out in rows. In the upper middle is Land’s End, once owned by Edith Wharton. To the right of Land’s End, south of the road leading to water’s edge, are the ramparts of Lippitt’s Castle that would later become The Waves. Rough Point is visible in the upper left corner. After the 1938 Hurricane destroyed the pavilion and cabanas, the road alongside Bailey’s Beach was moved to the east, a bit away from the beach, and a new complex was constructed.

F. Frazier Jelke’s Eagle’s Nest at 222 Ocean Avenue in Newport. Eagle’s Nest was built in 1922-24 for investor Ferdinand Frazier Jelke, who owned the estate at the time of this photograph. The French farmhouse-inspired cottage overlooking the Atlantic Ocean was designed by architect William T. Aldrich; Henry Davis Sleeper designed the interiors and Olmsted Brothers the landscape. On the third anniversary of the opening of his new summer home in 1925, Jelke hosted a dinner for 400 of Newport’s social elite. Jelke’s family from the Midwest originally made its money from manufacturing margarine.

Miramar, with its tended gardens. Miramar is a 30,000-square-foot French neoclassical-style mansion still bordering Bellevue Avenue and overlooking Rhode Island Sound. It was intended as a summer home for the George D. Widener family of Philadelphia, before Widener and his son Harry died aboard the Titanic. The widow and mother, Eleanor, continued the project, and Miramar was officially opened on August 20, 1915. Eleanor married Dr. Alexander Hamilton Rice, Jr., on October 14, 1915, and the couple continued to use Miramar as a summer home. After the death of his wife, Dr. Rice enjoyed the use of Miramar until his death in 1956, at which time ownership reverted to his wife’s children, who sold the estate to a private school. It was sold in 2006 to an investor for a reported $17.6 million.

Shamrock Cliff (now Ocean Cliff) on Ridge Road. It was built in 1894-1896 for Baltimore steel industrialist G. M. (Gaun McRobert) Hutton and his wife (Celeste (Winans) Maguerite). It was constructed on the site of the villa built in 1864 for Arthur Bronson of New York and his wife, and it overlooks Narragansett Bay. The building contractor for the Romanesque-style Shamrock Cliff was McNeil Brothers of Boston; Peabody & Stearns were the architects and Olmsted Brothers the landscape designers. The estate passed from the Huttons to their daughter, Elsie Celeste Hutton, who sold Shamrock Cliff in 1958. The estate eventually was converted to a hotel, resort and apartment complex now known as OceanCliff.

Harbor Court, the Brown Estate, at 5 Halidan Avenue. Harbour Court was built in 1904-1906 by Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson (Boston) for the widow of John Nicholas Brown I, Natalie (Dresser) Brown. The estate was located on property Mrs. Brown purchased in 1903 from the heirs of Chicago judge and industrialist Hugh T. Dickey. It was modeled for the most part after her brother-in-law’s ancestral seat in Normandy, Chateau d’Osmoy. Olmsted Brothers designed the landscape around the main house in 1914-1915. Harbour Court remained in the Brown family until 1987, when it was purchased by its current owner (reportedly for $4.5 million) by New York Yacht Club, which uses the building as its clubhouse.

A portion of the Navy’s fleet steaming in three parallel columns. Floatplanes typically had a scouting and observation mission and would search for enemy fleets

Battleship New York steaming, probably in New York Harbor (which explains the sailors lined up on the ship’s sides) in the early 1930s. It could be from 1934, as Ketcham attended that year’s fleet maneuvers in New York Harbor.

Heavy cruiser Indianapolis in New York Harbor. Note the U.S. Presidential Flag flying at the stern of the ship at the foremast, indicating that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was on board. This would date the photo to 1933, 1934 or 1936. Another flag indicates that a three-star admiral is also on board. It is probably from 1934, since Ketcham attended that year’s fleet maneuvers in New York Harbor.