[This article appears as a chapter in the newly-released book by three smallstatebighistory authors, titled Untold Stories from World War II Rhode Island (History Press, 2019)]

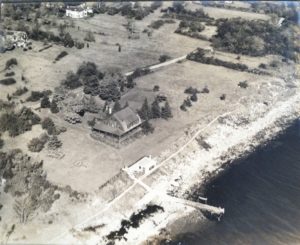

Elisabeth Kellog Sheldon knew she was fortunate. Known as Betty, she enjoyed her privileged upbringing that included attending private boarding schools and a private college. Now here she was in early June 1944, a pretty and bright twenty-year-old woman ready to spend another summer in her family’s twelve-bedroom shingled house north of Saunderstown called Spindrift, with its commanding view of gorgeous Narragansett Bay. And she could continue sailing with the nearby Saunderstown Yacht Club and visiting her friends at the exclusive Dunes Club in Narragansett.

There was a lot to see in Narragansett Bay, at the height of World War II. To the north stood the Naval Air Station at Quonset Point, the largest Navy air base in the Northeast. Aircraft coming and going from Quonset Point roared over Spindrift incessantly. Across the bay in Newport, at Goat Island, most of the Navy’s torpedoes for submarines, destroyers and PT boats were being built, one at a time. In the bay, some of these torpedoes were tested, fired out of the end of a modified building at the tip of Gould Island, and then tracked and recovered by small boats scurrying after them. In Portsmouth, a PT boat training center had arisen almost overnight, and the small PT boats traveling in packs could be heard barreling up and down the bay. And, of course, there was a constant stream of Navy warships coming in and out of the bay—mostly destroyers and destroyer escorts, but on occasion, larger ships, such as heavy cruisers or a flat-top aircraft carrier.

It was unusual that Betty and her family were allowed to remain in Spindrift that summer and the previous two summers. Most of the summer homes on the bay had been requisitioned for the use of Navy officers stationed at Quonset Point. Betty was thus lucky that her family did not have to leave Spindrift. Well, not really lucky. Her parents had recently separated, and since this was the only house her mother, Margaret Chase Sheldon (called Marjorie), had, the family was allowed to remain. For most of the year, Betty attended college at Bryn Mawr outside Philadelphia, while her younger sister attended a local private boarding school. Her two older brothers were already serving in the military, and her older sister Peggy had moved to California after marrying a Navy pilot who was then flying missions in the Pacific. Now it was the beginning of another warm and breezy summer on Narragansett Bay.

Betty spent much of the time with her spunky sister, Louise (known as Lulu), two years younger. Both were skilled sailors, taught by their energetic father, James Rhodes Sheldon, descended from an old Rhode Island family, who insisted that his young girls should learn to sail just like young boys. Active members of the Saunderstown Yacht Club, the Sheldon sisters typically sailed wooden fifteen foot Lawley’s; Betty’s father had given her one for Christmas in 1938.

The first thing Betty did each summer during the war was to obtain her sailing permit so she could sail her sailboat Sirocco in local waters. Rhode Island had been declared a “vital war zone,” which meant strict security against spies and precautions against sabotage of military bases and war industries. Certain parts of Narragansett Bay were off limits, particularly where torpedo testing occurred. When Betty obtained a permit to sail in parts of Narragansett Bay, her permit contained an ominous condition: “ENEMY ALIENS ARE PROHIBITED ON BOARD.” While sailing that summer and the next, she never saw any enemy aliens swimming in the bay.

Since gas was rationed tightly during the war, Betty and Louise often traveled most places by bicycle. Betty and a friend once cycled over to Fort Kearney at Saunderstown, to check out the new top secret facility there.

Back at Spindrift, their mother, Marjorie, did what she could for some of the military officers in the area, inviting them to dinners and social gatherings. She was very civic-minded and enjoyed providing a “home away from home” for the officers. Betty and Louise, as well as their friends, were also glad to extend hospitality and friendship to the officers in the area.

A small Coast Guard boat, YP-15, patrolled the bay near Spindrift. Louise recalled, “We became friends and we had the crew over for a swim and a meal many times.” Betty and Louise would leave a towel on a fence to alert the crew to when a cake had been baked.

Marjorie and her mother Lizzie also organized events at the nearby Dunes Club for officers at Quonset Point, who were permitted to use the club’s facilities. The officers looked sharp in their dress white uniforms when they arrived at the Dunes Club. Betty and Louise would often attend evening events at the Dunes Club, mingling and dancing with the Navy pilots. The pilots hailed from all parts of the country. They missed their families and friends, and welcomed the brief distraction the Sheldon sisters and their friends at the club provided.

The Naval Air Station up the road at Quonset Point had two primary missions. First, it sent out airplanes daily to search for and destroy German submarines prowling in offshore waters that tried to sink any American merchant ships they could find. Second, Quonset Point trained torpedo, bomber, and fighter pilots, mostly to be sent to war in the Pacific against the Japanese. Some of them were taught to fly off aircraft carriers and to fight in nighttime conditions, often down the road at the Navy air field at Charlestown.

“Several of the fighter pilots we knew thought it was daring to fly under the Jamestown Bridge and a couple did,” recalled Louise. “Flying under the bridge was prohibited as extremely dangerous!” she added. Louise also recalled the excitement when a new type of plane arrived for them to fly at Quonset, especially the F6F Hellcat.

Betty had an obsession with PBMs and PBYs, huge reconnaissance aircraft known as flying boats, because they could take off and land on the bay. The word obsession was rarely used back then; she admitted she had been “wild about PBMs.” She even had a small model PBM in her bedroom. Betty loved to hear the PBMs (Martin PBM Mariner flying boats) and PBYs (PBY Catalina flying boats) roaring over her house at 7:30 in the morning, on their way to antisubmarine patrols in Block Island Sound, Long Island Sound, and the Atlantic Ocean. She knew that the planes would return and arrive back at Quonset Point later in the day at 3:30 p.m. She and Louise would sail their Lawleys up the bay to Quonset Point to watch the seaplanes when they returned and landed on the bay in the late afternoon. “The cascade of the water spray when the PBMs landed was beautiful,” Betty fondly remembered years afterward.

Betty Sheldon sailing her Lawley 15, Sirocco, in Narragansett Bay, circa 1942 (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman)

After landing, the plane’s thirteen crew members would crowd around the exit door, chatting with the sisters in their sailboats. No doubt they also took notice of the two-piece swim suits the sisters wore, made by them from used jeans, which at that time was rather exotic. Louise also recalled, “My sister and I loved to sail around the moored PBYs and talk to the crews. It was a long haul back to Saunderstown against the prevailing breeze!” Betty also recalled passing Wickford and seeing new anti-submarine warships being built at the Perkins & Vaughan shipyard there.

Photos in Betty’s scrapbook, the one of the left of her with her model PBM, the one on the right with a real PBM flying overhead, 1944 (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman)

Eventually, two PBM pilots, at a Dunes Club event, took an interest in the Sheldon sisters. One of them, twenty-three year-old Jim Bistodeau from Dayton, Minnesota, became smitten with Betty. After attending the University of Minnesota, he had enlisted in the Navy in June 1942. He was then commissioned a lieutenant at Corpus Christi, Texas, in September 1943, where he trained to fly planes. He arrived at Quonset Point that summer to train to fly PBMs and he was one of a group of officers Marjorie had invited to social gatherings at Spindrift. His experience with PBMS piqued Betty’s interest in Jim; he in turn, quickly fell madly in love with her.

Jim’s fellow pilot, Lieutenant Otho Leonard (also known as O.L.) Edwards, liked Louise. But Louise was still too young for a serious relationship. Otho had also enlisted in the Navy in 1942. The four of them also palled around with another Navy pilot, tall and handsome Forbes Whiteside. They all had fun together, spending as much time with each other as pilot training would allow.

In the early evening of September 14, 1944, a tropical hurricane struck Rhode Island. Known as the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944, it packed powerful winds. It was not as destructive as the Hurricane of 1938 that had flattened the Dunes Club and the Coast Guard House in Narragansett, and had killed so many in the state. Still, it caused considerable damage in southern New England, including at Spindrift. Jim, Otho and Forbes rushed over to the house the next morning to help the Sheldons clean up. They made it a fun day.

But the war beckoned. Jim’s, Otho’s, and Forbes’s training was coming to an end. Jim and Otho would fly in the same squadron of PBMs in the Pacific, VPN-27, and Forbes would be sent to Europe. Jim told Betty that he loved her and wanted to marry her. Betty was unsure how to respond. She was fond of Jim, of course, but she was still young and naïve, having never had a serious relationship before. But she knew that Jim would soon be far away from his family and risking his life fighting against Japan. She wanted him to be happy and have something to look forward to. She said yes to his proposal.

Betty and Jim were engaged! They talked about a ring, and in the meantime, Jim gave Bette his leather flight jacket. On September 5, Jim and Otho saw Betty off on a train at the West Kingston station, on her way to Bryn Mawr College. Soon the pilots were off to war. Betty wrote to Jim nearly every day.

Margie Dunbar, a close friend of Betty Sheldon’s, and the Narragansett town fire chief, watch the clean-up at Spindrift after the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944. Margie would learn how to yodel from Lieutenant Robert Pestalozzi of nearby Fort Kearney (Collection of Elisabeth Kellog Sheldon Aschman)

In the summer of 1945 Marjorie Sheldon invited for dinner officers at Fort Kearney, located just down the road in Saunderstown, just above the old ferry landing at the end of South Ferry Road. Fort Kearney was the location of a new and extraordinary prisoner-of-war camp for German soldiers. This top-secret camp was designed for anti-Nazi POWs who hated Hitler. The U.S. Army taught them about democracy, and they, in turn, published a newspaper that was distributed to some 380,000 German POWs in the United States, trying to persuade their fellow POWs to help build a democratic and tolerant postwar Germany. Even though the war with Germany had ended with Allied victory in May 1945, it would take another year for most POWs to be repatriated back to Germany. (This special camp is the subject of a detailed article on this website and is the website’s most widely read article; see the link at the end of this article).

The Sheldon family soon became friends with Captain Robert Kunzig, the camp’s commander, and Lieutenant Robert Pestalozzi, a favorite of the POWs. Both men were very talented and helped to make the camp at Fort Kearney a significant success. Betty and Louise recalled that Kunzig and Pestalozzi each spoke fluent German and loved their jobs. Marjorie often invited the captain and the lieutenant to Spindrift for dinner. Afterward they would all join in singing songs, with Kunzig pounding away at the piano and Pestalozzi playing the accordion. Sometimes Pestalozzi, whose family hailed from Switzerland, would yodel. Everyone enjoyed these times. Once a POW driver picked up Captain Kunzig from Spindrift; the driver was trusted enough to go outside the prison camp (recall the war with Germany had ended). Once the Sheldons were invited to the camp where they were served a fine dinner cooked by the POW chef and attended by a waiter who was also a POW.

Betty continued to write letters to Jim when she could. Once she included in the letters black-and-white photographs of her in a swimsuit, pretending to be a Polynesian woman. Jim reveled in it. He also sent his fiancé a brand new replacement leather flight jacket. But Betty had a bad premonition. Jim was flying missions in a dangerous place.

Forbes Whiteside, Jim Bistodeau, and Lester Placke (a fellow pilot) enjoy some frolicking at Spindrift after helping to clean damage there caused by the September 14, 1944, hurricane (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman)

As the summer wore on, it became clear that the United States would soon win the war against Japan, ending the long nightmare that was World War II. Then all the servicemen could come back home, including, among millions of others, Jim, Otho and Forbes.

Finally, on August 15, the victory over Japan was announced. Everyone was jubilant. Marjorie announced she would have a party that evening, and she and her daughters invited over their friends. It was a grand event.

During the party Betty was informed that there was a telephone call for her upstairs; it was urgent. She rushed upstairs, not knowing what to expect. It was a Navy Department official on the line. Jim and his PBM were missing, the voice at the other end of the line said. Jim had been piloting a PBM over Formosa on August 8, but he and his aircraft never returned. Of course, the implication was that he could be dead. Stunned, Betty put the receiver back down on the phone. A lump developed in her throat and she felt ill. But she decided not to tell anyone at the party downstairs. She did not want to spoil the gay mood at the party. Let them enjoy this memorable night. But for Betty, the night was memorable for another reason.

Betty would learn later that both Jim, and his friend Otho, were killed that August 8. She pieced together what happened from a newspaper report that summarized a letter from the Navy department sent to the parents of Otho, who had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal, and a letter from Forbes Whiteside. Forbes, who also received the Distinguished Flying Cross, once spent six days in a raft with his flight crew after the successful ditching of their disabled PBM, and another time had flown over the Japanese city of Nagasaki following the dropping of the second atomic bomb.

On that fateful night of August 8, Jim and Otho flew one PBM and a newer (but still experienced) crew flew another. They took off from the Sakishima Islands, searching for enemy vessels supplying or supporting Japanese troops on nearby Formosa. At about 7:30 p.m., they attacked three enemy motor torpedo boats, forcing them onto the beach. After reporting that incident and stating that the two PBMs were continuing their mission, no word was heard from either plane again. Eleven days later, the only trace of the missing planes was a PBM wing found floating in the water. Eventually, one of the wrecked PBMs was located in the ocean and pulled ashore. Forbes Whiteside thought that the only explanation that made sense was that the two PBMs had accidentally collided. He wrote to Betty, “All the night flights were made without running lights on the planes.” “The most likely conclusion that anyone has drawn,” he continued, was that flying in the “pitch black the two planes collided and crashed so quickly that the radioman hadn’t time to even begin a message.”

All twenty-two crewmen on the two PBMs were presumed dead. It is doubtful any of their bodies were ever recovered.

The grieving Betty took some consolation sailing her boat on Narragansett Bay. That summer, she frequently took Captain Kunzig sailing. One day, Kunzig confided to her that he was nervous about an upcoming visit by Major General John Hildring, who would be inspecting Fort Kearney. If the visit went well, maybe Kunzig would be promoted. Kunzig thought it would be a grand idea if he took General Hildring sailing. He was sure the general would enjoy it. Kunzig had his own boat he could use.

Several days prior to the General Hildring’s inspection, Kunzig sailed to Spindrift and left his sailboat at the dock. He had dinner at the house as usual and played piano for the Sheldon family. As darkness fell, he decided to leave his boat behind and be driven back to Fort Kearney. But that night a storm kicked up and seriously damaged Kunzig’s boat. Betty suggested he bring it to the Perkins & Vaughan shipyard in Wickford for repairs. Kunzig was keen to have his boat’s repairs finished before Hildring’s visit, but due to unavoidable delays, his boat was not repaired in time for the day of the big inspection.

Betty felt bad about the boat being out of service and desperately wanted to help her friend, Captain Kunizg. She decided she would sail her own sailboat Sirocco down to Fort Kearney and let Kunzig use it to take General Hildring out for a sail. She set out in her boat from Saunderstown for the one-mile trip. Back at Fort Kearney, Captain Kunzig sat with General Hildring on the porch of the captain’s yellow headquarters building, both enjoying the cool breeze and spectacular view. Kunzig was then surprised to see Betty sailing down toward Fort Kearney in her Lawley. He was even more surprised, shocked actually, when Betty brought her sailboat to the dock at Fort Kearney, tied it up, and dove into the bay, apparently with the intent of swimming the one mile back to Spindrift. Now he became worried. He called for immediate assistance, requesting a motor boat be sent to rescue Betty. But Betty knew what she was doing. She had timed her trip so that the tide would take her back up to Saunderstown.

Bette Sheldon wearing the flight jacket Jim gave to her in 1945, circa 1948 (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman)

Soon the summer of 1945 came to an end. The days of World War II, when so many contributed toward the common goal of defeating the Axis powers, were gone forever.

After graduating from Bryn Mawr with a major in chemistry, Betty became an airline stewardess for TWA, when civilian flight was in its infant stages, and was excited to fly overseas. Once during a layover in Minneapolis, Minnesota, she was invited to see Jim Bistodeau’s parents. She agreed and they could not have been nicer to her. She also received heartfelt letters from Otho Edwards’ parents.

Betty and her younger sister Louise still live full lives. Betty married a business manager and lived many years in Hartford and then Florida. Louise became a magazine reporter in Europe and then a foreign correspondent for United Press International, spurred by her exposure to German culture in Narragansett Bay.

Betty Sheldon waving at a World War II vintage Liberty Ship steaming up Narragansett Bay, September 2010 (Collection of Marjorie Johnston)

Happily, both of them frequently visited Spindrift in the summers. Betty and her husband built a house next door to Spindrift after it was sold. Now 93-years-old, she lives in Wakefield near her daughters and son. Louise has lived in Arizona for several years, but still has a condominium with a water view in Hamilton outside Wickford that she and husband often enjoy. Forbes Whiteside became an artist of some renown and passed away at age 96 in 2015.

Bette kept Jim’s flight jacket all these years. She wore it often, as did her children and a nephew. Despite all the wear, Betty’s repairs to the jacket, and the passage of 72 years, there remains in one of its pockets a note from Jim Bistodeau to Betty. It says: “Hope this is all right honey. It’s a nice new one—not battle worn like the other. Love, Jim.”

Recent photo showing Jim Bistodeau’s flight jacket, two wartime photos of Jim, and the letter Jim sent to Betty accompanying the flight jacket in 1945. Betty carefully preserved and kept all of the items (Theodore Aschman)

[Banner image: Recent photo showing Jim Bistodeau’s flight jacket, two wartime photos of Jim, and the letter Jim sent to Betty accompanying the flight jacket in 1945. Betty carefully preserved and kept all of the items.]

Bibliography

Elisabeth Kellog Sheldon Aschman interview with the author, May 28, 2016.

Elisabeth K. Sheldon Sailing Permit, June 6, 1944 (Collection of Betty Kellogg Sheldon Aschman).

Louise ( Lulu) Roberts Sheldon MacDonald, e-mail to the author, April 18, 2016, and interview with author, August 8, 2016.

Louise Sheldon MacDonald, “Encounters with Myself” (draft of autobiography, circa 2016).

News clippings of two stories, in unidentified newspapers, probably dated some time in 1945, one announcing the death of Jim Bistodeau and the other the death of Otho Edwards; photographs of family and friends from 1944 at Spindrift and nearby locations, all in a scrapbook of Elisabeth K. Sheldon (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman).

Letter from Forbes Whiteside to Betty Sheldon, October 3, 1945 (Collection of Elisabeth Kellogg Sheldon Aschman).

Christian McBurney and Brian L. Wallin, “The Top Secret World War II Prisoner-of-War Camp at Fort Kearney in Narragansett” in The Online Review of Rhode Island History (April 22, 2015). Here is the link to the article:

The author thanks Marjorie Johnston, Betty’s daughter, of Wakefield, for gathering the images for this article and for reviewing drafts of the article for accuracy.