Napoleon Bonaparte said that history is the version of past events that people have decided to agree on. William Jackson was murdered in South Kingstown in 1751, and Thomas Carter was convicted of committing that murder. But there seems to be no agreement about what else happened. The details remain a bundle of quaint stories instead of a narrative of historical facts.

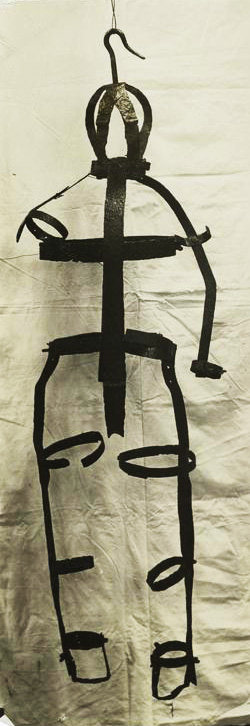

Carter’s hanging took place near a militia training field next to Pettaquamscutt Cove in South Kingstown on Friday, May 10, 1751. His body was gibbeted—placed in irons and suspended in chains from a gallows— and left there to rot. The New York Gazette, probably exaggerating the crowd estimate, reported on May 20: “So. Kingston, May 14. On Friday last, agreeable to the sentence of the Superior Court, Thomas Carter was executed, and hung in Chains, for the Murder and Robbery by him committed on the Body of William Jackson. In the morning an excellent sermon suitable to the occasion, was preach’d by the Rev. Dr. McSparran, from Luke xv. 7. The whole Affair was conducted with the utmost Decency and good order, amidst a crouded multitude of Spectators, supposed, on a very moderate Computation, to exceed 10,000.”[1]

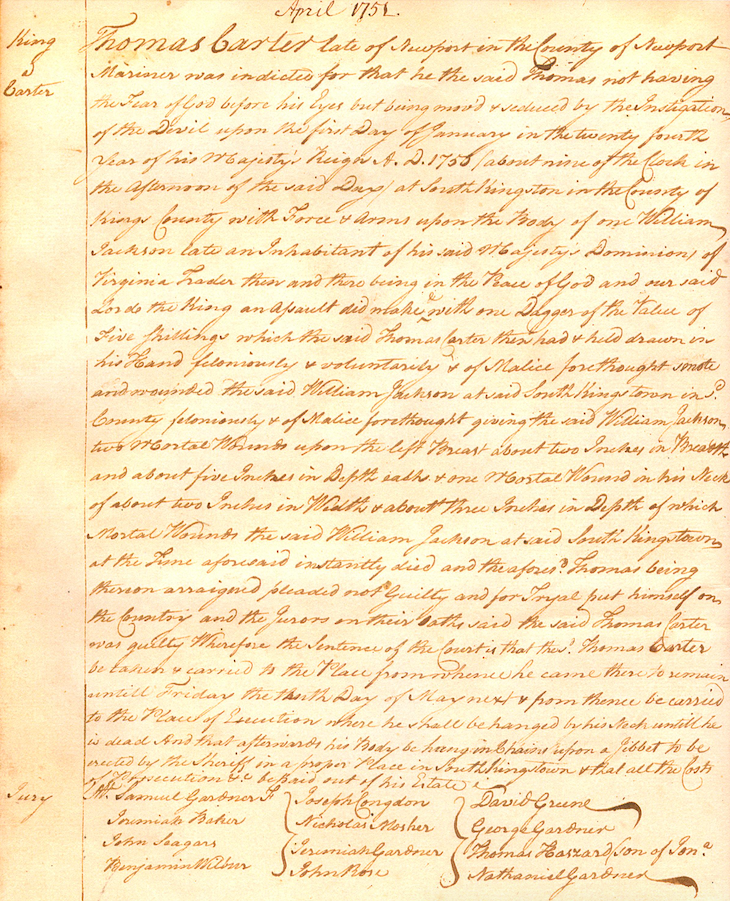

Part of the court record related to the murder trial of Thomas Carter. The jury members are named at the bottom (King’s County Court Records, Rhode Island Judicial Records Center)

In England and its colonies, gibbeting was permitted by common law; in 1752 it was authorized by statute “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder.”[2] South County author Esther Bernon Carpenter, recounting an incident in the mid-1750s travel diary of one Jacob Bailey, wrote that a few years after the execution, Bailey stopped at the Case Tavern in the village called Tower Hill[3] that was once located at the intersection of Tower Hill Road (Route 1), Torrey Road, and Saugatucket Road. Carpenter continued:

“According to the custom of the time, mine host met the traveller and his companions outside the door, bidding them welcome to Tower Hill, serving out wine to them, and doing the honors of his table at dinner, while entertaining his guests with an account of the murder of one Jackson, an itinerant dealer in skins, by Captain Thomas Carter of Newport, his chance travelling companion. “We found the squire to be a most prodigious loquacious gentleman. He offered to wait upon us down the hill to see the murderer as he hung there in gibbets . . . we beheld the sorrowful sight. The man had been there three years already, and his flesh was all dried fast to his bones, and was as black as an African’s.”[4]

Writing almost a hundred years after the murder and conviction, Wilkins Updike, grandson of the colonial attorney general Daniel Updike, who prosecuted Carter, said: “The tragic circumstances under which the homicide was committed, and at a time when crimes of such enormity were rare, awakened the sympathy of the whole continent, and even reached the mother country. The deep interest it created, tradition has detailed in all its minuteness.”[5]

With all the attention paid to the crime and its consequences, one would expect the details to be well-documented. Instead, it seems that many historians have constructed their own version of the story from a smorgasbord of free-floating information.

The story has been told many times over the centuries. Updike, a lawyer, wrote about it in the 1840s in his Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar. Thomas Robinson Hazard, known as “Shepherd Tom,” recounted the crime in his Recollections of Olden Times as well as in his Jonny-Cake Papers, compiled and published by his grand-nephew Rowland G. Hazard in 1915.

At the end of the 19th century, antiquarian James N. Arnold published in his Narragansett Historical Register documents related to the murder, including the entire text of Rev. James McSparran’s sermon, and Kings County Sheriff Beriah Brown’s acknowledgment of receipt of £50 for the expenses incurred in the hanging and gibbeting.[6] During the same era, J. R. Cole’s History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island included an item about the case. Retired University of Rhode Island president Carl R. Woodward wrote about Rev. McSparran’s sermon in Plantation in Yankeeland, published in 1971, and South County native Oliver H. Stedman included an item about the crime in A Stroll Through Memory Lane in 1998. Daniel A. Hearn included it in his book on executions in New England between 1623 and 1960. Undoubtedly those are not the only accounts.

Thomas R. Hazard and his brother Joseph Peace Hazard were devotees of spiritualism, the popular 19th century movement whose adherents believed that spirits of the dead can communicate with the living. On his deathbed, Thomas reportedly said to Joseph, “I am afraid that I am better, and am sorry, for I am anxious to commence the new life in the spirit world.”[7] In 1889, Joseph Peace Hazard had a granite pillar erected at the site of the murder. The pillar is just north of present-day Wakefield, across the street from the state office building. The coordinates are 41° 26.912′ N, 71° 28.414′ W.[8] (For South County natives, it’s in front of the field where Dr. Kaplan’s corral used to be.)

Today, the location of the pillar is a busy intersection. But when the murder took place, it was a sparsely-populated stretch of the Post Road, the main north-south route along the Atlantic coast. Here is the text on the pillar:

“This pillar is erected to the memory of William Jackson of Virginia, who was murdered upon this spot by ship captain Thomas Carter of Newport, Rhode Island, who, having been ship-wrecked, and rendered penniless thereby, and being overtaken by Mr. Jackson, who, also being on his way north, furnished him with money and use of a horse on the way; having arrived at the point that is indicated by this pillar, Carter there robbed and murdered his kind and confiding benefactor with a dagger, about the hour of midnight of Jan. first, 1751, was tried and convicted of his crime at the village of Tower Hill on April 4th, 1751, and was hung in chains upon a gibbet May 10th, 1751, at the eastern foot of the public highway where the shrieking—as it were—of its chains, &c., during boisterous winds at night, were the terror of many persons who lived thereto, or passed thereby, one of these being the late Governor George Brown of Boston Neck, who told this writer that such had been his case when a youth, while on his way to the residence of College Tom Hazard that he visited every week. It appears that Carter threw Jackson in the “Narrow River” at the time he committed this murder, and that a negro found him therein, and near the abovementioned gibbet. A wayside inn-keeper, Mrs. Nash, who lived about ten miles westward from Tower Hill, happening to be at this village at the time this body was found, she recognized it as being that of Jackson, by means of a button she had sewn upon his vest only a few hours before he left her house, and that Captain Carter was with him. Carter was therefore arrested, tried, and condemned, and executed accordingly.”

The pillar reports, correctly, that the murder, trial, and execution took place in 1751. Can there be any dispute about that? Apparently, yes. In Recollections of Olden Days, Thomas R. Hazard said the murder took place in the winter of 1741, and in the Jonny-Cake Papers he said it was 1742.[9] As for the date of the trial and conviction, the pillar says Carter was tried and convicted on April 4, but no record can be found of the date the trial began and the date it ended.

What kind of ship captain was Carter? Updike said he was “master of a small vessel.”[10] Thomas R. Hazard said he was an “old privateeersman,”[11] which puts quite a different slant on the story— a privateer is the owner of an armed private ship commissioned by the government to stop, seize and plunder enemy vessels; in other words, a seagoing mercenary, or worse, a lawful pirate. Thomas R. Hazard said Carter was shipwrecked on the “coast south of the Chesapeake,”[12] but Updike said he was shipwrecked on Long Island.[[13] J. R. Cole said Jackson was from Pennsylvania and not Virginia, as reported by all the other sources.[14] Thomas R. Hazard said the travelers encountered each other in Virginia,[15] but Updike said they met in Connecticut.[16]

Where did the weary travelers stop? Updike said that on December 31, they “arrived at South Kingstown and tarried at Nathan Nash’s,” but he does not say where that was.[17] The text on Joseph Peace Hazard’s monument said they stopped with Mrs. Nash, a wayside in-keeper who lived about ten miles west of Tower Hill. But ten miles west of Tower Hill would have put Mrs. Nash in Richmond, the town to the west of South Kingstown.

Thomas R. Hazard said they stopped at the widow Nash’s house on the east side of the Post Road a mile from Dockray’s corner and about two miles southwest of Wakefield.[18] Stedman said they stopped at the Willard Tavern on January 1, not December 31.[19] Old Houses in the South County of Rhode Island, compiled by the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of Rhode Island and published in 1932, also said they stayed at the Willard Tavern, attributing the information to The Jonny-Cake Papers.[20] But the Willard Tavern, which was torn down in the late 1950s, was at Dockray’s corner (the intersection of present-day Post Road, Willard Avenue, and Dockray Street).[21] The Jonny-Cake Papers said Mrs. Nash lived a mile from Dockray’s corner.

Updike, whose relation to the prosecutor may have given him access to details of the trial testimony not available to others, describes Jackson’s appearance this way: “He was dressed in wash-leather small clothes [close-fitting knee breeches], snuff-colored jacket and red duffil over coat, a saw backed hanger [a short, broad sword with a serrated edge that hung from the belt] at his side, and a watch with a green ribbon for a chain.”[22]

When the travelers reached the site of the murder, Updike said, Carter struck Jackson with a stone “and felled him to the ground; Jackson begged for life, but Carter seized Jackson’s hanger, and dispatched him.” Updike said Carter used the hanger to cut a hole in the ice in the Pettaquamscutt River, breaking the hanger in the process, and pushed the body under the ice.[23] Joseph P. Hazard said Jackson was killed with a dagger. Thomas R. Hazard said Jackson was knocked off his horse with a stone, recovered, and ran into a nearby uninhabited house, where Carter overtook him and beat him to death.[24]

Thomas R. Hazard said Carter dragged the body down the hill to a spot in Pettaquamscutt Cove near Gooseberry Island, which is about a mile directly east of the murder scene.[25] Updike said Carter carried the body over his shoulder.[26]

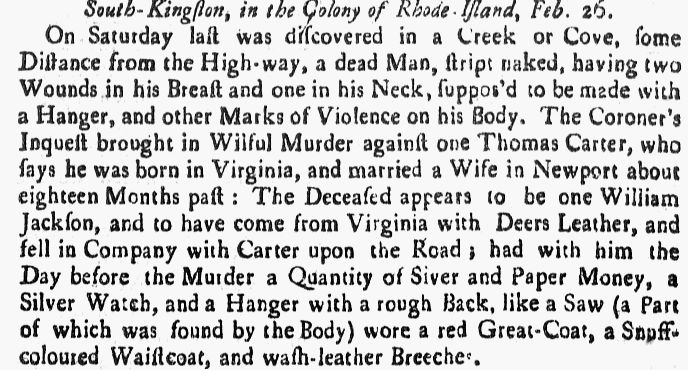

Updike, like the other sources, said the body was discovered by fishermen. J. R. Cole said it was discovered a few days after the murder.[27] Stedman said “a week or two later.”[28] But Updike provides a specific date, February 22, that is probably accurate. A contemporary report that appeared in the March 25, 1751 issue of the New York Gazette said: “South Kingston, in the Colony of Rhode Island, Feb. 26. On Saturday last was discovered in a Creek or Cove, some distance from the High-way, a dead Man, stript naked, having two Wounds in his Breast and one in his Neck, suppos’d to be made with a hanger, and other Marks of Violence on his Body. The Coroner’s Inquest brought in Wilful Murder against one Thomas Carter, who says he was born in Virginia, and married a Wife in Newport about eighteen Months past : the Deceased appears to be one William Jackson, and to have come from Virginia with Deer Leather, and fell in Company with Carter upon the road and had with him the day before the Murder a Quantity of Silver and Paper money, a Silver Watch, and a Hanger with a rough Back, like a Saw (a part of which was found on the Body) and wore a red Great Coat, a Snuff-colored Waistcoat, and wash-leather breeches.”[29]

Rowland Robinson, sheriff of Kings County from December 1750 to May 1751[30] (and the great-grand uncle of Thomas R. Hazard’s wife[31]), arrested Carter in the Point section of Newport on February 23 and brought him back to South Kingstown. He was confined in the county jail, then located in the village of Tower Hill, as was the Kings County Courthouse where the trial took place.[32]

Mrs. Nash identified Carter as the traveling companion of Jackson. According to Updike and Thomas R. Hazard, she identified Jackson’s body by a patch of black hair on his head.[33] Updike said she recognized the linens found in Carter’s possession, with the monogram W. I., as belonging to Jackson, and she recognized the buttons she had sewed on Jackson’s overcoat, also in Carter’s possession. The Colonial Dames said the patch of hair was white.[34]

The March 25, 1751 edition of the New York Gazette contained this summary of the discovery of the dead body of William Jackson. A later article covered the hanging of Thomas Carter.

Today, 267 years after the murder, practically any kind of information—some of it actually true—is instantly available on the Internet. But that does not seem to have enabled a narrative of the crime that everyone agrees on.

Hearn appears to have had access to the court records, but he included details in his book that are at odds with every other version of events. For instance, he said Carter and Jackson first met at a roadside inn in South Kingstown the day before the murder and that the next day, Carter followed Jackson up the Post Road, overtook him, and attacked him—which would have been difficult if Jackson rode a horse and Carter was on foot. He said Carter sold Jackson’s horse as well as his leather goods, but the colony later reimbursed Sheriff Beriah Brown four pounds for boarding Jackson’s horse.[35]

In “The Last Gibbet Cage” (described as “a combination of facts, as reported in the historical public record, the author’s personal recollections of what she perceived to be a supernatural experience, and a touch of artistic license”) on www.quahog.org, Susan Taryn McVicar claims to have visited what she calls the “murder stone”— but the one she visited was at the intersection of Tower Hill Road and Torrey Road. After researching the events of 1751, she says, she was “alarmed at how unfair the entire process of the murder trial had been; there were three judges, less than three in the jury, and no witnesses. Nor was there any proof shown that Thomas Carter committed the murder.”[36]

Actually, there were two juries, each with twelve men— one that heard the murder charge, and one that heard the charges that Carter assaulted Jackson and robbed him of his horse, leather hides, and cash— and James N. Arnold recorded their names for posterity. Samuel Gardiner was the foreman of the jury that heard the murder case; the other members were Jeremiah Baker, John Segar, Benjamin Wilbur, Joseph Congdon, Nicholas Mosher, Jeremiah Gardiner, John Rose, David Greene, George Gardiner, Thomas Hazard, and Nathaniel Gardiner.[37] In March of 1751, the Superior Court advertised in the newspapers for witnesses who could identify the items allegedly stolen from Jackson’s that were found in Carter’s possession.[38] Updike said twenty-seven witnesses testified for the prosecution at the trial.[39] Three Associate Justices of the Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Gaol Delivery— Jonathan Randall, John Walton, and Benjamin Haszard— did preside at the trial, but in that period, all trials were conducted by a quorum of the judges appointed to a court.[40]

Rev. James McSparran, rector of St. Paul’s, the Anglican church about two miles north of Tower Hill, was the man to see if you wanted a sermon befitting a momentous and solemn occasion. We know exactly what the minister said in his lengthy sermon on the Jackson murder, thanks to Arnold, who printed the sermon in its entirety in the first volume of his Narragansett Historical Register.[41] Rev. McSparran talked about the difference between a justified killing, as when a judge condemns a criminal to death, and an unjustified one, as when, motivated by covetousness (“which the Scriptures tell us is the root of all evil”), a man kills his neighbor. The sermon provided an example of every type of killing, beginning with the first one, when “the voice of thy brother’s blood, saith the Lord to Cain, crieth to me from the ground.” Life, he said, “is the gift of God. It is a debt we owe to the Lord and Giver of life, to keep it for his service ‘till he is pleased to call for it.”

What we don’t know is when and where the sermon was delivered. The New York Gazette reported that it was delivered the morning of the execution, which took place on May 10.[42] Updike doesn’t say when the sermon was delivered, but he does say that so many people from Newport came over to South Kingstown to attend the hanging that “those who remained were fearful of an insurrection of the slave population, and despatched messengers for their return.”[43]

Woodward said the sermon was preached at the Kings County Courthouse at Tower Hill on April 14, 1751, after Carter was convicted. He also said the sermon prompted the murderer to repent, as “Carter’s written confession, with Dr. McSparran’s interlinings, is a matter of record.”[44] Updike, who wrote extensively about McSparran and his congregation, said, “A paper which is apparently the ‘dying confession’ of Carter, with interlineations by Dr. McSparran, is in the Updike Collection of Autographs in the Providence Public Library.”[45] Stedman said Carter “confessed and told the full details of his crime.”[46] But Carpenter said Carter protested his innocence to the end.[47] If Carter had made a confession, it would have been a dramatic event and someone likely would have made a written record of it besides the court clerk.

A note on McSparran’s sermon manuscript, which Arnold said was written in a different hand, said the sermon was “delivered on Tower Hill April 14, 1751 before Thomas Carter, a criminal executed for murder, and to a numerous congregation,” but Arnold said the note might be incorrect because the text of the sermon suggests it was delivered shortly before the execution on May 10.[48]

This is a gibbet of the type that the body of Thomas Carter would have been placed in after he was hanged—as a terrible warning to others not to commit heinous crimes. This gibbet used in St Vallier near Quebec in 1763 for the body of Mdme. Dodier, hung for murder of her husband (New York Public Library)

The discrepancies go on and on. The official court record of the trial might have provided some undisputable information, but unfortunately it seems to be lost. The case is indexed at the state Judicial Records Center, but the case file is missing. The only remaining record is an entry in a logbook of executions. Under the heading “April 1751,” it briefly describes the two trials and the sentence. Of the defendant, it recorded that “the said Thomas not having the Fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the Instigation of the Devil . . . feloniously and voluntarily and of malice aforethought smote and wounded the said William Jackson” and that he “did violently and feloniously take and carry away [Jackson’s goods and chattels] to the great terror of the said William Jackson and against the Peace of our said Sovereign Lord the King his crown and dignity.”[49]

In all fairness, Updike, the Hazards, Stedman, and Cole were not writing academic treatises— Thomas R. Hazard’s book wasn’t called “Facts About Olden Times,” and Updike’s book wasn’t called “Facts About Dead Rhode Island Lawyers”— but it is difficult to avoid the feeling that nobody was going to let the facts get in the way of a good story.

We do know three things for sure: Jackson was murdered. Carter was hanged for it. And a dead gibbeted body swinging in the wind creates powerful memories.

The Carter-Killed-Jackson Monument, north of present-day Wakefield, across the street from the state office building. The granite pillar, erected in 1889 and inscribed on all sides, tells one version of the story (Karen Ellsworth)

[Banner Image: The Carter-Killed-Jackson Monument, north of present-day Wakefield, across the street from the state office building. The granite pillar, erected in 1889 and inscribed on all sides, tells one version of the story (Karen Ellsworth)]

Notes

[1] The New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, May 20, 1751, p. 2. [2] Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_Act_1751). [3] For more about the village of Tower Hill, see Esther Bernon Carpenter, South County Studies of Some 18th Century Persons, Places & Conditions in that Part of Rhode Island Called Narragansett (Boston, Mass.: The Merrymount Press, 1924), 156-158. [4] Carpenter, South County Studies, 238-239. [5] Wilkins Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar (Boston, Mass.: Thomas H. Webb & Co., 1842), 58-62. [6] James N. Arnold, ed. The Narragansett Historical Register, 9 vols. (Hamilton, R. I. and Providence, R. I.: The Narragansett Historical Publishing Co., 1882-1891), 1:215. [7] Caroline E. Robinson, The Hazard Family of Rhode Island, 1635-1904 (Boston, Mass.: The Merrymount Press, 1895), 121. [8] The Historic Marker Database (https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=29314). [9] Thomas R. Hazard, Recollections of Olden Times (Newport, R. I.: John P. Sanborn,1879), 23-25; Rowland G. Hazard, comp., The Jonny-Cake Papers of “Shepherd Tom” (Boston, Mass.: Merrymount Press, 1915), 179-180. [10] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 58-62. [11] Hazard, Recollections of Olden Times, 23-25. [12] Ibid. [13] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 58-62. [14] J. R. Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties, Rhode Island, 2 vols. (New York: W. W. Preston & Co., 1889), 1:76-79. [15] Rowland G. Hazard, comp., The Jonny-Cake Papers of “Shepherd Tom” (Boston, Mass.: Merrymount Press, 1915), 179-180. [16] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 58. [17] Ibid., 59. [18] Hazard, Recollections of Olden Times, 23. [19] Oliver H. Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane, 2 vols. (West Kingston, R. I.: Kingston Press, 1998), 1:24-26. [20] National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of Rhode Island, comp., Old Houses in the South County of Rhode Island (Boston, Mass.: The Merrymount Press, 1932), 23. [21] Kathleen Bossy and Mary Keane, Lost South Kingstown (Kingston, R. I.: The Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), 26-27. [22] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 58-59; Richard M. Lederer, Jr., Colonial American English (Essex, Conn.: Verbatim, 1985), 111. [23] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 60. [24] Hazard, Recollections of Olden Times, 23. [25] Hazard, The Jonny-Cake Papers, 180. [26] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 60. [27] Cole, History of Washington and Kent Counties, 1:78. [28] Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane, 1:25. [29] The New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, March 25, 1751, p. 2. [30] Joseph J. Smith, Civil and Military List of Rhode Island, 2 vols. (Providence R. I.: Preston and Rounds Co., 1900), 1:137, 1:143, 1:149. [31] Hazard, Recollections of Olden Times, 148-153. [32] Ibid., 24. [33] Ibid., 23; Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 59. [34] Colonial Dames, Old Houses in the South County, 23. [35] Daniel Allen Hearn, Legal Executions in New England: A Comprehensive Reference, 1623-1960 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1999), 139-140; Arnold, The Narragansett Historical Register, 1:215. [36] Susan Taryn McVicar, “The Last Gibbet Cage,” www.quahog.org (http://quahog.org/factsfolklore/index.php?id=211). For some unknown reason, McVicar calls the militia training field a “proving ground,” a 20th century expression. [37] Arnold, The Narragansett Historical Register, 1:291; 7:422. [38] The New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, March 25, 1751, p. 2. [39] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 61. [40] Thomas Durfee, “Gleanings from the Judicial History of Rhode Island,” Rhode Island Historical Tracts (Providence, R.I.: Sidney S. Rider, 1882), 1:18:20-21. [41] Arnold, The Narragansett Historical Register, 1:107-123. [42] The New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, May 20, 1751, p. 2. [43] Updike, Memoirs of the Rhode Island Bar, 62. [44] Carl R. Woodward, Plantation in Yankeeland (Chester, Conn.: The Pequot Press, 1971), 84-85. [45] Wilkins Updike, A History of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett, Rhode Island (2nd ed.), 3 vols. (Boston, Mass.: The Merrymount Press, 1907), 2:2:290. [46] Stedman, A Stroll Through Memory Lane, 1:25. [47] Carpenter, South County Studies, 158. [48] Arnold, The Narragansett Historical Register, 1:107. [49] Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, and General Goal Delivery, Kings County, Record Book A, April Term 1751, King v. Carter, p. 72-73 (Judicial Archives, Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, Pawtucket, R.I.).