Elisha Potter, Jr. was the son of prominent attorney and Rhode Island politician Elisha Potter, Sr. and his wife Mary (Mawney) Potter. As a young man, Elisha Jr. grew up in a life of privilege on the family’s Kingston homestead (which still stands) and nearby farms. He was well educated, attending the local Kingston Academy and then Harvard University, graduating in 1830. In the wake of his formal education, Potter headed to Washington, D.C. where he observed “the activities and dynamics of the United States Congress.”[1] This was his entry into a lifelong interest in politics, which were coupled with the young man’s interest and enthusiasm for agricultural improvement and for local history.

When Potter was just twenty-four years old, the Rhode Island Historical Society published his Early History of Narragansett, which was not a historical narrative so much as a collection of documents, letters and deeds from the seventeenth century that together, compiled the history the Narragansett tribe and the early white settlers in the region now known as South County.[2]

The Potter Homestead, built by Elisha R. Potter, Sr. in 1809 and headed by him until his death in 1835, and resided in by Elisha R. Potter, Jr. for most of his life from 1811 to 1882 (Old Houses in the South County of Rhode Island, circa 1932)

Potter worked during an era I termed the ghosting of a people which began after the Revolutionary War and culminated in the detribalization of the Narragansett by Rhode Island in 1887. Such a ghosting began when census takers began to record Narragansett tribal members with a distinctly paternalistic view. In those years after the war, Narragansett women subjected to servitude for debt or some determined petty crime often shared household duties with enslaved Blacks and they began to intermarry and have children.

The State determined that the race of the children of all these unions was determined by the race of their father. In what Narragansett historian Everett Tall Oak Weeden described as a “paper genocide”, the matriarchal tradition of the tribe was put aside. Those children in census after census during the nineteenth century were thus assigned another race, and so the population that the state identified as Narragansett increasingly dwindled through the decades. For the Rhode Island government, and indeed, much of the white population, the Narragansett, by and large were a people of the past.[3]

This notion was reinforced by the migration of some Narragansett tribal members who had been Christianized who followed Mohegan minister Samuel Occom to Oneida, New York in 1774 and later years. Here they joined other Christian members of the Mohegan, Pequot, Montauk, Natnick, and Shinicook tribes in settling their own community on Oneida lands. This community would eventually migrate to Wisconsin in the 1830s. Some other Narragansetts removed to neighboring “cousin” tribes such as the Hassanamisco band of the Nipmuc Indians in Massachusetts[4] and the Niantic in Connecticut.[5]

Samson Occum, the Mohegan founder and first leader of the Brothertown settlement of New England Indians (National Portrait Gallery)

The absence of so many Narragansetts from their homelands in Rhode Island was interpreted by the white population to mean that those who remained on and off tribal lands, often living in abject poverty, were the remnants of what once had been a noble people. This was a common assessment by historians, the general population, and especially politicians of the nineteenth century, who felt the state had waited long enough for the tribal members to abandon their ways and integrate into the white society that surrounded the reservation on which they had been placed over a century earlier. Of course, tribal members had no desire to abandon their beliefs, culture, or lands. Other tribal members eked out a living working outside their community, but they also worked to keep their indigenous community and culture intact.

Elisha Potter, Jr.’s involvement in state politics increased after the death of his father in 1835, the same year his Narragansett history was published. Thereafter, his political career and the duties in which he engaged often led him to be engaged with tribal members. He was an assistant for the state Secretary of State from 1831 to 1833 and held the position of Rhode Island Adjunct General in 1835 and 1836.

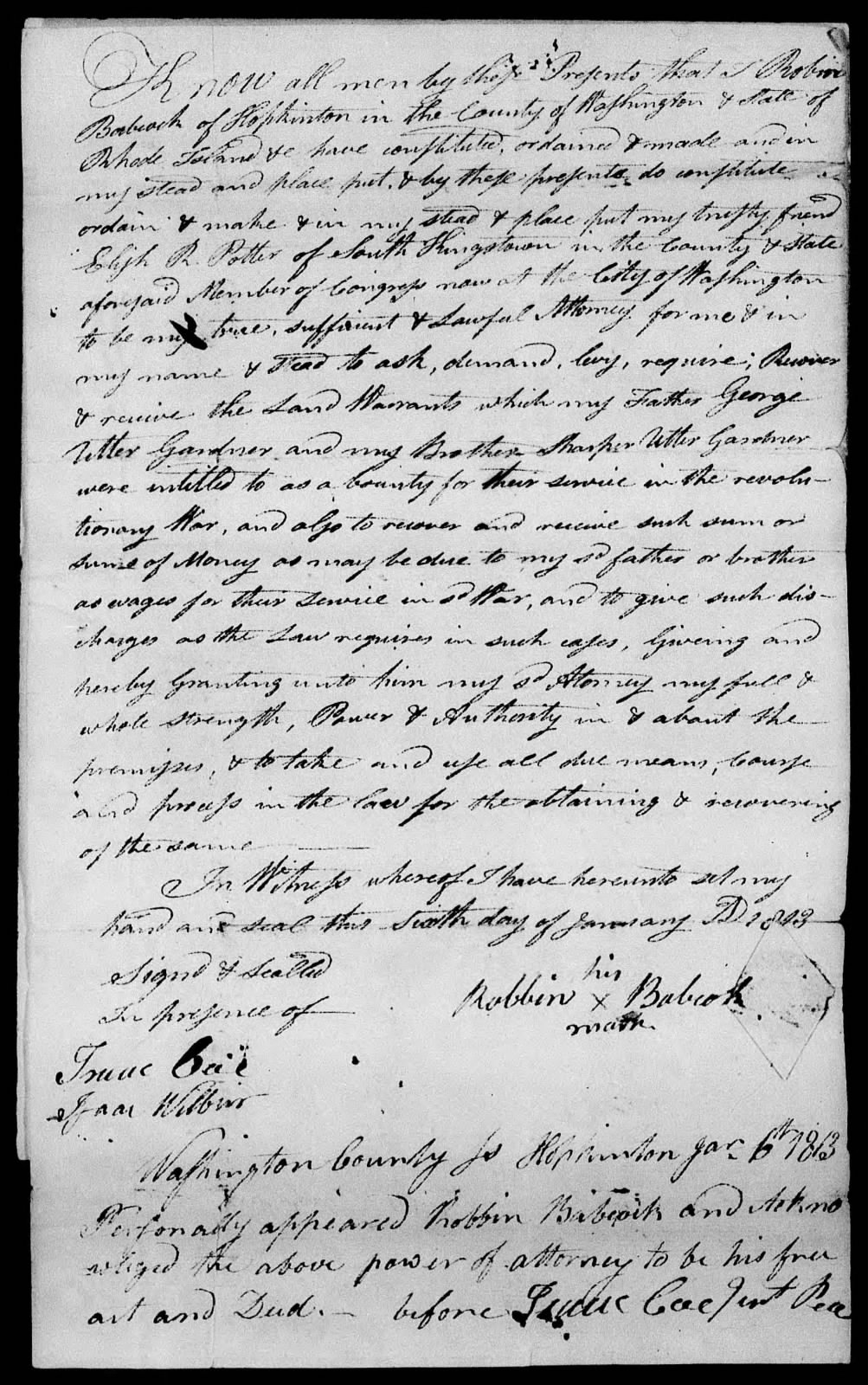

Potter was already familiar with tribal claims. The work he commenced in his youth collecting deeds, documents and correspondence lent him a familiarity that was called upon throughout his long career. He must have also been aware of his father’s role representing Narragansett claims such as the land claims sought by the Gardner family.

A Narragansett, Robin Babcock, hired Elisha R. Potter, Sr. to serve as:

“my true, sufficient & Lawful Attorney for me in my name & stead to ask, demand, levy, require, Recover & receive the Land Warrants which my Father George Utter Gardner and my brother Sharper Utter Gardner were intitled to as a bounty for their service in the Revolutionary War, and also to recover and receive any sum…of money as may be due to my father or brother as wages for their service in said War, and to give such discharge as the law requires in such cases….”[6]

With Potter’s assistance, in December of 1813, the Department of War ruled that the father and son had indeed served throughout the war. The surviving family member was then awarded the land grant that the father and son had earned from their military service.[7]

Declaration by Robin Babcock to support his claim, and that of his brother and sister, to warrants for land awarded to their father and brother, both Revolutionary War veterans in the First Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals (Sharper Utter Gardner Pension Application, Revolutionary War, National Archives).

Narragansett law for tribal lands was clearly stated by sachem Augustus Harry in an 1820 letter sent to federal authorities who had deemed that land “owned” by a disabled veteran disqualified him from the pension he had requested for time served during the Revolutionary War on account of his being financially destitute:

“The Council of the Tribe, who are annually elected, superintend & direct the Municipal Concerns of the Tribe, according to the Customs and Usages of said Tribe, particularly the letting out and leasing of the Lands belonging to said Tribe, and of the individuals who choose to Let their Lands. The Narragansett Tribe, and the individuals thereof, hold their land in a tenure peculiar to themselves. Not as the white People hold lands.

An individual of said Tribe cannot sell or convey any Land descended to him or her, nor mortgage it, or charge it with Debts as white people do. But when a Member of that Tribe dies, his or her Land descends to his or her Children or next of kin, generally without distinction of Male or Female, and if a member of the Tribe abandons their land and goes without the [e]state, the next Heirs or Heir enters & occupies it.

Neither can a member of said Tribe lease out or let his or her land without the approbation and Signatures of a Majority of the Indian Council. Neither can a Member of the Tribe dispose of his or her land by Will as white people do.

I further testify that John Harry… is very poor. I believe him destitute of property, quite infirm, and unable to do hard labor. He sometimes performs some light work for which he receives some Compensation, but at present is principally supported by his Children who labor for their Support.”[8]

In the ensuing years, reports concerning the dwindling numbers of tribal members on the reservation, and the decrepit condition of much of the land began to be filtered to both the public and the General Assembly. The failure of “Indian schools” on the tribal land led to exasperated letters from the Baptist missionaries attempting to Christianize those tribal members who remained.

Attempts to “regulate the Publick Affairs of the Narragansett Tribe of Indians” by the General Assembly began in 1792 with an act appointing a treasurer to oversee land claims. The Assembly determined that any future lease of lands had to be approved by both the Narragansett Council, and the governing committee overseeing the tribe, and appointed a treasurer to account for any such transactions.[9]

A census ordered by the governing body in 1833 found 199 families currently living in Charlestown, with 50 or more names of people “who were supposedly absent.”

In 1836 the General Assembly appointed a committee to address the “business of the Narragansett Tribe.” Elisha R. Potter, Jr. was appointed to this committee, which determined regulations for land claims. The committee also directly addressed those who had moved out of state:

“If any Indian or Indians remove from the tribe to the Oneida nation, or other Indian nation for settlement, he or they so removing, shall not have the privilege of leasing his or their lands for any longer term than six years, and at the end of six years, the lands shall be improved by the heir or heirs of the person so remaining; and in case no heir or heirs be left, the lands to be rented by the council and appropriated by the treasurer; the rents arising therefrom, to be appropriated to and for the use of the poor of said tribe.”[10]

That year Potter began a correspondence with Tobias Ross, a Narragansett who, with others, were anxious about the settlement of land claims. In one letter, Ross writes, “Do not fail of meeting soon, as the tribe is very anxious for you to meet and do business for them …. [I]f you do not meet it will be a great damage to the tribe and more so to myself.”[11]

Potter issued a report to the General Assembly in January 1839 and did not equivocate about the rights of the indigenous people and their concerns:

“The complaints made by members of the tribe may be reduced to a few heads. First, trespasses committed upon their lands by the white people, and the difficulty of ascertaining and settling the title to their lands. The title of the Tribe to the lands they hold, rests upon their ancient and undisputed possession…. The land thus reserved has been repeatedly confirmed to them by acts of the Assembly, and of course all of it now belongs to them, except what has been legally sold out of it….

“The records of the Assembly shew, that the Indians have been continually complaining of the encroachments of the white people upon them…. The present act for preventing trespasses on Indian lands by white people, is of no effect, as it requires actions therefor, to be commenced in the name of the “treasurer of the Tribe”, and there is no such officer.

“There is a great deal of imposition practiced upon the tribe by carrying off their wood, or pretending to buy it of those who have no right to sell it, cannot be doubted. It can only be prevented by a law with severe penalties.”

“Another source of difficulty is their not being guided by any certain rules regulating the descent of property, and the right of membership of the tribe. These things have generally been governed by custom; explained in case of doubt, by the authority of their council.”[12]

The 1839 report also makes clear that many Rhode Islanders by this time viewed the Narragansett as little more than a nuisance, with their empathy reserved not for those impoverished who wished to sell their lands and improve their lives, but to those white landowners who surrounded the reservation:

“The state of morals among the Indians has, for many years, been very low, and it has a debasing effect upon many of the white people near them. The people of their neighborhood will, undoubtably rejoice to have them better educated, and their morals, if possibly improved, as the only way of correcting the evils they must otherwise suffer from, in consequence of their presence.”[13]

Alcoholism was once again raised as an issue, one that had been addressed in the Assembly as early as 1718. In the 1839 report, Potter believed the only recourse to protect the indigenous people from the ravages of alcohol and the debts to which those addicted became hopelessly tied was as follows:

“There ought to be a law to protect them against debts contracted for spirituous liquors and if any person who knowing their ignorance and propensities, furnished them with intoxicating drink, could be made liable for all damages, assaults, perjuries, or other crimes they might cause or commit while under its influences, it would perhaps be no more than equal justice.”[14]

Perhaps the greatest challenge of indigenous land claims in the state were those politicians who, persuaded by the Brothertown faction, believed that the future of the Narragansett Tribe lay with those members who had removed from Rhode Island. As the greater majority of these claims sought to sell the land of their ancestors, and thus sell land the state viewed as part of the reservation, whether the sale was made to an indigenous tribal member or an outsider opened the risk of forfeiting yet more Narragansett land.

During the next few years, Potter handled several cases on behalf of Narragansett men and women. He recognized that the restrictive 1792 Act to regulate the Narragansett, and the appointment of a treasurer as overseer, were missteps. In criticizing the 1792 Act, he noted that:

“One of them… introduces, among the Indians, the statute rules of descent; thus virtually doing away with any rules derived from their old customs and usages. But since the discontinuance of the office of treasurer, who acted generally as a sort of overseer of the tribe, the council has managed these things, according to their own will and pleasure.”[15]

Potter assisted Matilda Rodman, a Narragansett woman, in petitioning the General Assembly for her right to sell 45 acres of her land on the reservation. He also corresponded with Moses Stanton on his petition for the right to sell land so that he might move to Green Bay, Wisconsin (near the Brothertown settlement). Potter’s papers also hold correspondence from those years with Elizabeth Primus, who was attempting to claim land that had once belonged to her grandmother.[16]

In 1843 Potter attended a meeting in the Narragansett Church that was held, as reported in the August 14, 1843 edition of the Providence Journal, amid the large annual August gathering. He was there, as “the General Assembly has been informed that a number of the tribe wished to have liberty to sell their lands and emigrate…their land here was poor and exhausted; the land of Green Bay, where their brethren were, was of the most exuberant fertility.”[17]

Likely in an effort to enlighten the governor of Rhode Island to the tribe’s plight, the Narragansett invited Governor John Brown Francis to attend the August meeting. His response was to write send the invitation back to Potter with a terse note that made clear his sentiments on the present state of the tribe: “What’s this great Indian Pow-Wow?”, he demanded, “I thought the tribe were Negroes.”[18]

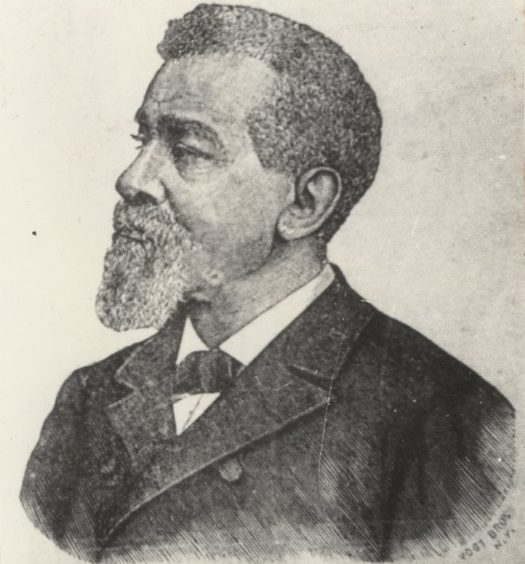

Perhaps the most challenging and unusual claim came from a Narragansett man named Thomas Commuck. Commuck had first written to Wilkins Updike on July 14, 1839:

“Sir, the undersigned in compliance with the wishes of Moses Stanton of Charlestown R.I. takes this method to inform you that I am one of the very few full-blooded remnants of that once numerous and powerful tribe known by the name of the Narragansett Tribe of Indians.

My object in writing to you is to get your candid opinion respecting a claim that I have towards land lying in the town of Charlestown, R.I. I am the only legal heir to my Grandfather Joseph Commuck’s farm, he has no son or daughter, Brother or Sister living and no other grand child except myself. He (?) at his Death a farm containing about 150 acres as I always understood, but I believe that Moses Stanton estimated it at only about 120 acres said land be it more or less, descends in a direct line to me- for the last two or three years I have become anxious to sell the same so that I may be certified thereby…I think it was in 1823 that I travelled into State of New York and lived among the Brothertown Indians and was adopted into their nation as you know that all Eastern Indians have been by them. The said Brotherton Indians being composed of various Indian tribes or rather, the descendants of such.

At the time of my leaving R.I. my Grandfather’s farm was leased by Daniel Sekatur, a resident in Charlestown. Since the expiration of said lease, I do not know many of the particulars respecting whose hands said land have been in, but I have understood that Jerusha Hull – a woman who claimed to be half sister to my grandfather has held possession of said land. She is now dead- I have written several letters to Moses Stanton who is well acquainted with the Justice of my claim to him. I would respectfully refer you for any particulars respecting my claim-being but a mere lad when I left Charlestown I was but very imperfectly acquainted with the laws, rules, and regulations of said tribe-but as near as I can I think that I could not sell said land without getting a special act passed by the legislation of R.I. to that effect….

I have written to the governor of the state of R.I. day before yesterday. I received his answer, he says that he thinks by petitioning the legislature of the State of R.I., I shall have a special act passed for my relief—therein is our point which I wish to be particularly instructed in—because I think that it may have a very important bearing upon the Situation, that is Congress passed a law last winter authorizing that the Brothertown Indians be admitted as Citizens of the U.S. to all intensive purposes so that they have the title to their lands in Wisconsin Territory licensed to them …. [Y]ou are no doubt acquainted with the Bill of which I speak and all of its provisions. You will perceive then that I am soon to be a citizen of the U.S. and I believe that the Constitution of the U.S. provides that no man shall be deprived of his just rights. I wish you to give me your opinion on that point in particular.

If you can assist me in selling said lands I will reward you amply for your trouble. I wish that you could consult with Moses Stanton on the subject and act in concert, he being one of the principal councilmen in Charlestown…. I think of coming down to Charlestown if it is necessary to endeavor to secure my Just Rights but the road is a long one and I don’t wish to come until I am certainly informed whether I can sell or not. 1,600 miles cannot be travelled without a considerable sum of money to defray expenses & that is the distance I should have to travel should I come.”[19]

Thomas Commuck was born in Charlestown, Rhode Island, in 1804. He mentions that his family moved to Oneida, the original home of the Brotherton Indians, when he was a boy. He moved to Wisconsin with others of the community in 1825. In 1831 he received in Wisconsin half the lot his family owned and the right to sell that parcel which allowed him to remain in Wisconsin. He married Hannah Abigail Abner on July 31, 1831. The couple would have ten children together.[20]

Commuck and other Narragansett who sought rights to lands their families had once held, clearly had an uphill battle before them. Wilkins Updike, who then lived in Kingston, Rhode Island, passed the letter on to his neighbor, Elisha Potter Jr.

It seems that Potter and Commuck entered into communication thereafter, but the case seems to have languished. In Potter’s papers, we find the next communication to the attorney from Commuck to be a letter dated July 11, 1844, and, remarkably, written almost entirely in verse:

“1. Once more I ask how do you do?

Tis’ long since I have heard from you,

Which leads me (rather right or not)

To think that you have me forgot.

- Myself and family, are well.

Which I do with much pleasure tell.

And when these feeble lines you view,

I hope twill’ be the same with you.

- I often think with heaving breast

Of Rights, which Wrongly are possessed.

And often to, have I implored,

That they might be, to me restored.

- I sought your aid, you promised to,

That you would try, what you could do.

That you my case would take in hand,

And help me this, to gain my land.

- I know objections have been brought

But all their weight, and force, is naught.

Justice and truth, are on my side,

Although my Rights, have been denied.

- Some say one thing, some say another,

Some slander my Father and my Mother.

Some say “They never married, were,

Therefore, he’s not the legal heir.”

- I join the issue with them here

And soon, will prove my title clear.

I’ll take the law of common sense,

Which legal is to all intents.

- My Father lived with Mother dear,

Till’ Death’s grim monster did appear,

And cut the silver chord of life,

By which she ceased to be his wife.

- Two affidavits I did send,

To Moses Stanton, my old friend,

Who says he left them in your hand,

That you my case might understand.

- Examine them and Judge ye (whither

Or not) you’ll see, it was together

They lived, ‘till Death interceded there,

Therefore, I am the legal heir.

- To here I let the matter rest

And hope you’ll try to do your best,

And to reward you for your toil,

I with you, will divide the Spoil.

- So please to write and let me know

Which way my case is like to go.

Six weeks from this I hope the mail

Will bring your answer without fail.

- So now I must come to a close

But let me first, one thing propose

Which is, Pray don’t offended be,

For writing in this style to thee.”[21]

The letter was sent with a document from the Governor of Wisconsin, which states in part to Thomas Commuck that, “The facts stated by you in your letter of the 20th . . . appear to me to be conclusive to establish your right to be regarded as the heir of successor of your Grandfather in Rhode Island.” Regarding this document, Commuck explained to Potter:

“Dear Sir, I have taken the Liberty to inclose to the committee of whom you are a member, the foregoing letter from his excellency J.D. Doty, Governor of Wisconsin Territory. I will just say that his opinion is worthy of Consideration as he is a gentleman of high legal attainments, having practiced for many years at the Bar, and he is intimately acquainted with all laws and customs in regard to Indians and their titles to land. Moses Stanton has affidavits showing that my father and mother lived together as man and wife until the Death of the Latter.”[22]

Despite the governor’s view (which, admittedly, was not an official ruling), the case continued to languish, and ties to the community where Commuck and other Narragansetts had settled in Wisconsin kept him from bringing his case in person.

In a postscript to Potter, Commuck added:

“…in order to save postage as much as possible, probably we had better write as often as we can, For I shall soon have to resign my office as Post Master, in consequence of my now being a candidate for member of the House of Representatives of this Territory. The election comes off in September next. This is something I never expected, and I objected against it all I could, but my friends in this region are determined that I shall fill this important place, and if elected, I shall have to stand it.”[23]

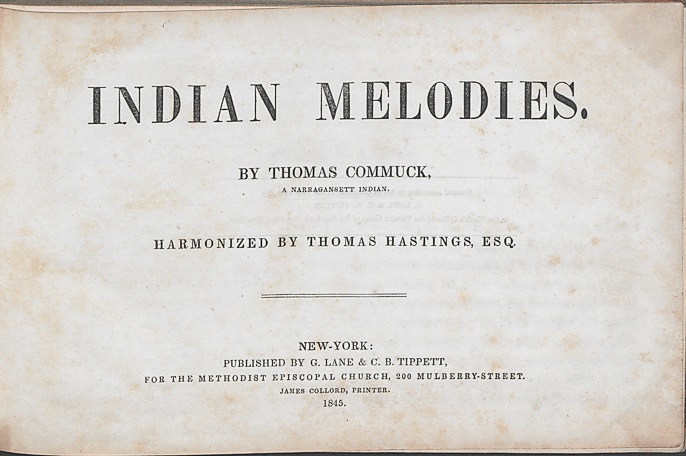

Elisha Potter Jr. likely did not know of his client’s extraordinary life beyond the land claim in Westerly. Had he an inkling of Commuck’s life, he would not have been surprised by the letter in verse, for Thomas Commuck was to publish the first book of indigenous hymns, entitled Indian Melodies, the following year. A collection of learned songs and hymns mostly written by Commuck, the Indian Melodies are “both religious and richly expressive and their context consists of everyday life, hardships, harmony, and the connection one has with a higher power.”[24]

The hymnist was unafraid to distinguish himself and his brethren from other Christians in Wisconsin and other parts of the United States. He writes clearly, describing himself as

“having been born, not only in obscurity, but being descended from that unfortunate and proscribed people, the Indians, with whose name a considerable portioned of the enlightened American people are unwilling to associate.”

At first glance, it might appear that Commuck had become the “Indian” that most Rhode Islanders hoped all Narragansetts would become: Christianized and compliant with the continued marginalization of indigenous language, culture, and practices. Still, Thomas Commuck’s conversion, and others of his people, did not lead to a loss of indigenous identity. In his introduction, Commuck tells the reader:

“As the tunes in this book are the work of an Indian…the tunes themselves will be found to assume the names of noted Indian chiefs, Indian females, Indian names of places, &c. This has been done merely as a tribute of respect to the memory of some tribes that are now nearly if not quite extinct; also as a mark of courtesy to some tribes with whom the author is acquainted.”[25]

Indeed, the verses of Indian Melodies are deeply imbedded in nature and the belief that an earth spirit dwells in native believers, even as they look towards heaven:

“Thus on the heavenly hills

The saints are blessed above

Where joy, like morning dew distills

And all the air is love.”[26]

Thomas Commuck continued to write and see his work published. By 1855 he had written Sketch of the Brothertown Indians for the Wisconsin Historical Society, of which he was an active member and friend. The postscript to the pamphlet that was published posthumously in 1859, reads:

“POOR COMMUCK! The following winter after penning the preceding sketch, he was drowned, in a hole in the ice, near his residence, in Calumet County – whether by accident or design is not known…. He was a true friend of the Historical Society; and had he lived a few years longer he would doubtless have contributed additional papers of historic interest. His love for preserving the history of his people, should shame many a white man…”[27]

Meanwhile, after leaving politics behind and devoting much of his time to the law and advancement of education, Elisha Potter, Jr. was consulted numerous times on “Indian Affairs.” In 1848, Potter was appointed Rhode Island Superintendent of Public Schools, a post he was to hold for the next six years. During that time, he continued receiving letters from the public and state officials concerning indigenous matters.

John Stanton, his replacement as the State’s delegate to the Tribe, wrote in May of 1850 concerning a “young Indian from Michigan, who is now making some inquiries relative to his claim to certain lands in the Narragansett Tribe.”[28] The claim, like others, involved land that had been leased by the family, but confiscated after ten years when no heirs were found that could lay claim to the property.

Stanton acknowledged that “there are a number of claims of the same description already presented and many more no doubt waiting the result of these.” Stanton questioned whether “the makers of that law meant to exclude at the end of those ten years, all heirs who were not at that time in the Narragansett Tribe. I suppose the question and upon which of course you are a better judge than myself….”[29]

Potter’s response was a clear outline of how he had proceeded with these cases over the years:

“I have endeavored to give the question you proposed some consideration.

Taking all the laws together it seems that it has always been the policy of our government to consider the Indians as entitled only to a sort of use of the land…. And they have never been allowed to sell without a special grant.

The permission to lease for a certain number of years was given I suppose to aid those who were desirous of emigrating to the Oneidas. If they do not return in a certain time the tribe is there to lease the land to support their poor. But if the heirs choose to return and live here, I see nothing to prevent their occupying the land again.”[30]

In December 1850, Potter was requested to contribute to a report on the “poor and paupers of the State” led by Thomas R. Hazard of South Kingstown. “Will you be so kind as to let me know something of the situation of the Indians in Charlestown?,” Hazard wrote. He added: “What is their condition as to property? Is what they have well secured to them by law? Can it be plundered by the whites?” Hazard’s also asked about lease rights.[31] Clearly, Potter was the white person who had the greatest knowledge of indigenous affairs

By 1852, the Assembly had formed a committee to begin looking into the process by which the State could terminate the tribe’s legal status (or “detribalize” the Narragansett). This act began a long process whereby proposals and reports led to various early attempts in 1857, two years later in 1859, and again in 1866, to achieve that purpose.[32]

For Elisha Potter Jr. and other white residents of Rhode Island, the Narragansett seemed to have improved their situation since the 1839 report. The state had continued to support a school on the reservation, and a religious revival in 1859, led by Narragansett minister Aaron Sekator, resulted in the construction of a stone church (which still stands on Narragansett land) and a new congregation of Second Adventists that replaced the old Baptist church established by Samuel Niles in the mid eighteenth century.

Such seeming assimilation into white culture propelled the state’s politicians into pressing for detribalization. The General Assembly formally began to hold hearings on abolishing tribal relations and making the remaining Narragansett citizens of Rhode Island in 1879. The five tribal members who had been appointed to the council vehemently opposed the State’s plan.

Nonetheless in 1880, the General Assembly passed legislation to abolish the tribal authority and declared tribal members to be citizens. The act authorized all lands “held in common”, if sold, to result in proceeds being distributed among tribal members. Any lands held individually would be deeded to those indigenous land holders.[33]

The effect of the State’s action resulted in the loss of nearly all the 927 acres held in common, leaving only the two acres surrounding the stone church. Despite this devastating loss, a sizable and resilient group of Narragansett remained in their homeland. Their descendants would see the day in the late twentieth century when tribal recognition occurred and the reservation lands were returned to the tribe by the Federal and State governments.

Notes:

[1] Elisha R. Potter Jr. Papers overview, Rhode Island Historical Society, at https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/Mss629-3.htm; see also Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Kingston, R.I.: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 190-95 and 220-25. [2] Elisha R. Potter, Jr., The Early History of Narragansett, in Collections of the Rhode-Island Historical Society, vol. 3 (Providence: Marshall, Brown and Company, 1835). [3] Robert A. Geake A History of the Narragansett Tribe (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011), 94-97. [4] Duane Reed, “A Walk on Narragansett Land Ark,” Republic, 2023, atSee https://www.arkrepublic.com/2023/11/25/a-walk-on-narragansett-land-exploring-how-native-american-heritage-centers-the-original-american-holiday-season/, accessed Dec. 26. 2024.

[5] For more on the Brothertown Native Americans, see William DeLoss Love, Samson Occum and the Christian Indians of New England (Boston: Pilgrim Press, 1899). [6] See Robin Babcock Declaration, Jan. 6, 1813, in Sharper Utter Gardner Pension Application, Revolutionary War Pension Applications, Rhode Island, Record Group 15, M804, National Archives. [7] See George Utter Gardner and Sharper Utter Gardner Pension Applications in ibid. [8] Quoted in Robert A. Geake, “Indigenous Soldiers of the Revolution and their Fight to Obtain Pensions for their Service,” The Cocumscussoc Review (November 2022); John Harry Pension Application, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Application Files, M804, Roll 1206, 10, National Archives. [9] The Narragansett Indians, 20 RI 715 (R.I. 1898). [10] Ibid., 748, [11] Elisha R. Potter, Jr. to Tobias Ross, September 10, 1836, Elisha R. Potter Jr. Papers, Mss 629, sg3, Series 1. Box 1, Folder 2, 1835-1838 Rhode Island Historical Society. [12] Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly, 1838-1839 (Providence, R.I. 1840), 30-31. [13] See Robert A. Geake, A History of the Narragansett Tribe: Keepers of the Bay (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2011), 90. [14] Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly,1838-39, 31. [15] Ibid., 32. [16] Petition of Matilda Rodman to the General Assembly, 23 June 1842. Mss 629, sg 3, Series 1. Box 1, Folder 7 1842. [17] Geake, A History of the Narragansett Tribe, 90. [18] John Brown Francis to Elisha R. Potter, Jr., August 8, 1843, Mss 629, sg3, Series 1, Box 1, folder 9, 1843 August – December Correspondence, Rhode Island Historical Society. [19] Thomas Commuck to Wilkins Updike, July 14, 1839, Elisha R. Potter Jr. Papers, Mss 629, sg3, Series 1, Box 1, folder 11. [20] James Phillip Page, Thomas Commuck and his Indian Melodies: Wisconsin’s shape Note Music Book, https://brothertowncitizen.wordpress.com/thomas-commuck-and-his-indian-melodies-wisconsins-shape-note-tunebook/, Accessed Dec. 14, 2024. [21] Thomas Commuck to Elisha R. Potter, Jr., Elisha R. Potter Jr. Papers, July 11, 1844, in Mss 629, sg3, Series 1, Box 1, folder 12, Rhode Island Historical Society. [22] Ibid. [23] Ibid. [24] See Thomas Commuck, Indian Melodies (1845) in Dawnland Voices: Writings of Indigenous New England https://dawnlandvoices.org/collections, Accessed Dec. 13, 2024. [25] Ibid. [26] Ibid., 10. [27] Thomas Commuck, “Sketch of the Brothertown Indians,” Wisconsin Historical Collections (1859), at http://www.marshallhistsoc.org/brothertown/bro_commuck.html. [28] John Stanton to Elisha R. Potter, Jr., May 28, 1850, Elisha R. Potter Jr Papers, Mss 629, sg3, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 2, 1849-1850 Correspondence, Rhode Island Historical Society. [29] Ibid. [30] Elisha R. Potter, Jr. to John Stanton, May 28, 1850, in ibid. [31] Thomas R. Hazard to Elisha R. Potter, Jr., December 18, 1850, Elisha R. Potter Jr. Papers, Mss 629, sg 3, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 2, 1849-1850 Correspondence, Rhode Island Historical Society. [32] Never long away from politics, Elisha R. Potter, Jr. declared himself a candidate for governor in both 1858 and 1859, but was soundly defeated. He seems to have suffered from a financial setback as well over the next few years, relying upon friends and old clients to obtain a legal position for him in Newport. He was appointed a justice on the Rhode Island Supreme Court in 1868 and held that position for the next fourteen years until his death in 1882. See citations to footnote 1. [33] Geake, A History of the Narragansett Tribe, 97.