Life holds a knapsack full of memories—all of them significant; many, if not most, are worth recording. Growing up in a neighborhood of family and friends was a journey to cherish. That neighborhood and the people living, working, and playing there, though from diverse ethnic backgrounds, had strong traditions of family, caring, and mutual respect. I write of them.

I was grateful for the simplicity of the time, and though I know I can never return, my mind does.

Memories of growing up gave me the incentive to write, and there is no end. These essays of my past assure its permanence for me…of necessity perhaps…to honor not only those who I have loved but also to honor the time in which we lived. I define myself with stories that relive the fun of my early years in a small, easily managed world. It was like a club; one I could enter and leave as I wished. When I entered that club, I was comfortable. When I left, I wanted to re-enter.

Save for the memories, there is little left of the neighborhood and the weave of families that helped to shape my life. These essays are a sentimental glance to a time that made me what I was to become. What I write of stores, streets, schools, houses, sidewalks, streetcars, telephone poles, gardens, neighbors, and friends was in a small world on a few city blocks.

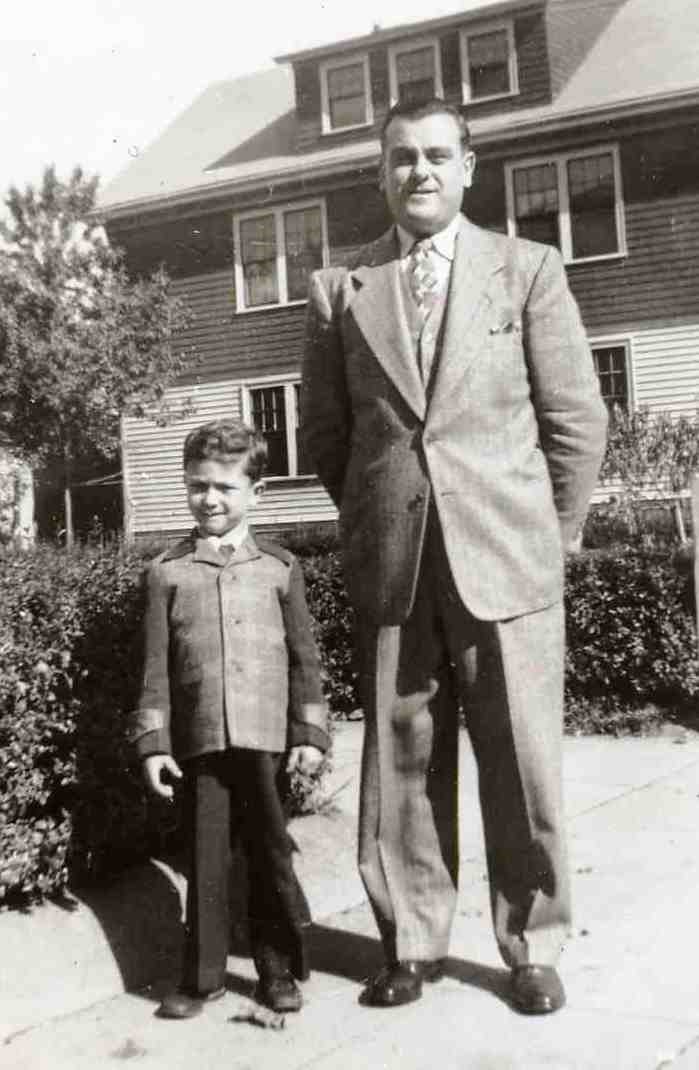

Ed Iannuccilli with his younger brother Peter in front of his home on Wealth Avenue, 1949 (author’s collection)

The neighborhood was a savory stew of people, immigrants, their children, and their children’s children. There was not a face or a voice I did not recognize. Most were Italian or Irish. While my grandmother was singing Vicin ‘u Mare, my mother was singing Fascination, I was singing Earth Angel and someone else was singing Danny Boy. We not only melted into America, but we also melted into each other.

Here are a few stories of my neighborhood I will share with you.

Wealth Avenue

You might think nothing ever happened on this small street; much did. We could sneak a ride on the back of “Joe the Ragman’s” wagon. The Grocery Man might be making deliveries from his huge truck, a traveling store, followed closely by the fruit peddler. On Fridays, the Fish Man appeared, blasting his mouth horn with the message that his truck was filled with a new catch.

The Sullivan Trucking Company was garaged at the end of the street, and the ten-wheelers rumbled by. The Ice Man carried his wares on his back to the tenements above. The fire chief came home for lunch. The Waffle Man served white, sugared waffles from his truck. Another man sold clothing from his car. The Humpty Dumpty Ice Cream Man came at 7 o’clock every evening in the summer, the refrain of his ringing bell heard streets away; the “creamsicles” were delicious!

The neighborhood tenor could be heard rehearsing the national anthem he would sing at Madison Square Garden, and the sounds of the piano students echoed. Kids were playing games. Hopscotch, “alara,” stickball, “peggy,” touch football, hide and seek, and capture the flag.

Domenic washed and polished his car every Saturday. A future Rhode Island governor grew up there. The Russo boys never walked calmly out of their house, they bounded. My third-grade teacher lived there, and sometimes I followed her to school.

There were great places to hide. I was the paperboy. One night during World War II, I cowered behind the curtains while helmeted air-raid wardens patrolled our darkened neighborhood.

What a marvelous street Wealth Avenue was!

Wealth Avenue, part of a trilogy with Health and Wisdom Avenues, truly was a wealth of experience, community and love. It was a straight city street flanked by comfortably spaced bungalows, cottages and two- or three-deckers whose doors spilled directly onto the sidewalks. There was an occasional garage, and one empty lot. There was only one front lawn; all the others were in the back.

Sturdy curbstones defined cement squares, embedded at regular intervals with small, commemorative plates to acknowledge the Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers who so proudly built them during the Great Depression. The sidewalks were lined with tall utility poles, the letter “t”, linked by swayed telephone lines. Here and there, a netless basketball hoop might be nailed to a pole that might also be used as a goal in hide and seek.

Streetlights were suspended from the middle of the poles, with circular, scalloped metal “hats” covering the bulbs. When the lights were lit, a yellow haze emanated and created dancing shadows on the street below. They were our summer-evening clocks.

“Come home when the streetlights go on,” my parents would say. “Can I stay out if I stand under the streetlight with my friends so you can see me?” was my question in response.

Wealth Avenue was perpendicular to the main thoroughfare, Academy Avenue. Its beginning was bracketed by a barbershop and a bakery, and its end marked by a row of four rental garages. Our house was third from the end, and the best vegetable garden on the street, my grandfather’s, was next to it.

Cars and houses were never locked. There were no broken windows. Nothing dreadful ever happened, but something was always happening.

On snowy winter days, the residents took to the sidewalks to shovel. Piles of snow left along the curb were an open invitation for climbing, tunneling, and trying to walk atop their entire length. Inevitably, the snow tumbled back down as we played, and some neighbors were annoyed.

Not my grandfather. He was our shoveler and he had a methodical way of reclearing the sidewalk, which he did without 9omplaint when we unseated the snow.

I loved Wealth Avenue! I wanted the street to stay the same forever. It could not, and on a recent visit there, it did appear different. It seemed, not unlike people, to have become smaller and shorter with age. But it hasn’t altered my memories. I embrace my past on Wealth Avenue with affection.

Putnam Street School

I loved kindergarten (“kindygaaten”), and I loved Putnam Street School. It was a two-story, gray brick building with a tiled roof and was perched atop a hill along a busy street. A high granite wall topped by a fenced-in asphalt schoolyard fronted it. To its rear was a sandlot, a small tract of land that served as a stickball field in summer.

Double doors led to a small entry and narrow, uneven wooden corridors flanked by rooms for K-3 on either side. There was a “bubbler” (permission needed) at mid corridor. Along the way was an “ungraded room” for kids who were “diffeient.” The walls on each side of the corridor were lined with coat hooks; the last room on the left was mine.

Circular globes hanging from above lit the corridor. Each room had rows of tiny desks with inkwells at their top right corners. Oversized teacher’s desks, seats backed to the blackboards, were on platforms at the front.

My mother and my aunt took me to Putnam Street School on my first day. They joined a friend who was taking her son, Joe, who didn’t want to go. Our mothers left us there, assuring us they would return. When I walked in the front doors, I discovered a mingling of scents that I learned to love; wooden floors, books, crayons, ink and starchy glue. The kindergarten room was so nice. Tall windows joined two walls of the room and let in clear, bright light when Miss Walsh raised the shades. She reassured our mothers that we would be fine.

I wasn’t sad. I was at school with a tall, blond, pretty teacher who instantly became the most important person in my life. She assigned me a wooden locker along one side of the room and wrote “Edward” on its door. It was stocked with my own crayons in a crayon box, white glue, clay, a few books, and a blanket. My desk was a table…more books…that I shared with others.

After coloring and drawing, it was time for our mid-morning nap. We went to our lockers, got our blankets, and spread them on the floor. The lights were dimmed, the shades pulled down and the curtains closed. Miss Walsh left the room. “Make sure you rest. No one is to get up.”

We didn’t nap. We played. Teacher gone, we used the blankets for sleds, taking a running start, then belly landing on the blanket for a slide across the polished floor.

Nap?

Joe wasn’t happy. He wanted his mother. He wanted but. He crept up to me and whispered, “Let’s go find our mothers.”

“Okay.” Joe was my friend.

I accompanied him out the classroom door, down the corridor by the bubbler, the classrooms and the coats. Five years old, we walked out of school, unobserved. Down the hill we went to the traffic light, crossed the busy street, and set out to find our mothers.

We walked by the market owned by Joe’s father. We made, our first stop at my house, six blocks away. Mothers not there. We proceeded to Joe’s home, six blocks down the hill. Mothers not there. Hungry and tired, we walked back to the market, across the street from the school.

By then, everyone—a policeman, the crossing guard, the principal, Miss Walsh, Joe’s father, and our mothers—were there! We looked around, sensing a problem. Everyone except Miss Walsh, the guard, and the cop, hugged us. I looked at Miss Walsh. She was my friend.

Fishamen

“When the ‘Fishaman’ comes by, get a pound of filet,” said Mom. It was her usual Friday request. It didn’t matter where I was or what I was doing, I could hear the horn…baaa, ba, bahh…baaa, ba, bahh. Down the stairs of the three-decker and around the corner I flew, sixty cents (I think) in hand.

He stopped his dark green panel truck in the middle of Wealth Avenue. Laden with dead fish covered in ice, it had open sides with canvas rolled to the top and tied with thick rope, a Fish Man’s knot, I guess.

Firm fish of all kinds were on display, neatly arranged, right side up, eyes open, in wooden sections fitted to the bed of the truck, a roof above protecting the catch from the hot sun. Fillets, shellfish and lobsters were stacked separately. A scale, secured with a chain, hung from a hook screwed into the top rear “two by four.” There was dried blood along the sides of the truck. Melting ice water dripped from the tailgate. The tires were low, burdened with a packed catch. And there was the aroma, fishy the only way to describe it…musty, damp and salty also.

“Pound-a-fillay?”

“Yup.”

“Anythin’ else?”

“No, thank you.” The only time we bought more was during Christmas week.

That was it, no further conversation. Not that there should have been, though he had been coming for years, and I thought so. To a kid of eight or nine, he seemed gruff, grumpy and a little frightening. He was unshaven and bore the vaporous look of exhaustion. His canvas coat was stained with dried blood and oils, and he wore an old New York Yankees baseball cap, the brim discolored where he adjusted it, tipped to the side. His high rubber boots were too big and flopped against his knees when he shuffled around the truck. He grabbed the fillet, flopped it onto the scale…perfect, one pound. He had picked up many pounds in his lifetime.

“This okay?”

“Yes.” He wrapped it in newspaper. “Did you catch all this fish?” I wanted to ask, but never could. The sale was done with no time wasted. The truck’s engine continued its steady, low, idling rumble through the process.

The “Fishaman” went to the door of the truck, stepped up on the running board, entered, sat, clutched, pulled the stiff shift forward and drove away around the corner, letting the clutch out gently. Water dripped from the rear of the truck and left a semicircular trail on the tar. The chain of the scale rattled in rhythm. His elbow leaned out the open window. His thick, calloused hand, surfaced with healing cuts, grasped the horn and held it to his pursed lips. His cheeks bellowed. Baaa…. baaa…ba, ba, ba…baaa….

We moved from Wealth Avenue and the “Fishaman” to a neighborhood of white, single-family homes. Some years later, I was home from college and heard a familiar sound in the distance. It was the horn, the “Fishaman’s” horn…baaa…ba, bahh…baaa…ba, bah . . . blaring with the strength of old, announcing his entry into the neighborhood. I ran toward the truck. There he was …unchanged, unshaven, tired, same truck, same blood, same hat, same boots…flap…shuffle…wearing the same canvas coat.

“Hi, how are you?” I was more confident.

“Is this where you guys moved to?”

“Yes. Where have you been? We missed you.” I was trying to be friendly.

“Aroun’. New rout. Duz ya motha want fish?”

“I’m not sure. I don’t think so.”

“Okay. See ya.”

“Why don’t you just give me a pound of fillet?”

“Okay. Anythin’ else?”

“No, thanks.”

“See ya.”

Baaa…ba, baah…baaa, ba, bah. His elbow hung out the window as he blew his horn, his truck leaving the familiar, semi-circular trail of water as he drove around the corner.