With every election year there is talk of election fraud.[1] The 2020 elections are no different except that this year’s elections will be held in the midst of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic and for the first-time mail balloting will be used extensively. Should we be concerned? Of course, we should be concerned, but most likely election fraud will be inconsequential as election officials have adopted safeguards and will be on the look-out for irregular activity. Compared to many of Rhode Island’s elections of the past, when many methods were used to influence an election’s outcome, this year’s election should be uneventful – at least it is to be hoped. Regardless, it may be entertaining for the reader to take a look back at some attempts at election fraud in the Ocean State.

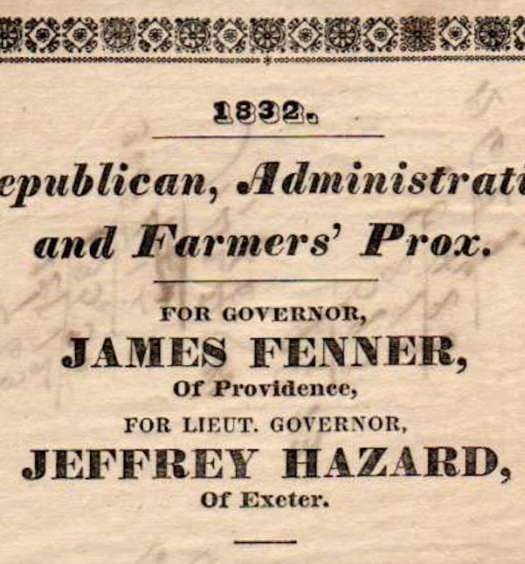

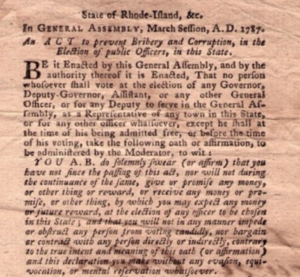

In the early years of the colony voting was done by voice vote at a single in-person meeting, but in 1664 the General Assembly passed a law allowing for voting by proxy. No longer would the voter have to appear at the annual election in Newport, the colony’s capital. Rather, he could vote at a town meeting and have his vote recorded by the town clerk and sent to Newport to be tallied on election day. This procedure did leave room for fraud to enter into the election process. By the 1740s Rhode Island voters were using paper ballots to vote for state-wide officers. There must have been concern with fraud in balloting for in 1747 the General Assembly enacted a law requiring the voter to take an oath against bribery and corruption in selection of general and town officers.[2]

Election fraud was then practiced in a number of different ways. Bribery was a relatively common practice. Money was used to corrupt election officials so that they would alter an election’s outcome. Money was also spent buying votes directly; for a few dollars some voters were willing to sell their vote. When money did not work there was always attempts at intimidation. Failing in that, there was resort to downright trickery. A full accounting of election fraud is beyond the scope of this essay. However, some examples described below are indicative of the practices used to defraud the citizens of Rhode Island of a fair election.

Bribery

Money was regularly used to sway an election. Buying votes was a normal practice, as was the use of cash payments to buy-off election officials. Tracy Campbell, in his book Deliver the Vote: A History of Election Fraud, an American Political Tradition—1742-2004, noted that by the mid-1700s, “The purchasing of votes was so popular in Rhode Island that the practice became known as “Rhode Islandism.”

Money was even used to pay people not to vote, if it was thought the voter was going to vote for an opponent. Campbell continued, “Rev. Ezra Stiles (the future president of Yale) claimed that one third of the electorate in Newport, Rhode Island, stayed away from the polls, ‘silenced by connections.’”

More than a century later, in 1866, Joseph Blake, in a speech on political corruption given to the General Assembly, stated, “Two years ago there was to be a Senatorial election, and to say nothing of other places, it was alleged and proved that the whole delegation from the city of Providence, its twelve representatives to the Assembly … were sent here by fraudulent votes, and votes bought and sold. An investigation was had and a report made, and it did appear that here, in this favored city of New England, the chief city of the state of Rhode Island, the whole set of representatives were elected by the aid of money, freely and lavishly spent in the purchase of votes.”[3]

In 1787 it was necessary for the state to re-enact a law to prevent bribery and corruption in state elections. (Author’s collection)

Numerous newspaper accounts can be found during practically every election cycle alleging some resort to bribery. Election fraud was endemic in Rhode Island; examples abound in both the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Providence Evening Press for April 3, 1884, under an article titled “Political Corruption,” stated, “In Cranston, Charles Bennett, a democrat, was detected in the act of purchasing votes, it is alleged.” According to the newspaper, Bennet “was arrested, and held in the sum of $300 bail to await trial.”

A headline in the Evening Telegram for November 4, 1904 blurted out in large letters, “Big Bribes Offered Gov. Garvin Says.” The article went on to explain, “Tens of Thousands of Dollars Promised Election Officials to Cheat Voters of the State, he declares – positions or thousands of dollars offered by men who claim and men who seem to be agents of the senior senator. . . .”

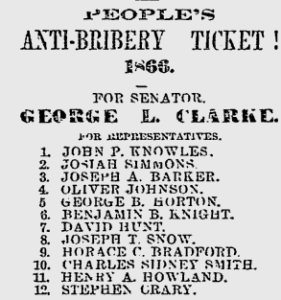

Bribery was so pervasive that in the election of 1866 there was even an anti-bribery slate of candidates for state senator and representatives. This may have been a reaction to the outcome of Joseph Black’s speech to the General Assembly of the same year. The Providence Evening Press noted that, “It cannot be called a strictly party ticket, for Democrats and Republicans have their fair share of representation.” Called the People’s Anti-Bribery ticket it ran candidates that were opponents of “the clique.” However it failed to place any of its candidates into office.

The anti-bribery ticket for Providence senator and representatives appeared in the Providence Evening Press on April 4, 1866, just before the election. It failed to place any of the listed candidates into office (Author’s Collection)

Money was involved in all elections. To get the proper perspective on the role of money in elections, the Pawtuxet Valley Gleaner ran an article in its November 26, 1885 issue under the title “Our December Election.” The newspaper wrote:

Our annual state election, it will be remembered, occurs the latter part of next month. This is not according to statue [statutory] law, to be sure, as the law provides that the election shall be held the first Wednesday of April of each year. For several years past, however, it has been fully decided who shall be the next governor before the 1st of January each year, and the election in April has been merely a ratification of the December arrangement. The December election is in the nature of an auction sale. That is, the governorship is awarded to that member of the dominant party who has the greatest desire for it, and is the most liberal in his donations to the campaign fund. The method of procedure is about as follows: The auctioneers ascertain about the number of men registered throughout the state, and are able to estimate pretty closely the number who will not pay their own registry taxes. The amount must be footed by the man desiring to become governor, together with such additional sum as the auctioneers shall assess, for commissions and any campaign contingencies that may arise. The candidate for lieutenant governor, is also obliged to pay for his whistle, but he who stands at the head of the ticket has to bear the lion’s share of the expenses. Hence it follows that no poor man can become governor of Rhode Island at the present time.

By the end of the 19th century Rhode Island was notorious for its political corruption. At that time Charles “Boss” Brayton ran the Republican Party, as well as the state from his office in the State House. Nothing happened without his approval. It was he who doled out money to buy votes and corrupt election officials. In 1905 McClure Magazine ran an article by the famous muckraker Lincoln Steffens titled, “Rhode Island a State for Sale.”[4] The same month, a pamphlet was printed titled “Vote Buying in Rhode Island as Shown by the Providence Journal.” This pamphlet was taken from a speech delivered by Col. Patrick H. Quinn, a progressive Democrat, before the Young Men’s Democratic Club of Providence in February 1905. In it, Quinn noted “There are men in the General Assembly today who would be in jail if the statute against bribery was enforced.”

While money was used to buy votes, exactly how much was paid per vote varied. Often $1 per vote was sufficient but over time the amount increased. By the late 19th century the amount could by considerable. In the 1884 election for U.S. Representative for the 2nd congressional district, Republican William Pirce defeated his Democratic opponent Charles Page by only sixteen votes. Page contested the results, which lead to an investigation in the U.S. House of Representatives.[5] During this investigation, Charles Gardiner of Warwick testified under oath that he received two dollars for his vote. Another witness, Alfred Johnson, also of Warwick, said he received three dollars.[6] Numerous others testified, all claiming payment for their votes from two to three dollars.

During the House’s investigation, some defenders of vote buying said they considered it as compensation for the voter’s lost time and did not constitute bribery. U.S. Representative Henry G. Turner from Georgia did not agree, quipping sarcastically, “the time might come when a man in New England would have to be paid to celebrate the Fourth of July.”

Four years after the soiled election of 1884, another instance arose when the general election in Warwick caused votes to be bought for as much as $15 in order to get the town’s Republican candidate for lieutenant governor into office. One newspaper account noted, “the buying and selling of votes was particularly open and talked about without shame.”[7]

In an interview between former Rhode Island governor Robert Quinn and then college professor Matthew Smith, Quinn stated that during the 1920s vote buying was common and often done in the open. The usual price for a vote was $2, but Quinn explained that in one election the price per vote was as much as $20 in West Greenwich.[8] While this was a large sum it should be remembered that West Greenwich was sparsely populated. Therefore, it would cost less to buy a state senate seat there than in the larger towns and cities where there were many more voters to bribe. After all, at the time, a state senator’s vote from a small town carried as much influence in the state senate as did a state senator’s vote from a large town. Perhaps $20 per vote was a bargain.

Intimidation

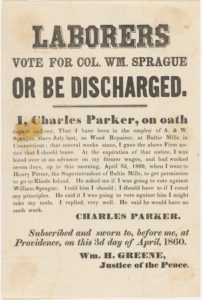

When bribery failed to accomplish the desired goal, another method in slanting an election’s outcome was through the use of intimidation. Often this manifested itself in the way of lost employment. This was especially true for workers in factories who were often directed whom to vote for by their supervisors. A good example of such an instance occurred in 1860 when Charles Parker, working in the Baltic Mills in nearby Connecticut, wanted time off to return to Rhode Island to vote. When asked by the mill’s superintendent if he intended to vote against William Sprague, Parker replied he would. Unfortunately for Parker, the Baltic Mill was owned by William Sprague and as such the superintendent informed Parker his services were no longer needed. The day before the April 4, 1860 election a broadside appeared telling of Parker’s experience and discharge. Whatever the impact of the broadside was intended to have, it failed as Sprague was elected governor, the first of his three consecutive one-year terms as Rhode Island’s chief executive, including through the Civil War.

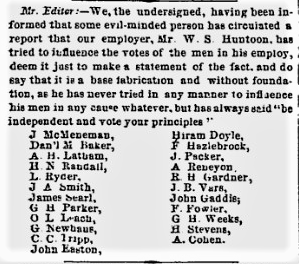

An interesting twist on this was given just one day after the claim made by Charles Parker. Some 23 employees of W.S. Huntoon, a Providence cigar manufacturer, felt inclined to inform the press that they were not being pressured, as was allegedly claimed, into voting as their employer directed but rather were told by him to be “independent and vote your principles.” The question remains why such a letter was needed at all and whether the letter was offered freely or there was pressure to sign it.

This broadside was issued with the intent to influence voters in the April 1860 election. Presumably paid for by Sprague’s opponent (Image courtesy of Brown University Library)

Job security was often used as a lever on workers in the larger cities who owed their jobs to political patronage. These workers were often expected to perform a variety of duties in support of the sitting candidate. These duties could be as simple a buying a block of tickets to the incumbent’s fund-raising dinner, working on election tasks (often while still on the clock for the city), and, of course, voting as directed by the employee’s supervisor. In a small pamphlet published in 1880, following a U.S. Senate investigation, it was noted that the New England Granite Works and the Smith Granite Company, both of Westerly, issued a joint circular addressed to their voting-age employees, stressing that the election of Mr. Tilden would be a great injury to their business and that it was in their employees’ best interest to vote against Mr. Tilden.

In the same pamphlet one witness testified, “I have known men employed in the Woonsocket machine shop to be marched up, in a hall, in squads by a man named Chase …. compelled to hold their hands up with the ballots in them in this manner. [The witness elevated his right hand to a level with his head.] They walked along and he went to them, watching them until, as each man dropped the ballot in, he took his eye off the men.”[9]

A letter to the editor of the Providence Daily Post for April 4, 1860 stated employees were note instructed by the employer on which candidate to vote for (Author’s Collection)

A good 20th century example of being dismissed for not voting as directed can be found in Providence during the 1939 election that pitted William Vanderbilt, a Republican, against Democrat incumbent Robert Quinn. Stefano Luconi, in his book, The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island 1916 – 1948, recounts how Frank Petracrca was dismissed from his job by his foreman, Lucca Masciarelli. Petracrca had exclaimed, “I voted as I saw fit and not as Mr. Masciarelli wanted.”[10]

Stuffing the Ballot Box

Until the advent of the Australian ballot system in 1889, Rhode Island voters cast paper ballots for state-wide office. These ballots were supplied not by the state but by the candidate or his party. How many ballots got printed was up to the party and there was no strict accountability for their distribution. Normally party operatives were at the polling places ready to distribute ballots to the voter. In almost all elections of the 19th century there was some instance of ballot stuffing. After the introduction of the Australian ballot system, local elections continued to use paper ballots and as expected ballot stuffing continued.

Sometimes people were hired to vote, and not just one time, but multiple times in an election. Such conduct added new meaning to the phrase, “vote and vote often.”

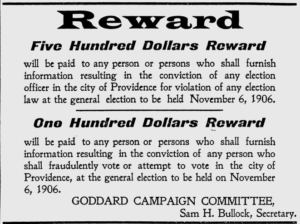

This three column political ad in the Providence News Democrat on November 3, 1906 offered a monetary reward for reports of election fraud in Providence (Author’s Collection)

Stories have been told of people changing their clothing or wearing disguises to vote more than once in an election. Historian Debra Mulligan noted in her article on illegal wiretapping in Pawtucket that in 1938 “in District 3, Ward 6, a handy garage located across the street from the polls, served as a fitting room for floaters who hurriedly changed their outer garments and rushed to the side door with their bogus “identification cards,” where policemen “in the know” ushered them in to place their multiple ballots, in some cases up to twenty, for McCoy and his lieutenants.”[11]

Occasionally these hired “floaters” would vote in different wards to escape detection. Nothing was considered unethical by some party operatives in order to get their candidate into office.

Even the dead voted – or at least votes were cast in the names of the recently departed. Examples of such activity appeared in the local newspapers. For example, the Pawtuxet Evening Times reported on June 10, 1891 that the election in the town of Lincoln was put in question when 110 tissue ballots were stuffed into the ballot box in favor of the Democratic candidates. Presumably, it was easier to fold tissue paper ballots than regular paper ballots in order to stuff them into the ballot box without detection. The ballots in this instance were retrieved and not counted. In a small town like Lincoln, 110 ballots could easily sway an election’s outcome.

Election fraud was considered rampant enough in 1906 for the Democratic committee of Robert H.I. Goddard’s campaign for United States Senator to offer a reward for reporting fraudulent voting and other election violations. Goddard, a Democrat and the self-professed people’s candidate, was running against Samuel P. Colt, the Republican candidate. Colt was also said to be the pick of the Aldrich – Perry – Brayton combine.

Ballot stuffing not only occurred in state and municipal elections, but it also plagued balloting for members of the General Assembly. In January 1923, the Grand Committee of the General Assembly met to elect judges and sheriffs but in a late night session, while voting for judges in the Eleventh and Twelfth District Courts, the first two rounds of balloting were declared invalid when it was discovered that there were more votes casts then there were members of the Grand Committee.

Voting fraud is no laughing matter, but one little snippet that appeared in the May 16, 1832 issue of the Republican Herald can still generate a chuckle and is worth repeating here:

“Look at your lying Herald,” said our pleasantly laughing friend Oliver, the other day, to a republican neighbor.

“But the Herald always speaks the truth, friend Oliver.”

“No, but it don’t though. Didn’t they say, not long since, that I put fourteen names, by way of proxy, at the ward meeting? It was a lie! I only put in TWELVE. Ha, Ha, Ha!!!”

Duping the Voter

One way to rig an election was to trick the voter into thinking he was voting for one candidate when in reality he was voting for another. The Newport Daily News warned voters of just such a ploy on April 1, 1857 (an appropriate date to say the least) when it ran an article titled, “Look out for Spurious Tickets.” The article stated, “All descriptions of mongrel tickets will be circulated today, and every voter should examine his vote before he places it in the box. Men who would shrink from robbing another of money will seek to defraud him of his vote, by substituting one similar in appearance but with some name changed! Which is worse.”

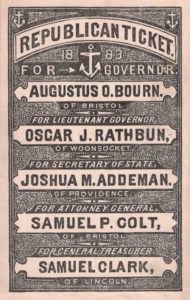

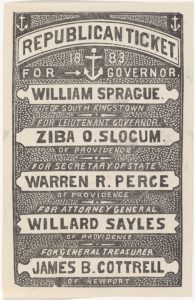

The best example of such a tactic occurred in 1883. Augustus Bourn ran for governor on a Republican ticket. The ticket, often referred to as the patent medicine ticket, was most elaborately designed – quite unusual for a Rhode Island ticket. Bourn’s opponent was former governor William Sprague who was running as a Democrat. Some unscrupulous Democratic operative had tickets printed to look exactly like the Republican ticket, even calling it a Republican ticket. The only difference was all the candidates on the ticket were Democrats. It is uncertain how many voters were duped by this chicanery but in the end all of the candidates on the real Republican ticket were elected to office.

Shortly after the 1883 ballot deception, another instance occurred of an altered ballot. This time is was the Republicans trying to pull a fast one on the Democratic voters of Warwick. In 1888 Enos Lapham was running for lieutenant governor as a Republican. Republican operatives had Democratic ballots printed with the names of the all the legitimate Democratic candidates on the ballot except for lieutenant governor. On these ballots Lapham’s name appeared in place of Howard Smith who was the real Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor. Lapham was elected to office.

At first glance both tickets shown here appear the same; but the below ticket is claiming to be a Republican ticket was in fact a ticket containing all Democratic candidates. (Above ticket is from author’s collection, below ticket is courtesy of Brown University Library)

In more recent times former Providence Mayor Vincent “Buddy” Cianci recounted in his book Politics and Pasta how South Providence political operative Lloyd Griffin went to the residences of the elderly, shut-ins and retirement homes to persuade these voters to have their mail ballots sent directly to Griffin’s headquarters. “When the ballots arrived, he might have taken them to the people who requested them. It’s possible. I was told that his people were so nice they would actually help people fill out their ballots. And if, for example, they didn’t want to vote for Mayor Cianci, they would happily put an ‘X’ right next to his name.” Cianci went on to say, “Lloyd had a bit of trouble differentiating between an absentee voter and a fictitious one.”[12]

The Greatest of All Election Frauds

Some of the most egregious election frauds took place in the 20th century. In 1915 there were 37 individuals arrested in Coventry and North Providence for election fraud during the previous year’s congressional election. One of those arrested was the state senator from Coventry. This fraud led to a federal grand jury investigation and eventually a case was heard before the United States Supreme Court to determine the extent of the federal government’s powers to prosecute for fraud in state elections.

The 1915 episode in Rhode Island election misdeeds pales in comparison to the number of people indicted for fraud in Pawtucket in the election of 1938. If the returns for this election are credible, 97.2% of all eligible voters went to the polls. Following a Providence County Grand Jury investigation, 169 people were indicted, including a probate judge, the Pawtucket Commissioner of Public Works, the City Engineer, the Superintendent of Parks, the Director of Public Aid, 16 policemen and 95 city employees.

The investigation into this Pawtucket fraud also became a cause célèb in and of itself when it became known that Governor Vanderbilt funded at his own expense a New York detective agency to investigate the matter and this investigation included illegal wiretapping of both Mayor Thomas McCoy’s office and home, as well as the phone line of State Attorney General Louis Jackvony.[13]

A Stolen Election?

The quote “Those who vote decide nothing, those who count the vote decide everything” is attributed to Soviet Union dictator Joseph Stalin. The sentiment also has a direct application to Rhode Island.

In the second half of the 20th century, the 1956 gubernatorial election stands out for its curious outcome. That year, incumbent Democratic governor Dennis Roberts faced off against Republican Christopher Del Sesto. When the votes were counted Del Sesto was the apparent winner by 477 votes. The Roberts campaign, however, requested a recount. The decision was finally resolved by the Rhode Island Supreme Court in what is known as the “long count.” The court threw out nearly 5,000 absentee and shut-in ballots on the technicality that these ballots were cast before election day and not on election day as required by the State’s constitution. Roberts was ultimately declared the winner by 711 votes. What makes this election “smell funny” was that Roberts’ brother, Thomas Roberts, sat on the Supreme Court, although he did recuse himself.[14]

The Rhode Island Supreme Court invalidated 4,954 absentee ballots in 1956. Two years later the Republican handbill depicted here was used to remind voters of the perceived election fix (Author’s Collection)

Was there fraud in the 1956 election? It depends on who you ask; many believed there was. Two years later the voters had their say when Roberts again faced-off against Del Sesto. This time Del Sesto won by a margin of 6,230 votes. Roberts would never again hold public office.

Conclusion

Election fraud in Rhode Island has been around since it was a colony of Great Britain. It would be near impossible to account for all the fraud perpetrated in state elections. Human nature being what it is, there will always be someone or some political campaign trying to get an unfair advantage over an opponent. Despite all attempts at election fraud, by and large the candidate who received the greatest number of votes, fairly earned or not, served in office. Regardless, today citizens and election board officials will need to be ever vigilant. With regard to this year’s pandemic driven mail-in ballot experiment only time will tell if another paragraph will have to be added to this essay.

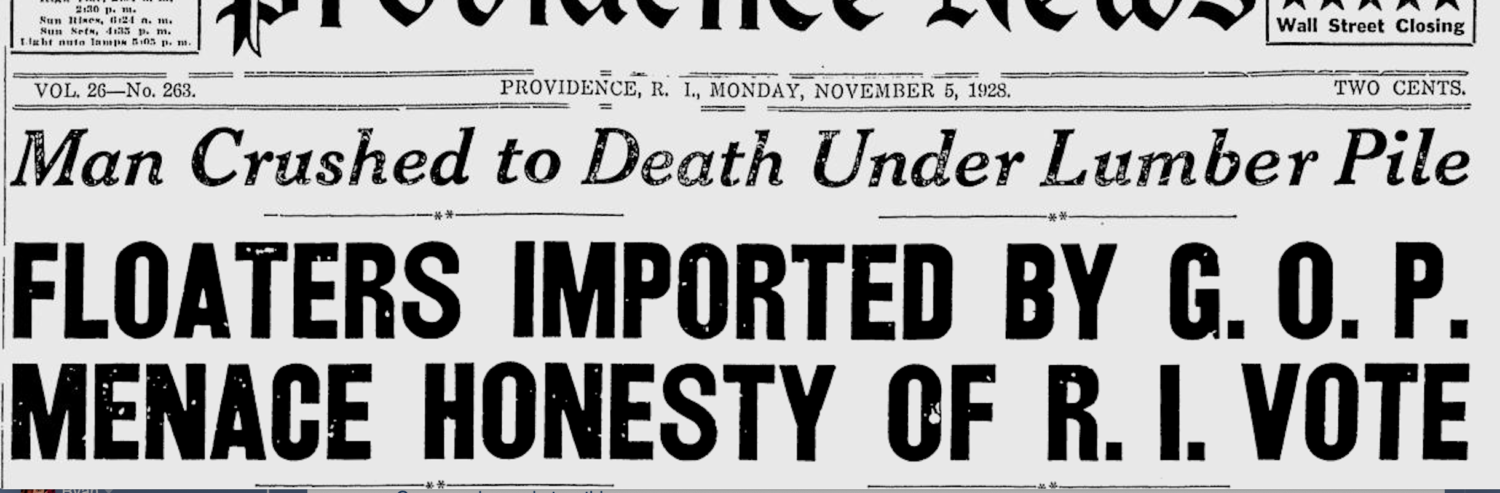

Banner image: Providence News, November 5, 1928.

Bibliography

Blair, Henry, Suffrage in Rhode Island – In Senate of the United States. [1880].

Bartlett, John Russell, ed., Rhode Island Colonial Records, 10 Volumes (Providence, RI: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1856-1865).

Blake, Joseph M., Political Corruption in Rhode Island (Providence. RI: Providence Free Press, 1866).

Boucher, Susan M., The History of Pawtucket 1635 – 1976 (Pawtucket, RI: The Pawtucket Public Library, 1976).

Campbell, Tracy, Deliver the Vote – A History of Election Fraud, An American Political Tradition 1742 – 2004 (New York, NY: Carroll and Graf, 2005).

Cianci, Vincent “Buddy” Jr., Politics and Pasta (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2011).

DeSimone Russell J., ed., “Fighting Bob” Quinn – Political Reformer and the People’s Advocate (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2020.

Lowry, E., “To the People of Rhode Island – A Disclosure of Political Conditions and An Appeal for Their Reform,” reprinted from the New York Evening Post, 1903.

Luconi, Stefano, The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island 1916 -1948 (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004).

Massachusetts and Rhode Island – Discrimination Against Foreign-Born Citizens, Compulsory Voting With Employers (Washington, D.C., The Globe Printing Office [1880]).

Mulligan, Debra A., Democratic Repairman – The Political Life of J. Howard McGrath (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2019).

Mulligan, Debra A., “Political Rivalry in Rhode Island: William H. Vanderbilt vs. J. Howard McGrath: The Wiretapping Case,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 35 (Winter 2007), 52–77.

Quinn, Patrick H., Vote Buying in Rhode Island (1905).

Steffens, Lincoln, “Rhode Island: A State for Sale,” McClure’s Magazine 24 (February 1905), 337-339.

Notes:

[1] This subtitle is taken from an article in the Providence Evening Press, April 3, 1884. [2] See Bartlett, Rhode Island Colonial Records, Volume II, page 62. [3] See Blake, Political Corruption in Rhode Island, pages 6-7. [4] Lincoln Steffen’s article “Rhode Island: A State For Sale” was reprinted in the Online Review of Rhode Island History in April 2017, see: http://smallstatebighistory.com/rhode-island-state-sale/. [5] Following an investigation in the U.S. House of Representatives, the seat was declared vacant on January 25, 1887. A special election was held three weeks later on February 11, 1887 in which Page defeated Pirce with a plurality of 295 votes. [6] Pawtuxet Valley Gleaner, February 19, 1887. [7] Providence Journal, April 9, 1888. [8] See DeSimone, “Fighting Bob” Quinn – Political Reformer and the People’s Advocate, page 125. [9] See Massachusetts and Rhode Island – Discrimination Against Foreign-Born Citizens. Compulsory Voting With Employers., page 7. [10] See Luconi, The Italian-American Vote in Providence, Rhode Island 1916 – 1948, page 98. [11] See Mulligan, “Political Rivalry in Rhode Island: William H. Vanderbilt vs. J. Howard McGrath: The Wiretapping Case,” page 17. [12] See Vincent “Buddy” Cianci Jr., Politics and Pasta, pages 138 and 150. In March 1977 a special election to fill a vacancy on the Providence City Council in that city’s tenth ward resulted in the case of Griffin v. Burns before the United States Court of Appeals for the First District.. Griffin was one of five candidates. While Griffin received 30.5% of the machine ballots he received 85.5% of all absentee ballots and 94.4% of all shut-in ballots. As head of the Providence Revitalization Committee many of these votes may have come from Griffin’s tenants. The issue of the lawsuit was whether absentee and shut-in ballots were valid in a primary election. The RI Supreme Court ruled them invalid but the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled otherwise. [13] See Mulligan, “Political Rivalry in Rhode Island: William H. Vanderbilt vs. J. Howard McGrath: The Wiretapping Case,” pages 52 -77. [14] Providence Journal, December 23, 1956