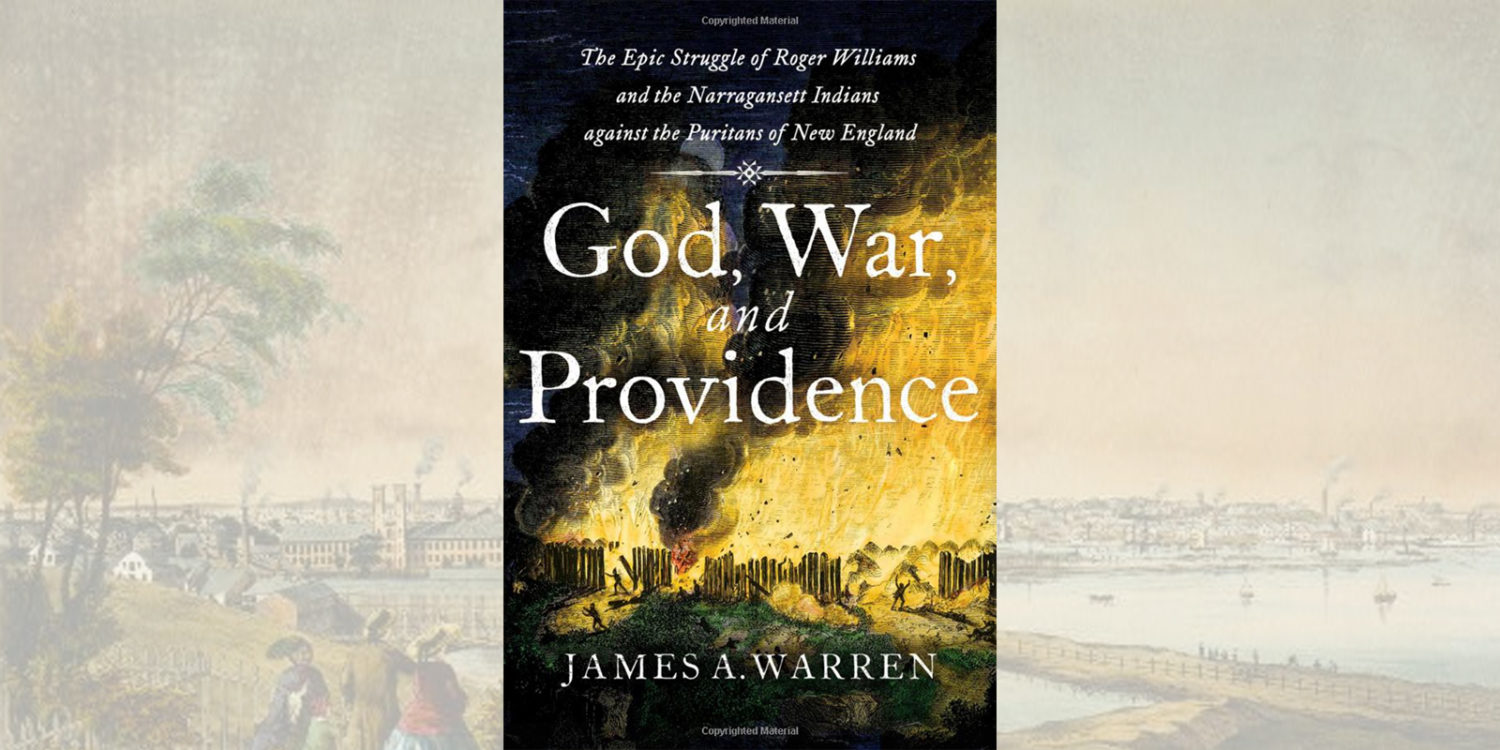

God War, and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians against the Puritans of New England, by James A. Warren (Scribner, 2018).

In God, War, and Providence, James A. Warren has written the best synthesis for the general reader of the seventeenth century struggle between the Puritans of Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well as the Pilgrims of Plymouth, against the Narragansett Indians. Warren has reviewed the scholarly modern articles and books on the topic, and has converted this knowledge into an engaging, easy-to-read narrative.

Warren points out that most books on the topic have taken the viewpoint of the Puritans and Pilgrims, largely because they left a substantial written record, while the Narragansetts did not. He correctly points out the dangers of this approach, given the natural bias of these early settlers in their dealings with Indians. Warren notes that while white narratives have explained the long contest against the Narragansetts, conveniently, many of the treaties between the Narragansetts and the Puritans and Pilgrims have disappeared. This may be because upon a close read of their provisions at issue, it would be found that the Indians had the better interpretation of them. Despite the paucity of the surviving records of the Narragansetts in their own voice, Warren gives their point of view their due.

The book spans the period from the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth and their befriending of the Wampanoag leader Massasoit in 1620, to the Puritans’ war that decimated the Pequot tribe of southeastern Connecticut in 1637, and finally to King Phillip’s War in 1675. At the time, the Narragansetts were the most powerful Indian tribe in southern New England. The Puritans in early Massachusetts, and later in Connecticut, and the Pilgrims of Plymouth, eyed them warily as a potential military rival, and subsequently lusted after their rich lands in southern Rhode Island. Despite the constant harassment from the white leaders, tribal sachems, such as Ninigret of the Niantics based in Charlestown, refused to buckle under the pressure. They used negotiations, delay, and logical arguments to preserve their tribal rights and autonomy.

Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, is an important figure in the book. While he is best known as the father of liberty of conscience and the separation of church and state, this book is not an intellectual history focusing on those sensational achievements (which is the focus of John M. Barry’s biography of Roger Williams). Instead, this book shows Williams purchasing land from the Narragansetts and living side-by-side with them in peace. He takes such an interest in the Narragansetts that he pens an authoritative book on their language and culture, the first ever ethnographic study of Indians in North America. It shows Williams earning needed profits by trading with Indians from his trading post at Wickford. It also shows Williams time-and-time again taking the side of the Narragansetts in their disputes with the Puritans and Pilgrims, or at least trying to get the white leaders to consider the Indian perspective.

Viewing Rhode Island’s early settlers as heretics, the Puritans and Pilgrims began to harass the Gortonists of early Warwick and to connive in London to seize the lands of Rhode Island to make them part of their colonies. Thus, Williams and the Narragansetts joined in common cause to resist the encroachments of the Puritans and Pilgrims. White leaders from Rhode Island aided these efforts by having Narragansett sachems sign a document putting them under the protection of the King of Great Britain, whose representatives in London often would take their side against Puritans whom they often distrusted.

One example of nefarious dealings by the Puritan oligarchy involved the so-called Atherton purchase of 1662. It started out when Puritan authorities in Boston imposed a huge fine on the Narragansetts for some perceived offenses. Knowing that the tribe could never pay the debt, the white leaders also managed to get several sachems to sign a mortgage securing the so-called debt to their entire territory, some four hundred square miles, including all of what is now South County. Suddenly, Major Humphrey Atherton of Massachusetts, leading a group of private Massachusetts and Connecticut investors, stepped forward and paid the debt. Now his Atherton Company held the mortgage. The Atherton Company, in a short ceremony on Pettaquamscutt Rock, foreclosed on the mortgage, and in this way claimed ownership of the lands of the Narragansetts (who were still allowed hunting rights). Warren thinks Massachusetts officials colluded with the Atherton Company, probably thinking that such a blatant land grab by the colonial Massachusetts government would not withstand Royal scrutiny, while it would be more difficult for private investors to have land taken away from them. Seeing this land grab as an effort that could also undermine the future of an independent Rhode Island, Williams and other Rhode Island leaders appealed to Royal authorities in London for assistance. A Royal commission sent to New England eventually saw through the ruse and disallowed the Atherton land acquisition. (I would have liked Warren to have discussed in more detail the other famous land deal that was signed on Pettaquamscutt Rock by white settlers, the so-called Pettaquamscutt Purchase of 1658. Warren does speculate that that purchase, by five Rhode Islanders of rich land in South Kingstown, North Kingstown and Narragansett may have been an effort to oppose the designs of Massachusetts.)

Warren ends his relatively short book with a clear-eyed examination of the causes of King Phillip’s War, the bloodiest war in American history for the white population (in terms of the percentage of casualties) and one that marked the end of the power and autonomy of the Narragansetts in Rhode Island. The war was started by Metacom, known as King Phillip, the chief sachem of the Wampanoags, whose lands included parts of Bristol County, with allied bands in what is now Tiverton (the Pocassets) and Little Compton (the Sakonnets). The war expanded into an alliance of several New England tribes against Puritan and Plymouth settlers. Wary about the potential consequences to their tribe, and squeezed between growing white settlements in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Narragansetts refused to join in the conflict. Nonetheless, in a preemptive strike, an army of about 1,000 Puritans invaded southern Rhode Island in the dead of winter in December 1675 and found the Narragansetts’ main fort in the remote Great Swamp in what is now South Kingstown. After the invaders penetrated the palisades and burned down the wigwams inside, the Narragansetts lost their main food supplies during a harsh winter. Narragansett warriors continued the struggle, but the tribe never fully recovered.

Warren, a graduate of Brown University, is a history writer who is a regular contributor to The Daily Beast, MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, and the Providence Journal. He has authored several military history books, including Giap: The General Who Defeated America in Vietnam. He lives in Saunderstown.