Rhode Island has many claims to fame. It is unusual, however, to discover a new one. With “12 Years a Slave” winning the 2013 Academy Award for best picture, its protagonist, Solomon Northup, became famous (for the second time). It then became known that Solomon’s father, Mintus Northup, had been born and raised a slave in North Kingstown, Rhode Island.[1]

“12 Years a Slave” is the story of Solomon Northup, a New York State African-American man who in 1841, while a free man, was drugged and kidnapped in Washington, D.C. and then sold into slavery at an auction in New Orleans. Northup labored as a slave on plantations in the state of Louisiana for twelve years before his dramatic release. The movie is a faithful (even if painful to watch) adaptation of the 1853 slave narrative memoir authored by Northup in 1853. Northup’s memoir, an excellent read, itself became a best-selling book in 2013.

In his memoir, Solomon had only the following to say about his Rhode Island relatives:

As far back as I have been able to ascertain, my ancestors on the paternal side were slaves in Rhode Island. They belonged to a family by the name of Northup, one of whom, removing to the State of New York, settled at Hoosic, in Rensselaer County. He brought with him Mintus Northup, my father. On the death of this gentleman, which must have occurred some fifty years ago, my father became free, having been emancipated by a direction in his will.[2]

Readers may be surprised to know that in the eighteenth century, Rhode Island had the highest percentage of slaves in New England, and southern Rhode Island had the highest percentage of slaves in rural New England. North Kingstown, where Mintus Northrup was born and raised, is, of course, in South County, now known as Washington County and then called King’s County. In colonial times, in South County, a class of successful farmers rose who resided on large farms (based on New England standards) and raised dairy cows, sheep and horses, including the renowned Narragansett Pacer. Their products, especially cheese, sheep and horses, were frequently purchased by Newport merchants, who in turn shipped them to Caribbean islands, where white masters fed their slaves the imported food. Narragansett Planters, as they are sometimes called, typically owned from five to twenty slaves. (In a previous article, I wrote about Narragansett Planters, and in a previous book, I wrote about South County slavery).[3]

Because Mintus Northup, Solomon’s father, was a slave, few records of his existence were ever made, and even fewer survive. We know more about Mintus’s masters in the white Northup family of North Kingstown.

When Mintus was born in 1777, he became the property of Immanuel Northup. Immanuel’s grandfather, Stephen Northup, had arrived in Rhode Island in 1644 and had helped to settle North Kingstown.[4] Immanuel’s father, Henry Northup (born in 1663) built the family’s North Kingstown homestead in about 1690, which, according to North Kingstown historian Tim Cranston, survives to this day on Featherbed Lane on the southern side of the Annaquatucket River.[5] In 1740, the same year Henry died, he reportedly had seven slaves at his North Kingstown household.[6] Immanuel Northup, born at the homestead farm in 1699, became a respected member of the community, serving as sheriff of King’s County for most years from 1729 to 1747, an associate justice of the King’s County court on common pleas starting in 1749 and its chief in 1767, and a North Kingstown deputy to the General Assembly in 1740. He also served in the King’s County militia, rising to become colonel of a regiment in 1742.[7] Immanuel Northup and his family may have been Baptists, who had an active congregation in North Kingstown.

Rhode Island’s 1774 census indicated that Immanuel Northup resided in North Kingstown with his wife and seven blacks, who were probably all slaves.[8] Immanuel’s slaves likely included Mintus’s mother, whose identity is not known. Solomon would later describe her in his memoirs as a quadroon—three-quarters white and one-quarter black.[9] She gave birth to Mintus on or about August 31, 1776 and, as was the custom of the times, Mintus took as his last name that of his white master.[10] Immanuel’s other slaves may have included Mintus’s siblings and grandparents, but probably not his father. The coming of the Revolutionary War, starting in 1775, for various reasons began a swift decline in South County slaveholding. In a 1782 census, Immanuel is listed as having in his household one Indian (a free servant) and four blacks.[11] The four blacks probably included Mintus and his mother.

Immanuel Northup outlived three of his wives. By his second wife, Sarah Gould, he had a son, Henry, who would eventually become Mintus’s second owner. As an adult, Henry left his father’s North Kingstown farm and became a ship captain operating out of Newport. Known as “Captain Henry,” newspapers from 1772 to 1774 refer to him commanding merchant ships on several voyages to the Caribbean.[12] On December 20, 1774, at the Second Baptist Church in Newport, he married Mary Gardner, the daughter of John Holmes Gardner of Newport.[13]

During the American Revolution, Captain Henry Northup was a Loyalist—a supporter of King George III. When the British army occupied Newport in December 1776, he remained in Newport, as did many Loyalists. However, he likely found it difficult to continue his livelihood as a merchant ship captain, given the decrease in trade due to Newport’s occupation and the ongoing war. He refused to command a Loyalist privateer preying on patriot shipping. Instead, on December 1, 1777, he decided to return to North Kingstown. He received permission from British authorities to travel to the Rhode Island mainland, but when he landed, he was immediately ordered to appear before the General Assembly, then sitting at East Greenwich, out of concern that he was “unfriendly to the liberties of America.”[14] But Captain Henry must have mollified the Assemblymen, as his name does not thereafter appear in records of suspected Loyalists. He did not serve in any local militia companies either. He remained outwardly neutral and started a new life as a farmer.

Immanuel Northup died on May 28, 1790, less than a month before his ninety-first birthday.[15] At the time of his death, he had just two remaining slaves, who were granted their freedom under his will.[16] In the census of 1790, Captain Henry was listed as having five slaves in his household.[17] Thus, Immanuel must have transferred several of his other slaves to his son prior to his death. As a result, Captain Henry became the new master of twelve-year-old Mintus and perhaps his mother.

In 1784, Rhode Island enacted a law banning the enslavement of any newborn persons, but that law did not cover Mintus. While many South County masters freed their slaves in the years following the end of the Revolutionary War, viewing slavery as inconsistent with the principles of the American Revolution, Captain Henry chose not to.

Immanuel Northrup was generous to each of his sons, but that meant that none of them ended up with a large estate after his lands were divided among them. Since he was not the eldest son, Captain Henry did not receive the homestead farm. With Rhode Island’s post-war economy suffering, Captain Henry decided to do what many Rhode Island younger sons did at that time—start a new life in upstate New York. He moved his family to Hoosick Falls, a town in Rensselaer County in New York State. Captain Henry purchased a farm of several hundred acres at Hoosick Falls and built a log house overlooking a waterfall.[18] He brought his wife, Mary, the rest of his family, and Mintus with him. It is not known what happened to Mintus’s mother or other members of Mintus’s family. In 1790, a Caesar Northup headed a family of four African Americans in North Kingstown—this household may have included members of Mintus’s family.[19]

At Hoosick Falls, as a teenager, Mintus labored as a slave on Captain Henry’s farm. As Mintus grew to be a young adult, he must have agitated his master to be freed, for in 1797 it appears Mintus and Captain Henry struck a deal: if Mintus continued as a slave until his twenty-first birthday, Captain Henry would then free him. The author suspects this was the agreement based on Captain Henry in 1797 including the following clause in his will: “And to my servant man by the name of Mintus I will and bequeath his freedom from servitude from and after the first day of September one thousand seven hundred and ninety-eight.”[20] By specifying the date, in the event Captain Henry was killed in an accident or by a sudden illness, Mintus would be assured of obtaining his freedom on the agreed-upon date. It turned out that Captain Henry died in 1798, and by the terms of his will, Mintus became a free man on September 1, 1798.[21]

While it is not clear what Mintus did next, as did many freed slaves, he probably was hired as a temporary laborer on a white man’s farm, possibly in the Hoosick area. In about 1804, he moved to what is now Minerva, New York, in Essex County, where a number of white Rhode Islanders had settled and were trying to establish farms in the rugged Adirondacks hills. Perhaps Mintus knew some of them and worked on their farms. By the time of his move, he had probably married Susanna, Solomon’s mother, whom Solomon described as part black, part white, and part Native American.[22] On July 10, 1807, Solomon was born, as a free person.

Around 1808, Mintus and his family moved to the town of Granville, New York, in Washington County, which bordered Vermont to the east. Here, Mintus worked on the farm of Clarke Northup, a white farmer and tanner who was Captain Henry’s nephew. In the 1810 federal census, Mintus was listed as residing independently heading a household in Washington County.[23] By 1818, the family had relocated to Fort Edward, where the federal census showed Mintus heading a household in 1820.[24]

Records indicate that Mintus publicly took the position that when he moved from Rhode Island in 1790 he was free, but there is an explanation why he did that. At the time, blacks were being discriminated against and challenged as qualified voters. In a presentation made before Fort Edward town officials on April 25, 1821 intended to show that he was a free man entitled to vote, Mintus stated that he had always understood that he had been born a free man in North Kingstown, and that since his arrival in Washington County at the age of twenty years “he had acted and continued to act as a free man.”[25] However, the former statement does not appear to be accurate. The execution of Captain Henry’s will manumitted Mintus in 1798, an event that was confirmed in Solomon’s memoir. In order to vote, Mintus only had to establish that he was free at the time of the voting in 1821, which he clearly was. It is not known why he made the argument that he had been born free. Perhaps he thought it would increase the chances of his voting being respected. In addition, to vote, Mintus had to own a minimum threshold of property. According to Solomon, Mintus did qualify to vote, which was obviously important for Mintus, judging by his efforts to secure his vote.

In 1909, John Henry Northup, whose uncle was Captain Henry, in a letter to a relative, wrote “Mintus lived a mile or two east of Fort Edward.” John Henry fondly recalled that when he was a boy, “Mintus used to come to Sandy Hill and make little beds in the garden for each of us children. He gave his boys a common education.”[26]

Solomon, in his memoir, gave his father a touching tribute:

Though born a slave, and laboring under the disadvantages to which my unfortunate race is subjected, my father was a man respected for his industry and integrity, as many now living, who well remember him, are ready to testify. His whole life was passed in the peaceful pursuits of agriculture . . . . Besides giving us an education surpassing that ordinarily bestowed upon children in our condition, he acquired, by his diligence and economy, a sufficient property qualification to entitle him to the right of suffrage. He was accustomed to speak to us of his early life; and although at all times cherishing the warmest emotions of kindness, and even affection towards the family, in whose house he had been a bondsman, he nevertheless comprehended the system of slavery, and dwelt with sorrow on the degradation of his race.[27]

Mintus died on November 22, 1829, at the age of 51, and was buried in the Baker Cemetery in Sandy Hill (now Hudson Falls), New York. Solomon, who had married in late 1828, was twenty-two-years-old at the time. Solomon’s mother, Susanna, moved to western New York. She died while Solomon was held as a slave in Louisiana.[28]

Mintus raised a talented son in Solomon, who learned not only to farm and cut timber, but to read and write and play the violin. It was fortunate for Solomon that Mintus maintained good relations with the white Northup family. While a slave in Louisiana, Solomon managed to get a letter to Henry B. Northup in Sandy Hill. Solomon knew that Henry B. Northup was a prominent Sandy Hill attorney who was also Clarke Northup’s son and had grown up knowing both Mintus and Solomon. Solomon selected the right man for the task of rescuing him from the horrors of his illegal servitude.

Tim Cranston discovered that sometime after the Northups of North Kingstown sold their homestead farm in the 1830s, the new owner had all of the remains from the Northup family graveyard, both masters and slaves, moved to a newly purchased lot in nearby Elm Grove Cemetery, which opened in 1851. Cranston added in a recent article he authored, “I visit these folks from time-to-time over there in the quiet solitude of Elm Grove and contemplate their graves, the white Northups with their fine slate stones carved with care and precision in Newport, and the slaves of these folks, the very kin of Solomon Northup, marked only by simple fieldstones, and think about the very different lives they led.”[29]

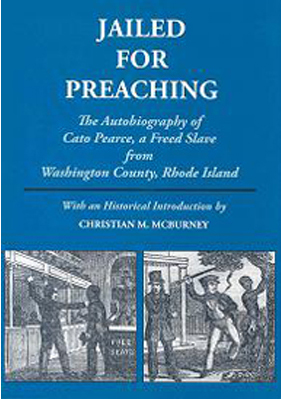

In researching Mintus Northup, I wondered whether or not he might have met another North Kingstown slave, Cato Pearce. In 2006, I republished Cato Pearce’s autobiography, the only memoir written by a Rhode Island slave. Cato was born a slave in North Kingstown in 1790, the same year that Mintus moved to New York State, so they never met each other. Cato remained in Rhode Island, only to be whipped several times by his masters, and suffer other degradation even after he became free, but throughout all his dignity shined and he became a renowned preacher.[30] [1] Chaput, Erik J., “A Website Brings Narratives of Slavery Out of the Past,” Providence Journal, Oct. 13, 2013; Cranston, Tim, “The View from Swamptown, North Kingstown’s Ties to ‘Twelve Years a Slave,’” North East Independent, May 23, 2014.

[2] Northup, Solomon, 12 Years a Slave (New York: Penguin Books, 2013), 5-6. This book is one of several reprints published in 2013 based on the original 1853 publication. [3] See McBurney, Christian, Jailed for Preaching, The Autobiography of Cato Pearce, a Freed Slave from Washington County, Rhode Island (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2006); McBurney, Christian, “The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History, vol. 45. no. 3 (August 1986), 82-93. [4] Unless otherwise stated, information on the Northup family in this article is from Wyckoff, Edith Hay, The Autobiography of an American Family (Fort Edward, NY: The Washington County Historical Society, 2000). [5] Cranston, “North Kingstown’s Ties to ‘Twelve Years a Slave,’” North East Independent, May 23, 2014. [6] Fiske, David; Brown, Clifford W.; and Seligman, Rachel, Solomon Northup, The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013), 19. [7] Smith, Joseph Jencks (ed.), Civil and Military List of Rhode Island, 1647-1800 (Providence, RI: Preston and Rounds Co., 1900), 49-123 (sheriff), 137-195 (justice), 266 (chief justice), and 91 and 96 (colonel); Bartlett, John R. (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island . . . . , vol. 4 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1859), 572 (deputy in 1740); Bartlett, John R. (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island . . . . , vol. 6 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1860, 47, 203, 249, and 523 (deputy in 1757, 1759, 1760 and 1767). [8] Bartlett, John R. (ed.), Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island . . . in the Year 1774 (Providence: Knowles Anthony & Co., 1858), reprinted by the Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore, MD, 1990, 80. Some Rhode Island blacks were free servants. Because in 1790, the blacks listed as residing in the household of Captain Henry Northup’s were all listed as slaves, the author assumes that the blacks in Immanuel Northup’s in 1774 were also all slaves. [9] Northup, 12 Years a Slave, 8. [10] It is not certain when Mintus was born—there are discrepancies in the records. In a written statement filed by Mintus on April 25, 1821, with the town of Fort Edward, New York, Mintus stated that at the time, he was forty-five years and eight months old. Bascomb, Robert O., The Fort Edward Book (Fort Edward, NY: James D. Keating, 1903), 162. If accurate, this would mean he was born in August 1776. However, according to his cemetery marker, he was born in 1778. See image of the stone in Wyckoff, Autobiography of an American Family, 122. For the reasons stated in the text below associated with notes 20 and 21, the author believes Mintus was born on August 31 or September 1, 1777. [11] Holbrook, Jay Mack (ed.), Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979), 89. [12] See, e.g., Boston Post, Nov. 16, 1772; Providence Gazette, June 19, 1773; Newport Mercury, May 30, 1774. [13] See “Record of Marriages by Rev. Gardner Thurston, Pastor of the Second Baptist Church, Newport, R.I., 1759-1800,” Magazine of New England History, vol. 1 (Newport, R.I., 1891), 246 (marriage occurred on December 20, 1774); Newport Mercury, Jan. 3, 1774. [14] Bartlett, John, R. (ed.), Records of the State of Rhode Island . . . 1776 to 1779, vol. 3 (Providence: Cooke, Jackson & Co., 1863), 322 and 344. [15] McAleer, Althea H., Elm Grove Cemetery Inscriptions, North Kingstown, Rhode Island (Rhode Island Genealogical Society, 2000), 60 (based on Immanuel’s gravestone). [16] North Kingstown Probate Records, 1790, North Kingstown Town Hall. [17] Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Rhode Island (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908), 44. [18] Niles, Grace Greylock, The Hoosac Valley, Its Legends and Its History (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 237-38. [19] Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Rhode Island, 44. [20] Image of clause is in Wyckoff, Autobiography of an American Family, 121. [21] Captain Henry’s wife, Mary, also died in 1798, suggesting that their household suffered from a contagious disease. See Arnold, James N. (ed.), Vital Records of Rhode Island, 1636-1850, vol. XII (Providence: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1901), 58 (Mary died at Hoosick Falls, aged 46 years, reported by a newspaper on June 20, 1798). [22] Fiske, Brown and Seligman, Solomon Northup, 20 and 24. This book is the most complete and accurate history of Solomon Northup. See also Northup, 12 Years a Slave, 7 (wife’s racial background). [23] Jackson, Ronald Vern; Teeples, Gary Ronald; and Schaefermeyer, David (eds.), New York 1810 Census Index (Bountiful, UT: Accelerated Indexing Systems, Inc., 1976), 229. Historians of Mintus have previously missed this reference. His name is misspelled as Mintrus Northrup. [24] Fiske, Brown and Seligman, Solomon Northup, 23; Jackson, Ronald Vern (ed.), New York 1820 Census Index (South Bountiful, UT: Accelerated Indexing Systems, Inc., 1977), 338. [25] Quoted in Fiske, Brown and Seligman, Solomon Northup, 172, n. 5. Mintus’s statement, and supporting affidavits of white men who had known Mintus after he was freed in 1798, are preserved at the Fort Edward Town Clerk’s office. Id. [26] Quoted in Wyckoff, Autobiography of an American Family, 121. [27] Northup, 12 Years a Slave, 6-7. [28] Fiske, Brown and Seligman, Solomon Northup, 24. [29] Cranston, “North Kingstown’s Ties to ‘Twelve Years a Slave,’” North East Independent, May 23, 2014. The Northup graves were moved to lot 147. McAleer, Elm Grove Cemetery Inscriptions, 60. McAleer wrote, “A few lots contain those whose identities are not known, such as lot 147 with twenty graves, ten marked unknown.” Id., v.[30] McBurney, Christian, Jailed for Preaching, The Autobiography of Cato Pearce, a Freed Slave from Washington County, Rhode Island (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2006).