European immigrants were not the only people who filled the Midwest with farms. Plenty of Rhode Islanders went west, too.

By the late 1700s, the population in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut had pretty much reached its saturation point. Virtually all the land was cleared and settled. Parcels that had been divided for generations to make new homesteads for sons could not be divided further without creating lots too small to support a family.[1]

That was when waves of emigration started to carry Rhode Islanders to the north and west. After 1790, the population in rural Rhode Island decreased, principally as a result of the out-migration of “the discontented, the enterprising, the ambitious and the covetous.” The population loss in the three southern New England states between 1790 and 1820 has been estimated at 800,000.[2]

One of those waves of emigration came after the War of 1812, which had a devastating effect on New England’s economy. Just as the war ended, a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia filled the atmosphere with dust that blocked the sun. In 1816, “the year without a summer,” widespread and severe crop failures led to further economic decline.[3]

When New Englanders found out that the government was giving away land in Ohio that was level and relatively easily cleared, “Ohio Fever” spread quickly. “That alarming disease denominated as Ohio Fever continues to rage in many parts of New England, by which vast numbers are taken off,” the Bangor, Maine Weekly Register reported on July 5, 1817.

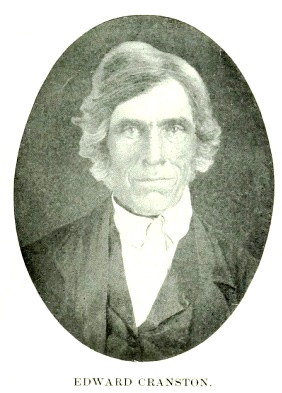

One of the victims of this strange new disease was Edward Cranston of North Kingstown. He is representative of the many Rhode Islanders who migrated to Ohio. His story was repeated by many Rhode Islanders. This article also extends Edward’s family story, as many descendants migrated to other parts of the country.

Probably about 1850. From Nelson W. Evans, A History of Scioto County, Ohio, (Portsmouth, Ohio, Author, 1903), 1:76.

The second son of Caleb and Sarah (Burlingame) Cranston, Edward Cranston was in his mid-20s when he went to Ohio.[4] Legend has it that he rode a horse there from Rhode Island.[5] By 1819 Edward had settled in Portsmouth, Ohio, where he would later be remembered as “one of the most forceful characters who ever occupied the stage of public affairs in Scioto County.”[6]

Scioto County is in southern Ohio, separated from Kentucky by the Ohio River. When Edward arrived, most of the county was still a wilderness. The first public road was opened in 1803, the same year that Portsmouth, the county seat, was platted[7] and the same year that the State of Ohio joined the Union. A traveler who stopped in Portsmouth in 1819 described it this way:

At noon, we reached the town of Portsmouth, in Ohio, at the mouth of the Big Scotia (sic); a considerable stream, said to be navigable upwards of two hundred miles towards the north. Portsmouth is an improving place, containing a court-house, a bank, several good taverns and stores, and more than one hundred houses, many of them of brick. We could get but few provisions here. [8]

Written accounts portray Edward Cranston as willful and domineering. His self-confidence seems to have asserted itself right away. In 1870, six years after he died, this anecdote about young Edward Cranston appeared in the Portsmouth newspaper:

In 1819 Edward Cranston was putting up a wool-carding machine in the neighborhood of Gallipolis, in a mill owed by a Frenchman named Thevenin, propelled by the waters of Raccoon Creek. While at work there Cranston boarded with the owner of the mill. [Thevenin] was a large, stout, two-fisted, fear-naught kind of a man, yet quite peaceable, quiet and inoffensive in a general way. When seated at the table Thevenin would fill his own plate with the best before him, and then pass the dishes containing the food to the girl waiting on the table; saying, “take dis away; [or] de boys want some of dis.” The old Frenchman practiced this to such an extent that Cranston was put upon short allowance and he resolved that as he paid for his board he would have enough to eat at least. The next time the Frenchman said “take dis away,” Cranston said: “Hold on, I’ll take some of that, if you please, before you take it away.” The dish was passed to him, with true French politeness, and that broke up taking dishes away before dinner was over or they had been emptied of their contents.[9]

Edward operated a wool carding mill in Portsmouth in partnership with a quirky Prussian immigrant named David Gharky. According to a county history, “These partners were par excellence the two most self-willed persons in the county at that time or any other time, but so far as posterity knows, they got along pleasantly.”[10] The first property conveyance in Scioto County recorded in Edward’s name is his 1820 purchase of the site of the carding mill, which later was called “the first manufacturing establishment of any consequence” in Scioto County.[11] That same year, Edward was the captain of a private militia company in Portsmouth.[12]

The Cranston Woolen Mill in Wheelersburg, Ohio. The date is uncertain, but it could be about 1845, when Edward Cranston still owned the mill.

Edward married in 1821, but his wife died only a few years later, after giving birth to two children who died in infancy.[13] In 1825, Edward married Sallie Whitcomb, a relative of the influential Young family who arrived in Scioto County from New Hampshire around the same time Edward had arrived from Rhode Island. Sallie’s uncle, Rev. Dan Young, a Methodist minister, served six terms in the New Hampshire legislature before coming to Ohio.[14] Rev. Dan and his brother John founded the village of Wheelersburg in Porter Township, a few miles northeast of Portsmouth.[15]

In 1828, Edward moved with his wife Sallie to Wheelersburg, then still a heavily-timbered wilderness, to operate a cotton carding mill owned by the Young brothers. Edward bought the mill in 1835, converted it to a woolen mill, and operated it until 1848, when he turned it over to his son Jeremiah.[16] It was said of Edward that he “exercised good judgment in making his investments, bought large tracts of land adjoining the village, and superintended the improvement of his property.”[17] By 1850, he owned the largest farm in Porter Township, 190 acres of improved land and 50 acres of unimproved land with a total value of $9,600.[18] His livestock, including 65 sheep, was worth $550. His farm produced 2,500 bushels of Indian corn, 200 bushels of oats, 130 pounds of wool, 150 bushels of Irish potatoes, 100 bushels of buckwheat, 260 pounds of butter, and 35 tons of hay in 1850.[18] The same year, his woolen mill, which had five employees, produced 5,000 yards of satinet and jean fabric worth $3,750 and 1,200 pounds of yarn worth $840.[19]

Scioto County was a predominantly Whig county, and Edward Cranston was a local Whig party leader. In 1830, he was appointed to fill a vacancy on the three-member Board of County Commissioners. He was elected to the board in 1832 without opposition, and re-elected in 1835, serving until 1838. A county history says of him, “He was a man of the strongest will of anyone who ever held the office. He ruled the Board and all in contact with him and did it well.” While he was a commissioner, the county constructed a new courthouse and a new jail, and built a bridge over the Little Scioto River.[20] On 3 January 1846, the Ohio legislature elected Edward to a seven-year term as an Associate Judge of the Scioto County Court of Common Pleas. He left the bench when the state’s judiciary system was reorganized in September of 1851.[21]

Edward and Sallie had nine children, four of whom—two sons and two daughters—lived to adulthood, according to a letter written by their son Benjamin in 1893.[22] The eldest, Narcissa, died in 1852 at the age of 26. Ruth, born in 1931, married George O. Wiggard, a native of Maryland. They lived at various times in Wheelersburg and in Kentucky, where George was in the woolen manufacturing business.[23] Jeremiah, born in 1827, became a partner in his father’s woolen mill in 1848 at the age of 21 and operated it until 1883, when he turned it over to one of his sons.[24] Benjamin, born in 1833, farmed 170 acres and had fourteen children with two wives.

In October 1862, a brigade of Union soldiers that was retreating across the Ohio River camped on the Cranston farm. The family offered hospitality to the officers and provided food for the soldiers. Edward made a claim to the quartermaster for the fencing the soldiers used for firewood and the field corn they ate— not the food the family provided for them or for the officers—but was coolly told that the Army had heard that Edward’s son-in-law George, then living on the farm, was a secessionist and that Judge Cranston was “no better.” The Wheelersburg correspondent for the Portsmouth Times, clearly miffed, wrote, “A little strange, is it not, that one of the first and simon-pure Republicans in the county should be charged with disloyalty.”[25]

It was Edward Cranston’s grandchildren, not his children, who inherited his itch to move westward. Twelve of Benjamin’s thirteen children who lived to adulthood became homesteaders, cattle ranchers or farmers in Cascade County, Montana, extending the Cranston family of Rhode Island further west across the continent.

Cascade County lies between a rich mining and stock-raising district and the agricultural basin of North Central Montana, where the plains meet the mountains. The Missouri and Sun rivers meet at Great Falls, the county seat. The Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled up the Missouri and through the present site of Great Falls in June 1805.[26]

Benjamin’s children were notable for their stature, “each of the seven sons being over six feet and the four daughters proportionately tall, and as fine specimens of physical manhood and womanhood as are to be found in any state,” according to the Portsmouth newspaper.[27] It may have been land that drew them to Montana. The Homestead Act of 1862 made land that had been taken from Native Americans available to settlers for free if they were willing to live on it for five years and make improvements. Promotional brochures published by the large transcontinental railroads hastened settlement. By the late 1800s, new settlers—the Cranston family among them—began to pour into Montana.[28]

Benjamin’s eldest son Edward, born in September 1864, a month before his grandfather Edward died, was the first in the family to go to Montana, leaving Ohio in 1885, when he was 20 or 21.[29] David, born in 1870, was there by 1890; David’s twin Jake and younger brother George, born in 1873, arrived in the early summer of 1895.[30] Ruth, their older half-sister, left for Montana in the spring of 1896, intending to keep house for her brothers, but apparently she got no further than Indiana, where she was married on 19 June 1897. By 1910 she had left her husband and was living with her brothers in Great Falls.[31] Sisters Annie and Abbie and brother John were in Great Falls by 1900, when they lived with Jerry, Jake, George, and David in a rented house at 1700 Fifth Ave. North.[32] Sisters Amelia and Alice and brother William, the youngest, were still in Wheelersburg with their widowed mother in 1900,[33] but by 1903, all four were in the house at 1700 Fifth Ave. North.[34]

History Museum of Hood River County (historichoodriver.com), courtesy of the Episcopal Diocese of Eastern Oregon.

The Homestead Act allowed any twenty-one-year-old head of a household, male or female, to homestead federal land. Between 1904 and 1913, ten of the Cranston siblings and their mother claimed and “proved up” title to more than 1,700 acres of land in Cascade County. Several of the parcels were contiguous.[35] It was the same method their grandfather has used, under an earlier enactment of the homestead law, to obtain title to land in Ohio.

The brothers took jobs to support the family while the homesteads were being “proved up.” Edward and George worked for the Great Falls Street Railway Co., and Jerry, Jake, John, and David worked at the “B&M,” the huge copper smelter in Great Falls operated by the Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company. David, who worked there the longest, rose to the rank of foreman.[36]

Edward must have gotten into the cattle business at the turn of the century; he registered his first cattle brand in 1902. In 1910, he received the deed to the homestead he claimed near Milligan. David and Jake later registered their own cattle brands. The brothers formed a partnership called Cranston Brothers to raise stock. By the 1920s, the business had registered a Cranston Brothers cattle brand and was buying Hereford cattle at auction.[37]

Life on a rural homestead was difficult. One homesteader’s wife described it this way: “You’d go to bed about eleven-thirty, twelve o’clock, you’d get up at four, and you go out and help harness the horses, you milked the cows, get breakfast, strain your milk and put it away. Wash up your dishes, feed your chickens and slop the pigs. If there was any time left, you would start your washing, maybe carry your water … heat your water in a boiler, get your washboard and your tub…. Wasn’t many times I’d fool around.” Many men married simply to divide the labor. “There were darn few marriages of love out here among these early beginners . . . A man just couldn’t work out in the field all day and then come in and start the beans boiling—it didn’t work. You realize that washing clothes was almost a two-day operation in the wintertime . . . Just running the household was a full-time job, so you went out looking for a woman and you went out fast . . . I don’t think I’ve ever heard a homestead wife tell how much she loved her husband. That wasn’t part of it, it was survival.”[38]

The Cranston brothers had their sisters to run their households, which may have been one reason why Jake was the only one who married. But the family endured other difficulties. In February 1903, Amelia gave birth to an out-of-wedlock son in Great Falls. Three days later, she married the baby’s father, Edward Price, in a Presbyterian ceremony in Piketon, Pike Co., Ohio. It is not known whether or for how long they lived together before they divorced. She remarried six years later and settled on her homestead at Castner Falls. Her sisters and brothers raised her son Waldo, who was adopted by his uncle William. Amelia and her second husband, Thomas D. Norman, had two children. The younger one, a son, was nine years old in 1926 when he drowned in the Missouri River.[39]

In November of 1903, Jerry was hauling logs from the mountains to his ranch on Hound Creek when the load broke loose and the logs rolled over him, knocking him to the ground and breaking his neck. His brother John and another man found the body. He was 37.[40] John was committed to St. Bernard’s Sanatorium for the Insane in Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1910, dying there in 1916.[41] George, who was seriously injured in a railway car accident in 1900, died in 1911 at the age of 37.[42]

Ruth, who never remarried, ran her homestead alone. Annie married in December 1911 but was divorced only five months later.[43] Alice and her husband, a German immigrant, ran a stock ranch near Milligan.[44] Jake, a dairy farmer, married twice—both wives were natives of Scioto County—but left no children.[45] Edward, Dave, Abbie, and William never married. Abbie lived with her brother William and sister Annie on William’s homestead near Castner Falls.

Edward, Annie, Abbie, Alice, Dave, John, and William are buried in the Cranston plot at Highland Cemetery in Great Falls. Edward’s earliest two cattle brands are carved in the bottom corners of the Cranston monument.[46]

Cranston monument at Highland Cemetery, Great Falls, with cattle brands.

FindAGrave.com memorial # 53921386.

[Banner image: The Cranston Woolen Mill in Wheelersburg, Ohio. The date is uncertain, but it could be about 1845, when Edward Cranston still owned the mill.]

Notes:

[1] Kurt B. Mayer, Economic Development and Population Growth in Rhode Island (Providence, R.I.: Brown University, 1953), 24-26. [2] Percy Wells Bidwell, “Rural Economy in New England at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century” (Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 20(1916):385-390.) [3] Lois Kimball Mathews, The Expansion of New England (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1909), 174. [4] No record of Edward’s birth date can be located. His burial record (at FindAGrave.com memorial # 63860463) says he was 73 years, 8 months, and 24 days old when he died on 26 October 1864, but that would put his date of birth at 2 February 1791, only five months after the birth of his older brother Samuel. It is more likely he was born 2 February 1792. [5] Eugene B. Willard, ed., A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio, 2 vols. [hereafter Willard, Hanging Rock] (Chicago, Ill.: Lewis Publishing Co., 1916), 2:884. [6] Nelson W. Evans, A History of Scioto County, Ohio [hereafter Evans, Scioto County] (Portsmouth, Ohio, printed for the author, 1903), 1:76. [7] Henry T. Bannon, Scioto Sketches: An Account of Discovery and Settlement of Scioto County, Ohio [hereafter Bannon, Scioto Sketches], (Chicago, Ill.: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1920), 31, 46, 51. [8] Bannon, Scioto Sketches, 53. [9] Portsmouth Times (Portsmouth, Ohio), 24 December 1870, p. 1. [10] Evans, Scioto County, 76, 705. [11] Scioto County Deeds, E:244 (recorded 29 March 1820); Evans, Scioto County, 439-440. [12] Evans, Scioto County, 76, 629. [13] William Jones, “Cranston: More Additions and Corrections,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 87(1933):79. [14] Portsmouth Gazette and Lawrence Advertiser (Portsmouth, Ohio), 14 January 1825, p. 3. [15] History of the Lower Scioto Valley, Ohio [hereafter Lower Scioto Valley] (Chicago, Ill.: Inter-State Publishing Co., 1884), 316. Rev. Dan Young would later serve two terms in the Ohio legislature. Portsmouth Daily Times (Portsmouth, Ohio), 12 July 1897, p. 4. [16] Willard, Hanging Rock, 2:884-886. [17] Ibid. [18] 1850 U.S. Census, Porter Township, Scioto Co., Ohio, agriculture schedule, roll 9, line 23. [19] 1850 U.S. Census, District 133, Scioto Co., Ohio, industry schedule, roll 13, line: 3. [20] Evans, Scioto County, 37, 49, 77. [21] Canton Repository (Canton, Ohio), 3 January 1846, p. 3; Evans, Scioto County, 1:277. [22] Jones, “More Additions,” NEHG Register, 87(1933):78. [23] Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), 12 February 1918, p. 6. [24] Lower Scioto Valley, 323; Portsmouth Daily Times, 8 June 1897, p. 1. [25] Portsmouth Times, 11 October 1862, p. 3. [26] Tom Stout, Montana: Its Story and Biography (Chicago, Ill.: The American Historical Society, 1921), 681, 686-7. [27] Portsmouth Times, 21 November 1903, p. 1. [28] Derek Strahn, Distinctly Montana (Star Ridge New Media, LLC) (http://www.distinctlymontana.com). [29] Portsmouth Times, 18 April 1885, p. 3. [30] Portsmouth Daily Time, 24 December 1894, page 1; 5 June 1895, p. 1; 8 September 1898, p. 1; Portsmouth Times, 11 May 1895, p. 6. [31] Portsmouth Daily Times, 25 April 1896, p. 1; Portsmouth Times, 26 June 1897, p. 2; 1910 U.S. Census, Great Falls, Cascade Co., Montana, roll 830, p. 11B. [32] 1900 U.S. Census, Great Falls, Cascade Co., Montana, E.D. 148, p. 33. [33] She was the former Francis (sic) Jane Elick. Benjamin married Margaret Henderson in 1855 but she died in 1860, leaving two daughters, Kate—the only sibling who did not move to Montana—and Ruth. Benjamin and Francis married in November 1861. (Lower Scioto Valley, 323.) Benjamin died in Wheelersburg in 1894. [34] 1900 U.S. Census, Porter, Scioto Co., Ohio, E.D. 115, p. 1; R.L. Polk & Co. and W.T. Ridgely’s Great Falls and Cascade County Directory, 1903, 124-125. [35] U.S. Dept. of Interior, Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records database (https://glorecords.blm.gov/). [36] 1900 U.S. Census, Great Falls, Cascade Co., Montana, E.D. 148, p. 33; R.L. Polk & Co. and W.T. Ridgely’s Great Falls and Cascade County Directory, 1903, p. 124-125; 1904, p. 120; 1906, p. 94-95; 1908, p. 102; 1910, p. 101; 1911, p. 117. [37] Great Falls Tribune (Great Falls, Montana), 31 May 1922, p. 14. [38] “The Work Was Never Done: Farm and Ranch Wives and Mothers” Women’s History Matters, Montana Historical Society (http://montanawomenshistory.org). [39] Cascade County Vital Records, Births, B:94; “U.S. Presbyterian Church Records, 1701-1970,” Ancestry.com database; “Cascade County Records, 1880-2009,” FamilySearch.org database; Jean Conrad Rowe, Mountains and Meadows: A History of Cascade County [hereafter Rowe, Mountains and Meadows] (Great Falls, Mont.: Blue Print & Letter Co., 1970), 227. [40] The Butte Inter Mountain (Butte, Montana), 6 November 1903, p. 1. [41] 1910 U.S. Census, Council Bluffs, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa, roll 421, p. 4A; Great Falls Tribune, 9 October 1916. [42] Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), 26 October 1900, p. 11; FindAGrave.com memorial # 64506220. [43] “Montana, County Marriages, 1865-1950,” FamilySearch.org database; Helena Independent Record (Helena, Montana), 5 May 1912, p. 4. [44] “Montana, County Marriages, 1865-1987,” Ancestry.com database; Great Falls Daily Tribune, 4 October 1919, p. 12 and 21 November 1922, p. 9. [45] FindAGrave.com memorial # 34385803; “Montana, County Marriage Records, 1865-1993,” Ancestry.com database; FindAGrave.com memorial # 91671651; “Ohio, County Marriages 1789-2003,” FamilySearch.org database; Rowe, Mountains and Meadows, 157. [46] FindAGrave.com memorial # 53921386.