I never met John Gordon. According to Rhode Island court records, John Gordon was a convicted murderer, executed in 1845 for the brutal murder of Amasa Sprague, a wealthy industrialist. But I certainly heard a lot about John, starting in my grandmother’s lap in the 1930s. Granny Dooley used to lull me to sleep singing “The Old Spinning Wheel,” “Danny Boy,” and “Mother McCrea.” Occasionally she would mix in some folk songs, including one about “Poor Johnny Gordon.” I remember asking my mother about Johnny Gordon, and she said he was an Irishman who had been mistreated in Rhode Island.

I was about 10 when my sister Eileen told me the real story. John Gordon had been framed and executed for a murder he did not commit. Eileen never let me forget the Gordon story. She called me immediately after I had written a successful book with Red Auerbach, famed coach and president of the Boston Celtics. “Why are you writing books about sports when John Gordon lies in an unmarked grave as a convicted murderer for a crime he didn’t commit!” she demanded. This was the same sister fired for organizing servants into a union while working for a Newport society woman at 19. Unfortunately, Eileen died in 2002, eight years before I wrote the play “The Murder Trial of John Gordon.”

My Uncle Leo Kenneally gave me some good advice when I was about nine years old. “Ken, try to surround yourself with people who are more intelligent than you are.” It’s a rule I had no trouble following all my life. So when I decided to write a play about John Gordon, I sought out an old classmate from Providence College, Dr. Patrick T. Conley. The author of 39 books, Pat Conley has forgotten more about Rhode Island history than most of us will ever know. Like Mark Twain, Dr. Conley always combines sage advice with a touch of humor. Pat and I had lunch at the Fabre Line Club in Providence during the summer of 2009. In about two hours, I had most of the information I needed to write the play.

A few days after the meeting, Pat sent me an article written by one of his former students at Providence College, Dr. Scott Molloy. I had not met Scott at that point, but he is now a close friend. Scott’s article made a point that convinced me of John Gordon’s innocence. John Gordon was an alcoholic, subject to blackouts. He probably never would have been charged if he had been able to account for his whereabouts at the time of the murder. John was also a Catholic who never missed Sunday mass, regardless of how much he drank the previous evening.

Fr. John Brady heard John’s last confession just minutes before they walked to the scaffold together. In his final message, Fr. Brady said, “Have courage, John. You are going to join the noble band of martyrs of your countrymen who have suffered before at the shrine of bigotry and prejudice.” Scott Molloy asked two questions in his article: “Would Fr. Brady have made such a statement if John Gordon had just confessed to murdering Amasa Sprague? Would John Gordon have gone to his death without confessing the mortal sin of murder? With his last words, John Gordon forgave everyone involved in his conviction and execution.” His last words paraphrased those of Jesus on the cross: “I forgive them for they know not what they do.”

I began to write the play in the summer of 2008 while staying at my brother Bob’s summer home in Narragansett, Rhode Island. My brother Jack stayed was with me as I wrote the play. I can still see him standing in the doorway, waiting for the next page to be written. Sadly, Jack died a year before the play opened. However, with the input from my two historians, I put together the story that became the basis for my play.

On December 31, 1843, Amasa Sprague was shot and brutally bludgeoned to death. The gory incident touched off the Gordon murder trial, an event which became the Rhode Island version of the Sacco-Vanzetti case- but here, the defendants were Irish Catholic immigrants rather than Italians. Amasa Sprague was a powerful, wealthy, and influential man. He was administrator of the A & W Sprague industrial empire, a portion based in Cranston, Rhode Island. He personally supervised the Cranston complex at Sprague’s Village (near the present Cranston Print Works) in the manner of a feudal baron, with several hundred Irish men, women, and children in his employ.

Amasa had a strong and forceful personality. Sprague’s Village was his. He owned the plant, the company houses, the company store, and the farm which supplied that store. He even owned the church where the Protestant workers worshipped. William Sprague, Amasa’s brother, was the United States Senator from Rhode Island and former governor. He and his brother had a disdain for the recent immigrants called the “low Irish.” However, the brothers did not let their prejudice stand in the way of hiring Irish immigrants who toiled for meager wages in their textile mills.

On that fateful Sunday afternoon, December 31, 1843, 46-year-old Amasa left his mansion adjacent to his factory and began to walk northwest toward a large farm he owned in the neighboring town of Johnson, a mile-and-a-half distance, using a shortcut. Later that same day, Michael Costello, a handyman in the Sprague household, took the same route and came upon Sprague’s bloodied body. Sprague had been shot in the right forearm and then brutally beaten to death. The sixty dollars found in the victim’s pocket eliminated robbery as a motive, making the murder appear to be one of hatred or revenge.

Suspicion immediately centered on the Gordon family, a clan of Irish immigrants who were particularly hostile towards the strong-willed Yankee industrialist. The family’s earliest arrival, Nicholas Gordon, had emigrated from Ireland sometime in the mid-1830s, settled in Cranston, and opened a small store near Sprague’s Village, where he sold groceries, notions, and miscellaneous items. He then expanded his business by obtaining a license to sell liquor.

Liquor sales proved so popular in the dreary mill village that in 1843 Nicholas was able to finance the immigration of his family—mother, sister, three brothers (John, William, and Robert), and a niece—from Ireland to America. But Gordon’s liquor sales also produced a confrontation with Amasa Sprague, who felt the intoxicating brew was adversely affecting the productivity of his factory hands. Thus Sprague used his political weight in June 1843 to block a renewal of Nicholas Gordon’s liquor license.

Tempers flared and harsh words were exchanged between Nicholas Gordon and Amasa Sprague. “I’ll get you for this,” Gordon screamed at Sprague immediately after the verdict was announced. Because of this incident, Nicholas, William, and John Gordon were arrested the day after the murder. John and William were indicted for murder, and Nicholas was charged with being an accessory before the fact. Nicholas had been in Providence on the day of the murder, first at mass and later at a Christening at the time of the murder. The implication was that Nicholas planned the murder and imported his brothers from Ireland to carry it out.

John Gordon, an Irish immigrant, was the last man legally executed in the state of Rhode Island (although the verdict was highly questionable).

The trial of John and William was conducted in the spring of 1844 before a 12-man jury, none of them Irish Catholic. At the outset, William Gordon definitely established that he was elsewhere when the crime was committed. Attorney General Joseph M. Blake and Prosecutor William H. Potter zeroed in on the hapless 29-year old John Gordon, who could neither remember nor prove his whereabouts. The evidence was entirely circumstantial, starting with the fact that John’s shoe size matched the prints in the snow found at the murder scene. Witnesses identified a broken gun found at the location as the one Nicholas kept in his store.

A Providence prostitute swore she had seen John Gordon wearing the bloodstained coat found at the murder scene earlier on the day of the murder. The “blood” was later proven to be the madder dye used in coloring textiles. Nicholas admitted that he kept a gun in the store but claimed it disappeared shortly after the murder. He denied that the gun found at the scene was his. The missing weapon was the state’s most damaging evidence.

The Irish communities in Providence and Cranston rallied to the support of the Gordons and raised money for their defense. John P. Knowles, a Protestant attorney, agreed to defend the Gordons, a courageous decision that cost him his health and, later, his career.

The Gordons proclaimed their innocence, and Knowles defended them brilliantly. He was also able to establish that the real murderer was Big Peter, a huge Irishman who had been fired by Amasa Sprague three days before the murder. He disappeared on the day of the murder and was never found.

One of the state’s key witnesses, a known prostitute, Sally Field, claimed to be a close friend of William and John. She was the only person to connect John to the coat found at the murder scene. Knowles had Gordon try on the coat at trial, and it wrapped around him about three times, proving it belonged to a person much larger than the defendant. When Knowles asked Field to identify the two defendants, she became confused and pointed out John as William and William as John. The Providence Journal didn’t point out this mistake and failed to report any damaging testimony against prosecution witnesses throughout the trial. In fact, the day after the murder, a headline appeared in the Journal: “The Guilty persons, the Gordons, have been arrested for the murder of Amasa Sprague.”

This was not the first time that the Journal had taken a stand against Irish Catholics. When Irish Catholics campaigned to remove a restriction that required land ownership to become a qualified voter, the Journal’s publisher, Henry Anthony declared his unyielding opposition to such a change, even for naturalized Irish-Catholic soldiers who had fought in the Civil War to preserve the Union. The bigoted Anthony warned in the Providence Journal that if the restriction is removed, “Rhode Island will no longer be Rhode Island when this is done. It will become a province of Ireland. St. Patrick will take the place of Roger Williams, and the shamrock will supersede the Anchor and Hope.”

Anthony’s close friend, Chief Justice Job Durfee, who presided at the trial, gave a charge to the jury in which he called the killing the “most atrocious crime that had ever come to his attention.” Durfee also distinguished the testimony of native born witnesses and Gordon’s “countrymen,” implying that the latter Irish were less credible. The jury took Durfee’s advice, leaving the box at 6:30 p.m. on April 17 and returning one hour and fifteen minutes later with a verdict of guilty for John and freedom for William. When John was sentenced to death, he turned to his brother and said, “William, it was you who have hanged me.”

Two weeks before the execution, William Gordon went to John Knowles and admitted he had gone to the store after hearing about the murder and hidden Nicholas’ gun. Armed with the actual gun, Knowles appealed to the Rhode Island Supreme Court, but the Justices rejected it. Then Knowles petitioned the General Assembly for a reprieve and a commutation of sentence. The petition was rejected, but the narrowness of the margin indicated growing doubts concerning the fairness of the trial. Time was running out for John Gordon, and Governor James Fenner (he of the “Law and Order Party”) was not sympathetic to a stay of execution. When no reprieve was granted, John Gordon was hanged on February 14, 1845, in the state prison yard.

The funeral of John Gordon was attended by Irish from miles around, some journeying from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. According to observers, it took all day for the long procession to pass the home where John’s body had been taken. Nicholas Gordon was later freed after two juries deadlocked on the question of his guilt, but he never recovered from the personal calamity of his younger brother’s death or his confinement in the damp prison. Broken in health, he took to excessive drink and suffered premature death.

The execution of John Gordon had a permanent impact on Rhode Island law and politics, and it stands today as one of the darker episodes in its history. Seldom before or since has the cause of justice or the spirit of religious toleration implanted here by Roger Williams received such a severe jolt as it did on the day John Gorton was hanged. Numerous mass meetings were held in Providence to protest the continuance of capital punishment.

In 1852, just seven years after Gordon’s hanging, and in large part because of it, Rhode Island became the second state in the nation to abolish capital punishment. The General Assembly would later reinstate mandatory death penalty for persons who commit murder while incarcerated. No one was put to death under those policies, though, and in 1979 capital punishment was declared unconstitutional by the Rhode Island Supreme Court. John Gordon remains the last person executed by the State of Rhode Island.

I finished the play in 2010 and reached out to the drama department at Salve Regina University, owners of a wonderful historic theatre that would have been ideal for the play. I met with a young lady, the head of the drama department, who talked more about her degree in theater than she did about the play. I listened to her impressive background (all theory and little practical experience) and asked her a couple of questions about the play. When she couldn’t answer them, it was obvious that she hadn’t even read it. I picked up the manuscript and left.

My next approach was to the Trinity Playhouse in Providence. I received some favorable comments but no interest in producing the play. At the time, I read a story about Piyush (Pi) Patel, owner of the Park Theatre in Cranston. It was an old movie house that Pi invested millions in to produce a first-class theatre. The technology, seating, dressing rooms, and acoustics were on a level with any Broadway theater. I had a personal history with the Park Theatre, growing up about a block away on Hayward Street. Every Saturday and Sunday, I would go with my brothers to movies at the Park. Admission was 10 cents on Saturdays and 17 cents on Sundays.

I called Pi and received a call from Vivek Mistry, his assistant. Vivek read the play, had a positive impression, and set up a meeting with Pi. I do not think Pi ever read the play. But he liked the story and put his theatre and a considerable investment behind the play. I think Pi was also impressed that the Park Theatre was less than a mile from the spot where Amasa Sprague was murdered. It was an expensive play to produce, with 23 actors and expensive scenery and costumes. Pi never complained, even though he lost a considerable amount of money on the production.

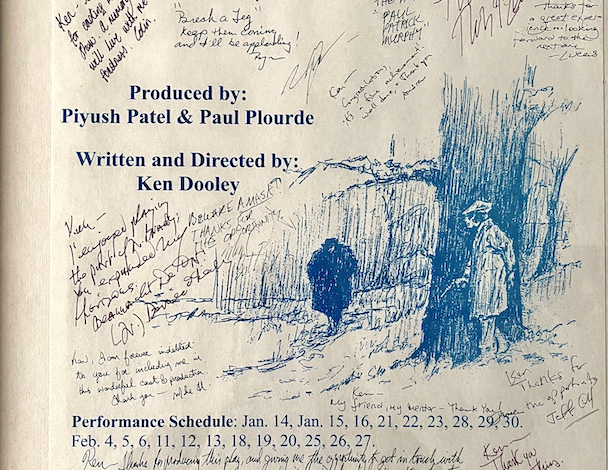

Playwright Ken Dooley’s playbill for his play, The Murder Trial of John Gordon, signed by the play’s actors and stage hands (Ken Dooley)

Someone once said that playwrights should never attempt to direct their own work. I began writing plays in the fourth grade at Eden Park Grammar School. Of course, I always directed and had the leading role. It’s a little different at the professional level. I started out as the director but quickly relinquished the role to Pamela Lambert, an African American actress, and director. Her husband, Jeff Gill, played defense attorney John Knowles and was magnificent. Jeff played the role of Red Auerbach in a later play I wrote and received the Massachusetts 2013 Best Actor Award.

We were fortunate enough to cast many good actors from Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Margaret Salvatore, a renowned costume designer, played a key role in the production. We even had a romance develop during the 23 performances. I attended the marriage of Chris Conte (William Sprague) and Tray Gearing (Sally Field) the following year. I treasure a comment Chris wrote on a Gordon poster I have framed in my office: “Thanks for changing my life.”

During one of the early performances, a man walked up to me and said, “You really think that John Gordon was innocent, don’t you?” It was State Representative Peter Martin. When I answered “yes,” he asked me what I planned to do about it.

“He was executed in 1845,” I replied. “It’s a little late for a reprieve.”

“It’s never too late for a pardon,” Martin said. Representative Martin suggested that he introduce a formal resolution in the Rhode Island House of Representatives that would request that Governor Chafee grant a pardon for John Gordon. A petition to support that request was signed by over 4,000 people who attended the play.

A House Resolution was submitted and referred to the House Judiciary Committee. The facts of the case were reviewed in a hearing on May 4, 2011. Testimony regarding the trial was provided by Rhode Island historians Patrick Conley, Scott Molloy, and Don Deignan; legal experts John Hardiman and Michael DiLauro from the Rhode Island Public Defender’s office; Director Pamela Lambert; and Playwright Ken Dooley. Many of the 23 actors who had appeared in the play attended the hearing.

The resolution to request the pardon was supported by the Committee on a 13 to 0 vote. On May 11, 2011, it was passed unanimously 70 to 0 by the full body of the House of Representatives and was transferred to the Rhode Island Senate for affirmation. On Wednesday, June 29, 2011, a ceremony was held at the Old State House in Providence, in the same room where John Gordon was tried and found guilty in 1844.

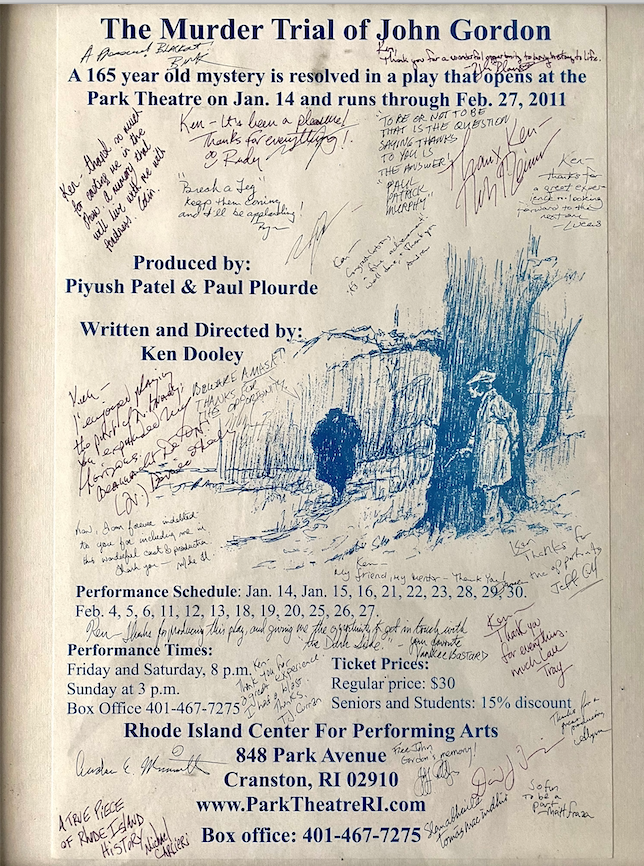

Poster for Ken Dooley’s 2011 play, The Murder Trial of John Gordon. During the play’s run in Cranston in 2011, attendees were invited to sign a petition urging the governor to pardon Gordon.

Governor Chaffee signed a gubernatorial proclamation granting Gordon a complete pardon. “John Gordon was put to death after a highly questionable judicial process and based on no concrete evidence,” the governor said. “There is no question he was not given a fair trial. Today we are trying to right that injustice. John Gordon’s wrongful execution was a major factor in Rhode Island’s abolition of and longstanding opposition to the death penalty,” Governor Chafee added.

“I sponsored this bill because I came to understand that an innocent man was forced to suffer the terror, despair, and humiliation of a public execution and that society and government will remain complicit if the record of the judgment of that travesty of Rhode Island history is not corrected,” Representative Martin said. “Today, we have righted a wrong, and we have done the just thing.”

The pardon of John Gordon attracted worldwide attention. The story appeared immediately in over 500 new sources, including publications in Ireland, England, Russia, and Turkey. In addition, there was a celebration at the St. Mary’s Cemetery in Pawtucket on Saturday, October 8, 2011. It was sponsored by the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, and Fr. Bernie O’Reilly, who played the part of the priest in the stage play, gave the homily.

The following day there was a dedication of a granite flagstone in memory of John Gordon at a ceremony at the Rhode Island Irish Famine Memorial. The inscription reads:

John Gordon. Born in Ireland. Died 2/14/1845 in Providence, RI. This stone placed in his honor by his fellow Irishmen and those who cared to right a wrong done unto him.”

“Forgiveness is the ultimate revenge.” October 8, 2011.

The last line is taken directly from my play. A song, “The Ballad of John Gordon,” was written and recorded by the Tom Lanigan Band. It was performed at the St. Mary’s Cemetery celebration. A medallion was designed and manufactured by Ed Johnson of Universal Plating, Inc., River Street, Providence.

The day after the pardon was issued, I went to my sister’s Eileen’s grave, dug a little hole, and planted the medallion. “You did it, kid,” I said. “Because of you, John Gordon is no longer considered a convicted murderer.”