Rhode Island can claim as its own Jemima Wilkinson, an important religious prophet and utopian leader in early America. Recently, she has been highlighted in college U.S. history text books as the first American-born woman to found a religious movement, and as an early strong female figure who led a group of devoted followers, including some powerful and wealthy men, in an age when almost all women were relegated to the household sphere.

Wilkinson was born into a Quaker family in Cumberland, Rhode Island, on November 29, 1752, the daughter of Amy Whipple and Jeremiah Wilkinson (a cousin of Governor Stephen Hopkins). Growing up on her father’s marginal farm in Cumberland, her mother would have a total of nine other children, until she died when Jemima was ten. Jemima had little formal education. She Iived during a time when religion was vitally important to ordinary persons and when many religious sects in Rhode Island vied for the attention of religious enthusiasts in rural areas. When Wilkinson was eighteen, she became caught up in the last wave of a religious revival known as the First Great Awakening, which emphasized the personal inner experience with God. When the popular English preacher, George Whitefield, visited Rhode Island in 1770, Wilkinson began attending evangelical “New Light” meetings outside the Quaker meeting, which resulted in her expulsion from the Quaker sect (also known as the Society of Friends).

On October 4, 1776, when she was twenty-four years old, Wilkinson fell extremely ill with typhoid fever. On the fifth day of the fever, she became unconscious and appeared to be close to death. When she awoke, Wilkinson declared that she had actually passed through the gates of heaven and had been raised from the dead. She announced that she had a new spirit within her, the “Publick Universal Friend,” and from that day on she used that name and would not answer to her birth name. Ezra Stiles, the former minister of a Congregational church in Newport and then the President of Yale University, succinctly described her transformation: “she died and is no more Jemima Wilkinson. But upon her restoration, which was sudden, the person of Jesus Christ came forth and now appears in her body with all the miraculous powers of the Messiah.”

Wilkinson began her career of preaching to “a lost and dying world.” Wilkinson once told Philadelphia Quaker James Emlen about her first experience preaching after her conversion. Emlen wrote: “She informed us that at her first call to Gospel service, she appeared in a meeting of our Society at Smithfield [the Smithfield Meetinghouse in Rhode Island], that after she had uttered a few words a Friend stood up and desired her to sit down, but she not submitting, the same request was repeated by another Friend, and then by another and another until no less than five Friends required her to desist, but she said as it was the Lord who spoke by her she could not be silent unless they applied their hands to her mouth.”

Wilkinson began to develop her beliefs. She dwelt much on the dread that religious seekers felt about their souls and the attainment of universal salvation. She shared much with the Quakers, including a philosophy based on loving-kindness to all. As did the Quakers, Wilkinson preached pacifism, which was not popular during the years of the Revolutionary War, and she supported peaceful relationships with Native Americans and equal rights for African Americans. Wilkinson’s religious services were similar to those of the Quakers: there was no music, no formal order of service, and worshippers waited in silence until felt called upon to speak.

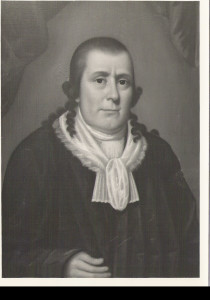

A portrait of Jemima Wilkinson after she had moved to upstate New York (Oliver House Museum, Penn Yan, NY)

Many of Wilkinson’s beliefs diverged markedly from the Quakers, including observation of the Sabbath on Saturday. Most importantly, the Publick Universal Friend practiced faith healing and dream interpretation. A few of her followers, disturbingly for her many detractors, believed that she was the female incarnation of God. She never declared herself a messiah, but she did little to discourage such discussion.

Like her contemporary, Ann Lee of the Shaker movement, she advocated celibacy, but she did not require it of her followers. She favored an equality of the sexes at a time when women had few legal rights in the United States.

In 1777, Wilkinson began to speak to crowds of Patriot soldiers in Rhode Island who gathered to try to recapture Newport from a British garrison. Sergeant William Russell of Craft’s Artillery Regiment of Boston, expecting shortly to be ordered to invade Aquidneck Island within the week, attended one of her sermons on October 8. Russell later wrote his wife, “This day Mrs. Jemima Wilkinson was at my quarters, and spoke with us, and exhorted us to repent, and turn to the Lord and he would have mercy upon us. It is the same woman that was at Boston and I like her much, and I beg of you to seek the Lord where he may be found, and pray for me, that God would cover my head in the day of battle, which I expect before this day week.”

That same year, the Universal Friend visited “poor and condemned prisoners in their chains,” probably deserters from the American army or local Tories caught supporting the cause of the Crown. In October 1778, Wilkinson received permission from Major General John Sullivan of the American army to travel to British-held Newport and then to England to preach there. After preaching some in Newport, for some reason she scrapped her plan to travel to England.

Wilkinson spoke in front of crowds in southern Rhode Island that included local elites, not just those on the lower end of the social scale. The fact that she was a woman preaching was a tremendous novelty at the time. She possessed a magnetic personality, which showed through in her powerful preaching. She was described at this time as being an attractive young woman, with a “fair complexion, florid cheeks, dark and very brilliant eyes, and beautiful white teeth.” On November 15, 1778, Daniel Updike, from a prominent North Kingstown planter family and the patriarch of Smith’s Castle, “went to the Hill to hear Miss Wilkinson preach who I liked very well.” Two days later, Updike went to the “Hill” again to hear her preach and described the crowd as a “gallery.” The “Hill” was probably Tower Hill or Little Rest Hill. “Nailer Tom” Hazard traveled to hear Wilkinson speak in or near Little Rest (now Kingston) on March 2, 1779. She made preaching trips to Providence, Newport, Tiverton, Little Compton, East Greenwich, and North and South Kingstown, as well as to Swansea and Dighton, Massachusetts.

In 1778, Wilkinson’s persuasive powers led to one of her most important converts, Judge William Potter, at the time one of the most influential men in southern Rhode Island. Potter, a fifty-seven year-old Narragansett planter, inherited a large landed estate from his father, John Potter, who was one of the wealthiest Narragansett planters in the colonial period. William Potter’s house and large farm were located about one mile north of Little Rest off North Road. Potter had a distinguished political career, serving several terms in the General Assembly and as chief justice of the King’s County Court of Common Pleas. In addition, he served for many years as a member of the South Kingstown Town Council and as Town Clerk. In 1750, Potter married Penelope Hazard, daughter of prominent Narragansett planter Thomas Hazard, in a service presided over by the Anglican minister, the Reverend James MacSparran. But in 1778, both William and Penelope, and several of their children, left the traditional Anglican church and became converts of Jemima Wilkinson.

Ezra Stiles wrote in his diary, “When I was at Narragansett Sept. 24, 1779, I heard much about Jemima who calls herself the Publick Universal Friend.” Stiles reported that Henry Marchant’s wife lodged with William Potter that day and spoke to Potter’s daughter, Alice. Stiles wrote that when praying, Alice “addresses the Public Friend whom she says is omnipresent, & calls her Messiah & herself her Prophet — she says Jemima is the son of God.” Stiles explained the Potter family’s unorthodox interest in Wilkinson was a response to a son who had become insane at age seventeen. (Stiles later conceded that Wilkinson herself did not claim that she was the offspring of God.)

In 1779, William Potter lost both his position as town clerk and his judgeship on the county court of common pleas. Potter’s loss of offices probably was the result of a reaction by townsmen against what they perceived to be his unorthodox religious leanings.

The Potters adopted Wilkinson’s view opposing slavery and distinctions based on skin color. The 1774 census indicated that William Potter had eleven blacks residing at his property, most of whom were likely slaves. After joining Wilkinson, Potter began to free his slaves. In the South Kingstown town records, for example, are two certificates of manumission, both dated March 27, 1780, when Potter freed two of his slaves, Pero and Caesar, with two members of the Universal Friend’s society serving as witnesses. Universal Friend records also show an unofficial manumission of Potter’s slave Mingo, and that several of the freed men joined the Universal Friends sect.

Judge Potter built a large addition of fourteen rooms to his house, which was called by locals “the Abbey.” This served as Wilkinson’s headquarters of operation for several years. The 1790 Rhode Island census indicates that fourteen white persons and thirteen free black persons resided on Potter’s estate. The adult blacks probably worked as paid farm workers and domestic servants on Potter’s land. Many of the black persons probably lived in outbuildings away from the Abbey. The white persons probably included Wilkinson and a few of her supporters, as well as Judge Potter, his wife Penelope, and some of their adult children.

Jemima Wilkinson created controversy in South Kingstown and the other towns to which she traveled in southern New England, and similar stories were told in these various towns. In 1780, in South Kingstown, she reportedly tried to raise from the dead the recently deceased twenty-two-year-old daughter of Judge Potter. Wilkinson reportedly blamed her failure on the lack of faith of the crowd.

On another occasion, Wilkinson claimed that she could duplicate Christ’s feat of walking on water. On the appointed day, with many spectators, she proceeded to Biscuit City Pond (some stories say it was Larkin’s Pond or other local ponds north of Little Rest), where she said she would perform the promised miracle. Upon reaching the water’s edge, she abandoned the attempt, explaining to the crowd that its lack of faith was the reason she had failed.

At this time, Jemima came to sense that the Millennium was imminent and would occur about the first of April 1780. Then on May 18, 1780, the sun was entirely blotted out from 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., a sign to many individuals of the imminent coming of Christ. Jemima received additional followers as a result of this event, which seemed to fulfill a portion of her prophecy.

A student from The Compass School stands on what is believed to be Inscription Rock or Preacher’s Rock, on top of which Jemima Wilkinson used to preach (Hilary Downs-Fortune)

In another instance, at the North Ferry in South Kingstown, north of Saunderstown, Wilkinson reportedly tried to bring a recently deceased disciple back to life. She said that he would rise from the dead on the third day. On the appointed day, she had the body brought out into the yard in order to show everyone the miracle. Some patriot soldiers were in the crowd, and their captain, who wanted proof that the man was indeed dead, requested permission to drive his sword through the body. After this request was made, the “corpse” sprang to life and ran into the house, dragging the sheet that had been laid on him in his coffin behind him. It is not known whether this story has any credibility.

Once, at a residence about a mile and a half west of East Greenwich village, while addressing a large assemblage of people, Wilkinson “stopped abruptly and declared that there was one within the hearing of her voice who would never see the light of another day.” The announcement created great alarm among her listeners. Later that night, a black man who worked in the household reportedly passed away.

One story about Wilkinson that circulated in South Kingstown was almost certainly a fabrication. It is repeated here to demonstrate the concern and jealousy that townspeople had about a woman who had assumed a position of such power. One day, Jemima Wilkinson was visiting Judge Potter, who was feeling poorly and in need of spiritual comfort. The Judge’s wife, who had been away when Jemima arrived at the house, came home unexpectedly and found Wilkinson in her husband’s bedchamber, in rather close proximity to the ailing jurist. Wilkinson said that it was all right for God’s lambs to love one another, because her religion believed in love. Mrs. Potter cut her off abruptly. “Minister to your lambs all you want,” the angry woman was supposed to have said, but in the future, please leave my old ram alone!” This story was circulated even though Wilkinson preached sexual abstinence and had attracted a following of women, as well as men. Indeed, Penelope Potter, the Judge’s wife, was even more devoted to Wilkinson than Judge Potter himself.

Wilkinson began to travel to towns in eastern Connecticut, where she attracted large crowds of people. On one occasion, at New London, “There were more than three thousand people at meeting who behaved very civil and gave very good attention.”

When traveling, Wilkinson rode a horse equipped with white leather straps and a blue velvet saddle, wore white or black flowing robes and a wide brimmed hat, and was accompanied by ten or so of her followers riding two-by-two behind her. She let her hair stream behind her and she intentionally wore androgynous clothing. Ezra Stiles complained that not only did Wilkinson preach blasphemy, but that she “dressed like a man.”

In 1782, accompanied by some of her followers, she rode her white horse into Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to preach, where she drew substantial audiences. While Wilkinson had much success in the city of brotherly love, she remained controversial. Several Philadelphia newspapers made especial effort to condemn, expose, and discredit her preaching, and at one event some in the crowd threw stones at her. She then withdrew to the more hospitable site of Worcester, Pennsylvania, where she increased her congregation of Universal Friends, including adding David Waggoner, a prominent Quaker.

By September 16, 1783, sufficient converts had joined with her that a “Declaration of Faith” was composed, and her followers became known as “The Society of Universal Friends.” Wilkinson strived to create a community based on equality, urging her members “not to strive against one another for mastery . . . .” Any of her follower’s dreams could be accepted as a revelation. She predicted the second coming of Christ. Her Society was dependent upon gifts from supporters, including wealthy supporters such as Judge Potter and James Parker. Unlike some religious sects that would follow her in later decades and centuries, Wilkinson held no property herself. All property was held in the name of the Society by a board of trustees.

Membership in Wilkinson’s following required acceptance of her authority, and she definitely wielded her authority. She warned her followers, “Ye cannot be my friends, except ye do whatsoever I command you.” One observer, David Hudson, stated that those who followed Wilkinson “dared not, on any occasion, disobey her commands. Jemima continued this practice, and almost uniformly enforced obedience, during the remainder of her life.”

In 1783, Wilkinson established a simple, one-story meetinghouse for her converts at Frenchtown in East Greenwich, on land donated by a follower, off what is now the South County Trail. She established another at New Milford, Connecticut.

Some of Wilkinson’s detractors state that she was forced out of Rhode Island and moved to upstate New York. She was obviously a source of controversy, a woman in a world dominated by men, yet having men under her sway. Even apart from discrimination based on her sex, the fact that she had formed a new unique religious sect made her a target. Many interpreted her claim of death and resurrection as a blasphemous attempt to duplicate the feat of Jesus Christ. Furthermore, some irate husbands, whose wives had followed Wilkinson’s advocacy of celibacy, added to the furor surrounding her.

Yet, the reality is that Wilkinson probably could have lived comfortably for the remainder of her life at the Abbey north of Little Rest. But instead, she sought to fulfill her dream of establishing a utopian colony of her own followers. In the early to mid-1780s, Wilkinson sent several members to explore upstate New York. In 1788, twenty-five members of her church, most from Rhode Island, founded a new town in the wilderness region of upstate New York, about one mile west of Seneca Lake. All of the settlers contributed to a joint fund for the purchase of about 14,040 acres in what are now the towns of Milo and Torrey. In March 1790, Wilkinson, the Potters and her other remaining followers departed Little Rest and moved to the new town in New York state, which upon their arrival contained 260 residents and was the largest town in the western part of the state.

Wilkinson wanted to develop a community far from persons outside her sect. She did not want any distinctions of wealth and foresaw a community whose residents owned land in common. But land speculators became interested in the town and the land deeds of some of her followers were questionable. In response, Wilkinson moved her sect even farther west in 1794, founding New Jerusalem (now Jerusalem), near what is now called Penn Yan, New York, in what is Yates County. (The name Penn Yan was adopted because most of its residents either hailed from Pennsylvania or were New England Yankees.)

In 1799, the Duke de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt published a travel account that contained a dozen pages describing his visit to New Jerusalem. He attended a religious meeting at Wilkinson’s house, which he found simple but “far from the cell of a nun.” The meeting, he said, was made up of about thirty men, women, and children. The Frenchmen wrote:

Jemima stood at the door of her bed-chamber on a carpet, with an arm-chair behind her. She had on a white morning gown, and waistcoat, such as men wear, and a petticoat of the same color. Her black hair was cut short, carefully combed, and divided behind into three ringlets; she wore a stock, and a white silk cravat, which was tied about her neck with affected negligence. In point of delivery, she preached with more ease than any other Quaker I have yet heard; but the subject matter of her discourse was an eternal repetition of the same topics of death, sin, and repentance. She is said to be about forty years of age, but she did not appear to be more than thirty. She is of middle stature, well made, of a florid countenance, and has fine teeth, and beautiful eyes. Her action is studied; she aims at simplicity, but there is something pedantic in her manner.

Judge Potter and James Parker grew apart from Wilkinson and eventually resigned from the sect in 1800. Before he resigned, Potter secured papers from many of the town’s settlers releasing all their lands to him, possibly because he had helped fund the original purchases of the land. In 1800, Potter sued Wilkinson in court for blasphemy, but lost when the judge noted that Potter must have been blasphemous as well since he had been a devoted follower. Potter sued Wilkinson again, this time for ejectment from the land. At trial Wilkinson won by producing a document with signatures from all of her followers that established that control of the lands stayed with her. Judge Potter left the courtroom in disgrace with a large bill of court costs to pay. Still, Judge Potter reportedly acquired about 16,000 acres of land in the Genesee country.

Potter’s house in New Jerusalem became the center of the town’s anti-Wilkinson feelings. James Emlen, in his diary, wrote of Judge Potter: “he apprehends himself now that she [Wilkinson] is entirely an imposter and that her settling this country was a mere trick of interest in order to secure a maintenance, she being in indigent circumstances and endeavoring to persuade her associates that it is unlawful for her to labor with her hands.”

Eventually Potter returned to his South Kingstown farm, leaving his wife Penelope behind. Penelope declared that she “meant to live and die a Friend.” But William found that townspeople still resented his behavior. Running short of money, he returned to New Jerusalem. Before he died in 1814, Potter and Wilkinson reportedly reconciled their differences. Elisha R. Potter, Sr. of Little Rest, Rhode Island, acquired the Abbey and its surrounding farm from William Potter’s son, but he did not preserve the mansion, elegant gardens, fruit orchard, and high fences, which quickly fell into ruins.

The grounds of the Abbey, known later as the Potter-Peckham Farm, is now the site of The Compass School at 537 Old North Road. Local tradition holds that Inscription Rock (or Preachers Rock) just north of the farm buildings was where Wilkinson often preached. It is about eight feet long, four feet wide and three feet high.

Wilkinson made her headquarters in an impressive five bay, two-and-one-half five-story Federal-style house, built about 1809 in Jerusalem, which still stands. She passed away on July 19, 1819 at age 68. She had “left time” as the Universal Friends put it.

The Society of Universal Friends did not long survive its charismatic founder. Her portrait, her Bible, sidesaddle, broad-brimmed hat, carriage, and many of her papers may be seen today at the Oliver House Museum in Penn Yan.

It is not easy to judge Jemima Wilkinson’s legacy. Her transformation into the Publick Universal Friend in 1776, and the powers of prophesy, revelation and healing she claimed afterwards for her new personality, are certainly controversial. Yet it seems overly harsh to call her a charlatan or crazy. The Reverend Ezra Stiles, the opposite of Wilkinson, in that he was a highly educated and worldly minister, claimed in a public lecture at Yale in 1781 that Wilkinson at the time of her acute illness in 1776 suffered from “temporary insanity or lunacy, or dementia . . . .” It is a reasonable explanation that Wilkinson was quite sincere in the belief that her body had become the “tabernacle,” as she called it, of the Holy Spirit. Her sincere belief in her conversion, in turn, led many Rhode Islanders at the time to convert and become her followers. This was a time when few persons had a worldly education based on rational principles and when instead many people sought to explain their world through religion. To castigate Wilkinson would be to also castigate other founders of new faiths, such as Ann Lee of the Shakers or Joseph Smith of the Mormons (more formerly known as the Church of the Latter Day Saints).

Wilkinson was a part of a tradition in Rhode Island of strong women who refused to be confined within prescribed limits. In the seventeenth century on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, strong women who suffered for their religious beliefs included Anne Hutchinson, who was banished for heresy from Massachusetts in 1637, and Mary Dyer, who was hanged for sedition by Puritans in Boston in 1660.

Wilkinson has the claim as the first American-born woman to found a religious movement. A contemporary who preceded her, Mother Ann Lee, considered the founder of the Shakers, was responsible for transplanting the religion from England to America in 1774. Lee, like Wilkinson, was elevated to the role of divine female messenger and posthumously was considered by some to have been a reincarnation of Christ. Following Wilkinson was Ellen Gould White, a co-founder of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, who reported on her visionary experiences in the mid-1800s and whose followers thought had the gift of prophesy. Some 100 years after Wilkinson’s death another woman succeeded in forming a religion based on the connection between the mind and the spirit and embraced a form of faith healing, Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science faith.

Wilkinson contributed to the free-thinking religious tradition in America that continues to this day. Western New York shortly after her death came to be known as the “burned-over district” from the number of religious revival movements that swept through in the first half of the 1800s. Joseph Smith led one of these movements, leading a group now known as the Mormons.

Wilkinson also helped start a tradition of female preaching, which became fairly widespread in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Her preaching on race relations contributed to the active role of women in some Protestant churches in the North pressing for the abolition of slavery in the South.

Wilkinson also deserves credit for being the primary force behind one of the first white settlements in western New York. Her drive to establish a utopian community outweighed her fears of settling in a wild country.

Wilkinson’s life certainly challenged the thinking of the overwhelming number of men and women of her day that the sexes each had their “separate spheres,” which divided the world into a masculine domain of public affairs and a feminine world of domestic concerns. Her challenge to this ideology was revolutionary even in an age of revolution and remains an impressive achievement.

Wilkinson has been the subject of a full-length, modern biography. She has an entries in Notable American Women 1607-1950 and in Remarkable Women of Rhode Island (written by smallstatebighistory.com authors Frank Grzyb and Russell DeSimone), and she has been studied in numerous history articles focusing on women or religion in early America. And, as stated, in recent years, she has appeared in some U.S. history college text books as an example of a strong woman who led both men and women.

[Banner Image: A young Jemima Wilkinson (Library of Congress)]Further Reading:

This piece is largely based on a chapter in Christian McBurney, A History of Kingston, 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County (Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), but it also has been updated and expanded.

For Wilkinson’s biography, see Herbert A. Wiseby, Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1964). See also Herbert A. Wisbey, Jr., “Wilkinson, Jemima,” Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, eds. Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, vol. 3 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), 609-10; Grzyb, Frank L. and Russell J. DeSimone, Remarkable Women of Rhode Island (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014); James A. Henretta, Elliot Brownlee, David Brody, Susan Ware, and Marilynn Johnson, America’s History, Third Edition, (Worth Publishers Inc., 1997).

For diary entries I located on Wilkinson during the Revolutionary War years, see Franklin B. Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York, NY: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 2:374, 380-82; 510-11; 3:289-90, 334; W. Russell to his Wife, Oct. 8, 1777, in “Orderly Book of the Regiment of Artillery Raised for the Defence of the Town of Boston in 1776,” Historical Collections of the Essex Institute 12:251-52 (Oct. 1876); Hazard, Caroline, ed., Nailer Tom’s Diary, Otherwise The Journal of Thomas B. Hazard of South Kingstown, Rhode Island 1778 to 1840 (Boston: Merrymount Press, 1930).

For more Rhode Island sources, see Wilkins Updike, A History of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett, Rhode Island, 2nd ed. (Boston: Merrymount Press, 1907); Greene, Daniel H., History of the Town of East Greenwich (Providence: J. A. & R. A. Reid, 1877); Charles E. Potter, Genealogies of the Potter Families and Their Descendants in America to the Present Generation, with Historical and Biographical Sketches (Salem, MA: Higginson Books Co., 1990; Thomas R. Hazard, The Jonny-Cake Papers of “Shepherd Tom” (Boston: Merrymount Press, 1915); J. Bruce Whyte, “The Publick Universal Friend,” Rhode Island History 26:18-24 (Jan. 1968) and 27:103-12 (Oct. 1968); Thaire Congdon Adamons, “They Left Rhode Island, Part Two, Followers of Jemima Wilkinson to Yates Co., N.Y.,” Rhode Island Genealogical Register 1:103-12 (Oct. 1978); South Kingstown Vital Records, Peace Dale, R.I., in first bound volume of South Kingstown Town Meeting Records on the reverse pages, William Potter manumits Pero and Caesar, 65 and 67 (March 1780).

See also Duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Travels Through the United States of North America, translated by H. Newman (London, 1800), 1:200; James Emlen Diary Entry, October 8 1794, in Bronner, Edwin B., “Quakers Labor with Jemima Wilkinson—1794,” Quaker History 58:1 (Spring 1969), 41-47; David Hudson, Memoir of Jemima Wilkinson (Geneva, NY, 1821), 33, 14, 231 (while the quote from Hudson rings true, much of Hudson’s biography is a scurrilous smear campaign against Wilkinson; Hudson was a high-minded Federalist Episcopalian); Abner Brownell, Dartmouth, Mass., Diary, 1779-1787, MS, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass, I, 29; Barbara E. Lacey, “Gender, Piety, and Secularization in Connecticut Religion, 1720-1775,” Journal of Social History 24:4, Summer, 1991), 799-821.