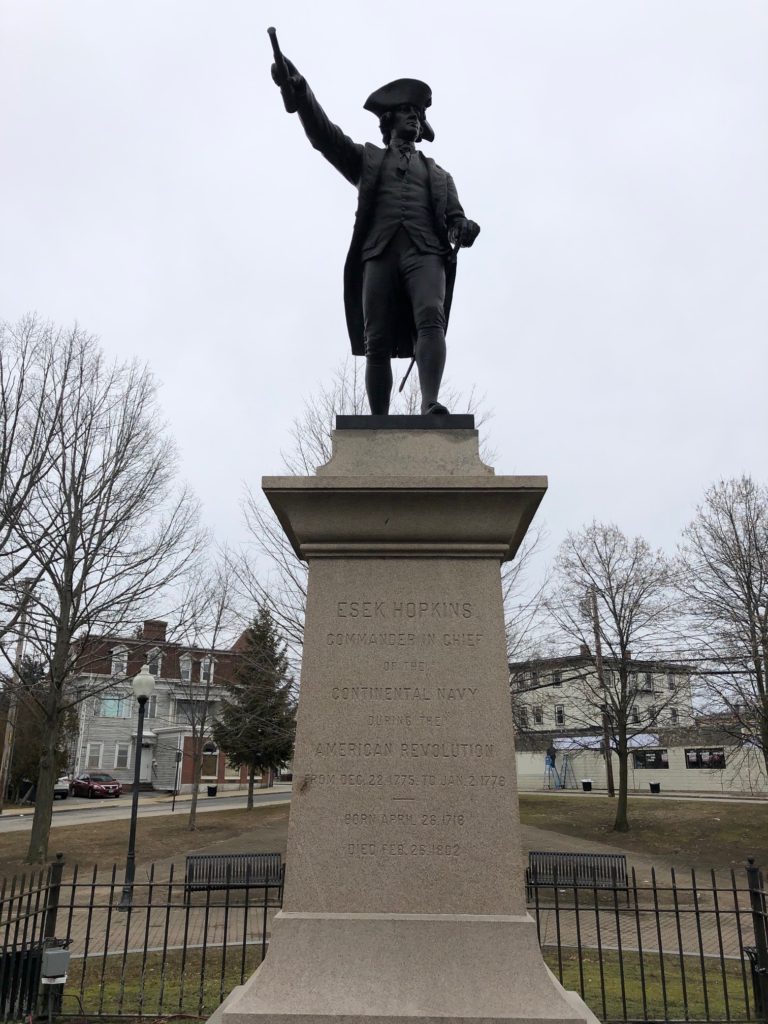

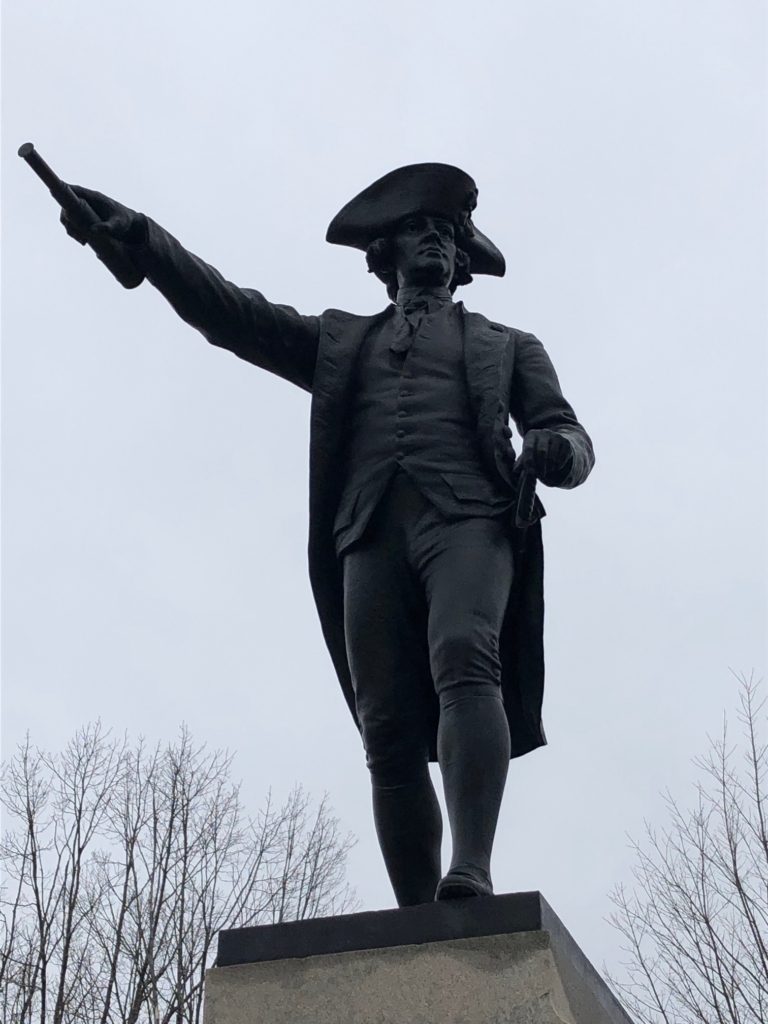

Esek Hopkins, the commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War, hailed from Rhode Island. He has two significant honorifics in Rhode Island. First, there is a statue of him in Providence located at the intersection of Branch Avenue and Charles Street, now called Hopkins Square. The attractive, heroic-style statue was erected in 1891 after being created by Theodora Alice Ruggles Kitson. Second, Hopkins has a middle school named after him in Providence.

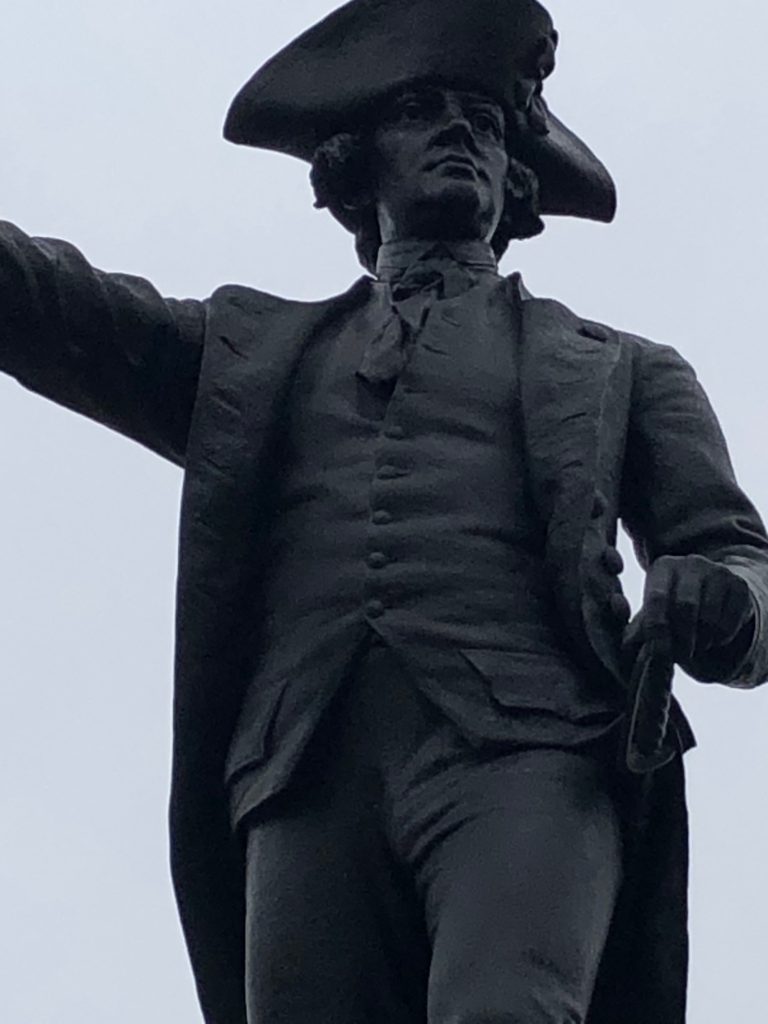

Statue of Esek Hopkins in Providence at the intersection of Branch Avenue and Charles Street, in what is called Hopkins Square (Christian McBurney)

The heroic-style statue, erected in 1891 after being created by Theodora Alice Ruggles Kitson, is attractive (Christian McBurney)

The inscription on the marble stand of the statue reads: “ESEK HOPKINS, COMMANDER IN CHIEF, of the CONTINENTAL NAVY during the AMERICAN REVOLUTION, Dec. 22, 1775 to Jan. 2, 1778. Born April 26, 1718, Died Feb. 28, 1802

In June 2020, the Providence School Board voted to remove Hopkins’s name from Esek Hopkins Middle School, citing Hopkins’s slave trading past. A proposal has been made to the Providence City Council both to change the middle school’s name and to remove the statue, for the same reason. This article is a proposal on how to address this and similar questions.

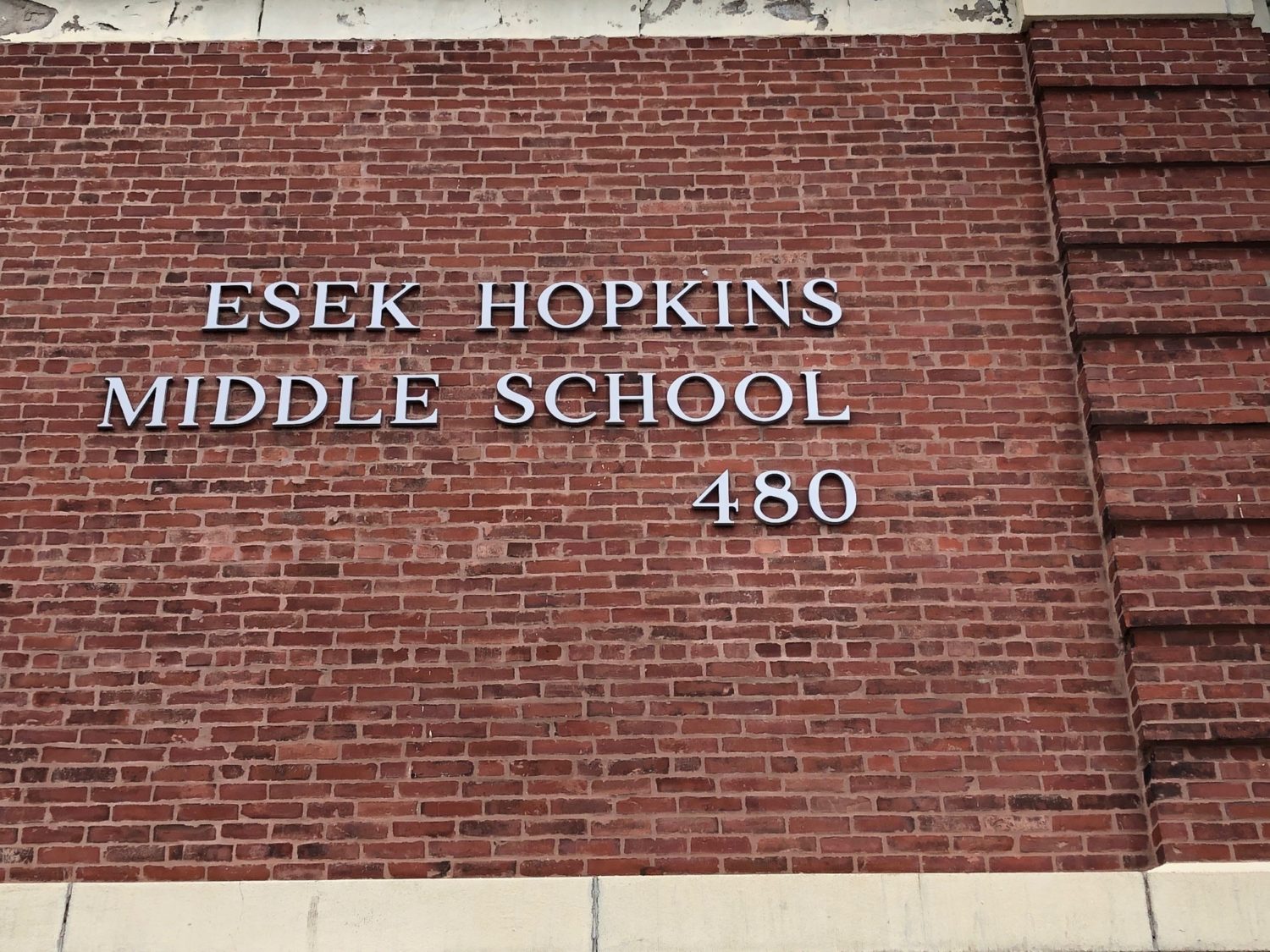

Close-up of the current signage of Esek Hopkins Middle School as it appears today (Christian McBurney)

Photo of the side of the middle school with the Esek Hopkins Middle School signage on it today (Christian McBurney)

Factors to be Weighed

Every important decision should be based on a weighing of factors. The issue raised here is no exception.

It is usually inappropriate (and often futile) to take extreme positions on any side and then to insist that one’s side is correct. I do not believe that all or most of our country’s history should be disparaged, and nor do I believe that the negative aspects should be overlooked. I believe there should be a middle ground.

Here are the relevant factors that I believe should be weighed in determining whether to remove a statue or other public honor for a historical figure and which can be applied in the Esek Hopkins case.

First, it must be recognized that as we learn more about the unpleasant aspects of persons who have been held up as heroes, those aspects can today offend segments of our population. Of course, the most profound stain on America’s history is slavery. Throughout our nation’s history, Black people have suffered from discrimination. Even after the end of slavery, Jim Crow laws imposed a harsh regime of discrimination on Blacks living in the South from the late 19th century to the 1960s. Less formal discrimination also pervaded many parts of the North and West. Today, people of color throughout the country continue to suffer from disproportionate arrest, incarceration, and police violence.

While other immigrant groups and Native Americans have experienced discrimination in our country, none has suffered the same level of discrimination as the descendants of Black slaves have. For example, second-generation Hispanics, although sometimes the object of discrimination, usually have a different outlook, given that their parents voluntarily entered the U.S. to seek a better life. And recent African immigrants, in contrast to the descendants of African captives who were forced across the Atlantic Ocean against their will and in bondage, voluntarily came to the U.S. and have been among the most economically successful immigrants in recent decades. On the other hand, it can be argued that if one group is offended by particular conduct, all groups should be offended.

Second, where a statue or building is located matters a lot. If individuals are forced to confront a statue or building that justifiably offends them on a daily basis, that is a matter of deep concern to their community. Also the statue or building may be in a neighborhood whose demography has changed over the years. By contrast, if the statue or building is in an obscure, unfrequented place, that is of less concern. Relevant to the Hopkins dispute, Black people have been about eleven to thirteen percent of our nation’s population. In some states, the percentage is more or less, while in many cities, the percentage is much greater.

Third, the original motivation for erecting the statue or bestowing the honorific is relevant. For example, many of the numerous statues of Robert E. Lee in the South were erected to support Jim Crow laws against Blacks, and thus were less intended to commemorate a war hero than to promote a political agenda that was offensive to a large portion of the population.

It is also appropriate to inquire about the motivation of those who are advocating for the removal of a statute or honorific in order to ascertain whether such advocacy is truly based upon concerns for historical accuracy and the feelings of members of the community. While the honors bestowed in the past should be subject to periodic review, they should not become captives of contemporary political or social disagreements.

Fourth, it matters if the statue or building is owned by the federal government, state government, or local government or other local institution. If the statue or building is owned by the federal government, then the considerations of the nation as a whole must be taken into account. However, if the statue or building is under the jurisdiction of a locality, then local concerns must predominate.

Fifth, it is important not to impose today’s moral and social standards in evaluating the life of a past leader. Among historians, this is called presentism. An individual should be judged primarily based on the norms of the individual’s times. It is not appropriate, for example, to criticize a historical figure from the eighteenth century for not believing that gay people should have the same political and social rights as straight people. Such a concept was entirely foreign to the culture of those times and it would be profoundly unfair to judge an individual who lived hundreds of years ago primarily by the morality of our times.

On the other hand, when dealing with statues and honorifics that exist today, not acting with some degree of presentism is going too far. It must be recognized that a statue is viewed or a building is used today in our own time. Thus, the statue or name may impact our daily lives. What is socially acceptable has changed over time. It is therefore appropriate to give some weight to the standards of today in evaluating the merits of honoring a figure from times past.

Sixth, in order to apply the approach of placing the historic figure in proper context, the figure’s contribution to history and progress should be given the greatest weight. The figure may have made certain personal or business choices that, by today’s standards, are offensive. But at the same time, the individual may have played an important role in advancing human progress for thousands and perhaps millions of people. It is appropriate to give great weight to one who has bettered the lives of many or altered the course of history for the good, even if certain aspects of the person’s individual conduct or views are offensive when viewed through the prism of today’s standards. It is as a result of accomplishments in the person’s own time that we consider an individual worthy of praise. The person’s accomplishments in the context of his or her time, often at great personal risk or sacrifice, form the measure of the individual’s worthiness of being honored.

Let’s take George Washington as a quintessential example. Should the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., constructed in his honor, be stripped of his name? Should the name of our nation’s capital also be changed?

Washington was a slaveholder. He kept hundreds of enslaved persons in his lifetime, exploiting them for his personal benefit and preventing them from enjoying freedom. Even though that was entirely legal in his home state of Virginia, by every current standard of morality such behavior is offensive. On the marginally positive side, Washington was the only substantial slaveholder among the Founders to free his enslaved persons (he did it in his will).

Significantly, the Washington Monument is owned by the federal government. Located in our nation’s capital, it sits on federal land in relatively open parkland space. Washington, D.C. itself is our nation’s capital. Accordingly, the interests of the entire nation are at stake, not just those of the citizens of Washington, D.C.

Furthermore, evaluating Washington solely on the basis of his slaveholding is inappropriate. Doing so would simply impose our modern standards on a figure who accomplished extraordinarily important achievements unrelated to his slaveholding.

As an extreme example, this past summer a history professor at a New York City university published an opinion piece harshly chastising Washington for among other transgressions failing to recognize the rights of women and gay or transgender persons. This is the height of absurdity. Almost no one living in Washington’s time, anywhere in the United States or the world, supported women’s rights that we recognize today. And that is even more the case when it comes to the rights of gay or transgender people. Judging an individual who lived more than two hundred years ago primarily by the rapidly evolving mores of today is inappropriate and does a disservice to our history.

Our nation cannot throw away all of our history on the grounds that the historical figures failed to follow modern political, social and cultural norms. That would result in a loss of understanding of our country’s history and the remarkable achievements of those individuals who created the institutions that continue to benefit us. It would also be unfair to the reputations of the historic figures.

Instead, we should ask, how much did the person contribute to human progress and the development of our country in their own times? Did the individual make an outstanding contribution to society in his or her own time? And does the contribution substantially outweigh what we view today as their personal transgressions?

Returning to Washington’s case, we must recall that he was the towering figure who led the new United States in its successful war of independence against Great Britain, the American Revolutionary War. The founding events of one’s country are important foundational pillars for any country. And the American Revolution definitely represented a huge step in human progress. At the time, almost all countries in the world were ruled by monarchs supported by aristocratic elites. In this world, rank was determined by birth. Thomas Jefferson elucidated the simple foundation of the United States in the Declaration of Independence in 1776—that all men are created equal. This was a remarkably revolutionary concept for the times. Every man was, in theory, equal to every other. At the founding of the United States, this helped lead to a republican and democratic form of national government that has survived and prospered to this day, almost 250 years later. Of course, back then, the term “all men” meant white men who owned property. It then excluded Black people, Native Americans, women and landless white men. It has been a long, painful process for our nation, including a bloody Civil War, but the political theories propounded by the Founders, despite their own failures to adhere to them, set the stage for each of those groups to eventually achieve equality under the law. Our country is still trying to achieve the ideal.

The United States does not have a homogenous population, unlike some other countries. We have an incredibly diverse population, even among white European descendants. Our country is held together by the national creed of freedom and liberty introduced by our Founders during the American Revolution. If we as a people cannot believe in that, then we will have not one history, but many segmented histories.

Also not appreciated today is that the American Revolution represented great progress for the cause of abolishing slavery and the African slave trade. I recently argued this point focusing on the African slave trade in a three-part article in the online Journal of the America Revolution.[1] (Great Britain at the time of the American Revolution was the world’s greatest slave trading nation and prevented attempts by American colonies to limit it.) Many Founders were not unmindful that in demanding freedom and liberty from Great Britain, enslaved persons lived in their midst who were denied that freedom and liberty. Prior to the American Revolution, no society in the Western world had had a national abolitionist movement. The American Revolution was perhaps the first national abolitionist movement in world history and set the stage for others to come. When the dust settled, each state in the North had taken steps to end slavery, and a fixed date had been established for ending legal American participation in the African slave trade. Tragically, this progress did not extend to the states from Virginia to the south, even if many Founders such as Jefferson had mistakenly expected the institution of slavery to die out of its own accord. Nonetheless, the American Revolution undoubtedly represented progress for the antislavery movement, and the individuals who led that movement, for all their personal failings, made significant contributions to the end of the institution of slavery and the African slave trade.

All those who struggled to achieve independence from Great Britain risked his or her life for an ideal greater than the individual’s own life. If the war of independence had been lost, its leaders faced hanging, imprisonment, and/or other punishments. George Washington, of course, was the indispensable man of the American Revolution. As a result of his leadership, independence was gained and republican and democratic government was made possible. His contributions to the cause of American independence and democratic governance have bettered the lives of millions who have come after him.

Washington served as the first president of the United States, making important contributions by following the U.S. Constitution and not trying to dominate all three branches of government despite his own huge popularity. Moreover, Washington voluntarily gave up power twice—once as the commanding general of the Continental Army, and later after the second term of his presidency ended. This voluntary relinquishment of power set the stage for the peaceful transition of authority in the United States, establishing it as the most stable government in the history of the Western World. In Great Britain, King George III said that Washington, by stepping down as President, became “the greatest character of the age.”[2]

Washington’s contributions to our country and its political institutions have been massive. In addition, the Washington Monument is a federal monument on federal park land. These factors substantially outweigh his personal slaveholding past.

Whatever shortcomings permeated Washington’s personal life, his contributions to our civic life have been extraordinarily positive. Honoring George Washington’s does not honor his failings, it acknowledges and memorializes his remarkable achievements. In addition, the Washington Monument is a federal monument on federal park land, and Washington, D.C. is the capital of our nation. These factors substantially outweigh Washington’s personal slaveholding past.

Esek Hopkins’s Slave Trading and Slaveholding Past

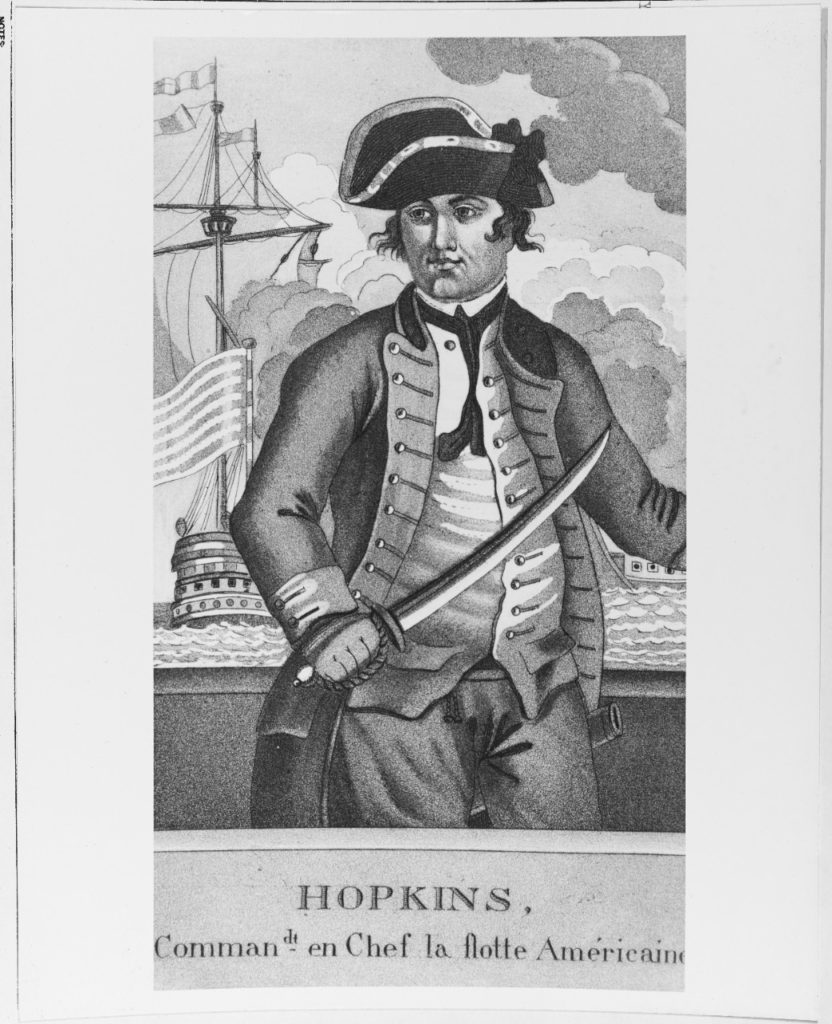

Drawing of Esek Hopkins taken from a British printer by a French newspaper (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Now let’s turn to Esek Hopkins. Hopkins’s reputation is deeply tainted. In 1764 and 1765 he commanded a ship that on a slave trading voyage to Africa and back. Even then, participating in the slave trade was viewed with disfavor by many. It was legal and had been for centuries. Indeed, it was encouraged by America’s mother country, Great Britain.

Today, the idea that a slave trade ever existed is deeply disturbing. The concept of sailing a ship to Africa, buying captives on the coast from local tribes, and transporting them in brutal, overcrowded conditions below decks, and then selling the captives to white planters in the Caribbean and the American South for a lifetime of enslavement is appalling. The transatlantic African slave trade is one of the greatest human tragedies in world history.

The particulars of Esek Hopkins’s slave voyage are especially ugly. He commanded the slave ship Sally in a voyage in which the Brown brothers, famous Providence merchants, were the investors. Inexperienced at negotiating purchases of captives with local chieftains and European whites, Hopkins spent a great amount of time on the African coast. As a result, the captives he acquired lay in misery in the hot holds of his ship for months. Of the 196 Africans he purchased, at least 109 perished. Most captives expired on the voyage home, in the dreaded Middle Passage, from disease. A number of the suffering captives on board courageously staged an insurrection and tried to overwhelm Hopkins and his crew. The rebellion was brutally repressed, with eight of the captives shot and killed and more wounded. Afterwards, several captives committed suicide, jumping overboard into the sea. Hopkins’s voyage finally ended in British-controlled Barbados, where the surviving captives, most emaciated from disease and poor food, were sold into a lifetime of enslavement.[3]

Esek Hopkins did not make another African slave voyage. Still, he had commanded one, and its results were disastrous.

Esek Hopkins was also a slaveholder. His crew that sailed Sally included a “Negro boy,” Edward Abbey, Hopkins’s personal enslaved child.[4] In a 1774 census of the colony of Rhode Island, Hopkins is shown as having four Black persons living at his household in what was then North Providence.[5] The census does not indicate if all four were enslaved, but they likely were, given Hopkins’s background.

Another stain on Hopkins’s reputation arose when he served as commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy. Hopkins led a small flotilla of Continental Navy warships in the fall of 1776. They came across a Royal Navy bomb brig, Bolton, and captured it and its small crew.[6] The British vessel’s crew included seven Black men. They had either enlisted from Rhode Island to serve on the British vessel, or had been forced to serve by their white masters. At least three of them had been enslaved by Joseph Wanton, former governor of Rhode Island, and one had been enslaved by Francis Brinley.[7] Both Wanton and Brinley were Newport Loyalists, who supported King George III. The captured Black men were treated as property and not as human beings who were prisoners deserving of rights. Hopkins carried them to Providence where the “Seven Negro Slaves” were sold as prizes of war under the auspices of Rhode Island’s Admiralty Court. [8] Hopkins purchased one of the Black captives, Dragon Wanton.[9]

A 1777 military census of Rhode Island adult males indicated that Hopkins had “two Negroes,”[10] both likely enslaved persons. The Rhode Island 1790 federal census listed Hopkins, but no enslaved persons were reported as residing in his household.[11]

Esek Hopkins’s Service in the Revolutionary War

What of Esek Hopkins’s role as a leader in the American Revolutionary War? Is it possible his service outweighs his negative factors? Hopkins’s service overall was hardly a success.

Early in the war, Hopkins had an important advantage. His elder brother, Stephen Hopkins, was a ten-time governor of Rhode Island and its most important politician. Stephen Hopkins served as a delegate from Rhode Island in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and would sign the Declaration of Independence.

In Philadelphia, Congress began organizing a national military force, including the Continental Navy. Stephen Hopkins served as chair of Congress’s Naval Committee, which had other New Englanders as members. Not surprisingly, Esek Hopkins was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy, on December 22, 1775.[12] Hopkins’s appointment was apparently more due to nepotism and political connections than merit.

On paper Hopkin’s new command was equivalent to George Washington’s rank as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, but Congress never treated him as such. The reality was that the Continental Navy never had sufficient ships and was no match for the Royal Navy, then the world’s largest naval force.

In mid-February 1776, Hopkins was ready to sail with a modest squadron of Continental Navy ships. Congress’s Naval Committee ordered him to cruise to the Chesapeake Bay and along the shores of the southern colonies in order to “search out and attack , take or destroy all the naval force of our enemies that you may find there,” a tall order indeed.[13] To most delegates, this meant going after Lord Dunmore, the former Royal governor of Virginia who was using a small British naval force to attack the Virginia coast and had enraged Virginia slave owners by freeing Virginia enslaved persons who enlisted in his force.[14]

Hopkins decided instead to head directly to Nassau on the British-controlled island of New Providence in the Bahamas. Hopkins’s bold amphibious attack on Nassau was a success, as he seized and carried back in his ships desperately needed cannon, gunpowder, and military stores.[15] This was the high water mark for Hopkins’s service, even though southern delegates in Congress resented that he had not protected their coastline, including on his return voyage.

Off the coast of Block Island, Rhode Island, Hopkins’s small squadron came across some small British warships. They were able to capture the bomb brig Bolton and schooner Hawk.[16] On April 6, four of Hopkins’s largest warships came across the twenty-gun HMS Glasgow. Although the British ship was outgunned, Hopkins attacked it by sending in only one ship at a time. Glasgow fought off each attacker and was able to escape from practically the entire Continental Navy, causing Hopkins to be criticized.[17]

In August 1776, Congress called Esek Hopkins to account for his conduct, and as well as for criticism received from his own officers, including for failing to follow Congress’s orders in several instances. Hopkins, in turn, blamed all of his officers, save his own son, a ship captain. Hopkins antagonized delegates with his truculent attitude. John Adams, who stood by Hopkins, detected anti-New England feeling during the debates. Still, on August 16 Congress voted to censure Esek Hopkins for failing to follow orders to protect the southern coastline.[18]

Hopkins returned to Providence, Rhode Island, where he had command of three Continental Navy frigates and a sloop. In early December 1776, Hopkins was informed that a large and powerful British naval force was headed towards Narragansett Bay. He had ample opportunity to order his crews to sail his ships to a safe port, such as Boston, but he failed to do so, despite pleas from the Rhode Island governor. Hopkins selfishly wanted to keep his ships at Providence to protect the city from a potential raid. He put his parochial desire in front of the larger interest of the country. Once the Royal Navy warships arrived in Narragansett Bay on December 8, 1776, it was too late. Hopkins’s frigates were bottled up by a blockade of Narragansett Bay and would not try to escape until 1778.[19]

Early in the morning of January 2, 1777, the 32-gun British frigate Diamond ran aground near Warwick Neck in the northern part of Narragansett Bay. The British ship lay on a careen at low tide. Hopkins sailed over in the sloop Providence to view the situation, but he never ordered any of his warships to attack the stranded Royal Navy frigate. On land, a local artillery outfit fired a single artillery piece at Diamond, penetrating its exposed hull in a few places, but not disabling it. At high tide early the next morning, Diamond’s crew was able to free the frigate and sail it back to Newport. Hopkins properly received more criticism.[20]

Hopkins’s own officers turned against him and presented their complaints in a petition submitted directly to Congress. Ten officers from his flagship, the Continental frigate Warren then stationed in Providence, informed Congress that Hopkins had criticized delegates to Congress, ridiculed all religion, swore frequently, ordered prisoners to be put into chains (Hopkins was trying to bully them into enlisting in his crews), and was so harsh in his discipline and language that he had trouble attracting recruits to man his ships.[21] The dispute turned bitter after Hopkins had one of the officers who signed the petition court-martialed at Providence and sentenced to give up his commission.[22] On March 26, 1777, Congress suspended Hopkins from command.[23] One historian wrote, “It is a measure of Congress’ dissatisfaction with Hopkins at this time that it took this drastic step without giving him an opportunity to defend his conduct.”[24] After this development, it was hardly surprising that Congressional delegates voted to dismiss Hopkins from the Continental Navy altogether on January 2, 1778.[25] Congress’s perception of the matter is indicated in its refusal to appoint a new commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy.

Painting of the raid of New Providence in the Bahamas by Esek Hopkins and his Continental fleet of ships, with marines. A Black marine holds a musket. This successful action was the highlight of Admiral Hopkins’s service as commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Hopkins remained in Rhode Island for the remainder of the war. From December 1777 to May 1780, he served honorably on the Rhode Island Council of War, the committee that administered much of the state’s day-to-day war effort.[26] He served in the Rhode Island General Assembly until 1786 and died at his Providence farm in 1802. He is buried in historic North Burial Ground in Providence. The Esek Hopkins House at 97 Admiral Street on the north side of Providence is on the National Register of Historic Places and has been on and off the Providence Preservation Society’s Most Endangered Properties List.

Weighing of the Factors

What to make of Esek Hopkins’s service? He was a Patriot. He served the cause of American independence as a leader, placing his life and property at risk. However, his tenure as commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy was largely a failure. Apart from his bold strike on the Bahamas, he did not have any marked success, and he showed a lack of boldness and poor decision making in several other instances. He did not inspire loyalty in his officers or sailors, and in the political arena he did not deal effectively with Congress. Maritime historian William M. Fowler, Jr. wrote of Hopkins that he was “not an effective naval officer” and that he “was insensitive to the politics of the Continental Congress and did not appreciate the nature of leadership required for command at sea during the Revolution.”[27]

Accordingly, there is not much to cite in support of honoring Hopkins for his service during the Revolutionary War.

Based on his unsuccessful service and suspension a little more than a year after his appointment as commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy, it is not clear why it was decided in the 1880s to erect a statue of Esek Hopkins. It appears that Rhode Island’s Protestant English stock who supported the erection of the statue were looking for a hero of similar stock. At the time, Rhode Island’s English-heritage residents felt overwhelmed by increasing numbers of immigrants to Rhode Island, many of them Catholics from Italy, Portugal, Ireland and French Canada. Since Hopkins had the distinction of being the United States Navy’s first commander, he fit the bill, despite the shortcomings of his service.

There are major factors weighing against Esek Hopkins. His slave trading is rightly viewed as appalling today. Even back in his time, as stated, slave trading had an odor to it, despite it being legal. Hopkins was also a slaveholder.

Given this ugly history, it is insensitive to expect students, particularly Black students, to have to live with “Esek Hopkins” in the title of their middle school’s name every day. Their parents also have frequent dealings with the school. Approximately 21 percent of the 550 students at Esek Hopkins Middle School are Black (about 64 percent are Hispanic and about 7.5 percent are white).[28]

Based on a weighing of the factors, it is easy to conclude that Esek Hopkins’s name should be removed from the school that currently bears his name.

Determining to remove the statue of Esek Hopkins is not as easy a decision as changing the name of the middle school, but I believe that appropriate consideration of the various applicable factors favors removal. There is more than ample grounds for the Providence City Council to decide to remove the statue. The positive aspects of Esek Hopkins’s public career, mostly offset by the negative aspects, are not impressive. And the net positive aspects of Hopkins’s naval service do not outweigh the strongly negative factors of his having been a slave trader and slave owner. In addition, the statue is in a public space that can be seen by all members of the general public who reside in a city where the Black population is substantial and to whom Hopkins’s past is particularly odious (even if the park is not a well-trodden one). If the statue was in a historic cemetery, for example, the decision might be a harder one.

Perhaps the United States Navy would be interested in acquiring the statue, since Esek Hopkins’s greatest claim to fame was that he was the first commander of the United States Navy. The U.S. Navy has several excellent naval history museums, including one at its headquarters in Washington, D.C., one at the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, and another at the Naval War College in Newport. Even then, Navy officials may well hesitate to place the statue outdoors, given that it would likely offend Black naval officers, sailors and potential recruits. The decision as to what to ultimately do with the statue should be a secondary consideration. The priority should be its removal by reason of its failure to meet the balancing test to which public monuments and other public honors should be subjected.

I also believe it would be reasonable for the Providence City Council to leave the Esek Hopkins statue in place in Hopkins Park, where it has been for about 129 years, but to add a slave medallion or other marker that would provide a fuller history of Esek Hopkins than is engraved in the base of the statue.

[1] See Christian M. McBurney, “The First Efforts to Limit the African Slave Trade Arise in the American Revolution,” Parts I, II and III, in the online Journal of the American Revolution, at https://allthingsliberty.com (search for “African slave trade”). For the links to each of the three articles, see https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/09/the-first-efforts-to-limit-the-african-slave-trade-arise-in-the-american-revolution-part-1-of-3-the-new-england-colonies/; https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/09/the-first-efforts-to-limit-the-african-slave-trade-arise-in-the-american-revolution-part-2-of-3-the-middle-and-southern-colonies/; and https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/09/the-first-efforts-to-limit-the-african-slave-trade-arise-in-the-american-revolution-part-3-of-3-congress-bans-the-african-slave-trade/. [2] Rufus King Memorandum Book, May 3, 1797, in Charles R. King, ed., The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King, vol. 3 (G. P. Putnams Sons, 1896), 545. [3] This summary of Sally’s voyage is based primarily on the report, largely prepared by James T. Campbell, at the Brown University website. Go to http://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/report/, and then click on the Slavery and Justice report. For links to images of many of the applicable documents, see the same website and click on link Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764-1765. [4] See Brown University’s Slavery and Justice Report cited above. [5] John R. Bartlett, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 1774 (Clearfield Company Reprints, 1990) (originally published in 1858), 233. [6] Journal of the Continental Navy Brig Andrew Doria, April 5, 1776, in William Bell Clark et al., eds., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 13 volumes (Government Printing Office, 1964-2019), 4:669-70. [7] List of Prisoners Taken in the H.M. Bomb Brig Bolton, in ibid., 669-70. [8] Libel of John Cole and Commodore Esek Hopkins Against Cables, Anchors and Negro Slaves, in Providence Gazette, Sept. 14, 1776; see also List of All the Vessels and Cargoes etc. Brought into the Port of Providence and Libelled, Tried and Condemned in the Maritime Court AD 1776, in Clark, Naval Documents of the A. R. 7:642 (capture no. 19; “7 Negro Men”). [9] E. Hopkins to W. Ellery, Nov. 7, 1776, in ibid., 7:84. [10] Mildred M. Chamberlain, ed., The Rhode Island 1777 Military Census (Genealogical Publishing Co., 1985), 64. [11] First Census of the United States, 1790, Rhode Island (Government Printing Office, 1908), North Providence, 32. [12] Resolution, Dec. 22, 1775, in Worthington C. Ford, ed., The Journals of the Continental Congress, 34 volumes (Library of Congress, 1904-37), 3:443-45. [13] Orders of the Naval Committee to Esek Hopkins, Jan. 5, 1776, in Clark, Naval Documents of the A. R. 3:637-38. [14] See Lord Dunmore’s Emancipation Proclamation, Nov. 7, 1775, in ibid.; 2:920; William M. Fowler, Jr., Rebels Under Sail, The American Navy during the Revolution (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976), 61. [15] Esek Hopkins to John Hancock, April 9, 1776, in Clark, Naval Documents of the A. R. 4:735. [16] Journal of the Continental Brig Andrew Doria, April 5, 1776, in ibid., 669. [17] Esek Hopkins to John Hancock, April 9, 1776, in Clark et al., Naval Documents of the A. R. 4:735-36. [18] Censure Resolution, Aug. 16, 1776, in Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:658-59 and 660-62; Journal Entry, Aug. 12, 1776, in L. H. Butterfield, ed., The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, 4 vols. (Belknap Press, 1961), 3:405-06; Fowler, Rebels Under Sail, 241. [19] See Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign, The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Westholme, 2011), 12-14. [20] See E. Hopkins to N. Cooke, March 13, 1777, in in Clark, Naval Documents of the A. R. 8:98-99; Examination of Captain John Grannis by the Continental Marine Committee, March 24, 1777, in ibid., 189-90; Log of HMS Diamond, Jan. 2-3, 1777, in ibid., 7:853 (Diamond could only bring to bear two of its guns against the land artillery). [21] Examination of Captain John Grannis by the Continental Marine Committee, March 24, 1777, in ibid., 189-90; Officers of the Continental Frigate Warren to Robert Treat Paine, Feb. 11, 1777, in ibid., 1166-67. [22] See Court Martial of Lieutenant Richard Marvin, April 3, 1777, in ibid., 263-66. The court-martial occurred before news of Hopkins’s suspension reached Providence. Hopkins later sued the officer, Richard Marvin, and another officer, Samuel Shaw, for defamation of character. Congress paid for Marvin’s and Shaw’s attorneys’ fees, which has been described as the first “whistleblower” protection extended by Congress. Louis Arthur Norton, “The Revolutionary War Origin of the Whistleblower Law,” in the online Journal of the American Revolution, at https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/03/the-revolutionary-war-origin-of-the-whistleblower-law/. See also Allison Stanger, Whistleblowers: Honesty in America from Washington to Trump (Yale University Press, 2019), 25-30. Stanger has a fine detailed discussion of Hopkins’s travails, but she does not mention the failure of Hopkins to get this ships out of Narragansett Bay before the British arrived at Newport or the Diamond affair. [23] Resolution, March 26, 1777, in Ford, Journal of the Continental Congress 7:203-04. [24] Paul H. Smith, ed., Letters of Delegates to the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, volume 6 (Library of Congress, 1980), 490, n. 2. [25] See Resolution, Jan. 2, 1778, in Ford, Journal of the Continental Congress 10:20. [26] See John K. Robertson, Proceedings of the “Recess” Committee of the Rhode-Island General Assembly 1775-1776 and the Rhode Island Council of War 1776-1782 (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019), 445-46. [27] William M. Fowler, Jr., “Hopkins, Esek (1718-1801), in Richard L. Blanco, ed., The American Revolution, 1775-1783, An Encyclopedia, volume 1 (Garland Publishing, 1993), 775. [28] See Students at Esek Hopkins Middle School, at https://www.niche.com/k12/esek-hopkins-middle-school-providence-ri/students/ (accessed January 18, 2021).