Last week, this website ran an article providing strong contemporaneous evidence that many of the men who broke open the tea chests and destroyed the tea inside them on board three ships at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston Harbor in the evening of December 16, 1773, disguised themselves as Narragansett Indians—and not as Mohawks, as is often claimed in histories of the Boston Tea Party.[1] This result was not surprising, given that when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620, and Puritans poured into Massachusetts Bay in the 1630s, the most numerous and powerful tribe in southern New England was the Narragansett.

The 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party is on Saturday, December 16, 2023. It was arguably the most important incident that led to the American Revolutionary War and American independence. (Though, arguably, it was the overreaction to the Boston Tea Party by Britain’s Parliament that spurred the rebellion.)

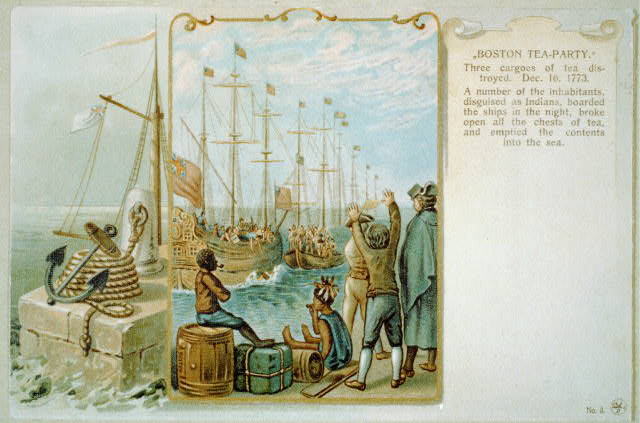

A Black man and an Indian man sit and observe the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, ca. 1903 (Library of Congress)

This article argues that those who planned, participated and/or wrote contemporaneously about the Boston Tea Party thought of using a disguise as Narragansetts from the reports about another famous incident of violent resistance to British Crown rule—the sinking of the Gaspee in 1772 in Rhode Island. This is the first time this argument has been made to the author’s knowledge.

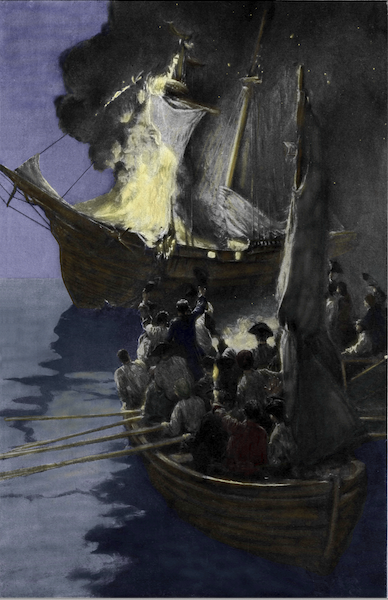

In the first part of 1772, the crew of the eight-gun schooner Gaspee, commissioned to enforce Parliament’s revenue acts in Narragansett Bay, had been stopping vessels, seizing goods, stealing sheep and hogs, and committing other depredations along the shore. Many Rhode Islanders did not believe the Gaspee’s commander was acting lawfully; and if the commander was acting lawfully, Rhode Islanders still did not like it. On June 9, while pursuing a Providence packet vessel, the schooner ran aground. Providence merchant John Brown and one of his sea captains, Abraham Whipple, the same night, organized a party of mostly Providence men in eight small boats—eight to a boat, reportedly—to attack the stranded Gaspee off Namquit Point in Warwick. The British vessel’s captain, Lieutenant William Dudingston, surprised during his slumber and in his nightshirt, rushed to the top deck with sword in hand and tried to organize his men to resist but his crew surrendered after he received a musket ball in the groin from a musket fired by one of the raiders. Dudingston survived, but his vessel was burned to the water’s edge.

The Gaspee being set on fire by Rhode Islanders in small boats, one of the outstanding acts against British imperial rule before the commencement of the Revolutionary War. The Gaspee burned to its waterline after its capture (Harper’s magazine)

Naturally, British government authorities wanted to know who perpetrated the attack and punish those convicted of the same. Raiders who were caught could have been charged with treason, convicted, and sentenced to hang.

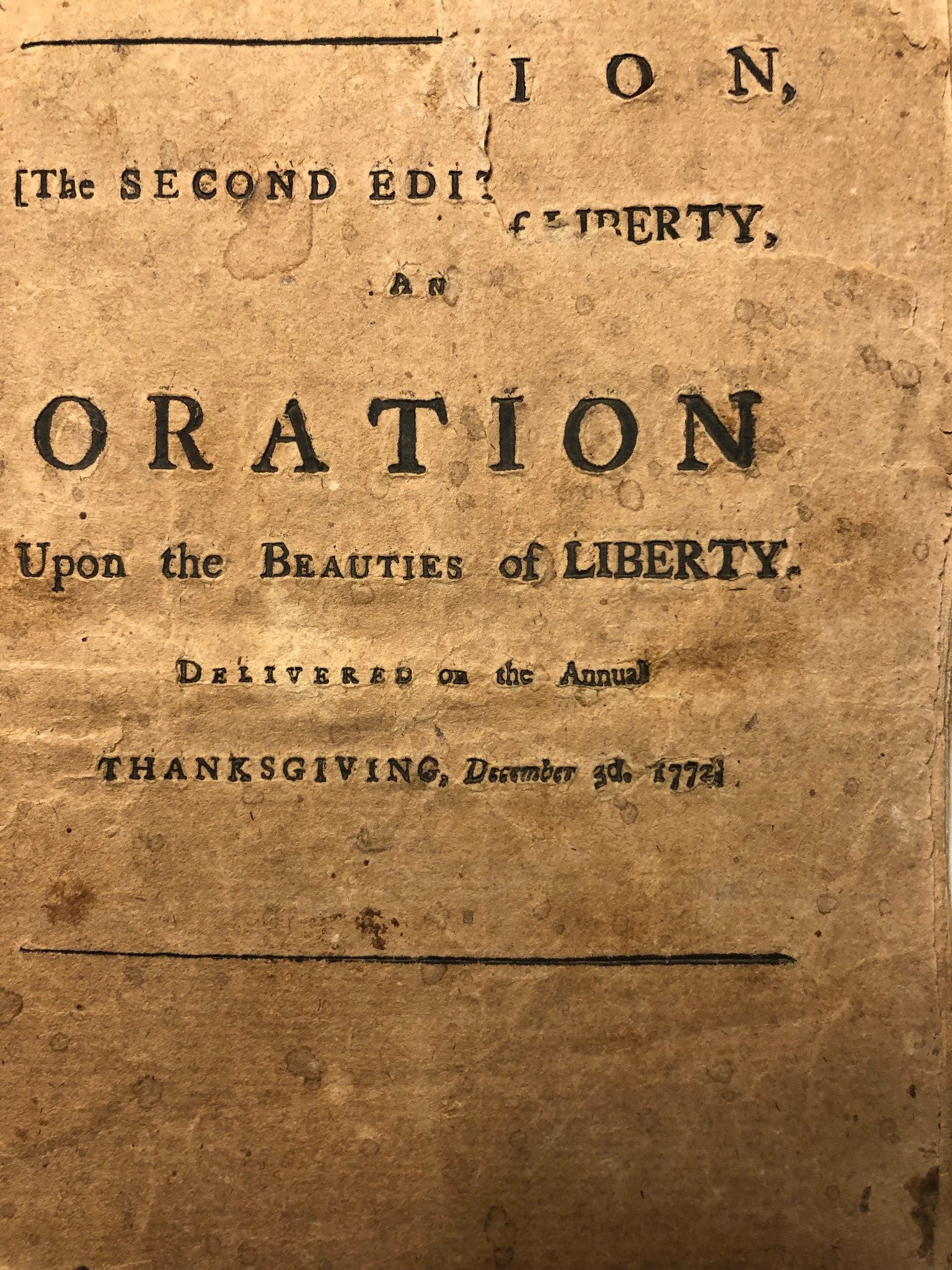

The possibility of the attackers disguising themselves as Indians was mentioned in a pamphlet published in 1773, prior to the Boston Tea Party, written by John Allen, a minister from Newburyport, Massachusetts. The pamphlet, one of the most popular in the thirteen colonies, had as a major argument that the burning of the Gaspee was an important blow against British tyranny.[2] The pamphlet derived from a sermon Allen gave on December 3, 1772—almost a year before the Boston Tea Party.

In his pamphlet, Allen wrote, “the Gaspee Schooner is destroyed . . . by Indians out of the woods, or by Rhode-Islanders, I cannot say who . . . .” He added that “the current report” was that the raid on the Gaspee “was done by the INDIANS.”[3] Allen did not name the tribe of Indians, but it was common knowledge that the main Native American tribe of Rhode Island was the Narragansett.

By early 1773, Allen had heard the rumor that Narragansetts were the perpetrators of the attack on the Gaspee. He may have heard of an unfounded accusation in a Providence newspaper. According to a July 24, 1772 letter published in the Providence Gazette’s August 22, 1772 edition, Lieutenant Dudingston had been wounded by “the Narragansett Indians in a riot.”

It may also have been the case that Allen was aware of a ballad about the burning of the Gaspee that read in part:

Some Narragansett Indian men

Being sixty-four, if I remember

Which made the stout coxcomb [i.e., Dudingston] surrender

And what was best of all their tricks?

They in his breech a ball did fix.

There is good evidence that this ballad was written and circulated in New England prior to the Boston Tea Party. If that was the case, then it must have influenced the participants in the Boston Tea Party to disguise themselves as Narragansett Indians.

The only broadsheet containing the ballad known to still exist is held by the Rhode Island Historical Society.[4]

The font used in the broadsheet is consistent with that of broadsheets printed in colonial times prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. The Rhode Island Historical Society states that the broadsheet could have been printed in 1772 (though the year it is not certain) and that the printer of it was Solomon Southwick of Newport, who by 1772 was the colony’s premier printer.

Burning of the Gaspee in 1772. Gaspee Magic Lantern Slide, Artist Unknown. Purchased in Scituate by John Concannon.

Handwriting at the top of the broadsheet reads: “Theodore Foster’s”. This note suggests that Theodore Foster penned the ballad. Alternatively, the handwritten note could have meant that the broadsheet belonged to Foster. The former appears to be the most likely possibility and the Rhode Island Historical Society website agrees.[4] The broadsheet was found in Foster’s papers.[5] Foster was a respected Providence Patriot during the American Revolution and he resided in Providence prior to the outbreak of the war. He was about twenty years old in 1772.

The first time this ballad appeared in a book was in 1842 in John S. Taylor’s Sketches of Newport and Its Vicinity.[6] The stated source for the ballad was also Theodore Foster’s papers.

The writing of the ballad has also been attributed to Captain Thomas Swan of Bristol, Rhode Island, who was said to be one of the men who attacked the Gaspee. This claim was first made by the historian Wilfred H. Munro in his The History of Bristol, R.I., The True Story of Mount Hope Lands.[7]

In a later book by the same author, Tales of an Old Sea Port, the following report appeared:

The only “lyric” to commemorate the [Gaspee] affair came from the pen of Captain Thomas Swan of Bristol, one of those who took part in it. His effusion has never appeared in any history of American literature, for good and sufficient reasons, but it is printed in full in Munro’s “History of Bristol” . . . .

In January, 1881, Bishop Smith of Kentucky, born in Bristol in 1794 and a graduate of Brown in 1816, wrote to me calling my attention to a slight difference between the “Swan Song,” as I had given it in my History of Bristol, and a version pasted upon the back of a portrait of Thomas Swan’s father by Thomas Swan himself. Capt. Swan was Bishop Smith’s uncle. The Bishop wrote, “I should not have troubled you on so inconsiderable point had not the tradition in our family been that the Bristol boat was manned by men in the disguise of Narragansett Indians.”

When Bishop Smith penned these lines several men were living in Bristol who had heard the story from Captain Swan’s own lips. He delighted in telling it and was accustomed to give the names of Bristol participants [in the Gaspee affair].[8]

In 1845, Judge William Staples, in his useful book, The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee, addressed a tradition that some of the participants in one of the eight small boats under Captain Simeon Potter of Bristol (including, reportedly, Thomas Swan) were dressed as Indians. Judge Staples expressly said, “The parties assumed no disguise of any kind, but went in their usual dress.”[9]

An 1895 Rhode Island Historical Society publication also did not take the claim seriously. The authors of this publication concluded, “There is direct evidence that those who took part in the expedition were dressed in citizen’s clothes” and they also quoted Judge Staples. Next, the authors quoted Charles DeWolf Brownell of Bristol, the artist of the most famous painting of the Gaspee affair, The Destruction of the Gaspee. Brownell replied that reports of “the Indian attire were in in his opinion, untrustworthy.”[10] Brownell did not paint the attackers as dressed like Indians.

The cover of a pamphlet by the Reverent John Allen which described the sinking of the Gaspee as an attack on the British monarchy. It was one of the most popular pamphlets of the colonial period. (Photo by Christian McBurney, from an edition held by the Library of Congress)

The most authoritative account of the Gaspee raid in a book today is by Steven Park, in his recent The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee.[11] In the main text of his book, Park did not mention at all the possibility of the men who attacked the Gaspee as disguising themselves as Narragansetts. He only went as far as writing, “One anonymous source reported that the men blackened their faces and hands.”[12] Thus, he decided that the tradition was not credible enough to even address in his main text. In a footnote, Park mentions Foster’s ballad and quotes Judge Staples’s remark set forth above.

Accordingly, it seems that none of the raiders who attacked the Gaspee from Providence disguised themselves as Narragansett Indians.[13]

So why does the ballad refer to the men who raided the Gaspee as “Narragansett Indian Men”? Accusing Narragansetts of lawbreaking was not nice but no one seriously thought that Narragansetts or any other Indians were to blame for the attack. I agree with the authors of the Rhode Island Historical Society Publication, who in 1895 explained the most probable rationale:

By calling those who performed this daring deed Narragansett Indian men, the poem probably helped perpetuate an evasive answer given at the time to some inquisitive persons who sought to know and identify the men whom the British government wished to apprehend and punish.[14]

Thus, it was a device to discuss the men who attacked the Gaspee, but without having to name them, which would attract unwanted attention from government investigators. After the sinking of the Gaspee, in the second half of 1772 and the first half of 1773, Royal authorities commenced an intense investigation to identify the perpetrators, but in the end failed in their quest. Thus, if one wanted to write about the affair in late 1772 or early 1773, saying that the deed had been accomplished by Narragansetts would have continued the effort to keep the identities of the actual participants a secret. This is yet more evidence that Foster’s broadsheet was published prior to the Boston Tea Party.

Historian Catherine Williams, in her biographies of Revolutionary War heroes William Barton and Stephen Olney of Rhode Island, published in 1839, agreed that this use of the term Narragansett Indians was adopted as a way to disguise the identities of the Gaspee raiders. She wrote,

We would remark that in all the accounts we have seen, of the destruction of the Gaspee, it has been asserted that the company, or a part of them, were disguised as Narragansett Indians. This was not the case. They were not disguised in the least. They merely called themselves Narragansett Indians. They took care however not to call each other by name. In fact there was very little talking done.[15]

Thus, the idea of Crown protestors claiming that Narragansett Indians perpetrated an attack on the Gaspee was floating around in New England in 1773, prior to the Boston Tea Party. But the men who attacked the tea ships in Boston Harbor in December 1773 went one step further—they actually did disguise themselves as Narragansett Indians.

Notes

[1] See J. H. Bell, Narragansetts (Not Mohawks) Blamed for Boston Tea Party,” at https://smallstatebighistory.com/narragansetts-not-mohawks-blamed-for-boston-tea-party/ [2] See Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016), Chapter 5, An Oration. Park concludes that Allen’s pamphlet was one of the most popular in the thirteen colonies based on the number of editions printed compared to the number of editions printed for other pamphlets. Given the paucity of information on the total numbers of editions published or sold, Park’s approach is novel and welcome. [3] John Allen, An oration, upon the beauties of liberty, delivered on the Annual Thanksgiving, December 3d, 1772 (Boston: D. Kneeland and N. Davis in Queen Street, 1773), page x The full pamphlet can be accessed here: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N10250.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext. The first part of the quote is also in Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Gaspee, page 123, footnote 13. [4] The broadsheet is in the Theodore Foster Papers held by the Rhode Island Historical Society. For an image of it on the Rhode Island Historical Society’s website, see https://rihs.minisisinc.com/SCRIPTS/MWIMAIN.DLL/221620063/4/10/20740/WEB_BIBLIO_DETAIL_REPORT?RECORD&UNION=Y. The full text of the ballad, and a black-and-white image of the broadsheet, is set forth at www.gaspee.org/Song.html. The full text is also set forth in Wilfred H. Munro, The History of Bristol, R.I., The True Story of Mount Hope Lands (Providence: J. A. & R. A. Reid, 1880), pages 172-74. [5] Same sources as above footnote. [6] John S. Taylor, Sketches of Newport and Its Vicinity; with notices respecting its history, settlement and geography of Rhode Island (New York: John S. Taylor & Co., 1842), pages 149-52. [7] Munro, History of Bristol, page 172-74. [8] Wilfred Harold Munro, Tales of an Old Sea Port, A General Sketch of the History of Bristol, Rhode Island (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1917), page 21. [9] William R. Staples, The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (Providence: Knowles, Vose, and Anthony, 1845), page 108. [10] “Notes on Landscapes in the Picture Gallery,” in Publications of the Rhode Island Historical Society, New Series, Volume III, No. 1 (Providence, 1895), page 173. [11] Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016). [12] Ibid, page 16. [13] Dr. John Concannon, the operator of the excellent website on the Gaspee incident, however, concludes as follows: “The recorded evidence strongly suggests that the participants who departed in seven longboats from Providence did not wear any disguises. . . . It is most likely that the Gaspee raiders from Bristol, in their single boat, took it upon themselves to be disguised as Indians before they joined up with the rest of the attack boats to confront the Gaspee.” See Dr. John Concannon, “Did or did not the Gaspee Raiders disguise themselves as Indians,” at http://www.gaspee.org/Indians.htm. [14] “Notes on Landscapes in the Picture Gallery,” page 173. [15] Catherine Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes: Containing the Life of Brigadier Gen. William Barton and also of Captain Stephen Olney (Providence, Privately Printed, 1839), pages 19-24.For more on the burning of the Gaspee, see Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Gaspee and Gaspee Virtual Archives at http://www.gaspee.org/index.htm#Controversies.

For more on the Boston Tea Party, see Benjamin Carp. Defiance of the Patriots. The Boston Tea Party & the Making of America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011). Paperback 2020 and many articles by J. L. Bell in his wonderful website at https://boston1775.blogspot.com/ [search for the term Boston Tea Party].