Rhode Island political history has been characterized by passion and turbulence. One reason for this volatility is the importance of ethnic and religious factors as determinants of voting behavior.

Until the fourth decade of the nineteenth century, Rhode Island was a homogeneous state whose population was overwhelmingly of English stock. In the 1830s, however, the situation changed. The influx of Irish Catholics produced a reaction known as political nativism, a systematic attempt by native Americans to exclude naturalized citizens from participation in the political process.

One of the principal issues of the famous Dorr Rebellion—an upheaval that produced our present state constitution—was the issue of whether or not to confer the vote on naturalized citizens, most of whom were Irish Catholics. It was decided by the conservative leaders who defeated the Dorrites to impose a real estate requirement for voting and office holding upon the foreign born, while allowing native-born citizens without property to vote merely by paying a one-dollar registry tax. This discriminatory double standard endured until the ratification of the Bourn Amendment in 1888. From the time of the Dorr Rebellion until the decade of the 1880s, the real estate requirement imposed upon the foreign-born was a source of great political agitation. First the Whig party during the 1840s, and then the Republican Party (established in 1854), fought to maintain the real estate requirement. Led by such reformers as Thomas Wilson Dorr, Henry J. Duff, Philip Allen, and Charles E. Gorman, the urban wing of the Democratic Party campaigned unsuccessfully for its abolition.

By the decade of the 1880s, the real estate requirement was becoming increasingly less effective as a measure to disfranchise Rhode Islanders of Irish stock. The state census of 1885 revealed that two out of every three Rhode Island Irishmen were native-born and therefore exempt from the real estate requirement. These native-born Irish were swelling the ranks of the Democratic Party, a political organization that had been the minority faction since 1854.

Republican political leaders under the direction of Charles R. (Boss) Brayton analyzed Rhode Island’s political status in the wake of that revealing 1885 census—a compilation that also showed the increasing numerical presence of recent immigrants from French Canada, British Canada, England, and Sweden. Of these newer arrivals, the French Canadians were by far the most significant numerically.

Brayton and his associates knew that Protestant immigrants from England, British Canada, and Sweden could be counted upon to join their Yankee cousins in the ranks of the Republican party once they were granted the vote. Brayton also felt that the Catholic French could be won over to the GOP as a result of their economic community of interest with the Yankee Republican mill owners who employed them. Further, the perceptive Brayton had detected an increasing antagonism between Rhode Island’s Irish and their coreligionists from Quebec. The Irish resented the French Canadians as economic rivals who were willing to work for lower pay and derisively dubbed them “the Chinese of the East.” They also resented French encroachment into their traditional neighborhoods in the Blackstone and Pawtuxet Valleys. The French Canadians, in turn, chafed at Irish control of the local Catholic Church and the lack of Irish sympathy for the preservation of Franco-American cultural traditions, language, and religious observances.

The Republicans, showing much more sagacity than the Democratic Irish, exploited these economic and ethno-cultural rivalries, and they courted and won the political allegiance of the Franco-American community. Before accomplishing this feat, however, they had to deal with a major stumbling block—the real estate requirement imposed by the state constitution upon naturalized citizens. The Bourn Amendment (Article of Amendment VII to the Rhode Island Constitution) was drafted and supported by Republican Party leaders. When it became law in 1888, it allowed thousands of formerly voteless Franco-American citizens to participate in the political process. It also immediately enfranchised naturalized immigrants from England, British Canada, and Sweden, all of whom opposed Irish Catholic Democrats primarily on religious grounds.

Rather than a genuine reform, the Bourn Amendment was a political masterstroke that blunted the rising threat of the Irish-led Democratic Party and preserved Republican political ascendancy in Rhode Island for another half century. Under the lead of the, astute Boss Brayton, the GOP had won the initial game of ethnic politics: they had forged a dominant Republican coalition by successfully appealing to the religious, ethnic, economic, and cultural interests of Rhode Island’s newer immigrant groups.

As some historians have noted, Irish Catholic Democrats and Yankee Protestant Republicans battled during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for the allegiance of the state’s remaining ethnic groups. Political dominance went to that party which successfully wooed the newer ethnics. In this political courtship the most desired ethnic group was the Franco-Americans, both because of its numerical size and because of its tendency to support en masse one political party or the other. It was French allegiance to the Republican Party in the period from the Bourn Amendment to the Great Depression that, more than any other factor, accounted for GOP ascendancy during that era. As Father Austin Dowling, first historian of the Diocese of Providence, observed in 1899, “The French Canadian … votes the Republican ticket. It is his vote which keeps Rhode Island Republican.”

Yankees were well aware of the importance to the GOP of the Franco-American vote. The Republicans therefore gave very early sponsorship to French politicians and elevated two of them, Aram Pothier and Emery San South, to the governorship and another,. Felix Hebert, to the prestigious office of United States Senator. The rise of the French Canadian in Rhode Island politics was in fact, more rapid than that of the Irish, thanks to the French connection with the dominant Republicans. Although substantial Irish migration began in the mid-1820s, the first Irish (and the first Catholic) state legislator, Representative Charles E. Gorman of North Providence, a lawyer and constitutional reformer, was not elected to the General Assembly until 1870; the first Irish (and the first Catholic) general officer, Secretary of State Edwin D. McGuiness, was not chosen until 1887; the first Irish (and first Catholic) governor, James H. Higgins, was not elected until 1906, and only then because of a defection from Republican ranks produced by the formation of the reform-oriented Lincoln party.

Although they arrived here in substantial numbers four decades after the Irish, the French claimed their first seat in the General Assembly in 1887, their first mayoralty (Woonsocket) in 1894, their first general state office in 1897, and their first governorship in 1909. One man—the able, articulate, and popular Aram J. Pothier—accounted for all these firsts. That the Republican Pothier immediately succeeded Governor James Higgins did little to improve relations between the Irish and the Franco-American communities.

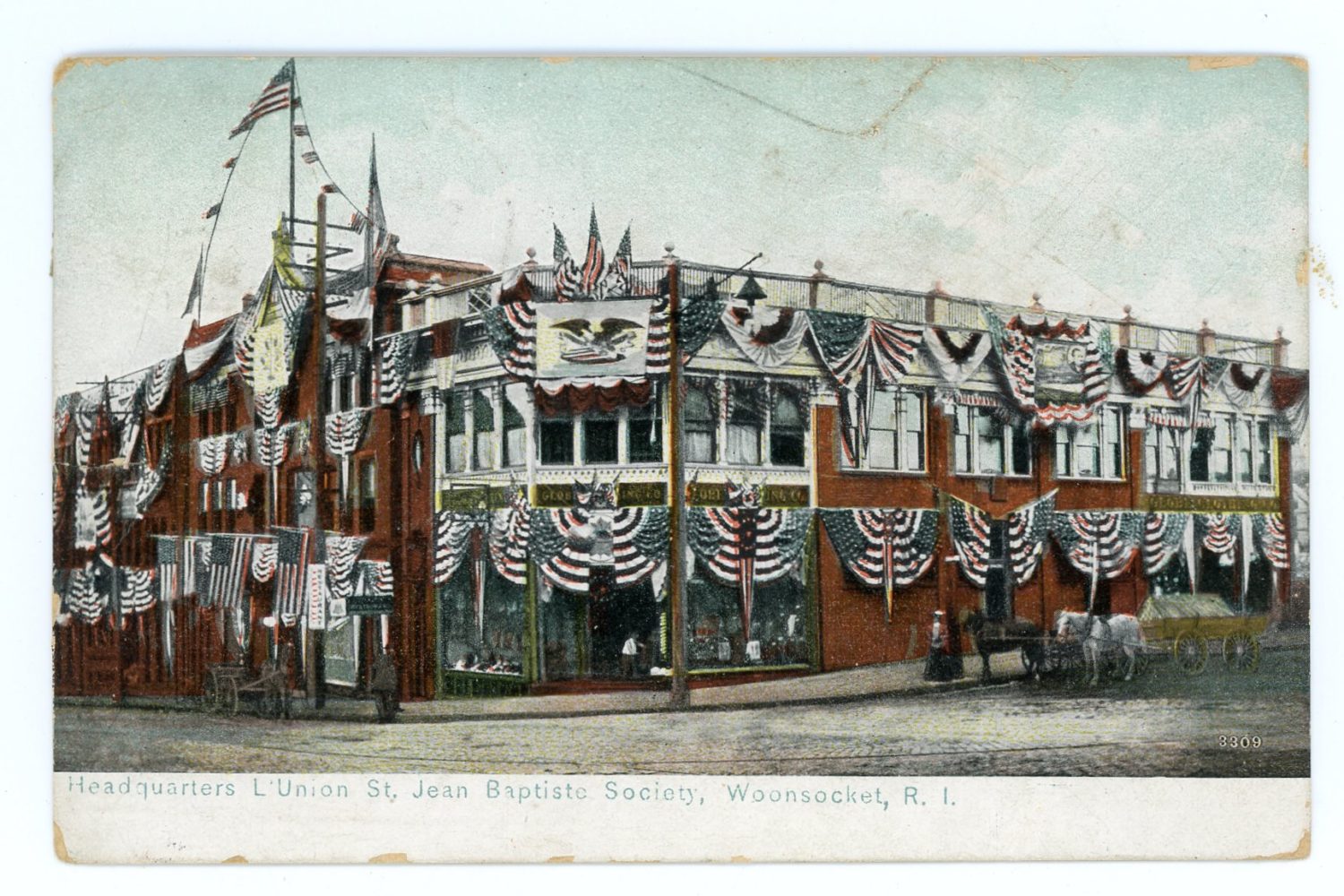

The headquarters in Woonsocket for L’Union St. Jean Baptiste d’Amerique, a fraternal society composed exclusively of French-speaking former Canadians residing in the U.S. Founded in 1900, it was called the largest and most influential French society in the country in a 1915 article (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

As historian John D. Buenker has shown, during the early part of the twentieth century the Irish Democratic minority in the General Assembly championed social reforms, consumer protection bills, pro-labor legislation, and culturally pluralistic programs that appealed to Franco-Americans, Italian Americans, and other new immigrant groups. These legislative efforts made the Democratic Party attractive to certain Franco-American leaders. Further, Irish Democratic politicians, taking a cue from the departed Boss Brayton and his Republican successors, began to advance French Canadians to elective office and high positions within their party’s hierarchy.

The most important of these early Franco-American Democrats was the articulate author and businessman Alberic A. Archambault of West Warwick, the political protégé of the Pawtuxet Valley Democratic boss Patrick Henry Quinn. In 1918 Archambault made an impressive bid for governor, becoming the first Franco-American Democrat to vie for that lofty office. As a reward for his respectable but ultimately unsuccessful effort, he was elevated by the Irish chieftains to the chairmanship of the state Democratic Party in 1919.

Another pioneer responsible for the transformation of the Franco-American vote from the Republican to the Democratic Party was the intense and volatile Felix Toupin of Woonsocket. Toupin’s rapid rise in Democratic circles coincided with several Republican blunders in 1922, blunders that dramatically weakened the GOP’s hold on the French vote.

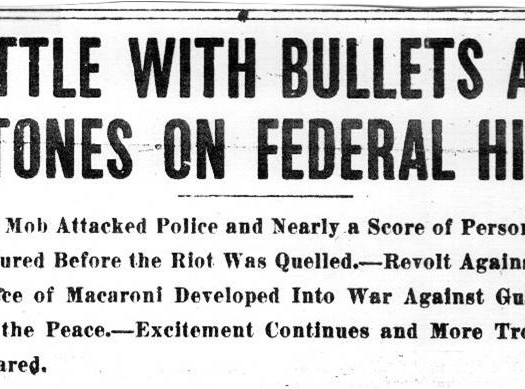

In 1920 the Republicans successfully ran a Franco-American (Emery San Souci) for governor. Widespread disillusionment with the administration of President Woodrow Wilson gave the Republicans landslide victories at every level. In the immediate wake of the 1920 state elections, the position of the GOP seemed impregnable. During San Souci’s term, however, textile mill owners dramatically cut the wages of their workers to combat the effects of a severe postwar recession. A 22.5 percent cut was accepted in 1921, but the workers rebelled when the owners attempted another cut of 20 percent in 1922 and raised the work week for women and children in their factories from forty-eight to fifty-four hours.

When a major strike erupted in January 1922, Governor San Souci, at the urging of Republican leaders (many of whom had financial interests in the textile industry), called out the National Guard. The nine-month strike was marked by sporadic violence, which included several injuries and a death. Because the mill owners used labor injunctions, evictions, and other devices in their unsuccessful attempt to break the strike, this episode severely strained the Franco-Americans’ economic bond with their Yankee employers. In the midst of this controversy, Irish Democratic leaders sponsored legislation to reduce the maximum hours of work for women and children in industry from fifty-four to forty-eight hours per week. This reform measure, which had the support of the Franco-American work force, was killed by the Republican-dominated Senate.

In 1922 it seemed that the Republicans were manifesting a political death wish, for in addition to their economic insensitivity to the plight of the Franco-American worker, they showed a cultural insensitivity to the preservation of the Franco-American’s language. Caught up in the spirit of Americanism that swept the country during the intolerant decade of the 1920s, Republican National Committeeman Frederick Peck sponsored an education act that stirred French resentment. In its most controversial provision, the Peck Act of 1922 required all instruction in private schools (except for classes in religion and language) to be conducted in English. The act’s novelty was that it provided for state supervision and enforcement. A similar English requirement had been on the statute books since 1893, but it placed control of instruction in the hands of local politicians who, in places like Central Falls and Woonsocket, ignored it. French Canadian reaction to the Peck Act was vehement, prompting one national periodical to call the outcry “the Gallic War in Rhode Island.”

The French got their revenge in the 1922 state elections, when the minority Democrats made the greatest comeback since Lazarus. Democrats nominated South Providence Irishman William S. Flynn for governor and Felix Toupin as his running mate. By exploiting the Republican use of the National Guard in the textile strike, GOP opposition to the forty-eight-hour bill, and Republican sponsorship of the Peck Act, the Democrats gained a sufficient percentage of the Franco-American vote to win the governorship, the lieutenant governorship, and control of the House of Representatives. The Republicans narrowly retained control of the rural-based and malapportioned Senate, but Felix Toupin, as lieutenant governor, would preside over the upper chamber.

The Democrats used their newfound power to push for political reform, especially the call of a constitutional convention, the reapportionment of the Senate, and the removal of the real estate requirement for voting in council elections—a device that prevented the new immigrants from vying for control of the cities in which they resided. Although Democratic reform efforts failed with the collapse of the infamous 1924 filibuster, they had made significant inroads upon the Franco-American vote.

The Republicans, sensing the erosion of French Canadian support, recalled the popular Aram Pothier from retirement to run against Toupin in the gubernatorial battle of 1924. Partly because of Toupin’s tumultuous conduct during the legislative filibuster, Pothier was victorious. He was reelected in 1926 and died in office in 1928, having served longer in the position of governor than any other Rhode Island chief executive of the twentieth century.

During the late 1920s, after the death of Pothier, the Franco-American vote gradually yet emphatically continued its move into the Democratic column. Many factors influenced this important trend: (1) the textile industry experienced a drastic decline from 1923 onward, creating high unemployment in the Franco-American community and dissolving the economic bond between the French and their Yankee Republican employers; (2) Irish Democrats continued to woo the Franco-Americans by sponsoring working-class legislation and advancing Franco-Americans to prominent positions in the Democratic Party; (3) the shift in national Democratic leadership from William Jennings Bryan’s agrarian wing to an urban ethnic base made the party more attractive to blue-collar workers; (4) the presidential candidacy of Catholic Democrat Al Smith brought Catholic ethnics into the Democratic fold; (5) the failure of the Republicans to deal effectively with the Great Depression caused disillusionment with the GOP, especially among the unemployed; and (6) the social programs, labor legislation, and pro-ethnic attitude of the federal government under the New Deal cemented the allegiance of French Canadians and other new ethnics to the Democratic party.

Aram Pothier. Born in Quebec Province, after graduating college he joined his family in Woonsocket. As a Republican, he won single terms in elections for state governor from 1908 to 1911, and became the first governor to win election to a two-year term in 1912. He was drafted by the Republican Party to run for governor again in 1924, winning that election and then reelection in 1926, when he died in office (RI State House)

One obstacle to the transition of the Franco-American vote from the Republican to the Democratic column was the eruption of the long-simmering Sentinellist controversy, a clash between the Irish-led Roman Catholic hierarchy under Bishop William Hickey and Franco-American dissidents led by Elphege Daigneault of Woonsocket and the Reverend Hormidas Beland of Central Falls. At issue was local versus centralized control within the Catholic Church. After much passion and rancor, cooler heads and Bishop Hickey (they were not one and the same) prevailed. This dispute, which might be called the darkness just before the dawn in French-Irish cultural relations, began to subside in 1928 with the excommunication of Daigneault and evaporated by 1933 with the death of the autocratic bishop and the appointment of a conciliatory successor, Francis P. Keough.

Aram Pothier. When not serving in political office, he served as President of the Woonsocket Institute for Savings and the Providence Union Trust Company. While representing Rhode Island at the Paris Exhibitions of 1889 and 1900, he persuaded several French textile firms to relocate to Woonsocket and other towns in Rhode Island.

In the fateful 1932 state election, the Franco-American vote lined up behind Democrat Theodore Francis Green and insured his gubernatorial victory. In that year the Democratic slate of general officers indicated that the party had finally mastered the game of ethnic politics. In addition to Green, a Yankee patrician, it included Irish Lieutenant Governor Robert E. Quinn; Secretary of State Louis W. Cappelli, the first Italian American to hold general office in Rhode Island; Irish Attorney General John P. Hartigan; and Franco-American cultural leader Antonio Prince as general treasurer.

Felix Hebert. Born in Quebec Province, he and his parents moved to Coventry and he went to school in West Warwick. As a Republican, he defeated Democrat Peter Gerry for a U.S. Senate seat in 1928, only to lose his reelection bid to Gerry in the Democratic sweep of 1934 (Library of Congress)

The 1934 U.S. senatorial election showed the extent of Franco-American conversion to the Democratic party. Incumbent senator Felix Hebert, a distinguished Franco-American from the Pawtuxet Valley, ran for reelection. His opponent was Yankee Democrat Peter Gerry. The Woonsocket vote tells the story. Gerry beat the incumbent Franco-American senator in that city by a vote of 10,056 to 4,870—a more than 2-to-I margin. As this election dramatically revealed, the Franco-Americans had formed a political coalition with the Irish and Italians, one that generally endured and continues to dominate the politics of Rhode Island to the present day.

[Banner: The headquarters in Woonsocket for L’Union St. Jean Baptiste d’Amerique, a fraternal society composed exclusively of French-speaking Catholics residing in the U.S. Founded in 1900, it was called the largest and most influential French society in the country in a 1915 article (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)]

This article by Patrick T. Conley was previously published in serval publications, including in Patrick T. Conley, Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection: Public Addresses and Essays (East Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2002).